The introduction of the Phased Family Finder Matches has added a new way to view autosomal DNA results at Family Tree DNA and a powerful new tool to the genealogists toolbox.

The Phased Family Finder Matches are the 9th tool provided for autosomal test results by Family Tree DNA. Did you know where were 9?

Each of the different methodologies provides us with information in a unique way to assist in our relentless search for cousins, ancestors and our quests to break down brick walls.

That’s the good news.

The not-so-good news is that sometimes options are confusing, so I’d like to review each tool for viewing autosomal match information, including:

- When to use each tool

- How to use each tool

- What the results mean to you

- The unique benefits of each tool

- The cautions and things you need to know about each tool including what they are not

The tools are:

- Regular Matching

- ICW (In Common With)

- Not ICW (Not In Common With)

- The Matrix

- Chromosome Browser

- Phased Family Matching

- Combined Advanced Matching

- MyOrigins Matching

- Spreadsheet Matching

You Have Options

Family Tree DNA provides their clients with options, for which I am eternally grateful. I don’t want any company deciding for me which matches are and are not important based on population phasing (as opposed to parental phasing), and then removing matches they feel are unimportant. For people who are not fully endogamous, but have endogamous lines, matches to those lines, which are valid matches, tend to get stripped away when a company employs population based phasing – and once those matches are gone, there is no recovery unless your match happens to transfer their results to either Family Tree DNA or GedMatch.

The great news is that the latest new option, Phased Family Matching, is focused on making easy visual comparisons of high quality parental matches which is especially useful for those who don’t want to dig deeply.

There are good options for everyone at all ranges of expertise, from beginners to those who like to work with spreadsheets and extract every teensy bit of information.

So let’s take a look at all of your matching options at Family Tree DNA. If you’re not taking advantage of all of them, you’re missing out. Each option is unique and offers something the other options don’t offer.

In case you’re curious, I’ll be bouncing back and forth between my kit, my mother’s kit and another family member’s kit because, based on their matches utilizing the various tools, different kits illustrate different points better.

Also, please note that you can click on any image to see a larger version.

Selecting Options

Your selection options for Family Finder are available on both your Dashboard page under the Family Finder heading, right in the middle of the page, and the dropdown myFTDNA menu, on the upper left, also under Family Finder.

Ok, let’s get started.

#1 – Regular Matching

By regular matching, I’m referring to the matches you see when you click on the “Matches” tab on your main screen under Family Finder or in the dropdown box.

Everyone uses this tool, but not everyone knows about the finer points of various options provided.

There’s a lot of information here folks. Are you systematically using this information to its full advantage?

Your matches are displayed in the highest match first order. All of the information we utilize regularly (or should) is present, including:

- Relationship Range

- Match Date

- Shared CentiMorgans

- Longest (shared) Block

- X-Match

- Known Relationship

- Ancestral Surnames (double click to see entire list)

- Notes

- E-mail envelope icon

- Family Tree

- Parental “side” icon

The Expansion “+” at the right side of each match, shown below, shows us:

- Tests Taken

- mtDNA haplogroup

- Y haplogroup

Clicking on your match’s profile (their picture) provides additional information, if they have provided that information:

- Most distant maternal ancestor

- Most distant paternal ancestor

- Additional information in the “about me” field, sometimes including a website link

On the match page, you can search for matches either by their full name, first name, last name or click on the “Advanced Search” to search for ancestral surname. These search boxes can be found at the top right.

The Advanced Search feature, underneath the search boxes at right, also provides you with the option of combining search criteria, by opening two drop down boxes at the top left of the screen.

Let’s say I want to see all of my matches on the X chromosome. I make that selection and the only people displayed as matches are those whom I match on the X chromosome.

You can see that in this case, there are 280 matches. If I have any Phased Family Matches, then you will see how many X matches I have on those tabs too.

The first selection box works in combination with the second selection box.

Now, let’s say I want to sort in Longest Block Order. That section sorts and displays the people who match me on the X chromosome in Longest Block Order.

Prerequisites

- Take the Family Finder test or transfer your results from either 23andMe (V3 only) or Ancestry (V1 only, currently.)

- Match must be over the matching threshold of 9cM if shared cM are less than 20, or, the longest block must be at least 7.69 cM if the total shared cM is 20 or greater.

Power Features

- The ability to customize your view by combining search, match and sort criteria.

Cautions

- It’s easy to forget that you’re ONLY working with X matches, for example, once you sort, and not all of your matches. Note the Reset Filter button above your matches which clears all of the sort and search criteria. Always reset, just to be on the safe side, before you initiate another sort.

- Please note that the search boxes and logic are in the process of being redesigned, per a conversation Michael Davila, Director of Product Development, on 7-20-2016. Currently, if you search for the name “Donald,” for example, and then do an “in common with” match to someone on the Donald match list, you’ll only see those individuals who are in common with “Donald,” meaning anyone without “Donald” as one of their names won’t show as a match. The logic will be revised shortly so that you will see everyone “in common with,” not just “Donald.” Just be aware of this today and don’t do an ICW with someone you’ve searched for in the search box until this is revised.

#2 – In Common With (ICW)

You can select anyone from your match list to see who you match in common with them.

This is an important feature because it gives me a very good clue as to who else may match me on that same genealogical line.

For example, cousin Donald is related on the paternal line. I can select Donald by clicking the box to the left of his profile which highlights his row in yellow. I can then select what I want to do with Don’s match.

You will see that Don is selected in the match selection box on the lower left, and the options for what I can do with Don are above the matches. Those options are:

- Chromosome Browser

- In Common With

- Not in Common With

Let’s select “In Common With.”

Now, the matches displayed will ONLY be those that I match in common with Don, meaning that Donald and I both match these people.

As you can see, I’m displaying my matches in common with Don in longest block order. You can click on any of the header columns to display in reverse order.

There are a total of 82 matches in common with Don and of those, 50 are paternally assigned. We’ll talk about how parental “side” assignments happen in a minute.

Prerequisites

- None

Power Features

- Can see at a glance which matches warrant further inspection and may (or may not) be from a common genealogical line.

Cautions

- An ICW match does NOT mean that the matching individual IS from the same common line – only genealogical research can provide that information.

- An ICW matches does NOT mean that these three people, you, your match and someone who matches both of you is triangulated – meaning matching on the same segment. Only individual matching with each other provides that information.

- It’s easy to forget that you’re not working with your entire match list, but a subset. You can see that Donald’s name appears in the box at the upper left, along with the function you performed (ICW) and the display order if you’ve selected any options from the second box.

# 3 – Not In Common With

Now, let’s say I want to see all of my X matches that are not in common with my mother, who is in the data base, which of course suggests that they are either on my father’s side or identical by chance. My father is not in the data base, and given that he died in 1963, there is no chance of testing him.

Keep in mind though that because X matches aren’t displayed unless you have another qualifying autosomal segment, that they are more likely to be valid matches than if they were displayed without another matching segment that qualifies as a match.

For those who don’t know, X matches have a unique inheritance pattern which can yield great clues as to which side of your tree (if you’re a male), and which ancestors on various sides of your tree X matches MUST come from (males and females both.) I wrote about this here, along with some tools to help you work with X matches.

To utilize the “Not In Common With” feature, I would select my mother and then select the “Not In Common With” option, above the matches.

I would then sort the results to see the X matches by clicking on the top of the column for X-Match – or by any other column that I wanted to see.

I have one very interesting not in common with match – and that’s with a Miller male that I would have assumed, based on the surname, was a match from my mother’s side. He’s obviously not, at least based on that X match. No assuming allowed!

Prerequisites

- None

Power Features

- Can see at a glance which matches warrant further inspection and may be from a common genealogical line – or are NOT in common with a particular person.

Cautions

- Be sure to understand that “not in common with” means that you, the person you match and the list of people shown as a result of the “Not ICW” do not all match each other. You DO match the person on your match list, but the list of “not in common with” matches are the people who DON’T match both of you. Not in common with is the opposite of “in common with” where your match list does match you and the person you’re matching in common with.

- The X and other chromosome matches may be inherited from different ancestors. Every matching segment needs to be analyzed separately.

#4 – The Matrix

Let’s say that I have a list of matches, perhaps a list of individuals that I found doing an ICW with my cousin, and I wonder if these people match each other. I can utilize the Matrix grid to see.

Going back to the ICW list with cousin Donald, let’s see if some of those people match each other on the Matrix.

Let’s pick 5 people.

I’m selecting Cheryl, Rex, Charles, Doug and Harold.

I’m making these particular selections because I know that all of these people, except Harold, are related to my mother, Barbara, shown on the bottom row of the chart above. This chart, borrowed from another article (William is not in this comparison), shows how Cheryl, Rex, Charles and Barbara who have all DNA tested are related to each other. Some are related through the Miller line, some through the dual Lentz/Miller line, and some just from the Lentz line. Doug is related through the Miller line only, and at least 4 generations upstream. Doug may also be related through multiple lines, but is not descended from the Lentz line.

The people I’ve selected for the matrix are not all related to each other, and they don’t all share one common ancestral line.

Harold is a wild card – I have no idea how he is related or who he is related to, so let’s see what we can determine.

As you make selections on the Matrix page, up to 10 selections are added to the grid.

You can see that Charles matches Cheryl and Harold.

You can see that Rex matches Charles and Cheryl and Harold.

You can see that Doug matches only Cheryl, but this isn’t surprising as the common line between Doug and the known cousins is at least 4 generations further back in time on the Miller line.

The known relationship are:

- Don and Cheryl are siblings, descended from the Lentz/Miller.

- Rex is a known cousin on the Miller/Lentz line

- Charles is a known cousin on the Lentz line only

- Doug is a known cousin on the Miller line only

Let me tell you what these matches indicate to me.

Given that Harold matches Rex and Charles and Cheryl, IF and that’s a very big IF, he descends from the same lines, then he would be related to both sides of this family, meaning both the Miller and Lentz lines.

- He could be a downstream cousin after the Lentz and Miller lines married, meaning a descendant of Margaret Lentz and John David Miller, or other Miller/Lentz couples

- He could be independently related to both lines upstream. They did intermarry.

- He could be related to Charles or Rex through an entirely separate line that has nothing to do with Lentz or Miller.

So I have no exact answer, but this does tell me where to look. Maybe I could find additional known Lentz or Miller line descendants to add to the Matrix which would provide additional information.

Prerequisites

- None

Power Features

- Can see at a glance which matches match each other as well.

Cautions

- Matrix matches do NOT mean that these individuals match on the same segments, it just means they do match on some segment. A matrix match is not triangulation.

- Matrix matches can easily be from different lines to different ancestors. For example, Harold could match each one of three individuals that he matches on different ancestral lines that have nothing to do with their common Lentz or Miller line.

#5 – Chromosome Browser

I want to know if the 5 individuals that I selected to compare in the Matrix match me on any of the same segments.

I’m going back to my ICW list with cousin Donald.

I’ve selected my 5 individuals by clicking the box to the left of their profiles, and I’m going to select the chromosome browser.

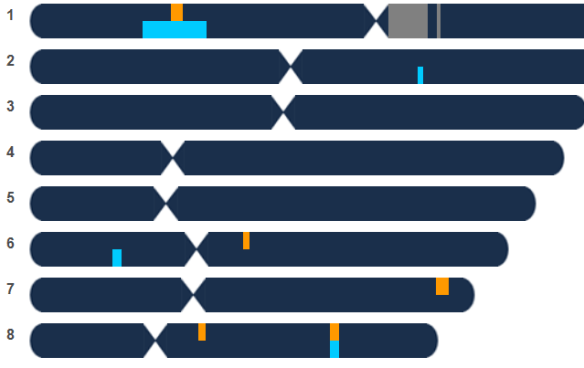

The chromosome browser shows you where these individuals match you.

Overlapping segments mean the people who overlap all match you on that segment, but overlapping segments do NOT mean they also match each other on these same segments.

Translated, this means they could be matching you on different sides of your family or are identical by chance. Remember, you have two sides to your chromosome, a Mom’s side and a Dad’s side, which are intermingled, and some people will match you by chance. You can read more about this here.

The chromosome browser shows you THAT they match you – it doesn’t tell you HOW they match you or if they match each other.

The default view shows matches of 5cM or greater. You can select different thresholds at the top of the comparison list.

You’ll notice that all 5 of these people match me, but that only two of them match me on overlapping segments, on chromosome 3. Among those 5 people, only those who match me on the same segments have the opportunity to triangulate.

This gives you the opportunity to ask those two individuals if they also match each other on this same chromosome. In this case, I have access to both of those kits, and I can tell you that they do match each other on those segments, so they do triangulate mathematically. Since I know the common ancestor between myself, Cheryl and Rex, I can assign this segment to John David Miller and Margaret Lentz. That, of course, is the goal of autosomal matching – to identify the common ancestor of the individuals who match.

You also have the option to download the results of this chromosome browser match into a spreadsheet. That’s the left-most download option at the top of the chromosomes. We’ll talk about how to utilize spreadsheets last.

The middle option, “view in a table” shows you these results, one pair of individuals at a time, in a table.

This is me compared to Rex. You will have a separate table for each one of the individuals as compared to you. You switch between them at the bottom right.

The last download option at the furthest right is for your entire list of matches and where they match you on your chromosomes.

Prerequisites

- None

Power Features

- Can visually see where individuals and multiple people match you on your chromosomes, and where they overlap which suggests they may triangulate.

Cautions

- When two people match you on the same chromosome segment, this does not mean that they also match each other on that segment. Matching on overlapping segments is not triangulation, although it’s the first step to triangulation.

- For triangulation, you will need to contact your matches to determine if they also match each other on the same segment where they both match you. You may also be able to deduce some family matching based on other known individuals from the same line that you also match on that same segment, if your match matches them on that segment too.

- The chromosome browser is limited to 5 people at a time, compared to you. By utilizing spreadsheet matching, you can see all of your matches on a particular segment, together.

#6 – Phased Family Matching

Phased Family Matching is the newest tool introduced by Family Tree DNA. I wrote about it here. The icons assigned to matches make it easy to see at a glance which side of your family, maternal or paternal, or both, a match derives from.

![]() Phased Family Matching allows you to link the DNA results of qualified relatives to your tree and by doing so, Family Tree DNA assigns matches to maternal or paternal buckets, or sometimes, both, as shown in the icon above.

Phased Family Matching allows you to link the DNA results of qualified relatives to your tree and by doing so, Family Tree DNA assigns matches to maternal or paternal buckets, or sometimes, both, as shown in the icon above.

This phased matching utilizes both parental phasing in addition to a slightly higher threshold to assure that the matches they assign to parental sides can be done so with confidence. In order to be assigned a maternal or paternal icon, your match must match you and your qualifying relative at 9cM or greater on at least one of the same segments over the matching threshold. This is different than an ICW match, which only tells you that you do match, not how you match or that it’s on the same segment.

Qualifying relatives, at this time, are parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts and first cousins. Additional relatives are planned in the near future.

Icons are ONLY placed based on phased match results that meet the criteria.

These icons are important because they indicate which side of your family a match is from with a great deal of precision and confidence – beyond that of regular matching.

This is best illustrated by an example.

In this example, this individual has their father and mother both in the system. You can see that their father’s side is assigned a blue icon and their mother’s side is assigned a pink (red) icon. This means they match this person on only one side of their family. A purple icon with both a male and female image means that this person is related to you on both sides of your family. Full siblings, when both parents are in the system to phase against, would receive both icons.

This sibling is showing as matching them on both sides of their family, because both parents are available for phasing.

If only one parent was available, the father, for example, then the sibling would only shows the paternal icon. The maternal icon is NOT added by inference. In Phased Family Matching, nothing is added by inference – only by exact allele by allele matching on the same segment – which is the definition of parentally phased matching.

These icons are ONLY added as a result of a high quality phased matches at or above the phased match threshold of 9cM.

You can read more about the Family Matching System in the Family Tree DNA Learning Center, here.

Prerequisites

- You must have tested (or transferred a kit) for a qualifying relative. At this time qualifying relatives parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles and first cousins.

- You must have uploaded a GEDCOM file or created a tree.

- You must link the DNA of qualifying kits to that person your tree. I provided instructions for how to do this in this article.

- You must match at the normal matching threshold to be on the match list, AND then match at or above the Phased Family Match threshold in the way described to be assigned an icon.

- You must match on at least one full segment at or above 9cM.

Power Features

- Can visually see which side of your family an individual is related to. You can be confident this match is by descent because they are phased to your parent or qualifying family member.

Cautions

- If someone does not have an icon assigned, it does NOT mean they are not related on that particular side of the family. It only means that the match is not strong enough to generate an icon.

- If someone DOES match on a particular side of the family, you will still need to do additional matching and genealogy work to determine which ancestor they descend from.

- If someone is assigned to one side of your family, it does NOT preclude the possibility that they have a smaller or weaker match to your other side of the family.

- If you upload a new Gedcom file after linking DNA to people in your tree, you will overwrite your DNA links and will have to relink individuals.

- Having an icon assigned indicates mathematical triangulation for the person who tested, their parents or close relative against whom they were phased and their match with the icon. However, technically, it’s not triangulation in cases where very close relatives are involved. For example, parents, aunts, uncles and siblings are too closely related to be considered the third leg of the triangulation stool. First cousins, however, in my opinion, could be considered the third leg of the three needed for triangulation. Of course when triangulation is involved, more than three is always better – the more the merrier and the more certain you can be that you have identified the correct ancestor, ancestral couple, or ancestral line to assign that particular triangulated segment to.

# 7 – Combined Advanced Matching

One of the comparison tools often missed by people is Combined Advanced Matching.

Combined matching is available through the “Tools and Apps” button, then select “Advanced Matching.”

Advanced Matching allows you to select various options in combination with each other.

For example, one of my favorites is to compare people within a project.

You can do this a number of ways.

In the case of my mother, I’ll select everyone she matches on the Family Finder test in the Miller-Brethren project. This is a very focused project with the goal of sorting the Miller families who were of the Brethren faith.

You can see that she has several matches in that project.

You can select a variety of combinations, including any level of Y or mtDNA testing, Family Finder, X matching, projects and “last name begins with.”

One of the ways I utilize this feature often is within a surname project, for males in particular, I select one Y level of matching at a time, combined with Family Finder, “show only people I match on all tests” and then the project name. This is a quick way to determine whether someone matches someone on Family Finder that is also in a particular surname project. And when your surname is Smith, this tool is extremely valuable. This provides a least a hint as to the possible distance to a common ancestor between individuals.

Another favorite way to utilize this feature is for non-surname projects like the American Indian project. This is perfect for people who are hunting for others with Native roots that they match – and you can see their Y and mtDNA haplogroups as a bonus!

Prerequisites

- Must have joined the particular project if you want to use the project match feature within that project.

Power Features

- The ability to combine matching criteria across products.

- The ability to match within projects.

- The ability to specify partial surnames.

Cautions

- If you match someone on both Family Finder and either Y or mtDNA haplogroups, this does NOT mean that your common Family Finder ancestor is on that haplogroup line. It might be a good place to begin looking. Check to see if you match on the Y or mtDNA products as well.

- All matches have their haplogroup displayed, not just IF you also match that haplogroup, unless you’ve specified the Y or mtDNA options and then you would only see the people you match which would be in the same major haplogroup, although not always the same subgroup because not everyone tests at the same level.

- Not all surname project administrators allow people who do not carry that surname in the present generation to join their projects.

# 8 – MyOrigins Matching

One tool missed by many is the MyOrigins matching by ethnicity. For many, especially if you have all European, for example, this tool isn’t terribly useful, but if you are of mixed heritage, this tool can be a wonderful source of information.

Your matches (who have authorized this type of matching) will be displayed, showing only if they match you on your major world categories. Only your matching categories will show. For example, if my match, Frances, also has African heritage and I do not, I won’t see Frances’s African percentage and vice versa.

In this example, the person who tested falls into the major categories of European and Middle Eastern. Their matches who fall into either of these same categories will be displayed in the Shared Origins box. You may not be terribly excited about this – unless you are mixed African, Asian, European and Native American – and you have “lost ancestors” you can’t find. In that case, you may be very excited to contact other matches with the same ethnic heritage.

When you first open your myOrigins page, you will be greeted with a choice to opt in (by clicking) or to opt out (by doing nothing) of allowing your ethnic matches to view the same ethnic groups you carry. Your matches will not be able to see your ethnic groups that they don’t have in common with you.

You can also access those options to view or change by clicking on Account Settings, Privacy and Sharing, and then you can view or change your selection under “My DNA Results.”

Prerequisites

- Must authorize Shared Origins matching.

Power Features

- The ability to discern who among your matches shares a particular ethnicity, and to what degree.

Cautions

- Just because you share a particular ethnicity does NOT mean you match on the shared ethnic line. Your common ancestor with that person may be on an entirely unrelated line.

# 9 – Spreadsheet Matching

Family Tree DNA offers you the ability to download your entire list of matches, including the specific segments where your matches match you, to a spreadsheet.

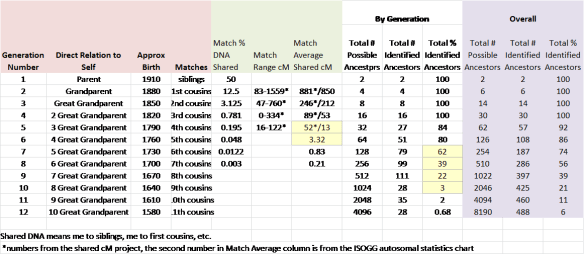

This is the granddaddy of the tools and it’s a tool used by all serious genetic genealogists. It’s requires the most investment from you both in terms of understanding and work, but it also yields the most information.

The power of spreadsheet comparisons isn’t in the 5 people I pushed through to the chromosome browser, in and of themselves, but in the power of looking at the locations where all of your matches match you and known relatives on particular segments.

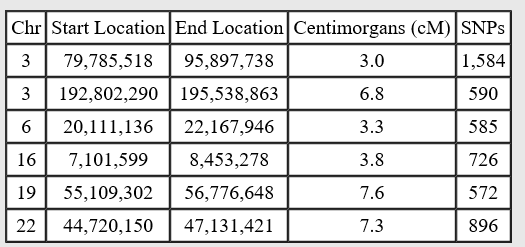

Utilizing the chromosome browser, we saw that chromosome 3 had an overlap match between Rex (green) and Cheryl (blue) as compared to my mother (background chromosome.)

We see that same overlap between Cheryl and Rex when we download the match spreadsheet for those 5 people.

However, when we download all of my mother’s matches, we have a much more powerful view of that segment, below. The 2 segments we saw overlapping on the chromosome browser are shown in green. All of these people colored pink match my mother on some part of the 37cM segment she shares with Rex.

This small part of my master spreadsheet combines my own results, rows in white, with those of my mother, rows in pink.

In this case, I only match one of these individuals that mother also matches on the same segment – Rex. That’s fine. It just means that I didn’t receive the rest of that DNA from mother – meaning the portions of the segments that match Sam, Cheryl, Don, Christina and Sharon.

On the first two rows, I did receive part of that DNA from mother, 7.64 of the 37cMs that Rex matches to Mom at a threshold of 5cM.

We know that Cheryl, Don and Rex all share a common ancestor on mother’s father’s side three generations removed – meaning John David Miller and Margaret Lentz. By looking at Cheryl, Don and Rex’s matches as well, I know that several of her matches do triangulate with Cheryl, Don and/or Rex.

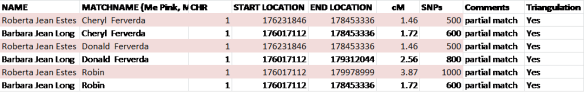

What I didn’t know was how Christina fit into the picture. She is a new match. Before the new Phased Family Matching, I would have had to go into each account, those of Rex, Cheryl and Don, all of which I manage, to be sure that Christina matched all of them individually in addition to Mom’s kit.

I don’t have to do that now, because I can utilize the phased Family Matching instead. The addition of the Family Matching tool has taken this from three additional steps, assuming I have access to all kits, which most people don’t, to one quick definitive step.

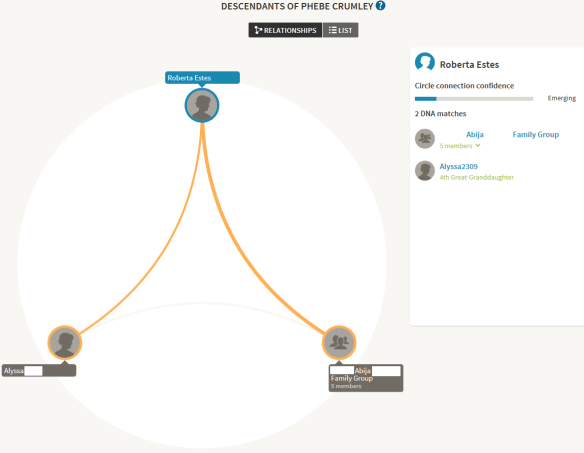

Cheryl and Don are both mother’s first cousins, so matches can be phased against them. I have linked both of them to mother’s kit so she how has several individuals who are phased to Don and Cheryl which generate paternal icons since Don and Cheryl are related to mother on her father’s side.

Now, instead of looking at all of the accounts individually, my first step is to see if Christina has a paternal icon, which, in this case, means she phased against either Don and/or Cheryl since those are the only two people linked to mother who qualify for phasing, today.

Look, Christina does have a paternal icon, so I can add “Dad” into the side column for Christine in the spreadsheet for mother’s matches AND I know Christina triangulates to Mom and either Cheryl or Don, which ever cousin she phased against.

I can see which cousin she phased against by looking at the chromosome browser and comparing mother against Cheryl, Don and Christina. As it turns out, Christina, in green, above, phased against both Cheryl and Don whose results are in orange and blue.

It’s a great day in the neighborhood to be able to use these tools together.

Prerequisites

- Must download matches spreadsheet through the chromosome browser, adding new matches to your spreadsheet as they occur.

- Must have a familiarity with Excel or another spreadsheet.

- Must learn about matching, match groups and triangulation.

Power Features

- The ability to control the threshold you wish to work with. For matches over the match threshold, Family Tree DNA provides all segment matches to 1cM with a total of 500 SNPs.

- The ability to see trends and groups together.

- The ability to view kits from all of your matches for more powerful matching.

- The ability to combine your results with those of a parent (or sibling if parents not available) to see joint matching where it occurs.

Cautions

- There is a comparatively steep learning curve if you’re not familiar with using spreadsheets, but it’s well worth the effort if you are serious about proving ancestors through triangulation.

Summary

I’m extremely grateful for the full complement of tools available at Family Tree DNA.

They provide a range of solutions for users at all levels – people who just want to view their ethnicity or to utilize matches at the vendor site as well as those who want tools like a chromosome browser, projects, ICW, not ICW, the Matrix, ethnicity matching, combined advanced matching and chromosome browser downloads for those of us who want actual irrefutable proof. No one has to use the more advanced tools, but they are there for those of us who want to utilize them.

I’m sorry, I’m not from Missouri, but I still want to see it for myself. I don’t want any vendor taking the “trust me” approach or doing me any favors by stripping out my data. I’m glad that Family Tree DNA gives us multiple options and doesn’t make one size fit all by using a large hammer and chisel.

The easier, more flexible and informative Family Tree DNA makes the tools, the easier it will be to convince people to test or download their data from other vendors. The more testers, the better our opportunity to find those elusive matches and through them, ancestors.

The Concepts Series

I’ve been writing a “Concepts” series of articles. Recent articles have been about how to utilize and work with autosomal matches on a spreadsheet.

You might want to read these Concepts articles if you’re serious about working with autosomal DNA.

Concepts – How Your Autosomal DNA Identifies Your Ancestors

Concepts – Identical by…Descent, State, Population and Chance

Concepts – CentiMorgans, SNPs and Pickin’ Crab

Concepts – Downloading Autosomal Data from Family Tree DNA

Concepts – Managing Autosomal DNA Matches – Step 1 – Assigning Parental Sides

Please join me shortly for the next Concepts article – Step 2 – Who’s Related to Whom?

In the meantime:

- Make full use of the autosomal tools available at Family Tree DNA.

- Test additional relatives meaning parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, half-siblings, siblings, any cousin you can identify and talk into testing.

- Take test kits to family reunions and holiday gatherings. No, I’m not kidding.

- Don’t forget Y or mtDNA which can provide valuable tools to identify which line you might have in common, or to quickly eliminate some lines that you don’t have in common. Some cousins will carry valuable Y or mtDNA of your direct ancestral lines – and that DNA is full of valuable and unique information as well.

- Link the DNA kits of those individuals you know to their place in your tree.

- Transfer family kits from other vendors.

The more relatives you can identify and link in the system, the better your chances for meaningful matches, confirming ancestral relations, and solving puzzles.

Have fun!!!

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- Family Tree DNA

- MyHeritage DNA only

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload

- AncestryDNA

- 23andMe Ancestry

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists for genealogy research