There’s more that we don’t know about Françoise than we do.

We can infer some information from the facts we have.

Françoise Mius was born between 1684 and 1687, probably closer to 1684, in a Native village. Probably in or near Pobomcoup, Acadia, now Pubnico, Nova Scotia where her (presumed) father, Philippe Mius II, was raised. Philippe was the son of the most prominent Frenchman in Acadia by the same name, and her mother was a Native woman reported to have been from a Mi’kmaq village, Ministiguesche, near present-day Barrington.

By the way, according to the Nova Scotia Archives, the correct pronunciation of Mi’kmaq is ‘Meeg-em-ach.’

Did you notice all those words of uncertainly describing Françoise Mius, like multiple instances of probably and presumed? We’ll work through each one.

The first record of Françoise is the 1703 census at Port Royal, where she is listed with her husband, Jacques Bonnevie, and their two eldest children, both girls.

A total of about 85 families are living near Port Royal.

This family is NOT shown in the 1700 or 1701 census anywhere. Given that they had two children in 1703, they would have been married about 1700. The remaining parish records in Port Royal begin in 1702, and their children are not shown as baptized there.

However, the Port Royal parish registers, on October 22 and 23, 1705, show that several mixed Native/Acadian children were baptized who were previously baptized at Cape Sable, or nearby. Residences of their parents include Outkrukagan, Pombomkou, Puikmakagan, OneKmakagan, Mirliguish, Petite Riviere, Merligueshe, Port Multois, and Kayigomias.

Along the Eastern Coast, Mi’kmaq were seasonally migratory and also located near Canso, River Sainte Marie, Chebucto, La Heve, Port Medway, Port Rossignol (Shelburne), Ministiguesch (Port La Tour) and Ouimakagan (near Pubnico). For a more detailed discussion of these village sites, see Bill Wicken, “Encounters with Tall Sails and Tall Tales: Mi’kmaq Society, 1600-1760”.

Merligueche is noted in this list of villages, and it turns out to be an especially important place for the Mius family.

Photo courtesy of the Nova Scotia Archives.

Merligueche was also the location of a large Mi’kmaq summer village and trading port.

This cluster of 1705 baptisms within a day or so of each other makes me wonder if there was some kind of community baptismal event where everyone who wanted their child officially baptized climbed into a canoe or fishing boat and set out for Port Royal, where they had access to a priest. Conversely, the gathering could have been a harvest festival, Mawio’mi (powwow), or celebration of some type. One thing is clear, lots of non-resident people were visiting Port Royal that weekend and they probably didn’t visit regularly since the children being baptized were born across several years.

Many people were recorded with place names for surnames like Anne de Pobomkou.

There was only one Catholic church on the western shores of Acadia – at Port Royal. We know that children were born elsewhere and baptized at birth as they could be, even without a priest, which may have been the case for Françoise Mius’s two eldest daughters. Unlike others, they were never rebaptized at Port Royal, or, those records no longer exist.

It’s interesting that “Philippe de Pobomkou,” who signed as Philippe Muis, baptized children in 1702.

“Sieur de Pobomkou” baptized a child in 1704, which would have been the elder Philippe Mius. “de Pobomkou” was used synonymously with Mius. Philippe Mius and his son were the highest-ranking Frenchmen in Acadia during their lifetimes and were quite well respected. Philippe Sr. had arrived in 1651 as a Lt-Major to his friend, Charles La Tour.

Philippe Mius Jr. lived among and married into the Mi’kmaq tribe, although he clearly kept many of his French ways, including the Catholic faith.

Both the Mius and LaTour families married into the Native families. This was not frowned upon or discouraged. An attitude shift developed sometime later.

We don’t know why, but something was motivating some of the mixed Acadian/Mi’qmak people to move to Port Royal. Jean Roy dit Laliberte, who was the shoremaster for Charles St-Etienne de La Tour and Jacques Mius, and his Native wife moved to Port Royal by 1698, and we know that Françoise Mius and Jacques Bonnevie were there by 1704. Of course, their motivation could have been because Jacques was a soldier. I noticed that some of the same military men were witnesses for other rehabilitation baptisms of the children of mixed couples that moved up from the Pobomcoup area.

On May 31, 1704, son Jacques Bonnevie was born and baptized the next day, listing “Françoise Muis dit Beaumon” as the wife of Jacques Bonnevie

- Register RG 1 volume 26 page 20

- Priest Felix Pain

- Registration Date 1 June 1704

- Event Baptism

- Name Jacques Bonnevie

- Born 31 May 1704

- Father Jacques Bonnevie

- Mother Françoise Muis dit Beaumon

- Godparents Jacques de Teinville

- lieutenant of a company

- Magdelaine Mellansson ditte de la Boulardrie

It’s worth noting here that the Godfather is indeed the lieutenant of a company.

Françoise’s husband, Jacques Bonnevie, was reported in 1732 to be a retired, disabled soldier.

Seige!

One month and one day after that baby was baptized, two English warships and seven smaller vessels entered the Port Royal basin, capturing the guard station opposite Goat Island, along with four Acadians.

A woman from a family who had been captured was sent to the fort to demand surrender. It’s unclear if this was a separate family or the four that we know were captured.

For 17 long days, the men in the fort awaited an attack. However, the fleet commander had moved on to Grand Pre where the English laid waste to the town before returning to exchange perfunctory gunfire with the fort at Port Royal before returning to Boston.

Much of the English harassment and attacks upon Acadia were coordinated out of Boston.

The siege of Port Royal lasted only 17 days. This time. With a newborn infant plus two young children, and her husband stationed inside the fort, anticipating an attack at any minute, Françoise must have been terrified. She was also alone because, as a soldier, Jacques had no family there, and as a half-Native woman from far-away Pobomcoup, neither did she.

Perhaps families sheltered inside the habitation. Perhaps Françoise took her children and retreated into the safety of the woods, relying upon the skills she learned among her family.

Life in Port Royal

Their next child, Marie Bonnevie, was born and baptized on May 12, 1706 in the Catholic Church near Port Royal.

- Bonnevie Marie 1706

- Register RG 1 volume 26 page 47

- Priest Justinien Durand

- Registration Date 12 May 1706

- Event Baptism

- Name Marie Bonnevie

- Born 12 May 1706

- Father Jacques Bonnevie

- Mother Françoise Mius

- Godparents Louis de Clauneuf [Closneuf]

- lieutenant of a company

- Françoise de Belle Isle

Again, the Godfather was the lieutenant of a company.

In 1707, the family was listed in Port Royal under the name of Jacques Bonneur, his wife, 1 boy less than 14, and three girls less than 12. The family is living on 1 arpent of land, with 2 cattle and 6 hogs. One arpent of land is clearly not enough for farming, but given that Jacques is a professional soldier, he is probably stationed at the fort and is paid for his service. Their land would be used for a garden plot and raising their livestock.

They live two houses away from Madame de Belle Isle, a widow who may well be related to the Françoise de Belle Isle, who stood as Godmother the year before. Madame de Belle Isle is Marie Saint-Etienne de LaTour who was the widow of Alexandre Le Borgne de Belle-Isle. They lived in Port Royal, and she was widowed by 1693, becoming important in her own right as a seigneuresse, managing the finances of her former husband, a seigneur, allotting and selling land among other responsibilities.

Soldiers do not appear on the census. Most returned to France at the end of their service, but some stayed, married, and settled into Acadian life.

A total of 106 families are enumerated.

On February 21, 1708, Françoise Mius, wife of Beaumont, stood as the Godmother of Anne Clemenceau, daughter of Jean Clemenceau and Anne Roye. Anne Roy was also from Cape Sable and half-Native. Her father worked for the LaTour and Mius men.

Françoise would have known Anne before they both moved to Port Royal. They spoke the same language, shared cultures, and may even have been related.

Between 1708 and 1715, Françoise would have had at least four additional children, but we have no record of their births or deaths.

The Conquest of Acadia

In 1710, the English attacked Port Royal once again, but this time armed with warships and 3400 troops.

Again, a siege ensued.

Those brave men managed to hold the fort for 11 days, but in the end, had to relinquish control. 300 men, some of whom were poorly trained new recruits, stood no chance against the mighty English warships. Plus, they were outnumbered by more than 11 to 1.

The English warships fired upon the fort all night, and their cannon had advanced to within 300 feet of the fort. It became evident that either they negotiated the best possible surrender conditions, or die. Either way, the English were going to take control of the fort, and with it, Acadia.

The English allowed the Acadian and French men to exit with at least their lives and what was left of their dignity, flags flying and drummers drumming.

This event became known as The Conquest of Acadia and ended French rule.

Françoise must have been incredibly relieved – not that the Acadians lost their homeland, but that Jacques wasn’t killed and the French soldiers were released. I do have to wonder how and when he became disabled, and if it was related to this event.

A year later, the Acadian men and the Mi’kmaq warriors attempted a siege of the now-English fort, which failed.

Living Under English Rule

Day-to-day life didn’t change much under English rule, at least not initially. The Acadians were permitted to continue Catholic worship, and the routines of the seasons dictated daily activities.

The English only took one census.

In the 1714 census, “Beaumont” was listed with his wife, one son, and three daughters at Port Royal. His career as a French soldier at the fort had clearly ended, although life must have been extremely uneasy for those previous soldiers.

How would they have earned a living? The English certainly weren’t going to give them land.

On October 13, 1715, their son, Charles Bonnevie, was born and baptized.

- Register RG 1 volume 26 page 137

- Priest Justinien Durand

- Registration Date 13 October 1715

- Event Baptism

- Name Charles Bonnevie

- Born 13 October 1715

- Father Jacques Bonnevie

- Mother Françoise Mius

- Godparents Charles Landry

- Marguerite Pitre

- wife of Abraham Comeau

When Was Françoise Born?

Unfortunately, not one single record gives Françoise’s age. Not one.

If Françoise had two daughters by 1703, with the next child, Jacques, born in May of 1704, we can surmise that the youngest daughter was born in 1702 or maybe early 1703, 18-24 months before Jacques. Françoise’s oldest daughter would have been born about 2 years before that, so about mid-1700 or perhaps in 1701.

This suggests that Françoise Mius was married in either 1699 or 1700, which puts her birth at about 1680-ish. Some researchers show her birth between 1684 and 1687. 1684 is after the birth of known children of Philippe Mius with his first wife, and 1687 is the approximate birth of the first of the next group of Philippe Mius’s children with a Native woman named Marie.

All things considered, I’m using 1684 as her birth year.

If you’re thinking, “This sure is complicated,” you’d be exactly right.

Who Are the Parents of Françoise Mius?

This is where it gets a little dicey.

There are only four known Mius men in Acadia at this time, all of whom are well-known and documented. Some can be reasonably eliminated from consideration.

Philippe Mius, the elder, and father of the other three, was born in France around 1609, married Madeleine Helie around 1649, presumably in France, and had five known children between 1650 and 1669. Sometime around 1651, Philippe came to Acadia with his young family as Lieutenant to Charles de Saint-Etienne de La Tour and served as commander of the colony in La Tour’s absence. We will hear his story later.

- Philippe Sr.’s eldest son, Jacques Mius d’Entremont, was born about 1654, married Anne Saint-Etienne de La Tour (1661-1741) about 1678, and died about 1735.

- Philippe Sr.’s second son, Abraham Mius de Pleinmarais, was born about 1658 and married Marguerite Saint-Etienne de La Tour (1658-1748) about 1676 and died about 1700.

Both of these sons had married European women long before the 1680s when Françoise was born.

- Philippe Sr.’s third son, Philippe dit d’Azy Mius II, was born about 1660, lived among the Native people, and was married to two Mi’kmaq women.

We know, based on the mitochondrial DNA haplogroup of our Françoise Mius, X2a2, that her mother was indeed Native, which limits the choice of father for Françoise, barring an unusual circumstance, to son Philippe Mius.

This early photo of a Mi’kmaw woman, Mary Christianne Paul Morris, was taken in 1864. She is holding a quillwork model canoe, and a quillwork box rests on the floor by her leg. She is dressed in traditional attire. Photo courtesy of the Nova Scotia Archives.

Early Census Records

Philippe Mius Sr. is shown on the 1671 census of Acadia at the Habitation of Poboncom near the Island of Touquet as follows:

Phillippe Mius, squire, Sieur de Landremont, 62, wife Madeleine Elie 45; Children: Marguerite Marie An, Pierre 17, Abraham 13, Phillippe 11, daughter “la cadette” Madeleine 2; cattle 26; sheep 25.

In the 1686 census, we find:

Philippe Mius, royal prosecutor, age 77, is shown in Port Royal with son, Philippe, 24, daughter Magdelaine 16, and 40 arpents of land. It’s worth noting that both of his sons Jacques and Abraham are married with children and living in Cap Sable beside or near the LaTour family whose surname is sometimes written Saint-Etienne de La Tour.

These two censuses show his birth year as 1660 and 1662.

The 1708 Census

In the 1708 census, which includes both French and Native families, in the section titled “Indians from La Heve and surrounding area,” we find:

- Philippe Mieusse age 48 (birth year 1660)

- Marie his wife 38 (so born about 1670)

- Jacques his son 20

- Pierre his son 17

- Françoise his daughter 11

- François his son 8

- Philipe his son 5

- Anne his daughter 3

This daughter, named Françoise, is only 11 and, therefore, cannot be our Françoise, who was married by about 1700 and had children shortly thereafter.

We do find a few more people with the surname Mieusse:

- Cape Sable under enumeration of the French: François Vige, age 46, his wife Marie Mieusse 28, with 5 children. Marie’s age of 28 puts her birth in about 1680.

- Indians from Mouscoudabouet (Now Musquodoit Harbour): Maurice Mieusse 26 with wife Marguerite 27 and two children. Age 26 puts his birth at about 1682.

- Cape Sable Indians: Mathieu Emieusse 26, Madelaine 20 and one child. This puts his birth at about 1682.

- De La Heve under “enumeration of the French”: Jean Baptiste Guedry 24 and Madelaine Mieusse 14. Age 14 puts her birth at age 1694.

Another child of Philippe Mius Sr. is found three houses away from François Vige and Marie Mieusse:

- Joseph dazy 35, Marie tourangeau 24, with 5 children. His age places his birth about 1673. His death record on December 13, 1729, at about 55 years of age, by the name Joseph Mieux dit D’Azy, confirms his identity. His surname line among descendants was known as D’Azy.

Neither Françoise Muis nor Jacques Bonnevie is shown in 1708 under the only Port Royal category of “Indians of Port Royal.” They are considered French and live among the French families.

Philippe Mius’s Older Children

Given the age of Philippe’s wife, Marie, in 1708, she was born about 1670.

This means that it was impossible for Marie to be the mother of Philippe Mius’s oldest children, including Françoise. His older children were:

- Joseph d’Azy Mius, born about 1673/1679, received land in 1715 and is described as “part Indian who dwelt at Port Le Tore,” and is the son-in-law of “Tourangeaut”.

We know that Philippe Mius Jr. was born around 1660, which is probably why researchers have shifted his son Joseph d’Azy’s birth closer to 1679. Various records across the years clearly show Joseph as being half-Native.

He is later noted as the “part Indian who dwelt at Port Le Tore,” which was originally known as Port Lomeron and was where Charles La Tour lived.

This map shows Port LaTare, aka LaTour, along with the other capes and early forts.

La Tour traded here between 1624 and 1635 when he established another fort at the mouth of the River Saint John.

Author Father Joseph Clarence d’Entremont states that Philippe Mius’s first unknown Mi’kmaq wife who was the mother of Françoise Mius was from what is today Barrington, Nova Scotia. Based on the 1708 census, Philippe Mius’s second Native wife, Marie was probably a member of the Le Heve tribe. Barrington may have been the village of Ministiguesche according to the authors of the Ethnographic Report.

Several of Joseph Mius’s children intermarried with the Mi’kmaq people, as did two of his full siblings, shown below:

- Marie Mius, born about 1680, married Francois Viger. They lived at Ouimakagan, present-day Robert’s Island, near Pobomcoup in 1705.

- Maurice Mius, born about 1682, married Marguerite, a Mi’kmaq.

- Mathieu Mius, born about 1682, married Madeleine, a Mi’kmaq

- Françoise Muis, born about 1684, married Jacques Bonnevie, a French soldier.

Maurice and Mathieu are shown as twins, born in 1682, and Françoise is slotted as the next child, born in 1684.

That’s certainly possible, as she would have been 16 in 1700, and young women were clearly marrying at that age in that time and place.

There is no evidence or suggestion that the other Mius men, meaning Philippe Sr. or his sons Jacques Mius d’Entremont or Abraham Mius de Pleinmarais, had children with a Native woman in the 1680s.

Of course, that also doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.

Given the age of Philippe Mius’s Native wife, Marie, born about 1670, she cannot have been the mother of those older Mius children.

Adding to the confusion, Philippe had daughters named both Françoise and Marie with both Native wives, although the children may well have been called by their Native names, not their French baptismal names.

Facts About Françoise

So, we know a few things, for sure:

- Françoise was shown in the parish records as Mius and Mius de Beaumon(t)

- Françoise’s mother was unquestionably Mi’kmaq, confirmed by mitochondrial DNA

- Françoise was having children by 1700/1701, so probably born no later than 1685

- Assuming that her father was a Mius male, the only candidates were Philippe Sr., Philippe Jr, Abraham, or Jacques

- Philippe Sr., Abraham, and Jacques were married to European wives at that time.

- Philippe Jr. is documented to have been living with the Native people and, according to various records, had two Native wives

- Françoise’s mother was very unlikely Philippe Jr.’s second Native wife, Marie, as she was born about 1670, so would have been a prepubescent child when Philippe’s oldest children were born, and about 14 when Françoise was born

- Françoise’s mother was very unlikely Philippe Jr.’s second Native wife, as she named another daughter Françoise who was born in 1697.

Constant Conflict

Acadia was in a state of constant conflict, with the English either attacking or threatening to attack at all times.

These conflicts began before Françoise was born, but one of the more memorable took place in 1690, when Françoise was a mere child. The Battle of Port Royal was fought, resulting in the fort’s surrender. That should have been the end of it, but it wasn’t, as the English burned the town and many farms before forcing the residents to sign a loyalty oath, taking a few hostages, and sailing back to Boston. A few weeks later, more English arrived to pillage anything that was left.

While Françoise would have been tucked safely in a Mi’kmaq village someplace in Southwest Acadia, this back-and-forth scenario and broken trust played out over and over again.

Beginning in 1713, the English, who had been in control of the Acadian homeland since 1710, tried to force the Acadians to sign “better” loyalty oaths to the crown. When they refused, the English tried to evict the Acadians, only to change their minds because they needed their labor to feed the English soldiers.

The unrelenting conflict with the English was ramping up again.

The Acadians wanted to and tried to depart for Ile Royal, but were stopped by the English Governor.

In 1715, the Fort’s gates were shut and locked, preventing trade with anyone, including Native people.

In 1717, Captain Doucette became the Lieutenant Governor of Acadia. By this time some Acadians had decided to stay put on peaceful terms. When the Indians learned about this, they threatened the Acadians. Though they had always been friends, and in Françoise’s case, relatives, the Indians didn’t want the Acadians defecting to the English side.

By now, everyone was upset and everyone was mad at everyone else.

Doucette demanded that the Acadians take the oath, but they thought doing so would tie them down … and they still wanted to move. The Acadians said that if they were to stay, they wanted protection from the Indians, and the oath would need to be stated so that they would not have to fight their own countrymen. But that negotiation tactic wasn’t working, because Doucette wanted an unconditional oath.

The only constant in Acadia other than Catholicism was warfare.

Given that Françoise was half-Native and given the nature of the conflict between 1710 and 1720, I wondered if perhaps Françoise and her husband, Jacques Bonnevie, struck out for parts unknown, or at least undocumented.

I quickly discounted that possibility, because their children are found in Port Royal. They wouldn’t have left them behind with no means of supporting themselves.

By 1718, Françoise’s children began to marry, and in 1719 her first grandchild arrived. Her husband, Jacques Bonnevie, stood as Godfather at the baptism, but Françoise did not stand with him. She is not found in any record again.

Clash of Cultures

Constant warfare isn’t the only undercurrent running through Acadian lives – or, more accurately, through Acadian/Mi’kmaq mixed lives.

This painting, “Homme Acadien,” Acadian Man by André Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, is reported to represent a Mi’kmaq man somewhere in the Acadian region. Looking at this man, I’m not at all sure he’s native, or at least not fully Native.

Every genealogist knows about assumptions, and we all try to avoid them. Sometimes we don’t even realize we’re assuming. Once in a while, assume gets us.

I’ve been researching Acadians and Native peoples for decades now, and I know that the Acadians were closely allied with the Mi’kmaq and probably other Native peoples too. The Maliseet lived in the Saint John River drainage, and both the Penobscot and Abenaki are found in and near the early Acadian settlements, particularly those on the mainland in New Brunswick and present-day Maine. The Acadians and Native people intermarried. The Native people helped the Acadians and lived near and sometimes integrated with their villages. They were hunting and trading partners.

Everything seemed hunky dory.

Like every place Europeans colonized, they attempted to convert the aboriginal people to their religion. We know from parish records in Acadia and elsewhere that many Native people were baptized and given European religious names.

And yes, we know that Native people and Acadians intermarried. The Catholic Church would not sanction a marriage unless both parties were Catholic, so the Mi’kmaq converted. Although it’s very doubtful that the Native people understood conversion to be what the French assumed. Still, the marriage happened, which was the point.

A list of Mi’kmaq marriages extracted were by Fran Wilcox from the Port Royal parish registers beginning in 1702 and published by Lucie LeBlanc Consentino. Another list with genealogical information can be found at WikiTree here. Stephen White’s list is available here. Some “marriages,” meaning in the legal or religious sense, are inferred.

There were rumblings of unrest between the two groups of people from time to time, especially when the Native people became concerned that the Acadians might be planning to side with the English, and against them, but nothing at all that seemed serious. Nothing suggested or even hinted that ethnic discrimination played into the equation. In fact, I thought just the opposite. People intermarried, and the blending seemed smooth. No boats seemed to be rocking.

I was wrong.

In the document, “An Ethnographic Report on the Acadian-Metis (Sang-Meles) People of the Southwest Nova Scotia,” I learned a lot – a whole lot. The authors provide a download copy, here, for noncommercial use, and I encourage Acadian researchers to download and read the document in its entirety.

This treatise was written by academics who are also Acadian descendants, specifically Acadians who carry both French and Native heritage. Little that I learned was pleasant.

To begin, let’s define a few terms.

- French people – people from France and not yet Acadians

- Acadian people – people who came from France and settled in Acadian, now Nova Scotia, and established a separate, unique culture over time

- Mi’kmaq First Nations people – Aboriginal inhabitants of Nova Scotia, Atlantic Maritime Canada, and the northeast US

- Metis – In Canada, mixed race between French/Canadian and First Nations. Initially, metis simply meant a person of mixed parentage, but today, there is an official “Metis” tribe, and the identity and definition have become complex.

- Sang-Mêlés – defined in the Ethnographic document as people who were mixed Acadian/First Nations, perceived as an “inferior caste of people” both before and after the Deportation in 1755

- Bois-Brûlé – this term is applied to the descendants of Joseph Mius d’Azy whose father was Philippe Mius Jr. and mother was Mi’kmaq, and the descendants of Germain Doucet, born in 1641, whose father was Native. People referenced by this term live in Tuskey Forks/Quinan, Nova Scotia.

The authors found distinct, documented marriage patterns where parents who were members of the “Pur” caste, meaning those who were not admixed with Native people, would go to extreme lengths to ensure that their children did not intermarry with those who were mixed, specifically the “caste dêtestée des gens mêlés,” which translates to “detested caste of mixed people.” This was particularly pronounced in the Cape Sable region where the Mius descendants are prevalent, both pre-deportation and after members of the Mius and Doucet families returned after the Exile.

It hurts my heart to even type these words. I was truly shocked. This was not at all what I expected.

But it also explains A LOT in my own family. I had a HUGE AHA moment.

The authors point out that the degree of blood quantum, or the generational distance between the individual being discussed and their original Native ancestor makes no difference at all.

This reminds me of the dreaded “one drop rule” in portions of the US, specifically stating that anyone with even “one drop” of nonwhite blood was considered to be non-white or “colored.” Of course, discriminatory practices were visited upon anyone non-white in the 20th century and earlier.

The authors stated that even recently, one of the greatest insults to an Acadian would be to tell them that they had Native blood.

These families often intermarried within their community or with newcomers and established a distinct culture separate from the Acadians, Mi’kmaq, or, more broadly, the French/Canadian Metis.

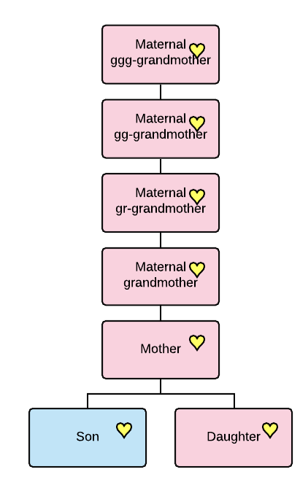

My ancestry reaches from my mother to Françoise Mius as follows:

- My mother

- Edith Barbara Lore 1888-1960, who knew absolutely nothing about Acadian heritage and nothing about her father’s past before meeting her mother

- Curtis Benjamin Lore 1856-1909 – A man with a mysterious past that he attempted to escape.

- Antoine “Anthony” Lore 1805-1862/1868 – His family never knew he was Acadian As a young man, he left a high-drama family situation in L’Acadie, Quebec, and died, perhaps as a river-pirate in Pennsylvania. Another mysterious man.

- Honoré Lore 1768-1834 – Born in New York during the Acadian exile.

- Honoré Lore/Lord 1742-1818 – Born in Acadia, exiled in New York, settled in Quebec.

- Jacques “dit LaMontagne” Lore/Lord, probably the son of a soldier, was born about 1679 in Port Royal. He married Marie Charlotte Bonnevie who was born about 1703 to Françoise Mius and Jacques Bonnevie, probably in Pobomcoup, and was one-fourth Native.

- Françoise Mius born about 1684 – Half Native through her unknown mother, who was married to Philippe Mius II sometime around 1679

Even 4 or 5 generations later, my mother’s grandfather and great-grandfather were very evasive and behaved in a manner that suggested they were trying to escape or avoid something. That fear and perhaps cultural avoidance had been passed from generation to generation.

Mother didn’t know they were Acadian, didn’t know she had Native blood, and didn’t know about her grandfather’s past. Neither did her mother and I doubt his wife, mother’s grandmother, did either.

Of course, that’s my perspective – it’s not from the perspective of the Acadian people, not from the perspective of the Sang-Mêlés, and not from the perspective of any of those people mentioned. I wonder about the adage, “Once burned, twice shy.” Once something is revealed, it can’t be “unseen.”

Betrayal was a constant concern.

So, my Acadian ancestors moved away and chose not to reveal a past that had burned them previously. Catholic, Native, poor, and Acadian were all things that could burn you again. Anything that wasn’t part of the mainstream, in line with the people in power, put you at risk.

Prior to the arrival of the French, before the arrival of the priests, the Native people enjoyed and functioned perfectly well within their own culture. They had their own standards, rituals, and customs about marriage and morality, how it worked, what was acceptable and what wasn’t – in their community and environment. The colonizers had other ideas and judged the Native people, their culture, and their descendants, who still bore at least traces of both Mi’kmaq culture and blood, from their pulpits and their seats of government.

A priest, Father Jean-Mande Sigogne, who served in the Cape Sable area for more than a quarter century, beginning in 1800 when he arrived in a fishing boat, was incredibly frustrated for more than a quarter century by both the behavior of the Sang-Mêlés families AND by the blatant discrimination exhibited by members of his parish who weren’t related to those families – and certainly didn’t want to be. In 1802, he wrote the following letter to church elders and mentioned that the denigration of the Sang-Mêlés was a widely accepted practice.

There reigns here a prejudice that seems to be contradictory to the charity and the spirit of the religion and also of the church because it has been carried too far, and it is supported by authority and the custom of the area, and even by the clergy. It is the marriage that is contracted or to be contracted between those who are called Whites and others who they call sang mêlé, which is not accepted by people here, despite the equality of conditions to others, superiority in wealth, and of virtue and talent. Some people prefer to see their children unmarried than to see them married into the families that are even slightly tainted, and most prefer that they marry to the degrees that are prohibited by the church: so that they have more respect for their vain prejudice than for order and rule in the church. We can see here that there is a refusal to marry any young man with any drop of Savage blood. This is new and ridiculous to me, I have never heard of such irregularities. I have found no canon from the ancient church of Africa that mentions similar; there seems to have been Roman families that were allied with the African families. This prejudice seems difficult to destroy; I said something in public, but with precaution so I would not offend the spirits; but I have been ridiculed for this on occasion; It makes me angry that to Marry couples is in violation of the laws of the church because one of the ancestors of their great-grandfathers married a Savage, perhaps more Christian than them. I wait with submission and respect for your opinion on this prejudice, your Greatness.

Father Sigogne railed against the inherent racism and denigration of the mixed Native/Acadian people in the same treatise where he called their blood “tainted.” He said in one case that the “Sauvage” might have been more Christian than a member of his own parish, yet their cultural norms frustrated him to tears.

In 1809 he wrote:

There exists here a prejudice that I believe to be unchristian, not very charitable and little just in itself. [Those in] my world have a horrible repugnance to unite with those who have what they call mixed-blood. I mean with those whose families come originally from the marriage of a Frenchman with a savage woman and vice versa; they even have a sovereign contempt for those with merit and even superior. I openly attacked this foolish prejudice to the exemptions and I have much displeased the people who have, they say, pure blood. I still fight it, though with more reserve. But people with mixed-blood, for the most part, behave so badly that they cover me with confusion for having defended them, and are truly worthy of the contempt of them. They indulge without discretion all sorts of vices. Disorders of every kind reign among them in an eminent degree. They have, it seems, passions stronger than the others, or the contempt of them reduces them to the point of having no sense of virtue or honor.

He goes on to ask for marriage exemptions for four couples who are mixed and are related to either the second, third, or fourth degree of sanguinity. In one case, the couple was related twice, through both the second and third degree. These marriages are all between the descendants of the mixed Mius and Doucet families.

The Mius family, Doucet family, and the Native people were very closely allied and, by this time, had been interrelated for generations.

If you cannot marry into the “general population,” there is no one left to marry other than people within your “caste.” The priest at one time said he had hoped that the English men would convert to Catholicism and marry within this group, but that didn’t happen.

In 1813, while attempting to assist the Mi’kmaq acquire land, which is incredibly ironic since they were the aboriginal population, he noted that Andrew James Meuse was the chief of the local tribe. He went on to describe the desperate state of the Mi’kmaq people and that people often took advantage of them. He tells of Mi’kmaw walking from as far as 300 miles carrying packs and children. You can read more here.

By 1826, the priest had not given up and clearly remained extremely frustrated after more than a quarter century of living among and working with these families. He wrote the following in a sermon:

I am forced to tell you here, O people whose blood is mixed, if you are fleeing, if you disdain, if we refuse to ally with you, is it not because of your bad conduct, scandals & disorders that reign openly among those of this caste, more than among the others? Indeed, have we not seen & not seen yet from time to time actions that make us blush & move our neighbors away from our church, seeing in it the reign of adulterers and public concubinages? & that among you, degenerate race, corrupt and incestuous race. It is necessary to tell you the truth; upon my arrival, sincerely believing before God that the contempt which I perceived they were making of you was not very charitable, I took your side because charity covered in my eyes the multitude of your sins & that I wished that the past be forgotten, and that by forming new establishments for the civil and the religion, I did not expect my care and my ministry to see reign among your union, faith, marital harmony, purity of morals, probity, temperance, and sobriety; this is the fruit that I expected from my labours by doing catechisms carefully & the first communions with solemnity. I was waiting, yes, I was waiting for all this, and not less than that of you; and that is the principle of indulgence and favour that I showed you to the scandal and reproaches of others who have given me enough testimony [sic] of their dissatisfaction. But alas, to my great sorrow, I soon saw by the wrinkle of the promises made, by the terrible scandals which have appeared, that it is necessary, by blushing at your conduct, that I change my manner of thinking about you. So I promised myself that I would no longer encourage or support disputed unions because of the stain of mixed blood, leaving the rest to God. This is before God, oh Christians, the simple exposition of my heart. You can now see who you are going to; it is my misfortune but it is not my fault. It is true, however, that there are families in the mixed caste whom I cannot reproach; so I make it a point to do them justice and to respect them, but the justice and respect which I owe them, and which I am, disposes of their render must not go to the point of leaving vice unpunished; it is an accident for them to be among those families, but I cannot help it; so I pray those to take in good part what I did & what I say. I measured and weighed my words before God. It is with vices, it is with the disorders, it is with scandals that I make war, it is to drunkards, rebels, old [sic], adulterers, public concubinaries and none who approve and support them, whether they are white or tainted families, pure or mixed, that my reproaches are directed & not to those who live as Christians, whatever they are. May the misguided and the vicious, the incestuous, and the adulterers return to the true path, to virtue and good order, in a word to penance, my reproaches will no longer look at them…”

That. Just. Brutal.

I can’t even imagine hearing this from the pulpit, and if it were directed toward me or my family, I can assure you that I would never darken the church door again.

We will never know the specifics, of course, although I certainly want details with names. Still, this reminds me of the outrage of the European colonizers when they discovered that many of the tribes in what became known as the Americas practiced a form of polygamy and had, successfully, for generations. It was their normal, and they saw no reason to change.

Extremely heated feelings and prejudice had existed prior to the Expulsion in 1755, at least as early as 1745, wherein the Acadian Lieutenant-Governor Paul Mascarene wrote, in part, that people in vessels from New England were pressing inhabitants of Annapolis Royal to “destroy all the inhabitants that had any Indian blood in them and scalp them…”

In other words, this sentiment was not restricted only to the Cape Sable region. Those seeds were planted before the Deportation and may have had roots more than a century earlier, especially if the Mi’kmaq did not completely reject their Native cultural ways and entirely assimilate into the French Catholic religious family. The only problem was, of course, that even if they did, they still looked Native, and they still had Native customs and relatives.

Four Acadian women in 1895 from the Argyle Township Courthouse Archives.

Even generations later, vestiges of an earlier culture were still present in their descendants. In terms of how they looked and dressed, their handwork, how they reacted to certain situations based on previous encounters, and resulting from generationally transmitted trauma in the sense of what their ancestors had survived – or didn’t.

While the priest was frustrated with the Mi’kmaq or mixed Acadian/Mi’kmaq culture, there was plenty of blame to go around.

In 1723, Philippe Mius’s son, François Mius, half-brother of our Françoise, along with some other Native people who were also related to our family, had been captured by the English from one of the coastal Native villages and were being held in Boston.

This scene with a Mi’kmaq father and son in 1871 at Tufts Cove probably looked much the same as the same scene a century or two earlier, except for the house and their clothes.

In 1726, several Native men, including Philippe Mius, were frustrated with the fact that despite a supposed peace treaty between the English, French, and Mi’kmaq, their family members hadn’t been returned. This led to an incident we’ll review in detail in a later article, where a group of men attempted to hold an English fishing vessel in exchange for the return of their family members. This led to charges of privacy wherein four of Philippe Mius’s family members, including two sons, his son-in-law, and his grandson were hung by the English as pirates.

Of course, François was half French, as were at least some of the other hostages taken in 1723, but were considered lesser citizens when classified as “Indians.” Even worse, the French informed the Mi’kmaq that there was no treaty with the English, encouraging and emboldening their actions against the English that were subsequently interpreted as piracy instead of warfare – which resulted in several hangings. The French and English both benefitted from the intimidation, but neither paid any price. The mixed Mi’kmaq/Acadian families suffered horribly.

It’s no wonder that trust was difficult to come by. Discrimination, however blatant or disguised, seems to have been baked into life in Acadia – at least if you were mixed Native. You fit in neither culture – so you created your own.

François Mius, Chief of the Mi’kmaq

At some point after his brothers were hung in 1726, François Mius was released as a hostage and returned to Acadia.

François, sometimes known as Francis, is further discussed by Christian Boudreau, Director, L’Association des AcadiensMetis-Souriquois, in his paper, News and Reflections: “A Further Exploration of the Life of Chief François Mius of La Hève and Mirliguesche, Acadia” dated August 3, 2019.

In 1742, François was mentioned in correspondence recorded at Louisbourg.

It is necessary for the good of the Service of his Majesty & for the tranquility of the Savage Mikmak village of Mirligueche in Acadia depending on this government, to provide for the establishment of a Chief whose experience for War & good conduct Be known, & Under the good & laudable relationship that has been made to us of the person named Francois Miouce of his capacity for War & of His Zeal & attachment to France. We did not believe we would make a better choice than His person to command the said village of Mirligueche; & in consequence it was committed & established by these presents to put him at the head of all of the Savages comprising the said village in order to make them carry out the orders that we will give him. Order to all of the said Savages to recognize him & obey him in everything he will command them for the Service of the King.

For the reason why We gave him the Presents, & to this one has the stamp of our Weapons affixed. Written at Louisbourg this twenty fifth of July one thousand seven hundred and forty two.

This document confirmed that it was the French who decided that François Miouce (Mius) was the best selection for chief due to his strong connections to France, and that he was living at Mirligueche, near Lunenburg. In other words, the French clearly exerted significant control and influence over the Mi’kmaq people.

NB: The Son of Said Francis Miouce, possessor of the original hath besides a medal of Louis XV, which he wears when he appears at Church or in publick. he is now in a decrepit old age.”

In 1812, Father Sigogne wrote that he:

“Went in a neighboring wood where I knew that Jacques Muice Son to Francis was laying infirm by old age. I demanded of him His Father’s Credential Letters, which he willingly delivered…”

The authors explain that this excerpt is important because it identifies:

“Jacques as the son of said Francis Miouce, possessor of the original hath besides a medal of Louis XV, which he wears when he appears at Church or in publick. he is now in a decrepit old age” that was mentioned by Père Jean-Mandé Sigogne in the “NB.” (Notez Bien) section of his copy of the recently-discussed “Brevet de Commission of the Indian chief.” Therefore, we can conclude that the son of Chief Franois Mius who had inherited this document, as well as the “medal of Louis XV” was named “Jacques Muice” (Jacques Mius).”

François and his family clearly cherished his medal, but he was also a practical man, cognizant of which way the wind was blowing.

In 1761, Francis Mius signed a friendship treaty with the English, signing for himself and as the chief of the tribe of the La Heve Indians. This occurred after the 1755-1758 deportation of the Acadians, so the mixed people living in the Native villages were not deported – but all other French or Acadians had been.

I’m sure the Mi’kmaq understood the danger clearly.

Francis is the anglicized version of François.

The only way to survive was to make peace with the English and agree to English law. The Mi’kmaq had no option. They had seen all too clearly what happened to those who refused to capitulate. This agreement included giving two Mi’kmaq hostages at Halifax to ensure good behavior as defined in the agreement. However, no English hostages were given in exchange.

Of course, this treaty was written in English. Initially, I wondered if François had any idea what he was signing – but then I remembered that he had been held hostage in Boston for at least three years. Of course, he understood at least rudimentary English, although he could neither read nor write, based on the fact that he made a mark for his signature.

This copy of the treaty at the Nova Scotia Archives was made in 1812 from an original that no longer exists. However, the original treaty apparently detailed a Peace-Dance and Ceremony of Burying War-Weapons. This event was recorded in a letter dated May 9, 1812, written by Sir John Coape Sherbrooke detailing what was related to him by “an Acadian eye-witness,” who was the friend of the interpreter. At this time, he was living at La Hève, Acadia.

“… At the conclusion of the Treaty, according to their Custom the Indians had their Peace-Dance and Ceremony of burying war-weapons. The Priest was present with some Acadians and many English people. A hole being dug, the chief at the head of his warriors began the dance with the Casse-Tête in their hands. They made more sounds that customary and the Chief shewed some reluctance. He had much talk that was not understood by the bye Standers but by the Priest who came nearer & whispered to the Chief to fling his Hatchet in the hole; The Chief observed that perhaps they would be oppressed and could not afterwards make war again. The Priest then told him that if any wrong were done them, they might take their arms again. Then the Indians flung down instantly their weapons, which were soon covered with the earth.”

Based on various treaties, letters and documents, Boudreau concludes that, “the descendants of Chief François Mius were considered to have been Mi’kmaq, whereas the descendants of his half-brother, the “Part Indian” Joseph Mius d’Azy I were considered to have been “Sang-Mêlés” (“Mixed-Bloods”)/Métis/“Bois-Brûlés (Burnt Woods)”/Etc. As we’ve seen at various points throughout this collection, other siblings of these two men (half- and full-siblings) and their descendants were labelled as “Mulattos,” “Demi-Sauvagesses,” etc.”

One final letter from Father Sigogne to John Cope Sherbrooke, also discussing the 1761 treaty and subsequent war-weapon burying ceremony reveals the identity of the Mi’kmaq Chief as Francis Mius and statrs that he had gone into the woods and spoken with his son, Jacques.

Furthermore, Father Sigogne wrote:

The kind and obliging reception by which your Excellency has been pleased to honour my Memorial & Petition in behalf of the Indians excites my most earnest thanks, and sincere zeal in behalf of these unfortunate beings. I shall be sparing, and I will not abuse of your Excellency’s generosity. Under your auspices I have a firm hope that something shall be done from government in regard to the purposes exposed in the Memorial. It is to be wished that the Legislature would take the Indians into some consideration and forbid the selling them strong liquours as it is done in Canada, I am told. That would prove the first step to render them useful members of Society. Indeed their degenerate condition renders any of them unfit to be chief, however some trial should be made to bring them to a better order. I have heard the best character of that old chief Franc. Miuce both for Morals and Religion, from every body that knew him, but his descendants do not follow his steps. His family, however poor, is respected amongst the Indians.

Françoise Mius’s Family

Françoise Mius’s family was inextricably interwoven with the Mi’kmaq people. Her half-brother, François was eventually chief of the tribe, so he was clearly considered Indian, as were his descendants. Her full brother Jacques was considered to be half-Native. Two of her half-brothers were hung in Boston in 1726 as “Indian” pirates. I wonder if their obvious mixed-race, aka non-white, status played any part in that and if they were hung to serve as an example.

One of Françoise’s half-sisters survived the Deportation and died in France, so she and her family were clearly considered “Acadian.”

Others simply disappeared, either as a function of death or an undocumented life among the Native people. Some may have survived the deportation by “disappearing into the woods.” No family would have been better prepared to do so.

Additional information about this family can be found here.

Given this history in the years before the 1755 Expulsion, and illustrated by those Acadians who returned to Cape Sable, it’s no wonder that others who were “mixed,” especially if they could pass as “white,” settled in a new home elsewhere.

That break with the homeland had already occurred in 1755, so after a decade in exile, it might have been best to put down roots somewhere else.

Honoré Lore/Lore, born in 1742, was only two generations from Françoise Mius, who was half Mi’kmaq, and whose family was widely known and associated with the Mi’kmaq. That made him one-eighth. In that place and time, percentages didn’t matter. It seems that Indian or not was a binary question – yes or no – and our family’s answer was unquestionably yes. Everyone in Acadia knew that.

While Françoise married Jacques Bonnevie, a newly-imported military Frenchman, her family was clearly still viewed as “Indian,” and her descendants would have been as well.

So, Honoré spent a forced decade in exile someplace in New York, fought in the Revolutionary War, and then made his way to Quebec, where he probably never mentioned his mixed-race heritage. Yes, other Acadians would have or could have known, but many of them were probably related to him as well. Maybe no one else said anything, either. Those horrific deportation memories were still burned into their collective memory, and they weren’t about to say one thing to anyone about something that even might cause them to be discriminated against again.

Nope, lips were sealed.

Yet, Honoré had an “old Indian quilt” in his estate when he died in 1818. Perhaps this was his connection to old Acadia, and to Françoise, the grandmother he had never known. To his people, the Mi’kmaq, whose heritage he had lost when expelled. Did he hold it close in times of great peril, and did it protect and warm him as she could not do?

Based on the blending of cultures and traditions, this group of intermarried and endogamous families formed a unique subculture, distinct from the other Acadian families, and from the unmixed Mi’kmaq. They had feet firmly planted in both worlds – Native and French – a condition that did not endear them to the English, who were always nipping around the edges and eventually succeeded in displacing the French.

While we sometimes find Native American haplogroups among the Acadians, including the confusing Germain Doucet born in 1641, we can also expect to find European haplogroups among the descendants of the Native people.

Genevieve Massignon, who researched in the mid-1900s, came to the conclusion that the “Mius d’Entremont left many illegitimate children in different parts of Acadia.” Again, “illegitimate” is a European construct. He noted that “the strain of Indian blood is still visible,” which I interpret to mean that Native features were still evident among the families in Yarmouth, Tusket, and Belleville, near Pubnico.

This 1935 photo shows “Birch-bark summer ‘camp’ or wigwam of Micmac Indian, Henry Sack (son of Isaac Sack) and his wife Susan (in typical old Micmac woman’s costume) on Indian Point, Fox Point Road, near Hubbards, Lun. Co., N.S. Left to right: Susan Sack, Harry Piers of Halifax, and Henry Sack of Indian reservation, Truro, N.S. View looking northeast…Carrying basket made by Henry Sack.” Photo courtesy of the Nova Scotia Archives.

In 1644, Charles d’Aulnay wrote that in 1624:

“The men ran the wood with 18 or 20 men, mixed with the savages and lived a libertine life, and infamous as crude beasts without exercise of religion and similarly not having the care to baptize the children procreated by them and these poor miserable women. On the contrary, they abandoned them to their mothers as at present they do during which time the English usurp the whole extend of New France and on the said Coasts of Acadia.”

According to the authorities, such as they were, those men were having just too much fun and liberty. They adopted the Native lifestyle, not vice versa. That lifestyle persisted, at least in part, before, through, and after the deportation.

It was also recorded that La Tour had fathered mixed children, some of whom were daughters who took his surname.

Given the circumstances surrounding our Françoise’s birth with Philippe Mius II marrying into and residing among the Mi’kmaq, we really don’t know who her mother was. It’s possible that she did not share the same mother as the other Mius children. Hopefully, additional mitochondrial DNA testing of people descended from Philippe Mius’s female children (through all females) will determine how many women were mothers to his children. I expect Francoise’s descendants will match the descendants of the older set of children. Philippe was never known to have married or fathered children outside of the Mi’kmaq tribe.

Lastly, it’s interesting that the R vs. Powley Canadian Supreme Court case in 2003 surfaced many earlier historical writings that had been buried deep in archives, along with writings of earlier authors.

One author, John MacLean, wrote in 1996 that Acadian itself was a Native language, different from French, having evolved over 350 years. Of course, the Mi’kmaq cultural influence, especially among mixed families, would have influenced the Acadian language as well.

Another author, in Daniels vs Canada in 2016, noted that as early as 1650, a separate and distinct Metis community had developed in Le Heve, separate from Acadians and Mi’kmaq Indians. Of course, that’s where our Mius family is found.

I want to close this section by saying that it’s important to understand our heritage, our genesis, and the social and cultural environments that our ancestors thrived in, along with situations that they simply endured and survived.

I’m heartbroken to learn that discrimination, especially of this magnitude, existed. I had no idea. But my heart swells with pride at the endurance and tenacity of my ancestors. They did survive. Sometimes against unimaginable odds with factors far outside their control.

Viva the Great Spirit of the Mi’kmaq, the Metis, Sang-Mêlés and Bois-Brûlé by whatever name! Their blood runs in me, and I am proud of them!

About that Mi’kmaq DNA

My mother and I carry a segment of Native American DNA that is traceable back through the ancestral lines to Françoise and, therefore, her mother.

My mother and I both share this same pink Native American segment of DNA on chromosome 1, identified at both 23andMe and FamilyTreeDNA.

I copied the segment information to DNAPainter, along with other matches to people on that same segment whose ancestors I can identify.

DNAPainter “stacks” match on your chromosomes. These maternal matches align with those Native American segments.

The green match shares ancestor Antoine, aka, Anthony Lore with me.

Other individuals share ancestors further back in the tree.

Using those shared Native ethnicity segments, matches with shared ancestors, DNAPainter to combine them, and mitochondrial DNA testing to prove that Françoise mother was indeed Native – I was able to prove that I do, in fact, carry (at least) one DNA segment from Françoise Mius’s mother.

Even though the Acadian and Native heritage had been forgotten (or hidden) in my family, DNA didn’t forget, and Françoise lived on, just waiting to be found.

How cool is this??!!!

But there’s still one unanswered question.

What Happened to Françoise Mius?

Don’t I wish we knew?

Françoise Mius’s children’s baptisms were recorded in Port Royal beginning in 1704. Her children were married there as well, beginning in 1718 when her namesake daughter, Françoise, married.

The last record we have indicating that Françoise was alive was the baptism of Charlies in 1715. For that matter, we don’t have any further records for Charles either.

In 1715, Françoise would have only been about 31 years of age. The fact that we find no additional baptisms also strongly suggests she died about that time – sometime between 1715 and 1717, when the next child would be expected.

One would think that if Françoise were still alive, she would appear at least once in her grandchildren’s baptism records, but she doesn’t.

Both Françoise and her father, Philippe Mius, were clearly Catholic.

It’s important to note that while we have birth and baptism records for 1715, there are no extant death records for that year. The first death record after the 1715 baptism didn’t appear until November of 1720, so it’s very likely that Françoise and Charles both died during that time.

In fact, it’s possible that they both died shortly after his birth and are buried together in an unmarked and unremembered grave near where the Catholic church once stood in Annapolis Royal.

_____________________________________________________________

Follow DNAexplain on Facebook, here.

Share the Love!

You’re always welcome to forward articles or links to friends and share on social media.

If you haven’t already subscribed (it’s free,) you can receive an e-mail whenever I publish by clicking the “follow” button on the main blog page, here.

You Can Help Keep This Blog Free

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase your price but helps me keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Uploads

Genealogy Products and Services

My Book

Genealogy Books

Genealogy Research

Like this:

Like Loading...