There has been a lot of discussion lately, and I mean REALLY a lot, about chromosome browsers, the need or lack thereof, why, and what the information really means.

For the old timers in the field, we know the story, the reasons, and the backstory, but a lot of people don’t. Not only are they only getting pieces of the puzzle, they’re confused about why there even is a puzzle. I’ve been receiving very basic questions about this topic, so I thought I’d write an article about chromosome browsers, what they do for us, why we need them, how we use them and the three vendors, 23andMe, Ancestry and Family Tree DNA, who offer autosomal DNA products that provide a participant matching data base.

The Autosomal Goal

Autosomal DNA, which tests the part of your DNA that recombines between parents every generation, is utilized in genetic genealogy to do a couple of things.

- To confirm your connection to a specific ancestor through matches to other descendants.

- To break down genealogy brick walls.

- Determine ethnicity percentages which is not the topic of this article.

The same methodology is used for items 1 and 2.

In essence, to confirm that you share a common ancestor with someone, you need to either:

- Be a close relative – meaning you tested your mother and/or father and you match as expected. Or, you tested another known relative, like a first cousin, for example, and you also match as expected. These known relationships and matches become important in confirming or eliminating other matches and in mapping your own chromosomes to specific ancestors.

- A triangulated match to at least two others who share the same distant ancestor. This happens when you match other people whose tree indicates that you share a common ancestor, but they are not previously known to you as family.

Triangulation is the only way you can prove that you do indeed share a common ancestor with someone not previously identified as family.

In essence, triangulation is the process by which you match people who match you genetically with common ancestors through their pedigree charts. I wrote about the process in this article “Triangulation for Autosomal DNA.”

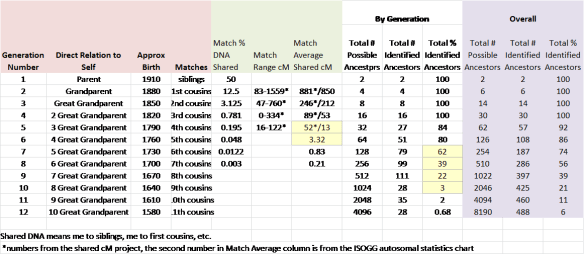

To prove that you share a common ancestor with another individual, the DNA of three proven descendants of that common ancestor must match at the same location. I should add a little * to this and the small print would say, “ on relatively large segments.” That little * is rather controversial, and we’ll talk about that in a little bit. This leads us to the next step, which is if you’re a fourth person, and you match all three of those other people on that same segment, then you too share that common ancestor. This is the process by which adoptees and those who are searching for the identity of a parent work through their matches to work forward in time from common ancestors to, hopefully, identify candidates for individuals who could be their parents.

Why do we need to do this? Isn’t just matching our DNA and seeing a common ancestor in a pedigree chart with one person enough? No, it isn’t. I recently wrote about a situation where I had a match with someone and discovered that even though we didn’t know it, and still don’t know exactly how, we unquestionably share two different ancestral lines.

When you look at someone’s pedigree chart, you may see immediately that you share more than one ancestral line. Your shared DNA could come from either line, both lines, or neither line – meaning from an unidentified common ancestor. In genealogy parlance, those are known as brick walls!

Blaine Bettinger wrote about this scenario in his now classic article, “Everyone Has Two Family Trees – A Genealogical Tree and a Genetic Tree.”

Proving a Match

The only way to prove that you actually do share a genealogy relative with someone that is not a known family member is to triangulate. This means searching other matches with the same ancestral surname, preferably finding someone with the same proven ancestral tree, and confirming that the three of you not only share matching DNA, but all three share the same matching DNA segments. This means that you share the same ancestor.

Triangulation itself is a two-step process followed by a third step of mapping your own DNA so that you know where various segments came from. The first two triangulation steps are discovering that you match other people on a common segment(s) and then determining if the matches also match each other on those same segments.

Both Family Tree DNA and 23andMe, as vendors have provided ways to do most of this. www.gedmatch.com and www.dnagedcom.com both augment the vendor offerings. Ancestry provides no tools of this type – which is, of course, what has precipitated the chromosome browser war.

Let’s look at how the vendors products work in actual practice.

Family Tree DNA

1. Chromosome browser – do they match you?

Family Tree DNA makes it easy to see who you match in common with someone else in their matching tool, by utilizing the ICW crossed X icon.

In the above example, I am seeing who I match in common with my mother. Sure enough, our three known cousins are the closest matches, shown below.

You can then push up to 5 individuals through to the chromosome browser to see where they match the participant.

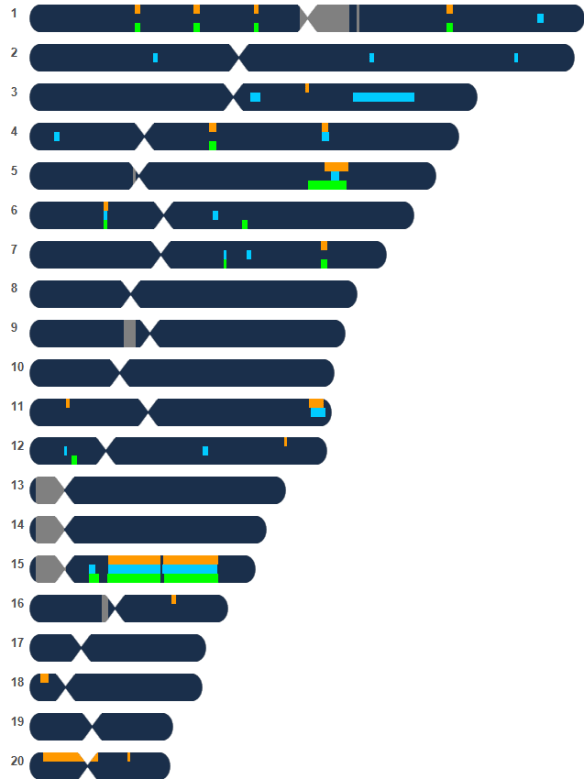

The following chromosome browser is an example of a 4 person match showing up on the Family Tree DNA chromosome browser.

This example shows known cousins matching. But this is exactly the same scenario you’re looking for when you are matching previously unknown cousins – the exact same technique.

In this example, I am the participant, so these matches are matches to me and my chromosome is the background chromosome displayed. I have switched from my mother’s side to known cousins on my father’s side.

The chromosome browser shows that these three cousins all match the person whose chromosomes are being shown (me, in this case), but it doesn’t tell you if they also match each other. With known cousins, it’s very unlikely (in my case) that someone would match me from my mother’s side, and someone from my father’s side, but when you’re working with unknown cousins, it’s certainly possible. If your parents are from the same core population, like Germans or an endogamous population, you may well have people who match you on both sides of your family. Simply put, you can’t assume they don’t.

It’s also possible that the match is a genuine genealogical match, but you don’t happen to match on the exact same segments, so the ancestor can’t yet be confirmed until more cousins sharing that same ancestral line are found who do match, and it’s possible that some segments could be IBS, identical by state, meaning matches by chance, especially small segments, below the match threshold.

2. Matrix – do they match each other?

Family Tree DNA also provides a tool called the Matrix where you can see if all of the people who match on the same segment, also match each other at some place on their DNA.

The Matrix tool measures the same level of DNA as the default chromosome browser, so in the situation I’m using for an example, there is no issue. However, if you drop the threshold of the match level, you may well, and in this case, you will, find matches well below the match threshold. They are shown as matches because they have at least one segment above the match threshold. If you don’t have at least one segment above the threshold, you’ll never see these smaller matches. Just to show you what I mean, this is the same four people, above, with the threshold lowered to 1cM. All those little confetti pieces of color are smaller matches.

At Family Tree DNA, the match threshold is about 7cM. Each of the vendors has a different threshold and a different way of calculating that threshold.

The only reason I mention this is because if you DON’T match with someone on the matrix, but you also show matches at smaller segments, understand that matrix is not reporting on those, so matrix matches are not negative proof, only positive indications – when you do match, both on the chromosome browser and utilizing the matrix tool.

What you do know at this point is that these individuals all match you on the same segments, and that they match each other someplace on their chromosomes, but what you don’t know is if they match each other on the same locations where they match you.

If you are lucky and your matches are cousins or experienced genetic genealogists and are willing to take a look at their accounts, they can tell you if they match the other people on the same segments where they match you – but that’s the only way to know unless they are willing to download their raw data file to GedMatch. At GedMatch, you can adjust the match thresholds to any level you wish and you can compare one-to-one kits to see where any two kits who have provided you with their kit number match each other.

3. Downloading data – mapping your chromosome.

The “download to Excel” function at Family Tree DNA, located just above the chromosome browser graphic, on the left, provides you with the matching data of the individuals shown on the chromosome browser with their actual segment data shown. (The download button on the right downloads all of your matches, not just the ones shown in the browser comparison.)

The spreadsheet below shows the downloaded data for these four individuals. You can see on chromosome 15 (yellow) there are three distinct segments that match (pink, yellow and blue,) which is exactly what is reflected on the graphic browser as well.

On the spreadsheet below, I’ve highlighted, in red, the segments which appeared on the original chromosome browser – so these are only the matches at or over the match threshold.

As you can see, there are 13 in total.

Smaller Segments

Up to this point, the process I’ve shared is widely accepted as the gold standard.

In the genetic genealogy community, there are very divergent opinions on how to treat segments below the match threshold, or below even 10cM. Some people “throw them away,” in essence, disregard them entirely. Before we look at a real life example, let’s talk about the challenges with small segments.

When smaller segments match, along with larger segments, I don’t delete them, throw them away, or disregard them. I believe that they are tools and each one carries a message for us. Those messages can be one of four things.

- This is a valid IBD, meaning identical by descent, match where the segment has been passed from one specific ancestor to all of the people who match and can be utilized as such.

- This is an IBS match, meaning identical by state, and is called that because we can’t yet identify the common ancestor, but there is one. So this is actually IBD but we can’t yet identify it as such. With more matches, we may well be able to identify it as IBD, but if we throw it away, we never get that chance. As larger data bases and more sophisticated software become available, these matches will fall into place.

- This is an IBS match that is a false match, meaning the DNA segments that we receive from our father and mother just happen to align in a way that matches another person. Generally these are relatively easy to determine because the people you match won’t match each other. You also won’t tend to match other people with the same ancestral line, so they will tend to look like lone outliers on your match spreadsheets, but not always.

- This is an IBS match that is population based. These are much more difficult to determine, because this is a segment that is found widely in a population. The key to determining these pileup areas, as discussed in the Ancestry article about their new phasing technique, if that you will find this same segment matching different proven lineages. This is the reason that Ancestry has implemented phasing – to identify and remove these match regions from your matches. Ancestry provided a graphic of my pileup areas, although they did not identify for me where on my chromosomes these pileup regions occurred. I do have some idea however, because I’ve found a couple of areas where I have matches from my mother’s side of the family from different ancestors – so these areas must be IBS on a population level. That does not, however, make them completely irrelevant.

The challenge, and problem, is where to make the cutoff when you’re eliminating match areas based on phased data. For example, I lost all of my Acadian matches at Ancestry. Of course, you would expect an endogamous population to share lots of the same DNA – and there are a huge number of Acadian descendants today – they are in fact a “population,” but those matches are (were) still useful to me.

I utilize Acadian matches from Family Tree DNA and 23andMe to label that part of my chromosome “Acadian” even if I can’t track it to a specific Acadian ancestor, yet. I do know from which of my mother’s ancestors it originated, her great-grandfather, who is her Acadian ancestor. Knowing that much is useful as well.

The same challenge exists for other endogamous groups – people with Jewish, Mennonite/Brethren/Amish, Native American and African American heritage searching for their mixed race roots arising from slavery. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that this problem exists for anyone looking for ancestors beyond the 5th or 6th generation, because segments inherited from those ancestors, if there are any, will probably be small and fall below the generally accepted match thresholds. The only way you will be able to find them, today, is the unlikely event that there is one larger segments, and it leads you on a search, like the case with Sarah Hickerson.

I want to be very clear – if you’re looking for only “sure thing” segments – then the larger the matching segment, the better the odds that it’s a sure thing, a positive, indisputable, noncontroversial match. However, if you’re looking for ancestors in the distant past, in the 5th or 6th generation or further, you’re not likely to find sure thing matches and you’ll have to work with smaller segments. It’s certainly preferable and easier to work with large matches, but it’s not always possible.

In the Ralph and Coop paper, The Geography of Recent Genetic Ancestry Across Europe, they indicated that people who matched on segments of 10cM or larger were more likely to have a common ancestor with in the past 500 years. Blocks of 4cM or larger were estimated to be from populations from 500-1500 years ago. However, we also know that there are indeed sticky segments that get passed intact from generation to generation, and also that some segments don’t get divided in a generation, they simply disappear and aren’t passed on at all. I wrote about this in my article titled, Generational Inheritance.

Another paper by Durand et al, Reducing pervasive false positive identical-by-descent segments detected by large-scale pedigree analysis, showed that 67% of the 2-4cM segments were false positives. Conversely, that also means that 33% of the 2-4cM segments were legitimate IBD segments.

Part of the disagreement within the genetic genealogy community is based on a difference in goals. People who are looking for the parents of adoptees are looking first and primarily as “sure thing” matches and the bigger the match segment, of course, the better because that means the people are related more closely in time. For them, smaller segments really are useless. However, for people who know their recent genealogy and are looking for those brick wall ancestors, several generations back in time, their only hope is utilizing those smaller segments. This not black and white but shades of grey. One size does not fit all. Nor is what we know today the end of the line. We learn every single day and many of our learning experiences are by working through our own unique genealogical situations – and sharing our discoveries.

On this next spreadsheet, you can see the smaller segments surrounding the larger segments – in other words, in the same match cluster – highlighted in green. These are the segments that would be discarded as invalid if you were drawing the line at the match threshold. Some people draw it even higher, at 10 cM. I’m not being critical of their methodology or saying they are wrong. It may well work best for them, but discarding small segments is not the only approach and other approaches do work, depending on the goals of the researcher. I want my 33% IBD segments, thank you very much.

All of the segments highlighted in purple match between at least three cousins. By checking the other cousins accounts, I can validate that they do all match each other as well, even though I can’t tell this through the Family Tree DNA matrix below the matching threshold. So, I’ve proven these are valid. We all received them from our common ancestor.

What about the white rows? Are those valid matches, from a common ancestor? We don’t have enough information to make that determination today.

Downloading my data, and confirming segments to this common ancestor allows me to map my own chromosomes. Now, I know that if someone matches me and any of these three cousins on chromosome 15, for example, between 33,335,760 and 58,455,135 – they are, whether they know it or not, descended from our common ancestral line.

In my opinion, I would think it a shame to discount or throw away all of these matches below 7cM, because you would be discounting 39 of your 52 total matches, or 75% of them. I would be more conservative in assigning my segments with only one cousin match to any ancestor, but I would certainly note the match and hope that if I added other cousins, that segment would be eventually proven as IBD.

I used positively known cousins in this example because there is no disputing the validity of these matches. They were known as cousins long before DNA testing.

Breaking Down Brick Walls

This is the same technique utilized to break down brick walls – and the more cousins you have tested, so that you can identify the maximum number of chromosome pieces of a particular ancestor – the better.

I used this same technique to identify Sarah Hickerson in my Thanksgiving Day article, utilizing these same cousins, plus several more.

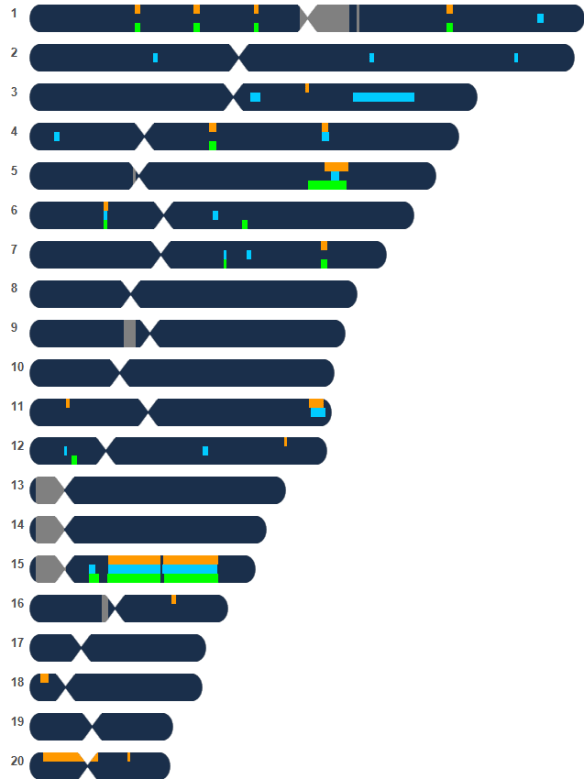

Hey, just for fun, want to see what chromosome 15 looks like in this much larger sample???

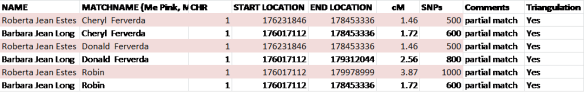

In this case, we were trying to break down a brick wall. We needed to determine if Sarah Hickerson was the mother of Elijah Vannoy. All of the individuals in the left “Name” column are proven Vannoy cousins from Elijah, or in one case, William, from another child of Sarah Hickerson. The individuals in the right “Match” column are everyone in the cousin match group plus the people in green who are Hickerson/Higginson descendants. William, in green, is proven to descend from Sarah Hickerson and her husband, Daniel Vannoy.

The first part of chromosome 15 doesn’t overlap with the rest. Buster, David and I share another ancestral line as well, so the match in the non-red section of chromosome 15 may well be from that ancestral line. It becomes an obvious possibility, because none of the people who share the Vannoy/Hickerson/Higginson DNA are in that small match group.

All of the red colored cells do overlap with at least one other individual in that group and together they form a cluster. The yellow highlighted cells are the ones over the match threshold. The 6 Hickerson/Higginson descendants are scattered throughout this match group.

And yes, for those who are going to ask, there are many more Vannoy/Hickerson triangulated groups. This is just one of over 60 matching groups in total, some with matches well above the match threshold. But back to the chromosome browser wars!

23andMe

This example from 23andMe shows why it’s so very important to verify that your matches also match each other.

Blue and purple match segments are to two of the same cousins that I used in the comparison at Family Tree DNA, who are from my father’s side. Green is my first cousin from my mother’s side. Note that on chromosome 11, they both match me on a common segment. I know by working with them that they don’t match each other on that segment, so while they are both related to me, on chromosome 11, it’s not through the same ancestor. One is from my father’s side and one is from my mother’s side. If I hadn’t already known that, determining if they matched each other would be the acid test and would separate them into 2 groups.

23andMe provides you with a tool to see who your matches match that you match too. That’s a tongue twister.

In essence, you can select any individual, meaning you or anyone that you match, on the left hand side of this tool, and compare them to any 5 other people that you match. In my case above, I compared myself to my cousins, but if I want to know if my cousin on my mother’s side matches my two cousins on my father’s side, I simply select her name on the left and theirs on the right by using the drop down arrows.

I would show you the results, but it’s in essence a blank chromosome browser screen, because she doesn’t match either of them, anyplace, which tells me, if I didn’t already know, that these two matches are from different sides of my family.

However, in other situations, where I match my cousin Daryl, for example, as well as several other people on the same segment, I want to know how many of these people Daryl matches as well. I can enter Daryl’s name, with my name and their names in the group of 5, and compare. 23andMe facilitates the viewing or download of the results in a matrix as well, along with the segment data. You can also download your entire list of matches by requesting aggregated data through the link at the bottom of the screen above or the bottom of the chromosome display.

I find it cumbersome to enter each matches name in the search tool and then enter all of the other matches names as well. By utilizing the tools at www.dnagedcom.com, you can determine who your matches match as well, in common with you, in one spreadsheet. Here’s an example. Daryl in the chart below is my match, and this tool shows you who else she matches that I match as well, and the matching segments. This allows me to correlate my match with Gwen for example, to Daryl’s match to Gwen to see if they are on the same segments.

As you can see, Daryl and I both match Gwen on a common segment. On my own chromosome mapping spreadsheet, I match several other people as well at that location, at other vendors, but so far, we haven’t been able to find any common genealogy.

Ancestry.com

At Ancestry.com, I have exactly the opposite problem. I have lots of people I DNA match, and some with common genealogy, but no tools to prove the DNA match is to the common ancestor.

Hence, this is the crux of the chromosome browser wars. I’ve just showed you how and why we use chromosome browsers and tools to show if our matches match each other in addition to us and on which segments. I’ve also illustrated why. Neither 23andMe nor Family Tree DNA provides perfect tools, which is why we utilize both GedMatch and DNAGedcom, but they do provide tools. Ancestry provides no tools of this type.

At Ancestry, you have two kinds of genetic matches – ones without tree matches and ones with tree matches. Pedigree matching is a service that Ancestry provides that the other vendors don’t. Unfortunately, it also leads people to believe that because they match these people genetically and share a tree, that the tree shown is THE genetic match and it’s to the ancestor shown in the tree. In fact, if the tree is wrong, either your tree or their tree, and you match them genetically, you will show up as a pedigree match as well. Even if both pedigrees are right, that still doesn’t mean that your genetic match is through that ancestor.

How many bad trees are at Ancestry percentagewise? I don’t know, but it’s a constant complaint and there is absolutely nothing Ancestry can do about it. All they can do is utilize what they have, which is what their customers provide. And I’m glad they do. It does make the process of working through your matches much easier. It’s a starting point. DNA matches with trees that also match your pedigree are shown with Ancestry’s infamous shakey leaf.

In fact, in my Sarah Hickerson article, it was a shakey leaf match that initially clued me that there was something afoot – maybe. I had to shift to another platform (Family Tree DNA) to prove the match however, where I had tools and lots of known cousins.

At Ancestry, I now have about 3000 matches in total, and of those, I have 33 shakey leaves – or people with whom I also share an ancestor in our pedigree charts. A few of those are the same old known cousins, just as genealogy crazy as me, and they’ve tested at all 3 companies.

The fly in the ointment, right off the bat, is that I noticed in several of these matches that I ALSO share another ancestral line.

Now, the great news is that Ancestry shows you your surnames in common, and you can click on the surname and see the common individuals in both trees.

The bad news is that you have to notice and click to see that information, found in the lower left hand corner of this screen.

In this case, Cook is an entirely different line, not connected to the McKee line shown.

However, in this next case, we have the same individual entered in our software, but differently. It wasn’t close enough to connect as an ancestor, but close enough to note. It turns out that Sarah Cook is the mother of Fairwick Claxton, but her middle name was not Helloms, nor was her maiden name, although that is a long-standing misconception that was proven incorrect with her husband’s War of 1812 documents many years ago. Unfortunately, this misinformation is very widespread in trees on the internet.

Out of curiosity, and now I’m sorry I did this because it’s very disheartening – I looked to see what James Lee Claxton/Clarkson’s wife’s name was shown to be on the first page of Ancestry’s advanced search matches.

Despite extensive genealogical and DNA research, we don’t know who James Lee Claxton/Clarkson’s parents are, although we’ve disproven several possibilities, including the most popular candidate pre-DNA testing. However, James’ wife was positively Sarah Cook, as given by her, along with her father’s name, and by witnesses to their marriage provided when she applied for a War of 1812 pension and bounty land. I have the papers from the National Archives.

James Lee Claxton’s wife, Sara Cook is identified as follows in the first 50 Ancestry search entries.

Sarah Cook – 4

Incorrect entries:

- Sarah Cook but with James’ parents listed – 3

- Sarah Helloms Cook – 2, one with James’ parents

- Sarah Hillhorns – 15

- Sarah Cook Hitson – 13, some with various parents for James

- No wife, but various parents listed for James – 12

- No wife, no parents – 1

I’d much rather see no wife and no parents than incorrect information.

Judy Russell has expressed her concern about the effects of incorrect trees and DNA as well and we shared this concern with Ancestry during our meeting.

Ancestry themselves in their paper titled “Identifying groups of descendants using pedigrees and genetically inferred relationships in a large database” says, “”As with all analyses relating to DNA Circles™, tree quality is also an important caveat and limitation.” So Ancestry is aware, but they are trying to leverage and utilize one of their biggest assets, their trees.

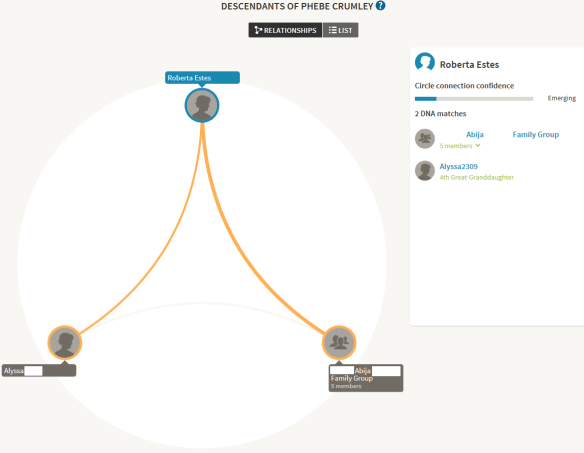

This brings us to DNA Circles. I reviewed Ancestry’s new product release extensively in my Ancestry’s Better Mousetrap article. To recap briefly, Ancestry gathers your DNA matches together, and then looks for common ancestors in trees that are public using an intelligent ranking algorithm that takes into account:

- The confidence that the match is due to recent genealogical history (versus a match due to older genealogical history or a false match entirely).

- The confidence that the identified common recent ancestor represents the same person in both online pedigrees.

- The confidence that the individuals have a match due to the shared ancestor in question as opposed to from another ancestor or from more distant genealogical history.

The key here is that Ancestry is looking for what they term “recent genealogical history.” In their paper they define this as 10 generations, but the beta version of DNA Circles only looks back 7 generations today. This was also reflected in their phasing paper, “Discovering IBD matches across a large, growing database.”

However, the unfortunate effect has been in many cases to eliminate matches, especially from endogamous groups. By way of example, I lost my Acadian matches in the Ancestry new product release. They would have been more than 7 generations back, and because they were endogamous, they may have “looked like” IBS segments, if IBS is defined at Ancestry as more than 7 or 10 generations back. Hopefully Ancestry will tweek this algorithm in future releases.

Ancestry, according to their paper, “Identifying groups of descendants using pedigrees and genetically inferred relationships in a large database,” then clusters these remaining matching individuals together in Circles based on their pedigree charts. You will match some of these people genetically, and some of them will not match you but will match each other. Again, according to the paper, “these confidence levels are calculated by the direct-line pedigree size, the number of shared ancestral couples and the generational depth of the shared MRCA couple.”

Ancestry notes that, “using the concordance of two independent pieces of information, meaning pedigree relationships and patterns of match sharing among a set of individuals, DNA Circles can serve as supporting evidence for documented pedigree lines.” Notice, Ancestry did NOT SAY proof. Nothing that Ancestry provides in their DNA product constitutes proof.

Ancestry continues by saying that Circles “opens the possibility for people to identify distant relatives with whom they do not share DNA directly but with whom they still have genetic evidence supporting the relationship.”

In other words, Ancestry is being very clear in this paper, which is provided on the DNA Circles page for anyone with Circles, that they are giving you a tool, not “the answer,” but one more piece of information that you can consider as evidence.

You can see in my Joel Vannoy circle that I match both of these people both genetically and on their tree.

We, in the genetic genealogy community, need proof. It certainly could be available, technically – because it is with other vendors and third party sites.

We need to be able to prove that our matches also match each other, and utilizing Ancestry’s tools, we can’t. We also can’t do this at Ancestry by utilizing third party tools, so we’re in essence, stuck.

We can either choose to believe, without substantiation, that we indeed share a common ancestor because we share DNA segments with them plus a pedigree chart from that common ancestor, or we can initiate a conversation with our match that leads to either or both of the following questions:

- Have you or would you upload your raw data to GedMatch?

- Have you or would you upload your raw data file to Family Tree DNA?

Let the begging begin!!!

The Problem

In a nutshell, the problem is that even if your Ancestry matches do reply and do upload their file to either Family Tree DNA or GedMatch or both, you are losing most of the potential information available, or that would be available, if Ancestry provided a chromosome browser and matrix type tool.

In other words, you’d have to convince all of your matches and then they would have to convince all of the matches in the circle that they match and you don’t to upload their files.

Given that, of the 44 private tree shakey leaf matches that I sent messages to about 2 weeks ago, asking only for them to tell me the identity of our common pedigree ancestor, so far 2 only of them have replied, the odds of getting an entire group of people to upload files is infinitesimal. You’d stand a better chance of winning the lottery.

One of the things Ancestry excels at is marketing.

If you’ve seen any of their ads, and they are everyplace, they focus on the “feel good” and they are certainly maximizing the warm fuzzy feelings at the holidays and missing those generations that have gone before us.

This is by no means a criticism, but it is why so many people do take the Ancestry DNA test. It’s advertised as easy and you’ll learn more about your family. And you do, no question – you learn about your ethnicity and you get a list of DNA matches, pedigree matches when possible and DNA Circles.

The list of what you don’t get is every bit as important, a chromosome browser and tools to see whether your matches also match each other. However, most of their customers will never know that.

Judging by the high percentage of inaccurate trees I found at Ancestry in my little experiment relative to the known and documented wife’s name of James Lee Claxton, which was 96%, based on just the first page of 50 search matches, it would appear that about 96% of Ancestry’s clientele are willing to believe something that someone else tells them without verification. I doubt that it matters whether that information is a tree or a DNA test where they are shown matches with common pedigree charts and circles. I don’t mean this to be critical of those people. We all began as novices and we need new people to become interested in both genealogy and DNA testing.

I suspect that most of Ancestry’s clients, especially new ones, simply don’t have a clue that there is a problem, let alone the magnitude and scope. How would they? They are just happy to find information about their ancestor. And as someone said to me once – “but there are so many of those trees (with a wrong wife’s name), how can they all be wrong?” Plus, the ads, at least some of them, certainly suggest that the DNA test grows your family tree for you.

The good news in all of this is that Ancestry’s widespread advertising has made DNA testing just part of the normal things that genealogists do. Their marketing expertise along with recent television programs have served to bring DNA testing into the limelight. The bad news is that if people test at Ancestry instead of at a vendor who provides tools, we, and they, lose the opportunity to utilize those results to their fullest potential. We, and they, lose any hope of proving an ancestor utilizing DNA. And let’s face it, DNA testing and genealogy is about collaboration. Having a DNA test that you don’t compare against others is pointless for genealogy purposes.

When a small group of bloggers and educators visited Ancestry in October, 2014, for what came to be called DNA Day, we discussed the chromosome browser and Ancestry’s plans for their new DNA Circles product, although it had not yet been named at that time. I wrote about that meeting, including the fact that we discussed the need for a chromosome browser ad nauseum. Needless to say, there was no agreement between the genetic genealogy community and the Ancestry folks.

When we discussed the situation with Ancestry they talked about privacy and those types of issues, which you can read about in detail in that article, but I suspect, strongly, that the real reason they aren’t keen on developing a chromosome browser lies in different areas.

- Ancestry truly believes that people cannot understand and utilize a chromosome browser and the information it provides. They believe that people who do have access to chromosome browsers are interpreting the results incorrectly today.

- They do not want to implement a complex feature for a small percentage of their users…the number bantered around informally was 5%…and I don’t know if that was an off-the-cuff number or based on market research. However, if you compare that number with the number of accurate versus inaccurate pedigree charts in my “James Claxton’s wife’s name” experiment, it’s very close…so I would say that the 5% number is probably close to accurate.

- They do not want to increase their support burden trying to explain the results of a chromosome browser to the other 95%. Keep in mind the number of users you’re discussing. They said in their paper they had 500,000 DNA participants. I think it’s well over 700,000 today, and they clearly expect to hit 1 million in 2015. So if you utilize a range – 5% of their users are 25,000-50,000 and 95% of their users are 475,000-950,000.

- Their clients have already paid their money for the test, as it is, and there is no financial incentive for Ancestry to invest in an add-on tool from which they generate no incremental revenue and do generate increased development and support costs. The only benefit to them is that we shut up!

So, the bottom line is that most of Ancestry’s clients don’t know or care about a chromosome browser. There are, however, a very noisy group of us who do.

Many of Ancestry’s clients who purchase the DNA test do so as an impulse purchase with very little, if any, understanding of what they are purchasing, what it can or will do for them, at Ancestry or anyplace else, for that matter.

Any serious genealogist who researched the autosomal testing products would not make Ancestry their only purchase, especially if they could only purchase one test. Many, if not most, serious genealogists have tested at all three companies in order to fish in different ponds and maximize their reach. I suspect that most of Ancestry’s customers are looking for simple and immediate answers, not tools and additional work.

The flip side of that, however, if that we are very aware of what we, the genetic genealogy industry needs, and why, and how frustratingly lacking Ancestry’s product is.

Company Focus

It’s easy for us as extremely passionate and focused consumers to forget that all three companies are for-profit corporations. Let’s take a brief look at their corporate focus, history and goals, because that tells a very big portion of the story. Every company is responsible first and foremost to their shareholders and owners to be profitable, as profitable as possible which means striking the perfect balance of investment and expenditure with frugality. In corporate America, everything has to be justified by ROI, or return on investment.

Family Tree DNA

Family Tree DNA was the first one of the companies to offer DNA testing and was formed in 1999 by Bennett Greenspan and Max Blankfeld, both still principles who run Family Tree DNA, now part of Gene by Gene, on a daily basis. Family Tree DNA’s focus is only on genetic genealogy and they have a wide variety of products that produce a spectrum of information including various Y DNA tests, mitochondrial, autosomal, and genetic traits. They are now the only commercial company to offer the Y STR and mitochondrial DNA tests, both very important tools for genetic genealogists, with a great deal of information to offer about our ancestors.

In April 2005, National Geographic’s Genographic project was announced in partnership with Family Tree DNA and IBM. The Genographic project, was scheduled to last for 5 years, but is now in its 9th year. Family Tree DNA and National Geographic announced Geno 2.0 in July of 2012 with a newly designed chip that would test more than 12,000 locations on the Y chromosome, in addition to providing other information to participants.

The Genographic project provided a huge boost to genetic genealogy because it provided assurance of legitimacy and brought DNA testing into the living room of every family who subscribed to National Geographic magazine. Family Tree DNA’s partnership with National Geographic led to the tipping point where consumer DNA testing became mainstream.

In 2011 the founders expanded the company to include clinical genetics and a research arm by forming Gene by Gene. This allowed them, among other things, to bring their testing in house by expanding their laboratory facilities. They have continued to increase their product offerings to include sophisticated high end tests like the Big Y, introduced in 2013.

23andMe

23andMe is also privately held and began offering testing for medical and health information in November 2007, initially offering “estimates of predisposition for more than 90 traits ranging from baldness to blindness.” Their corporate focus has always been in the medical field, with aggregated customer data being studied by 23andMe and other researchers for various purposes.

In 2009, 23andMe began to offer the autosomal test for genealogists, the first company to provide this service. Even though, by today’s standards, it was very expensive, genetic genealogists flocked to take this test.

In 2013, after several years of back and forth with 23andMe ultimately failing to reply to the FDA, the FDA forced 23andMe to stop providing the medical results. Clients purchasing the 23andMe autosomal product since November of 2013 receive only ethnicity results and the genealogical matching services.

In 2014, 23andMe has been plagued by public relations issues and has not upgraded significantly nor provided additional tools for the genetic genealogy community, although they recently formed a liaison with My Heritage.

23andMe is clearly focused on genetics, but not primarily genetic genealogy, and their corporate focus during this last year in particular has been, I suspect, on how to survive, given the FDA action. If they steer clear of that landmine, I expect that we may see great things in the realm of personalized medicine from them in the future.

Genetic genealogy remains a way for them to attract people to increase their data base size for research purposes. Right now, until they can again begin providing health information, genetic genealogists are the only people purchasing the test, although 23andMe may have other revenue sources from the research end of the business

Ancestry.com

Ancestry.com is a privately held company. They were founded in the 1990s and have been through several ownership and organizational iterations, which you can read about in the wiki article about Ancestry.

During the last several years, Ancestry has purchased several other genealogy companies and is now the largest for-profit genealogy company in the world. That’s either wonderful or terrible, depending on your experiences and perspective.

Ancestry has had an on-again-off-again relationship with DNA testing since 2002, with more than one foray into DNA testing and subsequent withdrawal from DNA testing. If you are interested in the specifics, you can read about them in this article.

Ancestry’s goal, as it is with all companies, is profitability. However, they have given themselves a very large black eye in the genetic genealogy community by doing things that we consider to be civically irresponsible, like destroying the Y and mitochondrial DNA data bases. This still makes no sense, because while Ancestry spends money on one hand to acquire data bases and digitize existing records, on the other hand, they wiped out a data base containing tens of thousands of irreplaceable DNA records, which are genealogy records of a different type. This was discussed at DNA Day and the genetic genealogy community retains hope that Ancestry is reconsidering their decision.

Ancestry has been plagued by a history of missteps and mediocrity in their DNA products, beginning with their Y and mitochondrial DNA products and continuing with their autosomal product. Their first autosomal release included ethnicity results that gave many people very high percentages of Scandinavian heritage. Ancestry never acknowledged a problem and defended their product to the end…until the day when they announced an update titled….a whole new you. They are marketing geniuses. While many people found their updated product much more realistic, not everyone was happy. Judy Russell wrote a great summary of the situation.

It’s difficult, once a company has lost their credibility, for them to regain it.

I think Ancestry does a bang up job of what their primary corporate goal is….genealogy records and subscriptions for people to access those records. I’m a daily user. Today, with their acquisitions, it would be very difficult to be a serious genealogist without an Ancestry subscription….which is of course what their corporate goal has been.

Ancestry does an outstanding job of making everything look and appear easy. Their customer interface is intuitive and straightforward, for the most part. In fact, maybe they have made both genealogy and genetic genealogy look a little too easy. I say this tongue in cheek, full well knowing that the ease of use is how they attract so many people, and those are the same people who ultimately purchase the DNA tests – but the expectation of swabbing and the answer appearing is becoming a problem. I’m glad that Ancestry has brought DNA testing to so many people but this success makes tools like the chromosome browser/matrix that much more important – because there is so much genealogy information there just waiting to be revealed. I also feel that their level of success and visibility also visits upon them the responsibility for transparency and accuracy in setting expectations properly – from the beginning – with the ads. DNA testing does not “grow your tree” while you’re away.

I’m guessing Ancestry entered the DNA market again because they saw a way to sell an additional product, autosomal DNA testing, that would tie people’s trees together and provide customers with an additional tool, at an additional price, and give them yet another reason to remain subscribed every year. Nothing wrong with that either. For the owners, a very reasonable tactic to harness a captive data base whose ear you already have.

But Ancestry’s focus or priority is not now, and never has been, quality, nor genetic genealogy. Autosomal DNA testing is a tool for their clients, a revenue generation source for them, and that’s it. Again, not a criticism. Just the way it is.

In Summary

As I look at the corporate focus of the three players in this space, I see three companies who are indeed following their corporate focus and vision. That’s not a bad thing, unless the genetic genealogy community focus finds itself in conflict with the results of their corporate focus.

It’s no wonder that Family Tree DNA sponsors events like the International DNA Conference and works hand in hand with genealogists and project administrators. Their focus is and always has been genetic genealogy.

People do become very frustrated with Family Tree DNA from time to time, but just try to voice those frustrations to upper management at either 23andMe or Ancestry and see how far you get. My last helpdesk query to 23andMe submitted on October 24th has yet to receive any reply. At Family Tree DNA, I e-mailed the project administrator liaison today, the Saturday after Thanksgiving, hoping for a response on Monday – but I received one just a couple hours later – on a holiday weekend.

In terms of the chromosome browser war – and that war is between the genetic genealogy community and Ancestry.com, I completely understand both positions.

The genetic genealogy community has been persistent, noisy, and united. Petitions have been created and signed and sent to Ancestry upper management. To my knowledge, confirmation of any communications surrounding this topic with the exception of Ancestry reaching out to the blogging and education community, has never been received.

This lack of acknowledgement and/or action on the issues at hand frustrates the community terribly and causes reams of rather pointed and very direct replies to Anna Swayne and other Ancestry employees who are charged with interfacing with the public. I actually feel sorry for Anna. She is a very nice person. If I were in her position, I’d certainly be looking for another job and letting someone else take the brunt of the dissatisfaction. You can read her articles here.

I also understand why Ancestry is doing what they are doing – meaning their decision to not create a chromosome browser/match matrix tool. It makes sense if you sit in their seat and now have to look at dealing with almost a million people who will wonder why they have to use a chromosome browser and or other tools when they expected their tree to grow while they were away.

I don’t like Ancestry’s position, even though I understand it, and I hope that we, as a community, can help justify the investment to Ancestry in some manner, because I fully believe that’s the only way we’ll ever get a chromosome browser/match matrix type tool. There has to be a financial benefit to Ancestry to invest the dollars and time into that development, as opposed to something else. It’s not like Ancestry has additional DNA products to sell to these people. The consumers have already spent their money on the only DNA product Ancestry offers, so there is no incentive there.

As long as Ancestry’s typical customer doesn’t know or care, I doubt that development of a chromosome browser will happen unless we, as a community, can, respectfully, be loud enough, long enough, like an irritating burr in their underwear that just won’t go away.

The Future

What we “know” and can do today with our genomes far surpasses what we could do or even dreamed we could do 10 years ago or even 5 or 2 years ago. We learn everyday.

Yes, there are a few warts and issues to iron out. I always hesitate to use words like “can’t,” “never” and “always” or to use other very strongly opinionated or inflexible words, because those words may well need to be eaten shortly.

There is so much more yet to be done, discovered and learned. We need to keep open minds and be willing to “unlearn” what we think we knew when new and better information comes along. That’s how scientific discovery works. We are on the frontier, the leading edge and yes, sometimes the bleeding edge. But what a wonderful place to be, to be able to contribute to discovery on a new frontier, our own genes and the keys to our ancestors held in our DNA.

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

Like this:

Like Loading...

Which walls do you need to fall and how can you use this technique?

Which walls do you need to fall and how can you use this technique?