People have been asking for a step-by-step guide for mitochondrial DNA, and here it is!

This article steps testers through all their results, page by page, including a dozen Discover reports, explaining what the information in each tool means. There’s SO MUCH great content provided, and you’ll want to absorb every tidbit.

This is meant to be a roadmap for you – a recipe card to follow to get the most out of your results.

You can either read through this article once, then sign on to your own account, or sign on now and follow along. Yes, this article is long, but it’s also a one-stop shop when you want information about any page or feature. Refer back to this article as needed, and feel free to forward it to others when they receive their results.

I’ve also provided additional resources for you at each step of the way, along with many tips and suggestions to help you help yourself.

I’m using the LeJeune sisters of Acadia as my example – in part because there were several questions about their heritage – including whether they were actually sisters, whether they were Native American, and if a third woman was also a sister.

Think about why you tested, and what you hope to learn so you know where to focus.

Everyone has their own motivation for testing, and we all want to extract as much information as possible. Some answers are genetic – thanks to mitochondrial, Y-DNA, and autosomal testing. Some answers are historical and genealogical. All of them need to mesh nicely together and confirm each other.

When they don’t, if they don’t, we need to understand how to discern the truth.

Every Ancestor Has a Mitochondrial DNA Story to Tell You

Sometimes it’s not our own results we’re analyzing, but the results of another tester – a cousin whose mitochondrial DNA represents a particular shared ancestor. We aren’t restricted to just our own mitochondrial DNA to decipher our ancestors’ stories.

What messages and secrets do those ancestors have to tell us? Our results read like the very best mystery novel ever – except it’s not a novel – it’s fact. And it’s ours!

Mitochondrial DNA is only passed from mothers to their children, never admixed or combined with the DNA of the father, so your mitochondrial DNA today is either exactly the same as that of your ancestors a few generations ago, or very close if a mutation has occurred between when they lived and today’s tester.

One of mitochondrial DNA’s strengths is that it can reach far back in time, it’s message undiluted and uninterrupted by recombination.

The messages from our ancestors are very clear. We just need to understand how to hear what they are telling us.

Step-by-Step Soup to Nuts

We will analyze the mitochondrial DNA results of multiple testers who descend from the LeJeune sisters, Edmee and Catherine, born in 1624 and 1633, respectively, to see what they have to tell their descendants. For a very long time, rumors abounded that their mother was Native American, so we will keep that in mind as we review all matching, Mitotree and mtDNA Discover tools provided by FamilyTreeDNA.

We will also learn how to evaluate seemingly conflicting information.

Soup to nuts – we will incorporate every sliver of information along the way and extract every morsel that can help you. Think of this article as your recipe and the reports and information as ingredients!

To be clear, you don’t HAVE to read all of this or decipher anything if you don’t want to. You can just glance at the matches and be on your way – but if you do – you’re leaving an incredible amount of useful information on the table, along with MANY hints that you can’t find elsewhere.

If there was an out-of-print book about this ancestral line in a rare book collection someplace, as a genealogist, you would drive half-way across the country to access that information. This is your rare book, that updates itself, and you don’t have to do anything other than take a mitochondrial DNA test, or find a cousin to take one for lines you don’t carry..

Come along and join the fun! Your ancestors are waiting!

The LeJeune Question

Recently, I wrote about my ancestor Catherine LeJeune, who was born about 1633, probably in France before her family settled in Acadia, present-day Nova Scotia.

The identity of her parents has been hotly contested and widely debated for a long time.

I intentionally did not address her DNA results in that article because I wanted to establish the historical facts about her life and address her mitochondrial DNA separately. The process we are following to analyze her DNA results is the same process everyone should follow, which is why we are taking this step-by-step approach, complete with detailed explanations.

Often, when people hit a brick wall with an ancestor, especially during European colonization of the Americas, someone suggests that the person surely “must be” Native American. Lack of records is interpreted to add layers of evidence, when, in fact, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

For example, for many of the earliest French Acadians, birth and baptism records have NOT been located in France, where massive record loss has been experienced.

Additionally, not all records that do exist have been indexed, transcribed, or digitized. Many are damaged and/or nearly impossible to read. Lack of records does NOT mean that those settlers weren’t French, or in this case, it does NOT indicate that they were Native American. It simply means we are lacking that piece of evidence.

Enter mitochondrial DNA.

This article is focused on how to use mitochondrial DNA to decode these messages from our ancestors. I’m providing a very short summary of the relevant historical factors about the LeJeune sisters so readers can keep this in mind as we review the 17+ tools waiting for us when mitochondrial DNA results are ready.

The First Acadian Settlers

The Acadians were French settlers in what is today Nova Scotia. The first Acadians arrived in LaHeve (LaHave), on the southern coast of Acadia, in 1632 after Acadia was returned to France from English control. There may or may not have been any French families in the original group, but if so, very few. In 1636, another group of settlers arrived, but no LeJeune is on the roster.

At the end of 1636, the fledgling Acadian colony was moved from LaHeve, on the southern coast, to Port Royal, a more protected environment.

While we don’t know exactly when the family of Catherine and Edmee LeJeune arrived, we can bracket the dates. We know that Catherine’s sister, Edmee LeJeune, born about 1624, married another settler, Francois Gautrot, about 1644 in Port Royal, so they had arrived by that time.

Edmee’s 1624 birth year is important for two reasons. First, there were no French settlers in the part of Acadia that became Nova Scotia in 1624, so that clearly demonstrates that Edmee was born in France.

It’s unlikely that Catherine was born in Acadia in 1633 given that the first known families arrived in 1636, and we have their names from the ship roster. Pierre Martin was on the 1636 ship, and Acadian history tells us that his son, Mathieu Martin, was the first French child born in Acadia, about 1636, based on the 1671 census.

We also know that there was an early Acadian man, Jean LeJeune, who was granted land at BelleIsle, near Port Royal, among other Acadian families, but he was deceased before the first Acadian census in 1671. Acadia was under English control again from 1654 to 1670, so Jean LeJeune’s land grant had to have occurred after 1636 and prior to 1654, and is where Catherine LeJeune is found as an adult.

Another source of confusion is that there is a third LeJeune woman, Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard, born about 1659. Her daughter, Catherine Joseph’s 1720 marriage record in Port Royal refers to her mother, Jeanne, as being “d’un nation sauvagé”, giving her parents’ names as Francois Joseph and Jeanne LeJeune “of the Indian Nation.” Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard lived with her first husband in Port Royal, but had relocated to LaHeve by 1708.

You can see why this led to confusion about LeJeune females.

Another male, Pierre LeJeune was associated with LaHeve, which suggests he may have been awarded land there, possibly before the colony moved to Port Royal. One of the reasons that the rumor that Catherine LeJeune had a Native mother is so persistent is the belief that Pierre came over early, as a laborer or soldier, and married a Native woman because there weren’t any European women available.

Pierre may well have arrived as a single man, but there is no shred of evidence to suggest Pierre is the father of the sisters, Catherine LeJeune and Edmee LeJeune. In fact, given that Jeanne was born about 1659, Pierre, if he was her father, may have been born as late as 1627, which makes it impossible for him to have been Catherine and Edmee’s father.

That speculation was before the advent of DNA testing, and before Stephen White discovered that there was also a Jean LeJeune who was awarded land exactly where Catherine is known to have been living a few years later.

While it would be nice to unravel this entire cat’s cradle of confusion, the questions we are seeking to answer definitively here are:

- Are Catherine LeJeune (born 1633) and Edmee LeJeune (born 1624) actually sisters?

- Is the mother of Catherine LeJeune and her sister, Edmee LeJeune, Native American or European?

- Is Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard, born about 1659, “d’un nation sauvagé” another sister of the LeJeune sisters?

- What else is revealed about the LeJeune sisters and their ancestors? Is there something else we should know?

I’ll provide a summary of the combined evidence after our step-by-step mitochondrial analysis.

Testing for Sisters

Mitochondrial DNA is passed from mothers to all of their children, but only females pass it on.

Since we have two LeJeune females, believed to be sisters, we need mitochondrial DNA from direct matrilineal testers for each woman. This is particularly important because we know unquestionably that Edmee was born in France in 1624, prior to Acadian settlement in New France, so her DNA should be European. If they match, it means that Catherine was born to the same mother who was not Native. If they don’t match, there’s a different message.

In some cases, a match might mean that they were born to females related on the matrilineal line, like first cousins, for example. But in the early days of Acadia, there were no European females other than the handful, less than a dozen, who arrived on the Saint-Jehan in 1636.

Fortunately, we have multiple testers for each woman in two DNA projects at FamilyTreeDNA, the only DNA testing company that provides mitochondrial DNA testing and matching. Testers can join special interest projects, and both the Mothers of Acadia Project, and the Acadian AmerIndian Project have testers who descend from the LeJeune sisters.

I’ve identified 28 descendants of Catherine, and 25 from Edmee, giving us a total of 53 known matrilineal descendants to work with. Not all are shown publicly, in projects. Catherine has a known total of 14 testers, and Edmee has 17 that are shown publicly. All testers are members of haplogroup U6a7a1a.

The fact that the descendants of these women match each other, often exactly, combined with Catholic parish register dispensations for their descendants, when taken together, prove conclusively that Catherine and Edmee were sisters, not paternal half-sisters.

Let’s look at each piece of evidence.

Mitochondrial DNA Results

When the lab finishes processing the mtFull test, the results are posted to the account of the test taker.

Click on any image to enlarge

You’ll see the Maternal Line Ancestry section which displays your mitochondrial mtDNA Results.

The three tabs we will be primarily working with are:

- mtDNA Matches

- Matches Maps

- Discover Haplogroup Reports, which includes another dozen+ reports and an updated Migration Map

- Advanced Matching

At the bottom right of your page, you’ll see two haplogroup badges.

The one at right is called the “Legacy” haplogroup, which means the haplogroup you were assigned prior to the release of the new Mitotree.

The Mitotree mtDNA Haplogroup, with the green “Beta” at the bottom, is the new Mitotree haplogroup, which I wrote about in a series of articles:

Your old Legacy haplogroup will never change, because it’s the 2016 version that was not updated by the previous tree-keepers. That’s why the FamilyTreeDNA R&D team, me included, developed and birthed the new Mitotree. There were thousands of new haplogroups that could be defined to kick-start our genealogy, so we did.

The mitochondrial tree went from about 5000 branches to over 40,000 in the new Mitotree, each providing additional information to testers.

Not everyone received a new haplogroup, but about 75% of testers did, and another new Mitotree version will be released soon. In order to receive a new haplogroup, testers needed to:

- Have at least one qualifying, stable mutation that had not been previously used to define a haplogroup

- Match at least one other person in the same haplogroup branch with the same mutation(s)

In the case of the LeJeune sisters, there were no mutations that met all of the qualifications, so their known descendants did not receive a new haplogroup. That’s fine, though, because it’s not the name but the messages held by the information that’s important – and there’s a LOT to work with.

Let’s start with matches.

Matches

Of course, the first thing everyone does is click to see their matches.

The default is Detail View, but I prefer Table View (top left) because you can see more matches on the same page.

Catherine’s descendant whose matches are shown here has 108 Full Sequence matches, which are labeled as the “Coding Region.” The Coding Regions is the mtFULL test and includes both the HVR1 and HVR2 regions. Viewing Coding Region matches means they have taken the mtFull test, which sequences all 16,569 locations of the mitochondria.

When you click on the “Coding Region”, you are seeing matches to people who took all three test levels, not just the first one or two.

There are three test levels to view:

- HVR1

- HVR1+HVR2 both

- Coding Region, which is in addition to the HVR1+HVR2 regions

You can no longer order three different test levels today, although at one time you could. As costs decreased, it no longer made sense to offer multiple testing levels, and often the HVR1 or HVR1+HVR2 results, which only tested about 500 locations each, would confuse people.

People at the lower HVR1 or HVR1+HVR2 levels, known as mtPlus, can upgrade to the complete mtFull level, and should.

However, because some people only tested at those lower levels, matches are still shown at three levels, with different match thresholds for each level.

Matches at the HVR1 or HVR1+HVR2 levels *might* be entirely irrelevant, reaching back thousands of years. They could also be much more current, and critical to your genealogy, so don’t assume. Just one unstable mutation can cause a mismatch though, and at lower levels, cause you not to match someone with the same ancestor, which is why the full sequence test is so critically important.

For some testers, matches at lower levels sometimes provide the ONLY match to your known ancestor. So don’t skip over them. If you find a critical match there, you can email the tester to see if they will upgrade to the mtFull test.

People who test only at the HVR1 or HVR1+HVR2 level receive a more refined haplogroup after they upgrade, so the haplogroups between the HVR1/HVR2 testers and the full sequence test won’t match exactly. For the LeJeune sisters, the haplogroup for HVR1/HVR2-only testers is U6a and for full sequence testers, it’s U6a7a1a.

While full sequence matches are wonderful, if you’re searching for a particular ancestor and the ONLY place they appear is the HVR1 or HVR1+HVR2 testing levels, you’ll want to pursue the match. You may also want to evaluate lower level matches if their ancestors are from a specific location – like France – even if their earliest known ancestor (EKA) is not your ancestor.

To view your HVR1 or HVR1+HVR2 matches, just click on either of those links. You’ll see ALL of the results, including everyone who took the full sequence test. In this case, that means that the 217 HVR1 (hypervariable region 1) results will include the 120 coding region (full sequence) tests. I’ve already looked through the full sequence matches, so that’s not what I want.

If you ONLY want to see testers who did NOT take the Full Sequence test, use the Filter option. Select Filter, then the features you seek.

Fortunately, the LeJeune sisters have lots of known descendants at the mtFull level to work with, so we will focus on their full sequence matches.

Your Focus

On the matches page, you’ll be immediately interested in two fields:

- Maternal Earliest Known Ancestor (EKA) – the direct matrilineal ancestor of your match – unless they got confused and entered someone else

- Their Tree

Viewing the first several matches only produced one match to someone whose earliest known ancestor (EKA) is listed as Catherine or Edmee LeJeune, but perhaps the next group will be more productive. Note that females’ EKAs, earliest known ancestors, are sometimes challenging, given surname changes. So unfamiliar EKAs could represent generational differences and sometimes offer other hints based on their information.

Shifting to the detail view for a minute, you’ll want to review the genetic distance, meaning whether you’re an exact match or not.

If you’re not an exact match, a genetic distance of “1 step” means that you match except for one mutation at a specific location.

If you have a genetic distance greater than 3, meaning 4 mutations or more, you won’t be shown as a match on this match list. However, you can still be a haplogroup match, which we’ll discuss in the Discover section.

Essentially, with more than 3 mutations difference, it’s unlikely (but not impossible) that your match is genealogically relevant – meaning you probably won’t be able to identify your most recent common ancestor (MRCA).

However, that doesn’t mean that haplogroup-only matches can’t provide important clues, and we will look under every rock!

A Slight Detour – Confirmation Bias

This is a good place to mention that both ancestors and their location (country) of origin are provided by (some) testers to the best of their ability and understanding.

This tester selected “United States Native American” as the location for their earliest known ancestor. We don’t know why they entered that information. It could be that:

- The tester did not understand that the maternal country of origin means the direct MATRILINEAL line, not just someplace on the maternal side

- Selina Sinott was Native on her father’s side, or any line OTHER than her direct matrilineal line.

- They relied on oral history or made a guess

- They found the information in someone else’s tree

- They found all of the LeJeune information confusing (because it is)

The tester has provided no tree, so we can’t do any sleuthing here, but an Ancestry search shows a woman by that name born in 1855 in Starksboro, VT to Louis Senott and Victoria Reya. A further search on Victoria leads me to Marie Lussier who leads me to Marguerite Michel who leads me to Marie Anne Lord (Lore, Laure), who lived in Acadia, whose ancestor is…drum roll…Catherine LeJeune. You get the idea.

Yes, you may need to extend other people’s trees.

The Point

However, and this is the point – if you’re looking for confirmation that the LeJeune sisters were Native American, this ONE tester who entered Native American for an unknown reason is NOT the confirmation you’re looking for. Don’t get sucked into confirmation bias, or into categorically believing what someone else entered without additional information.

You need haplogroup confirmation, but, in this case, you don’t have it. However, if you’re new to genetic genealogy, you don’t know that yet, so hold on. We’re still getting there. This is why we need to review all of the reports.

And trust me, I’m not being critical because there isn’t a single seasoned genealogist who has NOT fallen down the rathole of excited confirmation bias or accepting information without further analysis – me included. We all need to actively guard against it, all the time. Confirm and weigh all of the evidence we do have, and seek missing evidence.

Let’s go back to the match results.

Matches – Haplogroups and Haplotypes

Scrolling down the Table View, the next group of matches shows many more matches to descendants of both Catherine and Edmee LeJeune.

Next, you’ll notice that there’s a Mitotree haplogroup, U6a7a1a, AND an F number. In this case, they are both checked in blue, which means you share the exact same haplogroup with that tester, and the exact same haplotype cluster, which is the F number.

I wrote about haplotype clusters, here.

If NEITHER box is checked, you don’t share either the haplogroup nor the haplotype cluster.

You can match the haplogroup, but not the haplotype cluster, which means the haplogroup box will be checked, but the haplotype cluster will not. If you share the same haplotype cluster, you WILL share the same haplogroup, but the reverse is not true.

What is a Haplotype Cluster, and why do they matter?

Haplotype Clusters

We need to talk about exact matches and what they mean. Yes, I know it seems intuitive, but it isn’t.

There are three types of matches

- Matching and Genetic Distance on your Match List

- Haplotype matching

- Haplogroup matching

Without getting (too much) into the weeds, an Exact Match in the Genetic Distance column on your match list excludes locations 309 and 315 because they are too unstable to be considered reliable for matching. So, 309 and 315 are EXCLUDED from this type of matching. In other words, you may or may not match at either or both of those locations. They are ignored for matching on your match list.

Locations 309 and 315 are also EXCLUDED from haplogroup definitions.

A haplotype F cluster match indicates that everyone in that cluster is an exact match, taking into consideration EVERY mutation, INCLUDING 309 and 315.

|

309 and 315 |

Why |

| Matching and Genetic Distance |

Excluded |

Unstable, probably not genealogically relevant and may be deceptive, leading you down a rathole |

| Haplogroup Definition |

Excluded |

Too unstable for tree branching and definition |

| Haplotype F Clusters |

Included |

Might be genealogically useful, so everyone can evaluate the rathole for themselves |

Some people think that if they don’t match someone exactly, they can’t have the same ancestor as people who do match exactly, but that’s not true. “Mutations happen” whenever they darned well please. Downstream mutations in stable locations that match between two or more testers will form their own haplogroup branch.

The most distant matches are shown on the last match page, and as you can see below, some descendants of Catherine and Edmee LeJeune have a 1-step difference with our tester, meaning a genetic distance of one, or one mutation (disregarding 309 and 315). One match has a 2-step mutation.

The fact that their F numbers are not the same tells you that their mutations are different from each other, too. If two of those people also matched each other, their F# would be identical.

The mutations that do not (yet) form a haplogroup, and are included in your haplotype cluster, are called Private Variants, and you cannot see the private variants of other people. Clearly, you and anyone in your haplotype cluster share all of the same mutations, including Private Variants.

Evaluating Trees and EKAs

By reviewing the matches, their EKAs, and the trees for the matches of Catherine’s descendants, I was able to create a little mini-tree of sorts. Keep in mind that not everyone with an EKA has a tree, and certainly not everyone who uploaded a tree listed an EKA. So be sure to check both resources. Here’s how to add your EKA, and a one-minute video, here.

The good news is that if your match has a WikiTree link when you click on their tree icon, you know their tree actually reaches back to either Edmee or Catherine if that’s their ancestor, and you’re not dealing with a frustrating, truncated two or three-generation tree, or a private tree. You can add your WikiTree link at FamilyTreeDNA here, in addition to any other tree you’ve linked.

Takeaways from Matches

- You can identify your common ancestor with other testers. By viewing people’s trees and emailing other testers, you can often reconstruct the trees from the tester back through either Catherine or Edmee LeJeune.

- Your primary focus should be on the people in your haplotype cluster, but don’t neglect other clusters where you may find descendants of your ancestor.

- If you see a male EKA name, or something other than a female name in the EKA field, like a location, the tester was confused. Only females pass their mitochondrial DNA to their descendants.

- If you’re searching for an ancestor whose mitochondrial DNA you don’t carry, use projects and WikiTree to see if you can determine if someone has tested from that line. From viewing the project results, I already knew that the LeJeune sisters had several descendants who had tested.

- If you’re searching for your ancestor on your match list, and you don’t find them in the full sequence results, use the filter to view people who ONLY took the HVR1 and HVR1+HVR2 tests to see if the results you seek are there. They won’t be on your full sequence match list because they didn’t test at that level. Testers at the lower levels will only have a partial, estimated haplogroup – in this case, U6a.

- For Edmee and Catherine LeJeune, we have enough testers to ensure that we don’t have just one or two people with the same erroneous genealogy. If you do find someone in a project or at WikiTree claiming descent from the same ancestor, but with a different haplogroup, you’ll need to focus on additional research to verify each step for all testers.

Resources:

Matches Maps

The Matches Map is a great visual resource. That “picture is worth 1000 words” tidbit of wisdom definitely applies here.

Clicking on the Matches Maps displays the locations that your matches entered for their EKA.

In the upper left-hand corner, select “Full Sequence,” and only the full sequence matches will be displayed on the map. All full sequence testers also have HVR1/HVR2 results, so those results will be displayed under that selection, along with people who ONLY took the HVR1 or HVR1/HVR2 tests.

We know that the Acadians originally came from France, and their descendants were forcibly expelled from Nova Scotia in 1755. Families found themselves scattered to various locations along the eastern seaboard, culminating with settlements in Louisiana, Quebec, and in some cases, back in France, so this match distribution makes sense in that context.

Be sure to enlarge the map in case pins are on top of or obscuring each other.

Some people from other locations may be a match, too. Reviewing their information may assist with breaking down the next brick wall. Sometimes, additional analysis reveals that the tester providing the information was confused about what to complete, e.g., male names, and you should disregard that pin.

Takeaways from the Matches Map

- These results make sense for the LeJeune sisters. I would specifically look for testers with other French EKAs, just in case their information can provide a (desperately needed) clue as to where the LeJeune family was from in France.

- Reviewing other matches in unexpected locations may provide clues about where ancestors of your ancestor came from, or in this case, where descendants of the LeJeune sisters wound up – such as Marie Josephe Surette in Salem, Massachusetts, Catherine LeJeune’s great-granddaughter.

- Finding large clusters of pins in an unexpected location suggests a story waiting to be uncovered. My matrilineal ancestor was confirmed in church records in Wirbenz, Germany, in 1647 when she married, but the fact that almost all of my full sequence matches are in Scandinavia, clustered in Sweden and Norway, suggests an untold story, probably involving the 30 Years War in Germany that saw Swedish troop movement in the area where my ancestor lived.

- For my own mitochondrial DNA test, by viewing trees, EKAs, and other hints, including email addresses, I was able to identify at least a country for 30 of 36 full sequence matches and created my own Google map.

- You can often add to the locations by creating your own map and including everyone’s results.

Resources:

Mitochondrial DNA Part 4 – Techniques for Doubling Your Useful Matches

Mitochondrial DNA Myth – Mitochondrial DNA is not Useful because the Haplogroups are “Too Old”

Before we move to the Discover Reports, I’m going to dispel a myth about haplogroups, ages, genealogical usefulness, and most recent common ancestors known as MRCAs.

Let me start by saying this out loud. YES, MITOCHONDRIAL DNA IS USEFUL FOR GENEALOGY and NO, OLDER HAPLOGROUPS DO NOT PREVENT MITOCHONDRIAL DNA FROM BEING USEFUL.

Here’s why.

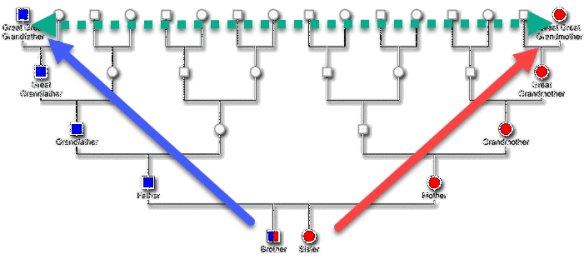

The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) is the person who is the closest common ancestor of any two people.

For example, the mitochondrial DNA MRCA of you and your sibling is your mother.

For your mother and her first cousin, the mitochondrial MRCA is their grandmother on the same side, assuming they both descend from a different daughter. Both daughters carry their mother’s undiluted mitochondrial DNA.

A common complaint about mitochondrial DNA is that “it’s not genealogically useful because the haplogroups are so old” – which is absolutely untrue.

Let’s unravel this a bit more.

The MRCA of a GROUP of people is the first common ancestor of EVERY person in the group with each other.

So, if you’re looking at your tree, the MRCA of you, your sibling, and your mother’s 1C in the example above is also your mother’s grandmother, because your mother’s grandmother is the first person in your tree that ALL of the people in the comparison group descend from.

Taking this even further back in time, your mother’s GGG-grandmother is the MRCA for these five people bolded, and maybe a lot more descendants, too.

At that distance in your tree, you may or may not know the name of the GGG-grandmother and you probably don’t know all of her descendants either.

Eventually, you will hit a genealogical brick wall, but the descendants of that unknown “grandmother” will still match. You have NOT hit a genetic brick wall.

A haplogroup name is assigned to the woman who had a mutation that forms a new haplogroup branch, and she is the MRCA of every person in that haplogroup and all descendant haplogroups.

However, and this is important, the MRCA of any two people, or a group of people may very well be downstream, in your tree, of that haplogroup mother.

As you can clearly see from our example, there are four different MRCAs, depending on who you are comparing with each other.

- Mom – MRCA of you and your sibling

- Grandmother – MRCA of you, your sibling, your mom and your mom’s 1C

- GGG-Grandmother – MRCA of all five bolded descendants

- Haplogroup formation – MRCA of ALL tested descendants, and all downstream haplogroups, many of whom are not pictured

Many of the testers may, and probably do, form haplotype clusters beneath this haplogroup.

When you are seeking a common ancestor, you really don’t care when everyone in that haplogroup was related, what you seek is the common ancestor between you and another person, or group of people.

If the haplogroup is formed more recently in time, it may define a specific lineage, and in that case, you will care because that haplogroup equates to a woman you can identify genealogically. For example, let’s say that one of Catherine LeJeune’s children formed a specific haplogroup. That would be important because it would be easy to assign testers with that haplogroup to their appropriate lineage. That may well be the case for the two people in haplogroup U6a7a1a2, but lack of a more recent haplogroup for the other testers does not hinder our analysis or reduce mitochondrial DNA’s benefits.

That said, the more people who test, the more possibilities for downstream haplogroup formation. Currently, haplogroup U6a7a1a has 34 unnamed lineages, just waiting for more testers.

Haplogroup ages are useful in a number of ways, but haplogroup usefulness is IN NO WAY DEPRICATED BY THEIR AGE. The haplogroup age is when every single person in that haplogroup shares a common ancestor. That might be useful to know, but it’s not a barrier to genealogy. Unfortunately, hearing that persistent myth causes people to become discouraged, give up and not even bother to test, which is clearly self-defeating behavior. You’ll never know what you don’t know, and you won’t know if you don’t test. That’s my mantra!

The LeJeune sisters provide a clear example.

OK, now on to Discover.

mtDNA Discover

Next, we are going to click through from the mtDNA Results and Tools area on your personal page to Discover Haplogroup Reports. These reports are chapters in your own personal book, handed down from your ancestors.

Discover is also a freely available public tool, but you’ll receive additional and personalized information by clicking through when you are signed into your page at FamilyTreeDNA. Only a subset is available publicly.

mtDNA Discover was released with the new Mitotree and provides fresh information weekly.

Think of Discover as a set of a dozen reports just for your results, with one more, Globetrekker, an interactive haplogroup map, coming soon.

Resources:

When you click through to Discover from your results, Discover defaults to your haplogroup. In this case, that’s U6a7a1a for the LeJeune sisters.

Let’s begin with the first report, Haplogroup Story.

Haplogroup Story

The Haplogroup Story is a landing page that summarizes information about your ancestor’s haplogroup relevant to understanding your ancestor’s history. Please take the time to actually READ the Discover reports, including the information buttons, not just skim them.

Think of Discover as your own personalized book about your ancestors – so you don’t want to miss a word.

You’ll see facts on the left, each one with a little “i” button. Click there or mouse over for more information about how that fact was determined.

When we’re talking about haplogroup U6a7a1a, it sounds impersonal, but we’re really talking about an actual person whose name, in this case, we will never know. We can determine the ancestor of some haplogroups that formed within a genealogical timeframe. The LeJeune ancestor in question is the person in whose generation the final mutation in a long string of mutations created the final “a” in haplogroup U6a7a1a.

Think of these as a long line of breadcrumbs. By following them backwards in time and determining when and where those breadcrumbs were dropped, meaning when and where the mutation occurred, we begin to understand the history of our ancestor – where she was, when, and which cultures and events shaped her life.

U6a7a1a was formed, meaning this ancestor was born, about 50 CE, so about 1950 years ago. This means that the ancestor of ANY ONE PERSON with this haplogroup could have lived anytime between the year 50 CE and the year of their mother’s birth.

This is VERY important, because there is an incredible amount of misunderstanding about haplogroup ages and what they mean to you.

The year 50 CE is the year that the common ancestor of EVERY PERSON in the haplogroup was born, NOT the year that the common ancestor of any two or more people was born.

By way of illustration, the LeJeune sisters were born in about 1624 and 1633, respectively, not 50 CE, and their most recent common ancestor (MRCA) is their mother, who would have been born between about 1590 and 1608, based on their birth years.

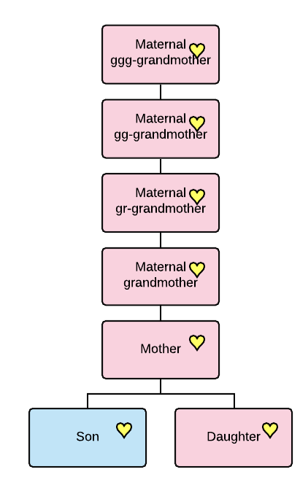

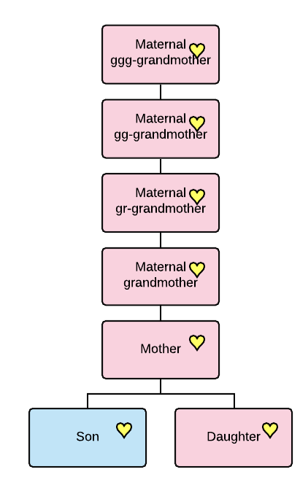

For reference, I’ve created this genealogical tree from individuals who took the mitochondrial DNA test and have identified their mitochondrial lineage on the LeJeune mother’s profile at Wikitree

You can see that both Edmee and Catherine have mitochondrial DNA testers through multiple daughters. I’ve color coded the MRCA individuals within each group, and of course their mother is the MRCA between any two people who each descend from Edmee and Catherine.

Mitochondrial DNA matches to the LeJeune sisters’ descendants could be related to each other anywhere from the current generation (parent/child) to when the haplogroup formed, about 50 CE.

You can easily see that all of these testers, even compared with their most distant relatives in the group, share a common ancestor born between 1590 and about 1608. Other people when compared within the group share MCRAs born about 1717 (blue), 1778 (peach), 1752 (green), 1684 (pink), 1658 (mustard), and 1633 (red).

Soooooo…a haplogroup born in 50 CE does NOT mean that you won’t be able to find any genealogical connection because your common ancestor with another tester was born more than 1900 years ago. It means that the common ancestor of EVERYONE who is a member of haplogroup U6a7a1a (and downstream haplogroups) was born about 50 CE.

The parent haplogroup of U6a7a1a is haplogroup U6a7a1, which was born about 1450 BCE, or about 3450 years ago.

In the graphic, I’ve shown other unknown genealogical lineages from U6a7a1 and also downstream haplogroups.

Haplogroup U6a7a1 is the MRCA, or most recent common ancestor of haplogroup U6a7a1a, and anyone who descends from haplogroup U6a7a1 or any of the 23 downstream lineages from U6a7a1, including 5 descendant haplogroups and 18 unnamed lineages.

The LeJeune haplogroup, U6a7a1a, has 35 descendant lineages. One downstream haplogroup has already been identified – U6a7a1a2 – which means two or more people share at least one common, stable, mutation, in addition to the mutations that form U6a7a1a. Thirty-four other lineages are as yet unnamed.

The fact that there are 34 unnamed lineages means that people with one or more private variants, or unique mutations, are candidates for a new branch to form when someone else tests and matches them, including those variants.

You’re a candidate for a new haplogroup in the future if no one else matches your haplotype cluster number, or, potentially, as the tree splits and branches upstream.

When a second person in a lineage tests, those two people will not only share a common haplotype cluster F#, they will share a new haplogroup too if their common mutation is not excluded because it’s unstable and therefore unreliable.

There are 127 members of haplogroup U6a7a1a today, and their EKAs are noted as being from France, Canada, the US, and other countries that we’ll view on other pages.

Haplogroup U6a7a1a has been assigned two Discover badges:

- Imperial Age – “an age noted for the formation and global impact of expansive empires in many parts of the world.” In other words, colonization, which is certainly true of the French who battled with the English to colonize New England, Acadia, and New France.

- mtFull Confirmed (for testers only)

Additionally, the LeJeune sisters have one Rare Notable Connection, and three Rare Ancient Connections, all of which may shed light on their history.

Takeaways from the Haplogroup Story

- The Haplogroup Story provides an overview of the haplogroup

- You can easily see how many testers fall into this haplogroup and where they have indicated as the origin of their matrilineal line.

- The haplogroup may have several new haplogroup seeds – 34 in this case – the number of unnamed lineages

- You can share this or other Discover pages with others by using the “share page” link in the upper right-hand corner.

- Don’t be discouraged by the age of the haplogroup, whether it’s recent or older.

Next, let’s look at Country Frequency.

Country Frequency

Country Frequency shows the locations where testers in haplogroup U6a7a1a indicate that their EKA, or earliest known matrilineal ancestor, is found. The Country Frequency information is NOT limited to just your matches, but all testers in haplogroup U6a7a1a, some of whom may not be on your match list. Remember, only people with 3 mutations difference, or fewer, are on your match list.

Haplogroup distribution around the world is very informative as to where your ancestors came from.

There are two tabs under Country Frequency, and I’d like to start with the second one – Table View.

Table View displays all of the user-provided country locations. Note that the Haplogroup Frequency is the percentage of total testers in which this haplogroup is found in this particular country. These frequencies are almost always quite small and are location-based, NOT haplogroup based.

There are now 40,000 haplogroups, and in haplogroup U, the LeJeune sisters are 6 branches down the tree with U6a7a1a.

In total, 127 testers are members of haplogroup U6a7a1a, and 42 of those claim that their ancestor is from France, which comprises 1% of the people who have taken the full sequence mitochondrial DNA test whose ancestor is from that location.

Let’s do the math so you can see how this is calculated and why it’s typically so small. For our example, let’s say that 8000 people in the database have said their matrilineal ancestor is from France. Of the 127 haplogroup U6a7a1a members, 42 say their ancestor is from France. Divide 42 by 8,000, which is 0.00525, and round to the nearest percentage – which is 1%.

The best aspect of this page is that you can see a nice summary of the locations where people indicate that their earliest known U6a7a1a ancestor was found.

Please note that the last entry, “Unknown Origins,” is the bucket that everyone who doesn’t provide a location falls into. That row is not a total but includes everyone who didn’t provide location information.

These location results make sense for the LeJeune sisters – maybe except for Ireland and Belgium. Some people don’t understand the directions, meaning that a matrilineal ancestor or direct maternal ancestor is NOT your literal “oldest” ancestor on your mother’s side of the tree who lived to be 105, but your mother-to-mother-to-mother-to-mother ancestor, so check to see if these people with unusual locations are in your match list and view their tree or reach out to them.

We don’t know why the person who selected Native American made that choice, but I’d bet it has to do with confusion about the “other” LeJeune female, Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard. Based on Catherine and her sister, Edmee LeJeune’s haplogroup through more than 50 testers, U6a7a1a, Native is incorrect.

Of course, that tester wouldn’t have known that if they completed their EKA information before they tested. Perhaps they entered information based on the stories they had heard, or flawed genealogy, and didn’t think to go back and correct it when their results were ready, indicating that Native was mistaken.

On the “Map View” tab, the locations are shown using a heat map, where the highest percentages are the darkest. Here, both France and Canada are the darkest because that’s the most common selection for this haplogroup with 1% each, while the rest of the countries registered with less <1%.

These colors are comparative to each other, meaning that there is no hard and fast line in the sand that says some percentage or greater is always red.

To summarize these two tables, because this is important:

- The Table View shows you how many people selected a specific country for their ancestor’s location, but the frequency is almost always very low because it’s based on the total number of testers in the entire database, comprised of all haplogroups, with ancestors from that country.

- The Map View shows you a heat map for how frequently a particular location was selected, as compared to other locations, for this haplogroup.

To view the difference between adjacent haplogroups, I always compare at least one haplogroup upstream. In this case, that’s the parent haplogroup, U6a7a1.

The Parent Haplogroup

If you look at haplogroup U6a7a1, just one haplogroup upstream, you’ll see that for Mauritania, the total number of U6a7a1 descendants tested is only “1”, but the haplogroup frequency in Mauritania is 10% which means that there are only 10 people who have been tested in the database altogether from Mauritania – and one person is haplogroup U6a7a1.

However, due to substantial under-sampling of the Mauritania population, the frequency for Mauritania, 10%, is higher than any other location.

Also, remember, these are user-reported ancestor locations, and we have no idea if or how these people determined that their ancestor is actually from Mauritania.

Please only enter actual known locations. For example, we don’t want haplogroup U6a7a1 members to look at this informatoin, then add Mauritania as their location because now they “know” that their ancestor is from Mauritania.

On the Map View, Mauritania is dark red because the percentage is so high – never mind that there are only 10 testers who report matrilineal ancestors from there, and only one was U6a7a1.

This map illustrates one reason why taking the full sequence test is important. Viewing partial haplogroups can be deceiving.

Catherine and Edmee LeJeune’s matrilineal descendants who only tested at the HVR1 or HVR1+HVR2 level receive a predicted haplogroup of U6a, born about 21,000 years ago. That’s because the full 16,569 locations of the mitochondria need to be tested in order to obtain a full haplogroup, as opposed to about 500 locations in the HVR1 and HVR1/2, each, respectively.

U6a – The Result for HVR1/HVR2-Only Testers

So, let’s look at what haplogroup U6a reveals, given that it’s what early LeJeune descendants who ordered the lower-level tests will see.

In the Table View for U6a, below, you see that the top 5 counties listed by haplogroup frequency are five North African countries.

A total of 801 people are assigned to haplogroup U6a, meaning the majority, 757, report their ancestors to be from someplace else. If two people from the Western Sahara (Sahrawi) comprise 67% of the people who tested, we know there are only three people who have tested and selected that location for their ancestors.

If you didn’t understand how the display works, you’d look at this report and see that the “top 5” countries are North African, and it would be easy to interpret this to mean that’s where Catherine and Edmee’s ancestors are from. That’s exactly how some people have interpreted their results.

Scrolling on down the Table View, 50 testers report France, and 10 report the US, respectively, with France showing a Haplogroup Frequency of 1% and the US <1%.

The balance of U6a testers’ ancestors are from a total of 57 other countries, plus another 366 who did not select a location. Not to mention that U6a was born 21,000 years ago, and a lot has happened between then and the 1620/1630s when Catherine and Edmee were born to a French mother.

The real “problem” of course is that haplogroup U6a is only a partial haplogroup.

The U6a map shows the highest frequency based on the number of testers per country, which is why it’s dark red, but the Table View reports that the actual number of U6a testers reporting any specific country. France has 50. Next is the US, also with 50, which often means people are brick-walled here. You can view the U6a table for yourself, here.

Why is this relevant for Catherine and Edmee LeJeune? It’s very easy to misinterpret the map, and for anyone viewing U6a results instead of U6a7a1a results, it’s potentially genealogically misleading.

Use Country Frequency with discretion and a full understanding of what you’re viewing, especially for partial haplogroups from HVR1/HVR2 results or autosomal results from any vendor.

If someone tells you that the LeJeune sisters are from someplace other than France, ask where they found the information. If they mention Africa, Morocco or Portugal, you’ll know precisely where they derived the information.

This information is also available on your Maternal Line Ancestry page, under “See More,” just beneath the Matches tab. Haplogroup Origins and Ancestral Origins present the same information in a different format.

Discover is a significant improvement over those reports, but you’ll still need to read carefully, understand the message, and digest the information.

Takeaways from Country Frequency

- Evaluate the results carefully and be sure to understand how the reports work.

- Use complete, not partial haplogroups when possible.

- The Haplogroup Frequency is the number of people assigned to this haplogroup divided by the entire number of people in the database who report that country location for their matrilineal ancestor. It is NOT the percentage of people in ONLY haplogroup U6a7a1a from a specific country.

- Table view shows the number of testers with this haplogroup, with the percentage calculated per the number of people who have tested in that country location.

- The Map shows the highest frequency based on the number of testers per country.

- Use the map in conjunction with the haplogroup age to better understand the context of the message.

Globetrekker, which has not yet been released, will help by tracking your ancestors’ paths from their genesis in Africa to where you initially find that lineage.

Before we move on to the Mitotree, let’s take a minute to understand genetic trees.

About Genetic Trees

The Mitotree is a genetic tree, also called a phylogenetic tree, that generally correlates relatively closely with a genealogical tree. The more testers in a particular haplogroup, the more accurate the tree.

FamilyTreeDNA provides this disclaimer information about the genetic tree. The Mitotree you see is a nice and neat published tree. The process of building the tree is somewhat like making sausage – messy. In this case, the more ingredients, the better the result.

The more people that test, the more genetic information is available to build and expand the tree, and the more accurate it becomes.

The recent Mitotree releases have moved the haplogroup “dates” for the LeJeune sisters from about 21,000 years ago for HVR1/HVR2 U6a testers to 50 CE for full sequence testers, and this may well be refined in future tree releases.

Mutations

Mutations and how to interpret them can be tricky – and this short section is meant to be general, not specific.

Sometimes mutations occur, then reverse themselves, forming a “back mutation”, which is usually counted as a branch defining a new haplogroup. If a back mutation happens repeatedly in the same haplogroup, like a drunken sailor staggering back and forth, that mutation is then omitted from haplogroup branch formation, but is still counted as a mismatch between two testers.

A heteroplasmy is the presence of two or more distinct results for a specific location in different mitochondria in our bodies. Heteroplasmy readings often “come and go” in results for different family members, because they are found at varying threshold levels in different family members, causing mismatches. Heteroplasmies are currently counted only if any person has 20% or greater of two different nucleotides. So, if you have a 19% heteroplasmy read for a particular location, and your sister has 21%, you will “not” have a heteroplasmic condition reported, but she will, and the location will be reported as a mismatch.

If you have a heteroplasmy and another family member does not, or vice versa, it’s counted as as a “mismatch,” meaning you and that family member will find yourselves in different haplotype clusters. Hetroplasmies do not presently define new tree branches. I wrote about heteroplasmies, here.

Takeaways from the Genetic Tree Disclaimer

- DNA is fluid, mutations happen, and all mutations are not created equal.

- Thankfully, you really don’t need to understand the nitty-gritty underpinnings of this because the scientists at FamilyTreeDNA have translated your results into reports and features that take all of this into consideration.

- Testing more people helps refine the tree, which fills in the genetic blanks, refining the dates, and expanding branches of the tree.

Resources:

Ok, now let’s look at the Time Tree

Time Tree

The Time Tree displays your haplogroup on the Mitotree timeline. In other words, it shows us how old the haplogroup is in relation to other haplogroups, and testers.

The Time Tree displays the country locations of the ancestors of testers who are members of that and descendant or nearby haplogroups. You can view the haplogroup U6a7a1a Time Tree, here, and follow along if you wish. Of course, keep in mind that the tree is a living, evolving entity and will change and evolve over time as updated tree versions are released.

Mousing over the little black profile image, which is the person in whom this haplogroup was born, pops up information about the haplogroup. Additionally, you’ll see black bars with a hashed line between them. This is the range of the haplogroup formation date. Additional details about the range can be found on the Scientific Details tab, which we’ll visit shortly.

On your Matches tab, remember that each match has both a haplogroup and a haplogroup cluster F# listed.

On the Time Tree, individual testers are shown at right, with their selected country of origin. In this case, you’ll see the person who selected “Native American” at the top, followed by France, Canada, the US, and other flags.

Haplogroup U6a7a1a includes several haplotype clusters, designated by the rounded red brackets. In this view, we can see several people who have haplotype cluster matches. Everyone has a haplotype assignment, but a haplotype cluster is not formed until two people match exactly.

In the Time Tree view, above, you can see two clusters with two members each, and the top of a third cluster at the bottom.

In case you’re wondering why some of the globes are offset a bit, they positionally reflect the birth era of the tester, rounded to the closest 25 years, if the birth year is provided under Account Settings. If not, the current tester position defaults to 1950.

Scrolling down to the next portion of the window shows that the third cluster is VERY large. Inside the cluster, we see Belgium, Canada, and France, but we aren’t even halfway through the cluster yet.

Continuing to scroll, we see the cluster number, F7753329, in the middle of the cluster, along with the French flag, two from Ireland, four from the US, and the beginning of the large unknown group.

In this fourth screenshot, at the bottom of the display, we see the balance of haplotype cluster #F7753329, along with eight more people who are not members of that haplotype cluster, nor any other haplotype cluster.

Finally, at the bottom, we find haplogroup U6a7a1a2, a descendant haplogroup of U6a7a1a. Are they descendants of the LeJeune sisters?

Looking back at our tester’s match list, the two people who belong to the new haplogroup U6a7a1a2 haven’t provided any genealogical information. No EKA or tree, unfortunately. The haplogroup formation date is estimated as about 1483, but the range extends from about 1244-1679 at the 95th percentile. In other words, these two people could be descendants of:

- Either Catherine or Edmee LeJeune, but not both, since all of their descendants would be in U6a7a1a2.

- An unknown sister to Catherine and Edmee.

- A descendant line of an ancestor upstream of Catherine and Edmee.

Takeaways from the Time Tree

- The visualization of the matches and haplotype clusters illustrates that the majority of the haplogroup members are in the same haplogroup cluster.

- Given that two women, sisters, are involved, we can infer that all of the mutations in this haplotype cluster were common to their mother as well.

- Haplotype cluster #F7753329 includes 19 testers from Catherine and 17 from Edmee.

- Downstream haplogroup U6a7a1a2 was born in a daughter of haplogroup U6a7a1a, as early as 1244 or as late as 1679. Genealogy information from the two testers could potentially tell us who the mutation arose in, and when.

- As more haplogroup U6a7a1a2 testers provide information, the better the information about the haplogroup will become, and the formation date can be further refined.

Smaller haplotype clusters have a story to tell too, but for those, we’ll move to the Match Time Tree.

Match Time Tree

The Match Time Tree is one of my favorite reports and displays your matches on the Time Tree. This feature is only available for testers, and you must be signed in to view your Match Time Tree.

By selecting “Share Mode”, the system obfuscates first names and photos so you can share without revealing the identity of your matches. I wrote about using “Share Mode” here. I have further blurred surnames for this article.

The Match Time Tree incorporates the tree view, with time, the names of your matches PLUS their EKA name and country, assuming they have entered that information. This is one of the reasons why the EKA information is so important.

This display is slightly different than the Time Tree, because it’s one of the features you only receive if you’ve taken the mtFull test and click through to Discover from your account.

The Time Tree view is the same for everyone, but the Match Time Tree is customized for each tester.

Your result is shown first, along with your haplotype cluster if you are a member of one.

You can easily see the names of the EKAs below the obfuscated testers’ names.

While we immediately know that descendants of both Catherine and Edmee are found in the large cluster #F7753329, we don’t yet know which ancestors are included in other haplotype clusters.

Haplogroup U6a7a1a includes two smaller haplotype clusters with 2 people each.

We know a few things about each of these clusters:

- The people in each cluster have mutations that separate them from everyone else except the other person in their cluster

- The results are identical matches to the other person in the cluster, including less reliable locations such as 309 and 315

- There are other locations that are excluded from haplogroup formation, but are included in matching, unlike 309 and 315.

- Given that they match only each other exactly, AND they did not form a new haplogroup, we know that their common unique mutation that causes them to match only each other exactly is unreliable or unstable, regardless of whether it’s 309, 315, a heteroplasmy, or another marker on the list of filtered or excluded variants.

Only the tester can see their own mutations. By inference, they know the mutations of the people in their haplotype cluster, because they match exactly.

If you’re a member of a cluster and you’re seeking to determine your common ancestor, you’ll want to analyze each cluster. I’ve provided two examples, below, one each for the red and purple clusters.

Red Haplotype Cluster #F3714849

Only one person in the red cluster has included their EKA, and the tree of the second person only reaches to three generations. Tracking that line backwards was not straightforward due to the 1755 expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia.

The second person listed their EKA as Edmee LeJeune, but they have a private tree at MyHeritage, so their matches can’t see anything. I wonder if they realize that their matches can’t view their tree.

We are left to wonder if both people descend from Edmee LeJeune, and more specifically, a common ancestor more recently – or if the unstable mutation that they share with each other is simply happenstance.

E-mailing these testers would be a good idea.

Purple Haplotype Cluster #F2149611

Evaluating the purple cluster reveals that the common ancestor is Catherine LeJeune. The question is twofold – how are these two people related downstream from Catherine, and how unstable is their common mutation or mutations.

Fortunately, both people have nice trees that track all the way back to Catherine.

Unfortunately, their MRCA is Francoise, the daughter of Catherine. I say unfortunately, because two additional testers also descend from Francoise, and they don’t have the haplotype cluster mutation. This tells us that the cluster mutation is unreliable and probably not genealogically relevant because it occurred in two of Francoise’s children’s lines independently, but not all four.

In other words, that specific mutation just happened to occur in those two people.

This is exactly why some mutations are not relied upon for haplogroup definition.

Takeaways from the Match Time Tree

- The time tree is a wonderful visualization tool that shows all of your matches, their EKAs and countries, if provided, in haplotype clusters, on the Time Tree. This makes it easy to see how closely people are related and groups them together.

- On your match page, you can easily click through to view your matches’ trees.

- You can use both haplotype clusters (sometimes reliable) and downstream haplogroups (reliable) to identify and define lineages on your family tree. For example, if a third person matches the two in haplogroup U6a7a1a2, the child haplogroup of U6a7a1a, and you could determine the common ancestor of any two of the three, you have a good idea of the genealogical placement of the third person as well.

- You know that if people form a haplotype cluster, but not a new haplogroup, that their common haplotype cluster-defining mutation is less reliable and may not be genealogically relevant.

- On the other hand, those less reliable mutations may not be reliable enough for haplogroup definition, but may be relevant to your genealogy and could possibly define lineage splits. Notice all my weasel words like “may,” “may not” and “possibly.” Also, remember our purple cluster example where we know that the mutation in question probably formed independently and is simply chance.

- I can’t unravel the ancestors of the red cluster – and if I were one of those two people, especially if I didn’t know who my ancestor was, I’d care a lot that the other person didn’t provide a useful tree. Don’t forget that you can always reach out via email, offer to collaborate, and ask nicely for information.

- We need EKAs, so please encourage your matches to enter their EKA, upload a tree or link to a MyHeritage tree, and enter a Wikitree ID in their FamilyTreeDNA profile, all of which help to identify common ancestors.

Resources:

Classic Tree

FamilyTreeDNA invented the Time Tree and Match Time Tree to display your results in a genealogically friendly way, but there is important information to be gleaned from other tree formats as well.

The Classic Tree presents the Mitotree, haplogroup and haplotype information in the more traditional format of viewing phylogenetic trees, combining their beneficial features. There’s a lot packed in here.

In this default view, all of the Display Options are enabled. We are viewing the LeJeune haplogroup, U6a7a1a, with additional information that lots of people miss.

The countries identified as the location of testers’ earliest known ancestors (EKA) are shown.

Listed just beneath the haplogroup name, five people are members of this haplogroup and are NOT in a haplotype cluster with anyone else, meaning they have unique mutations. When someone else tests and matches them, depending on their mutation(s), a new haplogroup may be formed. If they match exactly, then at least a new haplotype cluster will be formed.

Portions of three haplotype clusters are shown in this screenshot, designated by the F numbers in the little boxes.

Additional information is available by mousing over the images to the right of the haplogroup name.

Mousing over the badge explains the era in which the haplogroup was born. Rapid expansion was taking place, meaning that people were moving into new areas.

Mousing over the date explains that the scientists behind the Mitotree are 95% certain about the date range of the birth of this haplogroup, rounded to 50 CE. Remember, your common ancestor with ALL haplogroup members reaches back to this approximate date, but your common ancestor with any one, or a group, of testers is sometime between the haplogroup formation date, 50 CE, and the present day.

Mousing over the year shows the confidence level, and the date range at that level. These dates will probably be refined somewhat in the future.

If haplogroup members have private variants, it’s likely or at least possible that a new branch will split from this one as more people test

Mousing over the star displays the confidence level of the structure of this portion of the Mitotree based on what could be either confusing or conflicting mutations in the tree. For haplogroup U6a7a1a, there’s no question about the topology, because it has a 10 of 10 confidence rating. In other words, this branch is very stable and not going to fall off the tree.

Every haplogroup is defined by at least one mutation that is absent in upstream branches of the tree. Mutations are called variants, because they define how this sample, or branch, varies from the rest of the branches in the Mitotree.

These two mutations, A2672G and T11929C, are the haplogroup-defining mutations for U6a7a1a. Everyone in haplogroup U6a7a1a will have these two mutations in addition to all of the mutations that define directly upstream haplogroups (with extremely rare exceptions). Haplogroup-defining mutations are additive.

There may be more haplogroup-defining mutations than are displayed, so click on the little paper icons to copy to your clipboard.

You can view upstream haplogroups and downstream haplogroups, if there are any, by following the back arrows to upstream haplogroups, and lines to downstream haplogroups.

For example, I clicked on the arrow beside haplogroup U6a7a1a to view its parent haplogroup, U6a7a1, and a second time to view its parent, haplogroup U6a7a. If I click on the back arrow for U6a7a, I’ll continue to climb up the tree.

Beneath U6a7a, you can see the haplogroup branches, U6a7a1a and U6a7a2.

Beneath U6a7a1, you’ll notice:

- People who don’t share haplotype clusters with anyone

- Three haplotype clusters

- Five descendant haplogroups from U6a7a1, including the LeJeune sister’s haplogroup U6a7a1a.

To expand any haplogroup, just click on the “+”.

You may see icons that are unfamiliar. Mouse over the image or click on the “Show Legend” slider at upper right to reveal the decoder ring, I mean, legend.

You can read more about the symbols and how haplogroups are named, here, and see more about types of mutations in the Scientific Details section.

Takeaways from the Classic Tree

- The Classic Tree provides a quick summary that includes important aspects of a haplogroup, including when it was formed, which mutations caused it’s formation, and each branch’s confidence level.

- It’s easy to back your way up the tree to see where your ancestor’s founding haplogroups were located, which speaks to your ancestor’s history. Patterns, paths, and consistency are the key.

- Ancient DNA locations in your tree can provide a very specific location where a haplogroup was found at a given point in time, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that’s where the haplogroup was born, or that they are your ancestor. We will get to that shortly.

- You can share this page with others using the “Share Page” function at the top right.

Ancestral Path

The Ancestral Path is a stepping-stone chart where you can view essential information about each haplogroup in one row, including:

- Age and era

- Number of years between haplogroups

- Number of subclades

- Number of modern-day testers who belong to this haplogroup

- Number of Ancient Connections that belong to this haplogroup, including all downstream haplogroups

This “at a glance” history of your haplogroup is the “at a glance” history of your ancestors.

The number in the column titled “Immediate Descendants”, which is the number of descendant haplogroups, tells a story.

If you see a large, or “larger” number there, that indicates that several “child” haplogroups have been identified. Translated, this means that nothing universally terrible has occurred to wipe most of the line out, like a volcano erupting, or a famine or plague that would constitute a constraining bottleneck event. Your ancestors’ children survived and apparently thrived, creating many descendant downstream haplogroups, known as an expansion event.

If you see a smaller number, such as rows 5, 7, 8, 9, and 13, each of which have only two surviving branches, yours and another, several branches probably didn’t survive to the present day. This may reflect a bottleneck where only a few people survived or the lines became extinct over time, having no descendants today. Either that, or the right people haven’t yet tested. Perhaps they are living in a particularly undersampled region of the world, a tiny village someplace, or there aren’t many left.

The two most recent haplogroups have the most subclades, indicating that your ancestors were successfully reproducing in the not-too-distant past. Mutations occurred because they randomly do, creating new haplogroups, and several haplogroup members have tested today. Hopefully, genealogy can connect us further.

The next column, “Tested Modern Descendants,” tallies the total number of testers as it rolls up the tree. So, each haplogroup includes the testers in its downstream (child) haplogroups. The 127 people in haplogroup U6a7a1a include the two people in haplogroup U6a7a1a2, and the 226 people in haplogroup U6a7a1 include the 127 people in haplogroup U6a7a1a.

Looking at other types of trees and resources for each haplogroup can suggest where our ancestors were at that time, perhaps correlating with world or regional history that pertains to the lives of those ancestors.

In our case, the LeJeune sisters’ ancestors did well between 3450 years ago through the formation of U6a7a1a, about 1950 years ago. 3500 years ago, in Europe, settlements were being fortified, leadership was emerging as complex social patterns formed, and trade networks developed that spanned the continent and beyond.

Between 20,000 and 3,450 years ago, not so much. This correlates to the time when early European farmers were moving from Anatolia, bringing agriculture to Europe en masse. However, they were not the first people in Europe. Early modern humans arrived and lived in small groups about 50,000 years ago.

And they very nearly didn’t survive. Many lines perished.

Takeaways from the Ancestral Path

- The Ancestral Path shows the stepping stones back to Mitochondrial Eve, dropping hints along the way where expansions occurred, meaning that your ancestors were particularly successful, or conversely, where a bottleneck occurred and the lineage was in jeopardy of extinction.

- In some cases, where a lot of time has passed between haplogroups, such as 8,000 years between U and U6, we’re seeing the effect of lineages dying out. However, with each new tester, there’s the possibility of a previously undiscovered branch split being discovered. That’s precisely what happened with haplogroup L7.

Migration Map

The Discover Migration Map shows the path that your ancestor took out of Africa, and where your base ancestral haplogroup was formed.

Mousing over the little red circle displays the haplogroup, and the area where it originated. Based on this location where U6 was found some 31,000 years ago, we would expect to find U6 and subgroups scattered across North Africa, the Levant, and of course, parts of Eurasia and Europe.

It’s interesting that, based on what we know using multiple tools, it appears that haplogroup U initially crossed between the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, at the present-day Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb. Today, that crossing is about 15 nautical miles, but the sea level was much lower during earlier times in history, including the last glacial maximum. Humans would have seen land across the water, and could potentially have swum, drifted, or perhaps used early boats.

Over the next 10,000+ years, haplogroup U trekked across the Arabian peninsula into what is present-day Iran, probably moving slowly, generation by generation, then turning back westward, likely in a small group of hunter-gatherers, crossing the Nile Delta into North Africa, present-day Egypt.

They probably fished along the Nile. Food would have been plentiful along rivers and the sea.

It’s exciting to know that the ancestors of the LeJeune sisters lived right here, perhaps for millennia.

There’s more, however.

The Migration Map shows the location of the genetically closest Ancient DNA results to your haplogroup, obtained from archaeological excavations. This mapped information essentially anchors haplogroup branches in locations in both space and time.

Ancient DNA samples are represented by tiny brown trowels. Clicking on each trowel provides summary information about the associated sample(s) in that location.

Takeaways from the Migration Map

- Scientists have estimated the location where your base haplogroup originated. For the LeJeune sisters, that’s haplogroup U6 in North Africa along the Mediterranean Sea.

- The trowels show the locations of the genetically closest archaeological samples, aka Ancient Connections, in the FamilyTreeDNA data base.

- These Ancient Connections displayed on the map may change. New samples are added regularly, so your older samples, except for the oldest two, which remain in place for each tester, will roll off your list when genetically closer Ancient Connections become available.

- There are no Ancient Connections for the LeJeune sisters in France today, but keep in mind that Europe is closely connected. Today’s French border is only about 25 miles as the crow flies from Goyet, Belgium. France, sea to sea, is only about 500 miles across, and at its closest two points, less than 250 miles.

- Samples found at these locations span a large timeframe.

There’s a LOT more information to be found in the Ancient Connections.

Ancient Connections

Ancient Connections is one of my favorite Discover features. This information would never have been available, nor synthesized into a usable format, prior to the introduction of Mitotree and mtDNA Discover. Ancient Connections unite archaeology with genealogy.

- The first thing I need to say about Ancient Connections is that it’s unlikely that these individuals are YOUR direct ancestors. Unlikely does not mean impossible, but several factors, such as location and timeframe need to be considered.

- What is certain is that, based on their mitochondrial haplogroup, you SHARE a common ancestor at some point in time.

- Ancient samples can be degraded, with missing genetic location coverage. That means that not every mutation or variant may be able to be read.

- Different labs maintain different quality criteria, and location alignments may vary, at least somewhat, lab to lab. While this is always true, it’s particularly relevant when comparing ancient DNA results which are already degraded.

- Samples are dated by archaeologists using a variety of methodologies. FamilyTreeDNA relies on the dates and historical eras provided in the academic papers, but those dates may be a range, or contain errors.

- Obtaining information from ancient DNA samples isn’t as easy or straightforward as testing living people.

However, the resulting information is still VERY useful and incredibly interesting – filling in blanks with data that could never be discerned otherwise.

Many people mistakenly assume that these Ancient Connections are their ancestors, and most of the time, not only is that not the case, it’s also impossible. For example, a woman who lived in 1725 cannot be the ancestor of two sisters who were born in 1624 and 1633, respectively.

When you click on Ancient Connections, you see a maximum of about 30 Ancient Connections. Information about the genetically closest burial is displayed first, with the most distant last on the list.

Please note that the final two are the oldest and will (likely) never change, or “roll off” your list, unless an even older sample is discovered. When new samples become available and are genetically closer, the oldest other samples, other than the oldest two, do roll off to make space for the closer haplogroups and their corresponding samples.

Obviously, you’ll want to read every word about these burials, because nuggets are buried there. I strongly encourage you to read the associated papers, because these publications reveal snippets of the lives of your haplogroup ancestors and their descendants.

The small pedigree at right illustrates the relationship between the ancient sample and the haplogroup of the tester. Three things are listed:

- El Agujero 8, the name assigned by the authors of the paper that published the information about this ancient sample

- The haplogroup of the LeJeune descendant who tested

- The haplogroup of their common ancestor.

If no haplogroup is specifically stated for the ancient sample, the sample is the same haplogroup as the common shared ancestor (MRCA), meaning the tester and the ancient sample share the same haplogroup.

The Time Tree beneath the description shows the tester’s haplogroup, (or the haplogroup being queried), the ancient sample, and their common ancestral haplogroup.

Let’s analyze this first sample, El Agujero 8.