We don’t know where James Moore was born, but as a young man, we probably find James Moore in 1743 in Amelia County as an influx of settlers opened the land for cultivation. By about 1745, James had married a daughter of Joseph Rice, possibly Mary.

James’s married life was spent in the part of Amelia County that became Prince Edward County. He purchased land and in 1766, when his father-in-law died, James inherited 100 acres of the land where Joseph Rice lived and where James was already living, according to the will.

In 1767, James is noted on the tax list with the land he had purchased as well as his inherited land. In 1769, James Moore, along with James Moore Junior and Charles Henderson are listed together on the tax list. Shortly thereafter in 1769, James Moore and his wife, Mary, pulled up stakes, sold thier land and moved on to the next frontier.

By this time, James was about 50 years old, so no spring chicken. If he was going to move and keep all his children with him in the new location, it was time. To wait much longer would have meant that some of his children would marry and not accompany him to the new land. James packed everyone and everything they owned into a wagon and set off for untold adventures on a new frontier, 71 miles distant.

Halifax County, Virginia

By 1770, James Moore had moved to Halifax County, Virginia, along with a great number of other Prince Edward County families. Perhaps it was the death of his father-in-law that motivated the move. Maybe James felt he could sell his land in Prince Edward and purchase more land for the same amount of money in Halifax County. Or perhaps his wife wasn’t resistant to moving after her father died, although her (presumed) mother, Rachel was still living at that time.

Rachel is only mentioned one more time. On the 1767 tax list, she is listed with John Rice. After that, nothing, so she may have died about this time too.

It’s likely that James originally migrated from the Hanover County region to Amelia County – at least that’s where Joseph Rice and many of the families who settled in Amelia County originated.

The second half of his journey took him on to the area of present-day Vernon Hill in Halifax County

Land

The first thing James Moore did in Halifax County appears to have been to purchase land.

I created this table to attempt to track his land purchases and sales.

| Date |

From or To |

Cost |

Acres |

Acres Running total |

| 1770 |

From James Spradling, his grant |

100# |

238 |

238 |

| 1774 |

To Thomas Ward |

15# |

-25 |

213 |

| 1774 |

To Joseph Dodson |

60# |

-100 |

113 |

| 1778 |

To John Pankey |

|

-100 |

13 |

| 1780 |

To Charles Spradling |

30# |

-100 |

-87 |

| 1780 |

From James Henry by William Ryburn POA |

350# |

400 |

313 |

| 1781 |

To John Pankey |

2000# |

-30 |

283 |

| 1784 |

From James Henry (different books and witnesses – does not appear to be a duplicate) |

|

400 |

683 |

| 1786 |

To Leonard Baker |

10# |

-40 |

643 |

| 1786 |

Edmond Henderson |

|

-50 |

593 |

| 1787 |

William Hanes (Haynes) |

15# |

-30 |

563 |

| 1798 |

William Moore |

65# |

-200 |

363 |

Unfortunately, a reconciliation of the land purchased and sold by James Moore bears no resemblance to the tax lists of the era. The best I can figure is that someone else was paying the tax on some of the land.

To say that James’ land ownership is confusing is an understatement. Generally, when someone dies, their land is sold through probate, but apparently, not James. In 1798, James sells land to William, his son, and based on the transactions we have, James still owned 363 acres at that time.

In 1797, James disappeared from the personal tax lists, but his land remains. Did James leave at this point with his sons for East Tennessee? Did he tackle yet a third frontier at age 80?

There are two James Moores listed on the Grainger tax list in 1799, but our James would have been too old to be taxed, and his sons were not listed on that tax list.

Was his “last act” to sell land to his son, the Reverend William Moore, who had become somehow disabled?

James would have been roughly 80 years old. Did he die? If so, why was there no estate probated? He clearly still owned land, or, he transferred deeds that are not recorded.

Using the tax lists and not the land purchases/sales, James still owned between 120 and 50 acres of land. I can find no records of his land ever being sold. The deed was likely passed hand to hand and never registered until much later.

One thing we do know for sure, James was not on the qualified voter list of Halifax County in 1800, so he was assuredly dead or gone.

Tobacco is King

Why would James Moore have wanted so much land? It would have had to be cleared, a backbreaking prospect and he had to pay taxes on it whether it was cleared or not.

Virginia was a tobacco producing state. Tobacco depletes the nutrients in the soil quickly and new land has to be cleared for cultivation every 4 or 5 years, allowing the “old fields” to rest for two decades before they can be reused.

Brantley Henderson, born in 1884, a descendant of James Moore’s daughter Lydia, penned Only the Happy Memories, published in 1951. In the book, Brantley talks about tobacco farming in the 1880s and 1890s when he was young.

The methodologies hadn’t changed much in the 100 years since James Moore was cultivating his land on the second fork of Birches Creek.

As Brantley says, “There was always a lot of work to do.”

The hottest work I ever did was helping burn plantbeds. In those days, it would seem that farmers purposely did things the hard way. They literally cooked the plots of ground, usually about 50 by 50 feet, where tobacco plants were to be raised. The idea was that the fire would kill the seeds of both grass and weeds, but it took them a long time to learn that this didn’t happen.

A plot of ground with southern exposure was always selected. Across its highest end logs were stacked 6 feet high and 15 feet wide. Leaves, brush and lightwood knots were put under them and set afire. Two hours later the logs were pulled to uncooked ground. For moving them, we used poles 20 feet long which had iron hooks fastened to their ends. Always, it seemed, the wind blew the smoke, heat and sparks in our direction.

After the ground had been cooked, it was spaded, fertilized and raked. Then tobacco seeds were broadcast over its surface and the whole bed covered with cheesecloth. A few weeks later, our backs and arms grew weary from picking grass and weeds from around the tender tobacco plants.

Cultivation of Tobacco at James town, by Signed A.W. in lower left – Page 45 of A School History of the United States, from the Discovery of America to the Year 1878 (1878); from a digital scan from the Internet Archive, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31157197

The hardest job anyone had to do in the cultivation of tobacco was in planting it. The rows had previously been thrown up with turning plows and raked and pressed down with hoes into hills, 3 feet apart. After a soaking rain the backbreaking work began. Pa selected the plants and carefully put them in baskets. Blue Dick carried them from the beds to the fields. Colored girls walked along dropping the plants on the hills.

Using hand planters which were nothing more than lightwood knots with one of the ends trimmed to fit the palms of hands, and the other a sharp point, the drudgery began. The depths of the holes we made depended upon the size of the plants, for they had to be buried hear their buds. The stick was again plunged into the ground about an inch from the plants and the soil pressed gently against their roots. Our backs were bent from one end of the rows to the other.

Tobacco raising in those days was a never-ending job. After Christmas the cutting and log-rolling matches were held. The logs, brush and leaves were burned. Then the saplings and other underbrush were grubbed, thrown into piles and set afire. The ground was ready for the colter, but many of the roots were so thick the plow couldn’t break them and they had to be chopped with axes. Thousands of roots were removed this way and picked up with pitchforks or by hand and stacked and burned. Next came the turning plows which unearthed as many roots as had been destroyed before.

The tobacco curing barns were repaired, some received new roofs and others needed chinking and redaubing. The flues were removed and painted.

The stocks over which cut tobacco was thrown, or on which pulled leaves were strung to dry, had to be replenished. About 50 cords of wood with which tobacco was cured was cut, split and hauled to the barns.

By then it was early spring and time for burning the plantbeds.

The old land on which tobacco was to be planted was turned, dragged, furrowed, and fertilized, thrown into rows and the hills clapped. While waiting for a rain before planting, we might have had a few days rest, but Pa always found something else for us to do.

Two weeks after it was planted, the young tobacco was plowed and worked with hoes. Before one field was finished the others needed the same thing. About this time worms tried to eat it up. Some of the old ones were 4 inches long and as thick as a cigar. Those fellows could hunch their backs and spit tobacco juice as far and accurately as the farmers who sat around the stove in Gus Mitchell’s store in the wintertime. And they would bite, too. We had to sneak upon them and grab the backs of their heads to squash them.

Both sides of each leaf had to be examined for small worms and eggs.

Before sprays were invented it was a constant fight between men and worms, and many times the worms won the battle. By this time, we had topped the plants and the confounded suckers began shooting out. They more than doubled the work and the sun was getting hotter. It was then I always said, “Pa, I wish to goodness I could die before tobacco planting time and stay dead until it’s in the barns.”

We struggled along chopping grass and weeds from the stalks, “laying it by,” suckering and killing worms. When the bottom leaves began turning yellow, we dropped sticks between the rows on which the tobacco was to be thrown when cut, and then turned to suckering and killing worms again.

Harvesting the crops began in August. Several colored girls and I stood between the rows holding the sticks. Using hook-like knives which Pa made from old saws, the men split the stalks, ran their fingers down the slits, cut the stalks near the ground and threw them on the sticks. When enough was cut to fill a barn, we began hauling it in. With the loaded wagon standing in front of the barn’s door, something like a relay race began as the sticks were passed from man to man. Three men were up in the barn, one above the other, their legs spread wide apart between two tiers, over which the tobacco was hung. As the barn filled from the top, one by one the men came down.

Wood was piled in the fireboxes and the curing process began. For 2 or 3 days, or until the tobacco had turned yellow, the temperature was kept at about 110 degrees and then gradually stepped up. To dry the stalks and stems thoroughly, the heat was carried up to 220 degrees and this usually took one week. Then the doors were opened and brush was laid on the dirt floor, feely sprinkled with water to make the air humid, which caused the leaves to become supple that they might be handled without shattering them, while being removed to the packing house

Tobacco was traditionally packed into hogsheads which were very large barrels, about 48 inches long and about 30 inches across at the top, wider in the middle as they were rolled down the roads to the docks, and weighing about 1000 pounds each.

We know that hogsheads were still in use about 1900, as illustrated by this postcard.

Back to Brantley:

This job was repeated week after week until all of the tobacco was been taken from the fields and cured. Were we through with the stuff then? Not by a jugful.

If a heavy rain didn’t soften the tobacco, we had to haul it from the packing house to the ordering cellar put it on tiers again and sprinkle water on the red dirt floor. When it was “in order,” it was relayed to the sorting room above and stacked in piles.

One of us removed the stalks of tobacco from the sticks and laid them on the floor by the side of Pa, who sat in a chair in the middle of the room. He pulled the leaves from the stalks and sorted them according to quality. Usually there were from 6 to 8 grades. Bubba and a man tied the best leaves, and my job was to bundle the cheapest, which were called lugs.

Before the whole crop was harvested, cured and sold, it was Christmas again.

But we had fun around the tobacco barns during the curing seasons. Their roaring fires gave off comforting warmth to hands and feet when the fall nights were zippy and they lighted the road for play and, bless the Lord, it scared the hants (ghosts) away. Every boy in the community who could count on having a man walk home with him at bedtime was there for play and to eat watermelons, roasted corn and “sweet taters.” Bubba (Brantley’s brother) and I owned a white and liver-colored pointed dog. One of us would blindfold him and another boy would rub his breeches leg against the dogs nose, run down the road, climb a tree and yell. Fido was turned loose. He would pick up the boy’s trail and baying like a foxhound, follow the boy’s exact course and tree him. This type of fun sounds tame to a much older ear, but we youngsters found delight in the simple things of life in those far-off days.

And so it was. Life in the days of James Moore in Halifax County. I took the pictures of the following barns on or near James’ land when I visited, many of which may have dated to the time when James Moore lived.

Henderson Trail

What is now Henderson Trail in Halifax County was once James Moore’s land. Today, using Google Street View, we can see the historic structures on James’ land, some of which may well have been there when James lived.

Wouldn’t it be amazing if one of these actually WAS James’ barn?

Brantley’s recollections and these photos give us perspective about James life as a tobacco farmer, while the tax lists tell us about the land he owned, the number of horses, which were critical for farming, and the number of cows.

Unlike many plantation owners, James Moore never owned slaves, so the farm work would have fallen entirely to his family members and like-minded neighbors who may have helped each other with farm chores. The challenge, of course, was that everyone’s tobacco needed the same attention at the same time, so the only “spare hands” were perhaps laborers that could be hired from elsewhere.

Halifax Tax Lists

Most early Halifax tax lists no longer exist.

James is listed first in Halifax County on the 1782 tax list with 6 total white souls and 120 acres noted in the “alterations” (meaning changes from previous) category of the tax list.

This tells us that he has 4 children remaining at home. In 1782, James Moore would have been between 61 and 64 years of age. Several of his children would or should be married already and we know if fact that some were.

James Moore shows on the tax list in 1783 through 1787 with no acreage but in 1787 it looks like a James Jr. has 70 acres (but the Jr. could be Sr.) In 1788 James does have 120 acres, and in 1788 James Sr. is noted with 170 acres (or maybe the 7 is really a 2). In 1790 James is shown with 120 and has 120 every year until 1795 where it drops to 50.

James continues to show on the tax list through 1796, all years exempt beginning in 1788, and then he disappears from the personal tax list in 1797, but his 50 acres is still listed on the land tax list through 1814, after which it too is gone. In 1812 James Moore’s 50 acres is shown on Grassy Creek, so this may not be the right land or the right guy.

In 1806, a James Moore appears again on the personal tax list through 1822. This is not the same person as he is not exempt. This James is likely the son of William, would have been born in 1785 if he were 21 in 1806. He may have been living on and farming the land of James Sr. next to his father William.

Did “our” James Sr., father of Mackness Moore and Rice Moore move to Tennessee with Mackness and Rice in about 1797 or 1798? We know that son James Moore moved to Surry County, NC probably around 1770, but assuredly before 1791.

In 1783, a James Jr. appears with 30 acres but is not shown with land again. He is shown on the personal tax list in 1791, then from 1813-1829, then gone. It is unlikely that this is all the same person with all the gaps. However, we are safe to note that there is a James Jr. in 1783, so if this is James’ son, he would have been born in 1762 or before, meaning that his father would have to have been born in 1741 or before. We previously found James Jr. on the tax list with James Sr. in Prince Edward Co., in 1767, I’d guess that James Jr. is the eldest son.

Mackness Moore is listed as Mackerness in at least one year – and is on the tax list from 1788-1795. He is taxed with 100 acres of land in 1798 and owns it though 1800 even though he disappears from the personal tax list in 1794. His land is sold by 1800.

Rice Moore appears on the tax list in 1788 and eventually moved to the North part of the County where he is last taxed in 1792 before he leaves with his brother for Tennessee. He never owned land.

There is also a Thomas Moore on Birches Creek in 1783, 1792, 1798, 1799, 1800, 1811 and 1812. We have no more info on Thomas because he did not own land. I strongly suspect that the 1798-1800 Thomas is Thomas the father of orphans, Rawley and William. The 1783 and 1792 Thomas’s are indeterminate, but they could be a son of James or someone else entirely.

Let’s look at the Halifax County records involving James Moore.

James Moore in the Halifax Records

In 1770, James Moore purchased 238 acres from James Spradling on the second fork of Birches Creek, where the “said Moore now lives.” Witnesses George Brown (?), Sam Slate and George Stubblefield.

In 1773, James Moore filed suit against John Dalton, but the case was dismissed.

On March 11, of 1774, James Moore of Halifax sold land to Thomas Ward of Halifax County for 15#, 25 acres adjoining Thomas Ward, James Henry, Esq on the North side Thomas Ward’s plantation, meanders to the second fork of Burches Creek, signed James (M) Moore and witnesses James Thompson, Joseph Ferguson and Henry McDaniel. James’s wife Mary relinquishes dower. Recorded October 20, 1774

We know assuredly by 1774 that James Moore’s wife’s name was Mary. What we don’t know is whether or not Mary in 1774 was the same Mary Rice that was mentioned in Joseph’s Rice’s 1766 will, and if so, why he called his daughter by her birth name and not her married name.

On October 20th of the same year, James Moore and Mary, his wife, sold land to Joseph Dodson for 60#, one tract of about 100 acres bounded by the low grounds of the creek in James Spradling lines, James Henry, and the Tan Trough branch. Witness William Moore, James (O.) (is this a mark or an initial?) Moore Jr., Susannah (+) Moore, signed James (M) Moore and Mary (+) Moore. Mary Moore relinquished her dower.

The Ward and Dodson deeds were registered the same day. It was a long way to the courthouse. James and crew probably made that journey on court day, which was the best public entertainment to be had.

According to Brantley Henderson, “country people would crowd the courthouse grounds on “Courthouse Day,” where horse traders would try to swap worthless plugs to unsuspecting farmers for their good old nags and $100 to boot.”

In 1774, James Moore served as a witness in the suit Hancock vs Spradling where John Hancock was an assignee of James Spradling and paid James Moore 125# in tobacco for being a witness. This was typical and ordered by the court.

In 1776, James Moore witnessed a deed that I found quite interesting

James Henry of Accomack County to James Spradling of Halifax for and in consideration of the rents and covenants to be performed grants Spradling one certain tract of land in Halifax on the 2nd fork of Burches Creek bounded by a corner of James Moor’s plantation where he now lives, a corner of the said Henry’s order of Council land which he purchased of Col. Thomas Parremore of Accomack County near the road that leads from the said Henry’s Mill on the Sandy Creek to Fontaines Old Houses. To have and hold for the term of 21 years paying annual rent of the quitrent for the 1st 7 years, 30 shillings per years for the next 7 years, and for the last 7 years, the yearly rent of 3 # and the quitrents for the whole term. Spradling agrees to build a good, square, log dwelling house, shingled with heart of pine shingles put in with nails, the house to be 20′ by 16′ with a good plank floor overhead and barn 30′ by 20′ built in the same manner, to plant and raise 200 apple trees of good grafted fruit and 500 peach trees within the 1st 7 years and to leave the plantation in good tenantable repair at the expiration of the term. If the rent is ever behind and unpaid for 6 months, and no distress to be had on the premises, it shall he lawful for Henry to enter upon the premises and this lease to cease and be void for the future. Signed William Ryburn for James Henry. Witness Samuel Slate, John (mark I with top middle and bottom cross) Spradling, Chas (+) Spradling. Recorded November 21, 1776

The building that Spradling is supposed to build is probably very characteristic of the homes of the settlers of that era. 20 x 16. The size of my living room and an entire, large, family would have lived in that “good, square, log dwelling house” with its pine shingles put in with nails.

Even more ironic, the barn was almost twice as wide as the house.

Apple and peach trees. Entire orchards to be planted. I wonder if any are left today.

Spradling would have vacated this land in 1797 according to these terms.

Of course, the Revolutionary War was beginning about this time, and in the pension application file of one James Spradling, born in 1750, who enlisted in February 1776 for 3 years, we find that Mackness Moore gave testimony that he knew James in Virginia and that James Spradling lived with his father for two years prior to enlisting. Therefore, James Spradling would have lived in the James Moore household in 1774 and 1775. James Spradling eventually moved to Claiborne County, Tennessee, in close proximity to Mackness and Rice Moore and other members of the Moore family.

Why was James Spradling living with James Moore? Did James Moore simply need an additional farm hand, or was there more? Were they related? Is this James Spradling the son of the James Spradling that James Moore bought land from in 1770? James Moore knew the Spradlings in Prince Edward County.

In 1778, James Moore of Halifax sold to John Pankey of Halifax 100 acres on both sides of the branches of Birches Creek, mouth of the Tantroff Branch, Col. Hanries line, Barbery Branch. Signed James (M his mark) Moore, Witneses Joseph Dodson, Charles (C) Spradling, Edward (8) Henderson, William More. Recorded November 19, 1778. Mary the wife of said James Moore voluntarily relinquished her right of dower.

Mary apparently died between 1778 and 1781, given that she does not relinquish dower in 1781 or on land sales thereafter.

In 1780, James Henry of King and Queen County sells to James Moore of Halifax for 350# about 400 acres on one fork of Birches Creek, crossing the creek and bounded by a branch inside Henry’s order line. Signed William Ryburn for James Henry. Witnesses James (+) Moore Jr., William Moore, Edward (+) Henderson. Recorded October 19, 1780

Also in 1780, James Moore with his M mark witnesses the sale of 13 acres of land from Charles Spradling to John Pankey on the north side of Birches Creek. William Moore and Edward Henderson (+) were also witnesses.

In 1781, James Moore sold to John Pankey for 2000# about 30 acres on the second fork of Birches creek. Signed James (M) More – witnesses William Parker, Charles Crenshaw, Jonathan Colquitt. Recorded September 20, 1781

James also witnessed the land sale from Stephen Pankey to William Walton for 100 acres on the second fork of Birches Creek, along with John Pankey and Jonathan Colquit.

In 1782, James had 6 white and no black souls and paid one tithe.

1783 provides us with our first road hands list.

John Pankey surveyor from Walton’s Mill path to the county line, tithes John Sloane?, James Ferguson, Hugh Ferguson, Thomas Jeffress, Lewis Halay, Benjamin Halay, Daniel Trammell, Thomas Trammell, Richard Lamkin, Richard Thompson, William Yates, Jesse Spradling, Isaac Farguson, John Farguson, Nimrod Farguson, Charles Spradling, Mack (Mackness) Moore, Rich (probably Rice) Moore, William Moore, Thomas Williamson Jr and Sr, Edward Henderson, William Pankey, Nathan Sullins, John Mullins, William Ashlock, James Moore, Bartholomew Harris, Benjamin Edwards, William Edwards, Thomas Dodson Jr. and Sr., George Dodson, Robert, Mathis, John Tolles, Martin Palmer and William Walton.

Every property owner was required by law to contribute one day per year for road upkeep. The roads at that time, according again to Brantley Henderson, were “old, winding muddy roads.” While the farmers did travel in their wagons to the tobacco warehouses, they did not journey far beyond the neighborhood, to the point that Brantley had never journeyed the 15 miles to Vernon Hills to visit the old Henderson lands, cousins or cemeteries. “Only urgent business would take one so far from home.”

Brantley wrote of the roads, “With few exceptions, the tobacco wagons were drawn by 4 horses – an even dozen were really needed. What could rightly be called a road wasn’t in existence. The word “trail” would do honor to their memory. Little effort was made to grade and drain them and there were no bridges over the swamps and creeks. In fact, few of the rivers were bridged. The larger ones were crossed by ferry.

The one day required yearly road maintenance was “confined to the worst mudholes in each area. If possible, with picks, hand shovels and plows, ditches were dug to drain off water, then the holes were filled with loose dirt. Until a dry spell came to bake the dirt, the mudhole was worse than before.”

The 1783 tax list also tells us that James Moore owned 3 horses, 8 cows and was living beside William Moore.

In 1784, James Henry of King and Queen County sold to James Moore (with William Ryburn power of attorney) 400 acres on Birches Creek, John Pankey’s line, Nathan Sullins. Witnesses John Poindexter, Howard Henderson, William Walter.

In 1786, James Moore’s son, Rice Moore married Elizabeth Madison whose father was Roger Madison.

On the 1786 tax list, James Moore has 2 horses and 8 cows.

In 1786, James Moore sells to Edward Henderson about 50 acres on the second fork of Birches Creek bounded by Old Fields Branch, lines of James Henry, William Mors, and Nathan Sullings, witnesses Mackness Moore, William More and John Poindexter – James More signs with (M) mark. Deed dated July 13, 1786 and recorded October 19, 1786

Edward Henderson married James Moore’s daughter, Lydia. This land began the Henderson family legacy in Halifax County which remains today.

In 1786, James Moore sold 40 acres on Birches Creek to Leonard Baker.

James was also appointed surveyor of the road from the Double Branch to the Pittsylvania County line.

In the suit, Wimbush and Neale versus James Moore, a judgement was rendered.

On February 23, 1787, James Moore sells to William Hanes (both of Halifax) for 15#, 30 acres on the second fork of Birches Creek, John Poindexter line, witnesses Rice Moore, Charles Spradling and John Poindexter. James Moore makes his mark as M, Rice signs, recorded July 19, 1787.

In Brantley Henderson’s book, he mentions that winters in the “old days” were quite harsh in Halifax County. Blankets of snow would fall 6 inches deep, and the families would harvest ice 15 inches thick, storing it in the back yard in an ice pit lined with pine boards. That might well have been a later invention, but the winters probably precluded filing deeds in February.

The 1787 tax list shows James Moore with 70 acres and the 1788 tax list, with 120 acres.

In 1788, James Moore petitions the court for “reasons appearing is exempt from county levies.” It kills me that they didn’t say why. If he is age 70, then he was born in 1718.

The 1788 tax list shows him as James Moore, Sr. with 2 horses and 170 acres. It’s possible that the 7 was really a 2.

In October of 1788, Sally Moore married Martin Stubblefield. James Moore is noted as the father, with James Rice as surety and John Atkinson as the minister. James Rice may be the son of Matthew, a great-uncle to Sally Moore.

In February of 1789, Mary Moore married Richard Thompson with Edward Henderson as surety. The Reverend William Moore, her brother, performed the nuptials.

A month later, On March 10th of 1789, Manness (Mackness) Moore married Sally Thompson, with Richard Mays? as surety.

In 1790 and 1791, James Moore is shown with 120 acres and in 1791, he’s exempt.

In 1791, William Haynes sells the 30 acres of land he purchased from James Moore to Reche McGreggor bounded by Spradling’s old line, James Moore, Col. Henry.

In 1792, James Moore has 1 white poll, 1 horse and 120 acres.

In 1793, James has 120 acres and is exempt.

In 1794, Edward Henderson sold to Isaac Bare (Barr) for 30 # about 50 acres in the waters of Burches Creek and bounded by the Old Field Branch to James Henry’s line, William Moore’s line. Signed Edward Henderson. Witnesses – William Moore, Lucey Moore, James Moore. Recorded July 28, 1794

This is interesting because there is no mention of James signing with a mark, but every other signature of James is shown with a mark. This James could have been his son or William Moore’s son, James.

Lucy Moore could have been either William Moore’s wife or daughter.

In 1794 through 1797, James is shown with 50 acres and exempt.

In 1795, 1796 and 1797, there are suits against James Moore, but I can’t tell if it’s our James Moore or another.

In 1795, one James Moore signed a petition to sell the glebe land of the Anglican church. I’m not sure if this is our James Moore, or the son of William Moore, but given that this signature is on the same page as Mackness Moore, Thomas Moore and the Barr gentleman, it’s certain the same family if not our James.

In 1798, James Moore sells to William Moore 200 acres for 65# on the second fork of Birches Creek, Isac Barrs line, David Wilson, John Huddleston, Bare Branch, Little Branch, signed with the M mark, wit William Walton, Thomas Moore, Elizabeth Walton, Edward C. Henderson (also see following entry)

This Thomas Moore is either the son of James Moore or William Moore.

On the 1798 through 1805 tax list, James is still listed with the 50 acres, but the listing for personal tax is blank. If someone is exempt, they are still listed with the explanation, “exempt.”

James would have been age 80-83 by this time, and generally, the missing personal property tax would be interpreted to mean that James had died. However, given that his land remains on the list, combined with the fact that his sons left for Grainger about this same time, could cause one to wonder if James went to Grainger County in spite of his advanced age.

One final lawsuit in 1798 is James Moore versus Charles Dupreast for an attachment against defendant. William Thomas, garnishee, says he has nothing. Again, I don’t know if this is the correct James Moore.

By 1799, Mackness Moore is living in Grainger County, Tennessee. Rice Moore went with him, although it’s unknown if this was at the same time. Rice, a Methodist minister, was in East Tennessee by 1797.

In 1806 through 1811, the 50 acres remains on the Halifax County tax list when a James Moore once again emerges on the personal property tax list with 1 white poll and nothing else.

In 1812 and 1813, James Moore is shown with 50 acres, but it’s listed on Grassy Creek which would not be the correct James Moore.

Beginning in 1798, James life fades to gray, then black.

We simply don’t know what happened, or more precisely, when the inevitable happened.

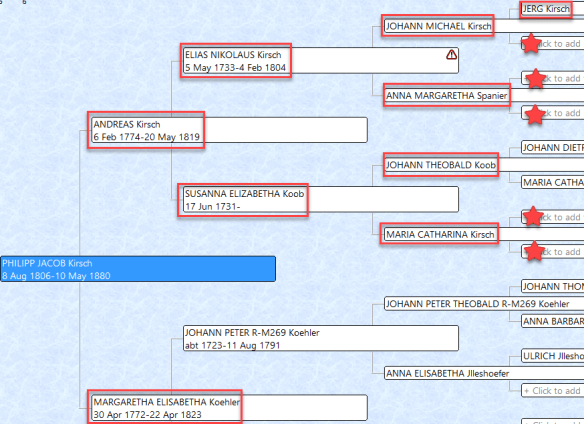

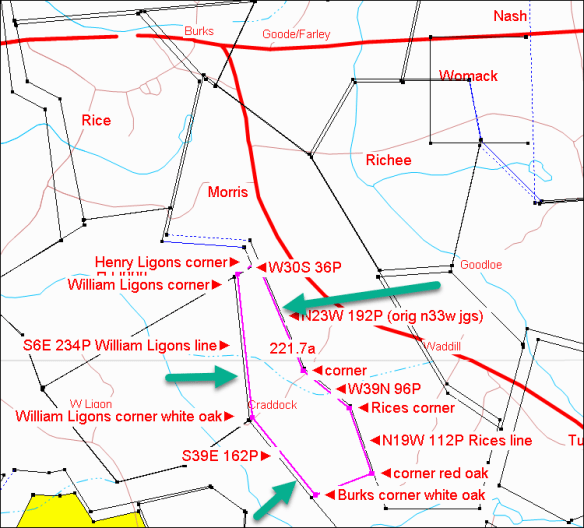

James Moore’s Land in Halifax County

James bought and sold land in Halifax County. Using DeedMapper, we have the plots of James Spradling’s two land grants, as well as that of the land James sold to William Moore.

I wrote about those in detail in the article about Lucy Moore.

In 2008, I visited Halifax County and cousin Olen was gracious enough to take me to visit the Henderson cemeteries. Yes, there are two. The original cemetery on James Moore’s land is in the woods on the land he owned, now owned by the Henderson family. The second, younger cemetery is on Henderson land that may well have been some of James’s original land as well.

While the Moore family moved on or died out in Halifax County, for the most part, the Hendersons stayed and thrived, still owning much of that land today.

Come along with cousin Olen and me as we take you with us to visit the now Henderson, then Moore, cemetery located down the 2-track known as Henderson Trail.

This is stunning, breathtaking country. That’s the Blue Ridge in the distance.

Looking around.

Drinking it in. James walked here for the last quarter century of his life.

This road still beckons to me all these year later.

Definitely on James land now.

Those branches of Birches Creek provide ponds.

Getting close to the woods where the cemetery is located.

In that clump of trees. I’m excited – we’re getting close now!

It’s early spring – the underbrush is too heavy later.

Fresh spring-green leaves just budding. Shall we find our way inside?

Periwinkle, the perennial favorite in all cemeteries in the south.

The dainty white flowers are so graceful and beautiful.

The periwinkle gives the cemetery location away with the field stones marking the final resting place of ancestors and family members, nestled in the periwinkle.

“I’m here, I’m here…,” they call.

“Did you come to find me?”

This stone looks like a stick, but it’s a stone stood sideways. Perhaps a name was originally scratched on the surface, but there is nothing now.

Trees have grown around the graves in the decades since burial, because graves could not have been dug with the roots.

This is not a small cemetery. I’m sure there are graves everyplace.

I know beyond a doubt that James Moore is here, along with wife Mary, son William and his wife, Lucy. Edward Henderson and wife Lydia Moore would be buried here too. Probably several of thier respective children too.

More fieldstones as we walk around.

I wonder if this larger stone marks James’ grave, along with the yucca plants. It looks like this grave has been better maintained than some of the others. Someone loved this person.

William Moore’s unmarried daughters are probably buried here too, as is Thomas Moore, son or grandson of James who died in 1801.

Wait, I see a stone with a name!

J. Henry Midkiff, a farm laborer, married Susanna Henderson, daughter of William Henderson and Piety Jones. I’m sure that Susanna rests here as well, beside her siblings, parents, grandparents John Edward Henderson and Sarah Clark, her great-grandparents Edward Henderson and Lydia Moore and her great-great-grandparents, James Moore and Mary Rice.

S. K. Henderson is Sarah K. Henderson whose parents were Richard Clark Henderson and Carolyn Firesheetz. Richard’s parents were John Edward Henderson and Sarah Clark. John’s parents were…you guessed it…Edward Henderson and Lydia Moore.

Sarah was five generations removed from James Moore and that was in 1845. Today Sarah’s descendants are probably 10 generations or more removed.

S. K. Henderson was married to her first cousin C. N. Henderson.

C. N. Henderson is Charles N. Henderson, the son of William Henderson and Piety Jones. William’s parents were John Edward Henderson and Sarah Clark.

Henderson Cemetery

Olen knew of a second Henderson Cemetery too, a little further down Oak Level Road, south of Henderson Trail.

This Henderson Cemetery has been indexed. The older cemetery, above, has not and is not included on Find-A-Grave either.

The oldest grave here is Richard Clark Henderson who served in the Civil War. He married Nancy Satterfield as his third wife. Richard’s father was John Edward Henderson and his mother was Sarah Clark.

This Henderson Cemetery is located across from the Oak Level Fire department, as shown on the map that Olen provided, above.

Today, using Google maps.

Approaching the cemetery.

I photographed every stone I could find.

Lots of Yucca here, although is cemetery is a field, not in the woods.

Richard Clark Henderson was the son of John Henderson and Sarah Clark. Sarah was the daughter of William Clark and Elizabeth Younger, who was the daughter of Marcus Younger and Susanna whose last name is unknown.

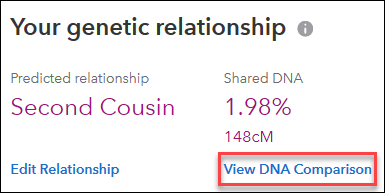

This means that my DNA matches through this branch of the Henderson family could come through the Moore line or through the Younger line. Of course, with colonial Virginia in play, they could also come via other unknown lines as well.

Olen is related to the people in this cemetery. The Younger family married into the Hendersons as well as into the Estes family. John R. Estes married Nancy Ann Moore. I’ve always wondered how these people met, because they did not live in close proximity to each other, with the Youngers on the Banister River and the Estes family in South Boston. I believe the connection was the early Methodist religion.

Nancy Henderson

This cemetery was fenced a dozen years ago, but not mowed.

I took the photos above, myself, but part of James Moore’s land is for sale today, and you can see more pictures at this link.

Tradition of Methodist Ministers

James Moore and his Rice wife, whether it was Mary or one of her sisters, had several children who migrated to Grainger County, as mentioned in the Holston Methodistism reproduced in Distant Crossroads (Hawkins County, TN) in 2003.

The County Line Meeting House was on the north side of the Holston River on the line between Hawkins and Jefferson (now Grainger) counties and was mentioned in the formation of Grainger County.

I visited and took the photo, above, where I was told that the Meeting House used to be, in front of what is now called the Coldwell Cemetery.

There are lots of Stubblefields, Dodsons and McAnally’s buried here.

Moore’s Chapel Road is very close by, but no one in the neighborhood knew where the actual Chapel used to be.

It’s a beautiful, old cemetery, and several of James Moore’s descendants are likely buried here.

Ironically, the address is Mooresburg.

However, I have since discovered that indeed, this is NOT the County Line Cemetery nor where the County Line Church was located. In fact, the County Line Cemetery is now an abandoned cemetery adjacent the Meeks Cemetery on old County Line Road.

According to locals, the old Church and homesteads are now under Cherokee Lake.

One word of caution for researchers is that several Moore lines settled in Grainger County and only Y DNA has been able to sort them out.

According to the Distant Crossroads article once again:

About the year 1792 a company of emigrants from Virginia settled here and between 1792 and 1795 organized a society. Among the original members were Martin Stubblefield and wife Sallie, Richard Thomson and wife Mary, Rice Moore and wife, John Henry Brown, Edward Rice, Amos Howell, Charles McAnally, Bsil Guess and John McAnally and wife, some of whom lived in Hawkins County. These men were all able exhorters.

Mr. Moore afterwards became an able and useful local preacher. Their wives also “(s)elect ladies” as they were labored in the cause of the gospel. Prayer and class meetings were kept up regularly from house to house. Sometimes it would happen that the men were absent holding meetings in other neighborhoods. In that event Mrs. Sallie Stubblefield would lead the meeting and would often deliver an exhortation. She was able in prayer and exhortation. These families have been represented in the ministry to the present day. Vol 1 page 136.

The Western Conference met at Chillicothe, Ohio Sept. 14, 1807. Bishop Asbury presided. A ride of 360 miles after leaving Chillicothe brought Asbury to Martin Stubblefield’s Oct 12th. There, weary as he was, he preached at night and felt powerfully disposed to sing and shout as loud as the youngest. Page 81 Volume 11

Bishop Asbury in passing through East Tennessee was accustomed to visit the Stubblefield’s at County Line. Martin Stubblefield was a favorite stopping place of his. At County Line there were 3 brothers, Thomas, Joseph and Martin Stubblefield.

Martin Stubblefield at an early day removed himself to Ohio, driving the team himself. In Cincinnati the team became frightened and ran away and killed him and he was buried there.

Not mentioned in the above article is that William Moore’s daughter, Nancy Ann who married John R. Estes had also arrived by 1820. Lemuel, probable son of James also settled here before moving on to Kentucky.

James Moore’s Children

I’ve assembled James’ proven and probable children with birthdates estimated from marriages and other legal documents where a minimum required age is known:

- James Moore, born about 1746, possibly as late as 1753, is noted as taxable with James Sr. in 1767 in Prince Edward Co. James was originally believed to have gone to East Tennessee with the other Moore men, as several James were found there, but DNA testing suggests otherwise. One James Moore whose descendant’s Y DNA matches our line is found in Stokes County, NC by 1791 and is believed to have been there earlier, having married Susanna Jones in about 1770. A James Moore Jr. witnessed a deed with a Susanna Moore in Halifax County for his father, James, in 1774. James Moore died in DeKalb County, Tennessee on March 3, 1831 and Susanna died there on July 27, 1825 according to the family Bible. They named their children Eunice, Zachariah, Thomas, Massy, Nancy and Sarah Jane.

- Lydia, wife of Edward Henderson, is almost unquestionably a Moore. Edward Henderson has a lifelong relationship with the Moore family and owns land which is sold to him by James, abutting both James and William Moore’s land. Edward and Lydia name a child Rice Henderson. Edward Henderson was born about 1746 and died in 1833 in Halifax County. It’s likely that Lydia was about the same age. James sold land to Edward in 1787 but Edward was witnessing land transactions for James as early as 1778. Their earliest known child, James Henderson was born about 1775. Other children were named Sally, Peggy, Oney, John, Rice, Edward and Mary. Edward served twice in the Revolutionary War. I have DNA matches with people who descend from this line.

- The Reverend William Moore born probably about 1750 married Lucy whose surname is unknown about 1772, likely in Halifax County, but there is no marriage record. William was a very early Methodist minister, ordained by 1775, eventually breaking with the Methodist church and was instrumental in forming the Christian Church which survives yet today in Halifax County. He died in Halifax County in 1826.

- Thomas Moore, born 1761 or before is believed to be a son of James Moore. He is found on the tax list beginning in 1783 but only sporadically. A Thomas is found in 1792, 1798, 1799 and 1800. The Thomas in the 1790s is likely the Thomas who married Polly Baker in 1798 and by 1801 had left two orphan boys, Raleigh and William. The Thomas in 1783 is too old to be the son of William Moore and may be unrelated. The Thomas Moore from the 1790s may be the son of William, not the son of James Moore. Y and autosomal DNA testing has confirmed the connection.

- The Reverend Rice Moore, born in 1762 or before, married Elizabeth Madison in 1776, moved to Greene County Tennessee by 1797, was in Hawkins the portion that became Grainger County, Tennessee before 1800 and died in 1834. Like his brother William he was a Methodist minister. He named children Elizabeth, Mary, Nancy, William and John B. Moore.

- Mackness Moore, born 1765 or earlier, married Sarah Thompson in 1789, and died after October 1844 when he wrote his will and before May 19, 1849 in Grainger Co., TN. Rice and Mackness both left Halifax County before 1800. Mackness named children Mastin, John, Elizabeth, James, Samuel, Sarah, Sally and Richard.

- Sally (Sarah) Moore was born about 1767 and married Martin Stubblefield in October 1788 with James Rice as surety. This family also migrated to Grainger Co., TN, naming their children Nancy, Rebecca, James, Mary, Elizabeth Ann and Robert Wesley.

- Mary Moore, probably born before 1769 was married to Richard Thompson in February 1789 by the Rev. William Moore with Edward Henderson as surety. The Richard Thompson family is in Grainger Co. with the other Moore siblings. Their children were named Mary, William, James, John and Frances.

- Lemuel Moore, born before 1777 is thought to be the son of James Moore. Lemuel Moore is found in 1797 in Greene County, TN beside Rice Moore. One Lemuel Moore is found on the tax list in Halifax County in 1801, but not in the following years. Lemuel Moore married Anna Stubblefield in 1804 in Grainger County and died in 1859 in Laurel County, Kentucky. I have several DNA matches with descendants of this couple.

Another Lemuel Moore is found in Halifax County in 1812 on the tax list, still there when an 1825 debt suit is filed against him, but is found in 1830 in Grainger County. I believe the elder Lemuel is the son of James Moore and the one found in Halifax County between 1812-1825 is probably the son of William Moore. Lemuel is sometimes spelled Samuel.

I found a document in the chancery files where on November 2, 1812 where George Estes, his son John R. Estes (who married Nancy Ann Moore, daughter of William Moore) and Lemuel Moore (proposed brother of Nancy Ann) all 3 signed a deposition in a lawsuit pertaining to Phoebe Combs, related to John R. Estes. This is highly suggestive that the Lemuel in 1812 is the son of William Moore, and the Lemuel who left Halifax County before 1800 is the son of James Moore.

Y DNA

Based on the associations of James Moore with his neighbors, and his marriage into the Joseph Rice family, I was pretty well convinced that our Moore line was English. I might have been wrong.

Now, there’s the matter of a pesky Y DNA match to a man who claims his paternal line is from Scotland. He hasn’t answered e-mails yet, but I’m still hoping.

There were Moore families involved with the Cub Creek settlement which was Scotch-Irish, but James, to the best of my knowledge, doesn’t seem to be associated with that group. However, the dissenting meeting house built in 1759 by his father-in-law clearly wasn’t Anglican. Baptists have no concentrated history in the county that early and neither do Methodists. That leaves Presbyterians.

- Is the new Y DNA match wrong about his ancestral line?

- Was James Moore actually Scotch-Irish?

- Did James meet and marry Joseph Rice’s daughter in Amelia County, or, did he marry her in Hanover County, joining with his father-in-law in the “Hanover migration” to Prince Edward County sometime after Joseph Rice is last found in the merchant accounts in 1743 in Hanover County?

- In 1741, Joseph’s brother Matthew acquired land in Amelia County and in 1746, so did Joseph Rice, both on the Sandy River.

- Matthew Rice married Ann McGeehee, a Scotch-Irish woman.

So, there is indeed at least a tenuous Scotch-Irish family connection.

A Late-Breaking Clue – Betsy McGinnis

According to her Revolutionary War pension application, Betsy McGinnis was married in the spring of 1785 to William Morris in Halifax County by her cousin, Rev. William Moore who was a minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church.

This may be a HUGE hint, because if Betsy and William Moore were first cousins, that means they shared grandparents. Of course, cousin could have been used more liberally, but clearly Betsey and William knew they were related.

William Moore’s parents of course were James Moore and the daughter of Joseph Rice.

We don’t know who James’s parents were, and Joseph Rice’s wife was named Rachel at his death.

Therefore, if we can figure out the genealogy of Betsy McGinnis, specifically who her grandparents were, the James Moore brick wall may fall. Either that or the wife of Joseph Rice might be identified.

If you descend from James Moore or Joseph Rice, will you please check to see if you have any matches to people who descend from William Morris born in 1758 in Halifax County, VA and died in 1824 in DeKalb County, GA and his wife Betsy McGinnis who was born about 1761 and probably died in 1841 in Dekalb County? If you match, please let me know.

It seems we are often left with more questions than answers, but I just feel this answer is so, so close.

Doggone it, James Moore, WHO ARE YOU AND WHERE DID YOU COME FROM?

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

Like this:

Like Loading...