Today, what I’m sharing with you are my research notes. If you follow my blogs, you’ll know that I have a fundamental, lifelong interest in Native American people and am mixed blood myself. I feel that DNA is just one of the pieces of history that can be recovered and has a story to tell, along with early records, cultural artifacts and oral history.

In order to work with Native American DNA, and the various DNA projects that I co-administer, it’s necessary to keep a number of lists and spreadsheets. This particular list was originally the first or earliest reference or references to a Native American mitochondrial (maternal line) haplogroup where it is identified as Native in academic papers. I have since added other resources as I’ve come across them.

For those wondering why I’ve listed Mexican, this article speaks to the very high percentage of Native American mitochondrial DNA in the Mexican population.

Please note that while some of these haplogroups are found exclusively among Native American people, others are not and are also found in Europe and/or Asia. In some cases, branches are exclusively Native. In other cases, we are still sorting through the differences. For haplogroups though to be only Native, I have put any other submission information, which is often from Siberia.

I have labeled the major founding haplogroups, as such. This graphic from the paper, “Beringian Standstill and the Spread of Native American Founders” by Tamm et al, provided the first cumulative view of the mitochondrial Native founder population.

Haplogroups A, B, C, D and X are known as Native American haplogroups, although not all subgroups in each main haplogroup are Native, so one has to be more specific.

Please note that I am adding information from haplogroup projects at Family Tree DNA. This information is self-reported and should only be utilized with confidence after confirming the accuracy of the information.

Please note that in earlier papers and projects, not all results may have been tested to the full sequence level, so results in base haplogroups, like A and B, for example, may well fall into subclades with additional testing.

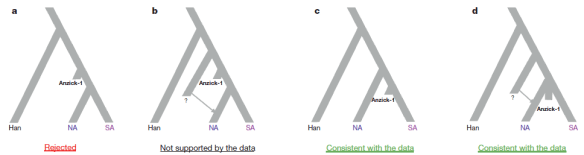

The protocol and logic for adding the Anzick results for consideration, along with other evidence is discussed in this article. In short, for the 12,500 year old Anzick specimen to match any currently living people at relatively high thresholds, meaning 5cM or over, the living individual would likely have to be heavily Native. Most matches are from Mexico, Central America and South America. Many mitochondrial DNA haplogroups are subgroups of known Native groups, but never before documented as Native. Therefore, the protocol I followed for inclusion was any subgroup of haplogroups A, B, C, D, M or X. Some individuals are unhappy that some haplogroups were among the Anzick results and that I have not removed them at their request, in particular, M23. To arbitrarily remove a haplogroup listing would be a breach of the protocol I followed. Research does not always provide what is expected. I have includes links to notes where appropriate.

Phylotree Versions

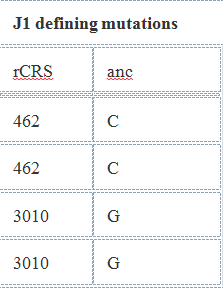

The Phylotree is the document that defines the mutations that equate to haplogroup names.

Please note that most papers don’t indicate which version of the Phylotree they used when sequencing the DNA. Haplogroup names sometimes change with new versions of the Phylotree. Phylotree builds occurred as follows:

Family Tree DNA updated from build 14 to 17 in March 2017.

As of April 2017, 23andMe is still utilizing Build 12 from 2011.

Roberta’s Native Mitochondrial DNA Notes

Haplogroup A

A

Many samples classified as haplogroup A, with no subgroup, were not tested beyond the HVR1 or HVR1+HVR2 regions. Most, but not all, people will receive more granular haplogroups if the full mitochondrial sequence test is taken.

- Tribes or peoples include Cherokee, Choctaw, Chippewa, Cree, Huron, Mi’kmaq, and PeeDee found in 2021 in the Haplogroup A project , Acadian AmerIndian Ancestry project and American Indian projects at Family Tree DNA.

- Ancestral locations in 2021 include Alaska, Alberta, Argentina, Arizona, Bahamas, Belize, Brazil, British Colombia, California, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Indiana, Kuna-Panama, Louisiana, Manitoba, Mexico, New Mexico, Nicaragua, North Carolina, Nova Scotia, Ohio, Panama, Puerto Rico, Saskatchewan, South Carolina, Texas, Wisconsin, Venezuela.

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes 2014

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (32 As with no subgroup)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

Ancient A

- Ancient samples from Antaura (1) and Puca (5) 1100-1500 BC. Baca, 2014

- Ancient sample named Kwäday Dän Ts’ìchi, Long-Ago Person Found from the glacier at Tatshenshini-Alsek Park, Canada, dates from about 1420 CE, Monsalve 2002

- Ancient samples (2) from Tompullo and Andaray, Peru dating from about 1450 CE, Baca, 2012

A-T152C!

A1

- Mexican – 2007 Peñaloza-Espinosa

- Rumsen, Esselen, Salinan from Monterey, California – Breschini and Haversat 2008

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- In Build 17, previous haplogroup A4a became A1

- Please note that in 2021, haplogroups A1 and A1a appear not to be Native, but there remains some question. In the next version of the haplotree as a result of the Million Mito Project, we can hopefully resolve this question.

A1a

- In Build 17, previous haplogroup A4a1 became A1a

- Please note that in 2021, haplogroups A1 and A1a appear not to be Native, but there remains some question. In the next version of the haplotree as a result of the Million Mito Project, we can hopefully resolve this question.

A2

- Native, Beringian Founder Haplogroup – 2008 Achilli

- Hispanic American – 2008 Just

- Mexican – 2007 Peñaloza-Espinosa

- Mexican, Achilli, 2008

- Eskimo – Volodko, 2008

- Dogrib – Eskimo – Volodko, 2008

- Apache – Volodko, 2008

- Mexico and Central America – Eskimo – Volodko, 2008

- Apache – Volodko, 2008

- Ache and Guarani/Rio-das-Cobras and Katuana and Poturujara and Surui and Waiwai and Yanomama and Zoro – Fagundes 2008

- Waiwai, Brazil, Zoro, Brazil, Surui, Brazil, Yanomama, Brazil, Kayapo, Brazil, Arsario, Colombia, Cayapa, Ecuador, Kogui, Colombia – Fagundes 2008

- Arsario and Cayapa – Tamm 2007

- Kogui – Tamm 2007

- Colombia – Hartmann 2009

- Waorani tribe, Ecuador – Cardoso 2012

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (192 A2s with no subgroup),

- Inupiat people from Alaska North Slope – Raff 2015

- Ancestral locations found in March 2021 in the Haplogroup A project, Acadian AmerIndian Ancestry project and American Indian projects at Family Tree DNA include: Argentina, Brazil, California, Canada, Cuba, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, New Brunswick, Nicaragua, Ontario, Puerto Rico, Quebec, Washington State, Mississippi

- Tribes in 2021 include Algonquin and Choctaw.

Ancient A2

- Ancient remains from Lauricocha cave central Andean highlands – Fehren-Schmitz 2015

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- Chumash – Breschini and Haversat 2008

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Wari Culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Lima Culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Chancay culture, Pasamayo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Lauricocha culture, Lauricocha, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Tiwanaku culture, Lauricocha, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Paisley 5 Mile Point Caves, 11,000-10,800 YBP – Gilbert et al, 2008

- Manabi, San Ramon, Pichincha, Quito, Imbabura, Chimborazo, Riobamba, Tungurahua, Pillaro, Cotopaxi, Salcedo, Azuay and Cuenca in Ecuador, Native and Cayapa, also Peru, 6 ancient and several contemporary – Brandini, 2017

- Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvadore, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, Peru, Venezuela, in Canada – British Columbia, New Brunswick, Northwest Territory, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec, Vancouver Island, in the US – Alabama, Alaska, Caswell County, NC, Crawford County, PA, Michigan, Mississippi, tribes – Choctaw, Mi’kmaq – Haplogroup A2 Mitochondrial Project at Family Tree DNA, August 7, 2019

- Ancient samples (3) from San Nicolas Island, CA dating from approximately 2100-2400 BCE, Scheib et al, 2018

- Ancient samples (2) from Pampa Grande, Argentina, Candelaria culture dating from about 400 CE, Carnese et al 2010

- Ancient samples (2) from the Lauricocha, Highlands of Peru with 2 dating from about 6500-6700 BCE and one from 1600 BCE, Fehren-Schmitz 2015

- Ancient samples (5) from Lapa do Santo, Brazil dating from about 7500-7900 BCE, Posth 2018

- Ancient samples (2) from Arroyo Seco II, Argentina dating from about 5620 BCE, Llamas 2016

- Ancient sample from Pampas, Laguna Chica, Argentina dating from about 5000 BCE, Posth 2018

- Ancient samples (2) from Laranjal, Brazil dating from about 4600-5000 BCE, Posth 2018

- Ancient sample from Caleta Huelen, Chile daring from about 600-800 CD, Nakatsuka 2020

- Ancient samples (9) from Atajadizo, Dominican Republic dating from about 700 BCE (8 samples) and 1300 BCE (1), Fernandes 2020

- Ancient sample from Monserrate, Puerto Rico dating from about 800 CE, Fernandes 2020

- Ancient sample (3) from South Andros Island (Sanctuary Blue Hole,), Bahamas dating from about 1245 CE and 900 CE, Fernandes 2020

- Ancient samples (6) from Juan Dolio, Dominican Republic dating from about 1200-1250 CE, Fernandes 2020

- Ancient samples (3) from Andres, Dominican Republic dating from about 995 CE and 650 CE, Fernandes 2020

- Ancient sample from La Union, Dominican Republic dating from about 700 CE, Fernandes 2020

- Ancient sample from de Savaan, Curaco dating from about 1160 CE, Fernandes 2020

- Ancient sample from Canimar Abajo, Cuba dating from about 950 BCE, Fernandes 2020

- Ancient sample from Los Corniel (Rancho Manuel), Dominican Republic, dating from about 1150 CE. Fernandes 2020

- Ancient sample from Caba Rojo, Puerto Rico dating from about 1000 CE. Fernandes 2020

- Ancient samples (3) from La Caleta, Dominican Republic dating from about 1100 CE, Fernandes 2020

- Ancient sample from Cueva Juana near Cape of Samana, Dominican Republic dating from about 825 CE. Fernandes 2020

- Ancient sample from Paso del Indio, Puerto Rico dating from about 1100 CE. Nägele 2020

- Ancient samples (3) from Lavoutte (Cas-en-Bas), St. Lucia dating from about 1200-1300 CE. Nägele 2020

- Ancient sample from Los Indios, Puerto Rico dating from about 1350 CE.Nägele 2020

- Ancient sample from Guayabo Blanco (near Punto Brava), Cuba dating from about 600 BCE. Nägele 2020

- Ancient sample from Playa del Mango, Rio Cauto, Granma, Cuba dating from about 20 CE. Nägele 2020

- Ancient samples (2) from Cueva Calero (Matanzas), Cuba dating from about 400-500 CE. Nägele 2020

- Ancient samples (2) from Canimar Abajo, Cuba dating from about 500-600 CE. Nägele 2020

- Ancient sample from Cueva del Perico, Cuba dating from about 700 CE. Nägele 2020

- Ancient samples (2) from Paso del Indio, Puerto Rico dating from about 1000-1250 CE.Nägele 2020

- Ancient sample from Pica Ocho, Coast of Chile dating from about 1300 CE. Posth 2018

- Ancient sample from Arroyo Seco, Argentina dating from about 5800 BCE. Posth 2018

- Ancient sample (2) from the island Chumash, San Miguel Island, Canada dating from about 1830 CE and 1600-1800 CE. Scheib et al, 2018

- Ancient sample from mainland Chumash, Carpenteria, CA dating from about 400-550 CE. Scheib et al, 2018

- Ancient sample from island Chumash, Santa Cruz Island, CA dating from about 1500-1800 CE. Scheib et al, 2018

- Ancient sample from San Sebastian, Cusco, Highlands of Peru dating from about 1450 CE. Nakatsuka 2020

- Ancient sample from Huaca Pucllana, Lima Peru dating from about 700 CE. Nakatsuka 2020

- Ancient sample from El Brujo, Peru dating from about 1000 CE. Nakatsuka 2020

- Ancient sample from southwest of Buenos Aires, Argentina dating from about 400 BCE. Nakatsuka 2020

- Ancient samples (6) from the central Andes of southern Peru dating from about 300-1450 BCE. Fehren-Schmitz 2015

- Ancient sample from the middle Andes of southern Peru dating from about 1000 BCE. Fehren-Schmitz 2015

- Ancient samples from the Kotosh culture in La Galgada, Peru dating from about 2050 BCE, Llamas 2016

- Ancient sample from the Chinchorro culture in Camarones, Chile dating from about 1800 BCE, Llamas 2016

- Ancient sample from the Tiwanaku culture in Tiwanaku, Bolivia dating from between 500 and 1000 CE, Llamas 2016

- Ancient samples (4) from the Wari and Lima Cultures in Huaca Pucllana, Lima, Peru dating from between 500 and 1000 CE, Llamas 2016

- Ancient sample from the Chancay culture in Pasamayo, Peru dating from between 1000 and 1470 CE, Llamas 2016

- Ancient sample from the Inca culture in San Sebastian, Peru dating from about 1400 CE, Llamas 2016

- Ancient sample from the Late Central Andes culture from Cuncaicha, Highlands of Peru dating from 2250 BCE, Llamas 2016

- Ancient samples (2) from Pica, Chile dating to between 500 and 1000 BCE, Llamas 2016

- Ancient samples (5) from Checua, Colombia dating from 6000-7800 BCE and 2 samples dating from about 3000 BCE, Diaz-Matallana 2016

- Ancient sample from the Chinchorro culture in Arica, Chile dating from about 3800 BCE, Raghavan 2015

- Ancient sample from the Enoque culture from Toca do Enoque in Serra da Capivara, Piaui, Brazil, dating from about 3500 BCE, Raghavan 2015

- Ancient sample from Big Bar Lake, British Columbia, Canada dating from about 3600 BCE, Moreno-Mayar 2018

- Ancient samples (4) from the Wari era from Cochapata, Peru dating from about 600-1000 CE, Kemp 2009

- Ancient samples (3) from the Wari Era from Huari-MQ, Peru dating from about 1000-1450 BCE, Kemp 2009

- Ancient sample from the Caribbean culture from Santa Elena, Puerto Rico dating from between 900-1300 BCE, Fernandes 2020

- Ancient samples (4) found in Tibanica, Colombia from about 1000 BCE, Perez 2015

- Ancient sample from Tilcara, Quebrada de Humahuaca, Jujuy, Argentina dating from about 1100 BCE, Mendisco 2014

- Ancient sample from Banda de Perchel, Quebrada de Humahuaca, Jujuy, Argentina dating from about 1150 CE, Mendisco 2014

- Ancient samples (13) from Los Amarilloes, Quebrada de Humahuaca, Jujuy, Argentina dating from about 980-1467 CE, Mendisco 2014

- Ancient samples (2) from Fuerte Alto, Calchaqui Valley, Salta, Argentina dating from about 1000-1500 CE, Mendisco 2014

- Ancient sample from Tero, Calchaqui Valley, Salta, Argentina dating from about 1000-1500 CE, Mendisco 2014

- Ancient samples (2) from the Inca period from Esquina de Huajra (Quebrada de Humahuaca), Argentina dating from about 1500 CE. Russo 2017

- Ancient samples (4) from Doncellas, Argentina dating from about 1000-1450 CE, Postillone 2017

- Ancient sample from Casabindo, Argentina dating from about 1000-1450 CE, Postillone 2017

- Ancient sample from Agua Caliente, Argentina dating from about 1000-1450 CE, Postillone 2017

- Ancient sample from Doncellas, Argentina dating from about 1000-1450 CE, Postillone 2017

- Ancient samples (2) from the Athabaskan culture from Tochak McGrath, Upper Kuskokwim River, Alaska, one dating from about 1050-1400 CE, and one from about 550-900 CE, Flegontov 2019. This paper is fascinating – take a look.

- Ancient sample from Tequendama, Colombia dating from between 4000-5000 BCE, Delgado 2020

- Ancient sample from Ubate, Colombia dating from about 3600 BCE. Delgado 2020

- Ancient samples (4) from Aguazuque (Soacha), Colombia, two dating from about 1900 BCE, one from about 2600 BCE, and one from about 775 BCE. Delgado 2020

- Ancient sample from Canimar Abajo, Cuba dating from about 1100 BCE, Nägele 2020

- Ancient sample from Restigouche River, near the town of Atholville in northern New Brunswick, Canada dating from about 1500 CE. Raghavan 2015

- Ancient sample from the lnca Late Horizon from Chincha, Peru dating from about 1500 CE. Bongers 2020

A2a and A2b

- Paleo Eskimo, identified in only Siberia, Alaska and Natives from the American SW (Achilli 2013)

- Raff 2015 – Inupiat people from Alaska North Slope

- Ancient sample, Holas Island, Canada, about 2400 BCE,

A2a

- Aleut – 2008 Volodko

- Eskimo – Volodko, 2008

- Apache – Volodko – 2008

- Siberian Eskimo, Chukchi, Dogrib, Innuit and Naukan – Dryomov, 2015

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (2 A2a)

- Common among Eskimo, Na-Dene and the Chukchis in northeasternmost Siberia, Athabaskan in SW (Achilli 2013), circumpolar Siberia to Greenland, Apache 48%, Navajo 13%

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

Ancient A2a

- Ancient samples (3) from Ekven, Russia, from a 2000 year old Eskimo cemetery near Uelen on the easternmost spit of land in the Bering Strait, one sample dating from about 100 BCE, one from about 900 BCE and one from about 30 BCE, Sikora 2019

- Ancient samples (5) from Ekven, Russia, from a 2000 year old Eskimo cemetery representing the Old Bering Sea culture near Uelen on the easternmost spit of land in the Bering Strait, dating from about 700-1000 CE, Flegontov 2019

- Ancient sample from Kagamil Island Warm Cave, Aleutian Islands, Alaska dating from about 1600 CE, Flegontov 2019

- Ancient samples (2) from Uelen, Chukotka, Russia on the easternmost spit of land in the Bering Strait dating from about 1000 CE and about 250 CE, Flegontov 2019

- Ancient sample from the Palm Site (Cook Inlet) from the Alaskan Athabaskan culture dating from about 1850 CE, Scheib et al, 2018

- Ancient sample from Punta Candelero, Puerto Rico dating from about 158 CE, Nägele 2020

- Ancient samples (2) from Ekven, Russia, from a 2000 year old Eskimo cemetery representing the Old Bering Sea culture near Uelen on the easternmost spit of land in the Bering Strait, dating from about 800-1000 CE, Harney 2020

A2aa

- Waiwai and Poturujara tribes in Brazil Fagundes, 2008

- Peru – Brandini, 2017

A2ab

A2ac

- Chimborazo, Pallatanga, Riobana, Pichincha, Cayambe, Quito, Mejia in Ecuador, Mestizo and Cayapa – Brandini, 2017

- Hispanic – Just, 2015

- Colombia – Rieux, 2014

- Venezuela – Brandini, 2017

A2ac1

- Colombia, Cuba – Behar, 2012

- Colombia – HGDP

A2ac2

- Chimboro, Penipe, Santo Domingo, El Poste, Pichincha, Quito, Bolivar, Chimbo in Ecuador, Native Tsachila and Mestizo – Brandini, 2017

A2ad

A2ac

A2am

A2ar

- Guatemaula – Sochtig, 2015

A2a1

- Selkup and Innuit – Dryomov, 2015

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Ancient samples (2) from Ekven, Russia, from a 2000 year old Eskimo cemetery representing the Old Bering Sea culture near Uelen on the easternmost spit of land in the Bering Strait, dating from about 850 CE, Flegontov 2019

- Ancient sample from Tochak McGrath, Upper Kuskokwin River, Alaska from the Athabaskan culture dating from about 1225 CE, Flegontov 2019

- Ancient sample from Ekven, Russia, from a 2000 year old Eskimo cemetery representing the Old Bering Sea culture near Uelen on the easternmost spit of land in the Bering Strait, dating from about 3 CE, Sikora 2019

- Ancient sample from Ekven, Russia, from a 2000 year old Eskimo cemetery representing the Old Bering Sea culture near Uelen on the easternmost spit of land in the Bering Strait, dating from about 800 CE, Harney 2020

A2a2

Ancient A2a2

- Ancient sample from Ekven, Russia, from a 2000 year old Eskimo cemetery representing the Old Bering Sea culture near Uelen on the easternmost spit of land in the Bering Strait, dating from about 250 BCE, Sikora 2019

- Ancient sample from Ekven, Russia, from a 2000 year old Eskimo cemetery representing the Old Bering Sea culture near Uelen on the easternmost spit of land in the Bering Strait, dating from about 1150 CE, Flegontov 2019

- Ancient sample from Uelen, Chukota, Russia on the easternmost spit of land in the Bering Strait, dating from about 1150 CE, Flegontov 2019

A2a3

Ancient A2a3

- Birnirk (ancient sample,) Chukchi, Naukan, Innuit in Canada and Greenland – Dryomov 2015

- Ancient sample from Ulaanzuukh, Sukhbaatar, Mongolia dating from about 1200 CE, Jeong 2020

- Ancient sample from the Pucuncho Basin, Cuncaicha, Peru dating from about 2250 BCE, Nakatsuka 2020

- Ancient sample from the Cuncaicha Highlands, Peru dating from about 2230 BCE, Llamas, 2016

A2a4

A2a5

A2ab

A2ac

A2ac1

A2ad

A2ae

A2af

A2af1a

A2af1a1

A2af1a2

A2af1b1

A2af2

A2ag

- British Columbia, Tsimshian, ancient burial 152 Dodge Island, Canada – Cui 2013

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Ancient sample from Biggest of Lucy Islands, Alaska dating from about 3700 BCE, Cui 2013

- Ancient sample from Dodge Island, British Columbia, Canada shell midden site dating from about 900 BCE, Cui 2013

A2ah

- British Columbia, Dodge Island ancient burial 160a, Nisga’a, Kaigiani Haida, Tsimshian, Bella Coola – Ciu 2013

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Peru – Brandini, 2017

- Ancient sample from Quebrada de Humahuaca valley, Argentina dating from about 1450 CE, Russo 2018

- Puerto Rico, USA – Haplogroup A Project 2021

A2ai

A2ak

A2al

A2am

A2ao

- Ancient sample from Cuncaicha, Highlands of Peru dating from about 1420 CE, Posth 2018

A2ao1

A2ap

A2aq

A2ar

A2as

A2as1

A2at

A2at1

A2au

A2av

A2av1

- Pichincha, Quito, El Oro, Zaruma in Ecuador, Mestizo and Native Panzaleo, also Peru – Brandini, 2017

A2av1a

- Tungurahua, Pillaro, Ambato, Chimborazo, Riobamba in Ecuador, Mestizo and Native Panazaleo, also Peru – Brandini, 2017

A2aw

- Carchi, Tulcan, Carchi, Montufar San Gabriel in Eduador, Mestizo and Native Cayambe – Brandini, 2017

A2b

A2b1

A2c

A2c-C64T

A2d

A2d1

A2d1a

A2d2

A2e

A2f

A2f1

A2f1a

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- New Brunswick and Chippewa and Nova Scotia and Ojibwa and Mi’kmaq found in the Haplogroup A project at Family Tree DNA

- Mi’kmaq found in the Haplogroup A2 project at Family Tree DNA

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Cree, Ojibwa on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, Nova Scotia, Thunder Bay, Canada, Chippewa from Pembina Red Lake, MN,

A2f2

A2f3

A2g

- Achilli, 2008

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Hispanic – Parsons, Mexico – Kumar and Behar, Iberia – Hartman, Guatemala found in the Haplogroup A project at Family Tree DNA

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (5 A2g)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

A2g1

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Hispanic – Parsons, Mexico – Kumar, Asia – Hernstadt

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (3 A2g1)

- New Mexico, Athabascan heritage, private test at 23andMe

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

A2-G153A!

A2 – G16129A!

A2h

A2h1

A2i

A2j

A2j1

A2k

- Achilli, 2008

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Hispanic – Parsons, Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (4 A2k)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Pichincha, Manabi, Guayllabamba, Los Rios, quevedo, in Ecuador, Mestizo and Native Salasaca – Brandini, 2017

- Mexico – Kumar, 2011

- Mexico – Greenspan (FTDNA), 2011 direct submission

- Puerto Rico – Haplogroup A project 2021

A2k1

- Achilli, 2008

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Hispanic – Parsons

- Wayuu – Tamm, 2007

- Mexico – FTDNA

- Puerto Rico found in the Haplogroup A project at Family Tree DNA

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (5 A2k1)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Peru – Brandini, 2017

- Hispanic – Just, 2008

A2k1a

A2l

A2m

A2n

A2p

A2p1

A2q

A2q1

A2r

A2r1

A2t

A2-T16111C!

A2u

A2u1

A2u2

A2v

A2v1

A2v1a

A2v1b

A2v1-T152C!!!

A2w

A2w1

A2x

A2y

A2y1

- Chimborazo, La Moya, Imbabura, San Rafael, in Ecuador, Native Otavalo, Mestizo and Waorani, also Peru – Brandini, 2017

A2z

A2z1

- Peru – Brandini, 2017

- Puerto Rico – Behar, 2012

- Puerto Rico – HGDP

- Hispanic – Just, 2008

- Hispanic – Just, 2014

A2z2

A2-C64T

A2-C64T-A189G (please note that under Build 17, most of haplogroup A2 has been reassigned)

A2-C64T-T16111C! (please note that in Build 17, this haplogroup is now A2-T16111C!)

A3

A4 (Please note that in Build 17, people previously assigned A4 were reassigned to other haplogroups based on their mutations, including haplogroups A, A18, A2-T16111C!, A2-G153A!, A-T152C!, A-T152C!-A200G, A A2ao, A2q1, A12a and possibly others. Haplogroup A4 itself no longer exists.)

- Siberian founder of A2, not found in Americas – Kumar 2011

- Poland and Romania found in the Haplogroup A4 project at Family Tree DNA

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (2 A4)

- A4 is Native, found in Mexico, Colombia, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Honduras, Costa Rica and elsewhere – Estes 2015 – Haplogroup A4 Unpeeled – European, Jewish, Asian and Native American

- Chumash – Breschini and Haversat 2008

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

A4a (please note that in Build 17, A4a became A1)

- Kumar 2011 – Siberian founder of A2, not found in Americas

A4a1 (please note that in Build 17, A4a1 became A1a)

A4b (please note that in Build 17, A4b became A12a)

A4c (Please note that in Build 17, A4c became A13)

- Siberian founder of A2, not found in Americas – Kumar 2011

A5

A5a

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 A5a)

A6

A7

A8

A9

A10

A11

A12

A12a

- In Build 17, previous haplogroup A4b became A12a

A13

Haplogroup B

B

B1

B2

- Native, Beringian Founder Haplogroup – 2008 Achilli, 2007 Tamm

- Mexican – 2007 Peñaloza-Espinosa

- Quecha and Ache and Gaviao and Guarani/Rio-das-Cobras and Kayapo-Dubemkokre and Katuena and Pomo and Waiwai and Xavante and Yanomama – Fagundes 2008

- Ache, Paraguay, Gaviano, Brazil, Xavante, Brazil, Quechua, Bolivia, Guarani, Brazil, Kayapo, Brazil, Guarani, Brazil, Yanomama, Brazil, Cayapa, Ecuador, Coreguaje, Colombia, Ngoebe, Panama, Waunana, Colombia – Fagundes 2008

- Hispanic American – Just 2008

- Colombia – Hartmann 2009

- Mexican American – Kumar 2011

- Cayapa and Coreguaje and Ngoebe and Waunana and Wayuu and Coreguaje – Tamm 2007

- Pima – Ingman 2000

- Native American – Mishmar 2003

- Colombian and Mayan – Kivisild 2006

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Colombia – Hartman

- Yaqui – FTDNA

- Shown with European and Mexican and South American entry in the Haplogroup B project at Family Tree DNA

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (2 B2)

- Ancient remains from Lauricocha Cave central Andean highlands – Fehren-Schmitz 2015

- Ancient sample, central Alaska, Upper Sun River site from circa 11,500 before present – 2015, Tackney et al

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- Aymara, Atacameno, Mapuche, Tehuelche in Chile and Argentina, South America – de Saint Pierre, 2012

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Ychsma culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Lima culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Pica-Tarapaca culture, Pica-8, Chile – Llamas, 2016

- Inca culture, Pueblo Viejo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Chancay culture, Pasamayo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Lauricocha culture, Lauricocha, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Tiwanaku culture, Tiwanaku, Bolivia – Llamas, 2016

- Aceramic culture, Cueva Cadelaria, Mexico – Llamas, 2016

- Upward Sun River, Tackney 2015

- Ancient samples, high percent B2 published populations: Yakama, Wishram, N. Paiute/Shoshoni, Washo, Fremont (500-1500 YBP,) Tommy Site (850-1150 YBP,) Anasazi (1010-2010 YBP,) Navajo, Jemez, Hualapai, Pai Yuman, Zuni, River Yuman, Delta Yuman, Tohono O’odham (Papago), Akimal O’odham (Pima,) Quechan/Cocopa, Nahua-Atopan, Embera, Puinave, Curriperco, Ingano, Uungay, San Martin, Peruvian Highlanders (550-450 YBP,), Yacotogia 1187 YBP, Ancash, Arequpa, Chimane, Puno (Quecha,) Quechua 2, Aymara 2, Trinitario, Quebrada de Humahuaca, Atacamenos, Chorote, Gram Chaco – Tackney 2015 supplement 2

- Ancient samples, Sinixt, Quecha, Coreguaje, Waunana, Wayuu – Tackney 2015 supplement 1

- Paisley 5 Mile Point Caves, 11,000-10,800 YBP – Gilbert et al, 2008

- LatacungaCotopaxi, Angamarca, Loja, Ganil, Saquisili, Canar, Azogues, Pichincha, Quito in Ecuador, Mestizo and Native, also Peru, 5 ancient and several Mestizo – Brandini, 2017

- Washington State, Oregon, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Illinois, North Carolina, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Brazil – Haplogroup B project at Family Tree DNA August 2019

B2a

- Found just to the south of A2a, widespread in SW and found in one Chippewa clan, one Tsimshian in Canada and tribes indigenous to the SW, Mexico, possibly Bella Coola and Ojibwa, evolved in North America – Achilli 2008 and 2013,

- Chihuahua, Mexico – Achilli, 2013

- Found with Mexican entry and descended from Dorothee Metchiperouata b.c.1695 (Illinois) in the Haplogroup B project at Family Tree DNA

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (14 B2a)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

B2aa

B2aa1

B2aa1a

B2aa2

- Mexico – Behar, 2012

- Mexico – Kumar, 2011

B2ab

- Peru, ancient and contemporary – Brandini, 2017

- Bolivia, ancient sample – Llamas, 2016

B2ab1

B2ab1a

B2ab1a1

B2ac

B2ad

B2ae

B2ag

B2ag1

B2ah

B2a1

B2a1a

B2a1a1

B2a1b

B2a2

B2a3

B2a4

B2a4a

B2a4a1

B2a5

B2b

- Achilli, 2008

- Yanomama, Pomo, Xavante, Kayapo – Fagundes, Cayapa – Tamm

- Shown in Mexico and South America in the Haplogroup B project at Family Tree DNA

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (40 B2b)

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Yschsma culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Wari culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Lima culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Inca culture, Pueblo Viejo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Chancay culture, Pasamayo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Cayapa – Tackney 2015 supplement 1

- Loja, Tungurahua, Pichincha, Pedro vicente Malonado in Ecuador, Native, Mestizo and Native Saraguro, also Peru, ancient and contemporary – Brandini, 2017

- Pomo in California – Fagundes, 2008

- Xavante in Brazil – Fagundes, 2008

- Colombia – HGDP

- Hispanic – Just, 2015

- Bolivia – Taboada-Echalar, 2013

- Hoopa Tribe – private correspondence to Roberta Estes, August 2019

B2b1

B2b2

B2b2a

- Bolivia – Toboada-Echalar, 2013

B2b3

B2b3a

B2b4

B2b5

- Pichincha, Juan Montalvo, Cotopaxi, Mulalo, San Miguel de Los Bancos, Imbabura, Ibarra, Loja, Onocapa, Quito in Ecuador, Native Cayambe, Cayapa and Mestizo, also Peru and Venezuela – Brandini, 2017

B2b5a

B2b5a1

B2b5b

B2b5b1

B2b5b1a

B2b5b1a1

- Pichicha, Ruminaui, Loja, Linderos, Ganil, Onocapa, Bolivar, Pinato in Ecuador, Native, Native Quincha, Mestizo – Brandini, 2017

B2b6a

B2b6a1

- Pichincha, Quito, Ruminahui, Loja, Ganil in Ecuador, Native and Mestizo, also Peru – Brandini, 2017

B2b6a1a

- Chimborazo, Riobamba, Chimborazo, Colta, Cotopaxi, Salcedo, Loja, Onacapa, Loja, Ganil, Quito, Pichincha, Pujili, Machachi in Ecuador, Native Puruha, Native Quitu-Cara/Cayambe Mestizo and Native – Brandini, 2017

B2b6b

B2b6b1

B2b6b1a

- Loja, Gonzanama in Ecuador, Mestizo and Native, also Peru – Brandini, 2017

B2b7

B2b8

B2b8a

B2b9

B2b9a

B2b9b

B2b9c

- Los Rios, Babahoyo in Ecuador, Mestizo, also Peru, 2 ancient – Brandini, 2017

B2b10a

B2b10b

B2b11

B2b11a

B2b11a1

B2b11a1a

B2b11b

B2b11b1

B2b12a

- Morona-Santiago, Yaupi in Ecuador, Native Shuar, also Peru – Brandini, 2017

B2b12b

B2b13

B2c

- Achilli, 2008

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Hispanic – Parsons

- Asia – Herrnstadt

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (2 B2c)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Ottawa River, Canada, Fulton Co., Pennsylvania, Orange Co., New York, Martin Co., North Carolina and San Luis Potosi, Mexico – Haplogroup B project at Family Tree DNA in August 2019

B2c1

B2c1a

B2c1b

B2c1c

B2c2

B2c2a

B2c2b

B2d

B2e

B2f

B2g

B2g1

B2g2

B2h

B2i2

B2i2a1a

B2i2b

B2i2b1

B2j

B2k

B2l

- Peuhuenche, Mapuche, Huilliche, Mapuche ARG and Tehuelche Chile and Argentina, South America – de Saint Pierre, 2012

- Wintu tribe descendant, Wintu DNA Project at Family Tree DNA, August 2019

B2l1

B2l1a

B2l1a1

B2m

B2n

B2o

B2o1

- Loja, Quilanga, Chimborazo, El Altar in Ecuador, Mestizo – Brandini, 2017

B2o1a

- Bolivia – Taboada-Eschalar, 2013

B2p

B2q

B2q1

- Pichincha, Zambiza, Loja, Catacocha, Onacapa in Ecuador, Native and Mestizo, also Peru – Brandini, 2017

B2q1a

- Loja, Ganil, El Oro, Arenillas in Ecuador, Mestizo, also Peru – Brandini, 2017

B2q1a1

B2q1b

B2r (Phylotree V17)

B2s

B2t

B2u

B2v

B2w

B2y

B2y1

B2y2

B2z

B2z1

- Cotopaxi and Sigchos in Ecuador, Mestizo and Native Panzaleo (Quincha) – Brandini, 2017

B2z1a

B2-T16311C!

B4

B4a1a

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 B4a1a)

B4a1a1

- Found in skeletal remains of the now extinct Botocudos (Aimores) Indians of Brazil, thought to perhaps have arrived from Polynesia via the slave trade. Goncalves 2013, Polynesian motif,

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 B4a1a1) – full genome sequencing shows these remains to be entirely Polynesian, Malaspinas, 2015, Estes 2015.

- Note August 30, 2016 – Te Papa’s archival records dating back to 1883/84 indicate that a Māori skull and a Moriori skull were sent to the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro in the early 1880s. In 2013-14, the findings of DNA research which included samples of Botocudo Indians housed at National Museum in Rio de Janeiro indicated that two of the Botocudo ancestors had typical Polynesian DNA sequences. It seems likely that these two “Botocudo Indians” with Polynesian DNA are the Tupuna (ancestors) that were sent from the Wellington Colonial Museum (now Te Papa) in the 1880s.

B4a1a1a

- Found in skeletal remains of the now extinct Botocudos (Aimores) Indians of Brazil, thought to perhaps have arrived from Polynesia via the slave trade. Goncalves 2013, Polynesian motif – full genome sequencing shows these remains to be entirely Polynesian, Malaspinas, 2015, Estes 2015. See August 30, 2016 note for B4a1a1.

B4a1b

B4a1b1

B4b

B4b1

B4bd

B4c1b

B4f1

B4’5

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Shown as European and East Asian and Mexican and South America and Nicaragua and Guatemaula and Cuba and Pacific Islands and identified as Ho-Chunk and descended from Pistikiokonay Pushmataha, b. 1766 (Choctaw) and Eastern Cherokee and Chickasaw and Creek in the Haplogroup B project at Family Tree DNA

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (15 B4’5)

- Please note that not all B4’5 is Native

B5b2

- Native American branch of haplogroup B with roots in the Altai-Sayan Upland. Starikovskaya, 2005

B5b2a

B5b2a2

B5b3

B2e

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

B21

- Found in skeletal remains of the now extinct Botocudos (Aimores) Indians of Brazil, thought to perhaps have arrived from Polynesia via the slave trade, Goncalves 2013

Haplogroup C

C

C1

- Native – 2008 Achilli, 2007 Tamm

- Mexican – 2007 Peñaloza-Espinosa, Kumar 2011

- Poturujara – Fagundes 2008

- Hispanic American – Just 2008

- Arara do Laranjal and Quechua and Yanomama and Waiwai and Zoro – Fagundes 2008

- Waiwai, Brazil, Zoro, Brazil, Quechua, Bolivia, Arara, Brazil, Poturujara, Brazil – Fagundes 2008

- Native American – Mishmar 2003

- Warao – Ingman 2000

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (25 C1 with no subgroup)

- Remains from Wizard’s Beach in Nevada– Chatters, 2015

- Aymara, Atacameno, Mapuche, Huilliche, Kawesqar, Mapuche, Teheulche and Yamana in Chile and Argentina, South America – de Saint Pierre, 2012

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Tiwanaku culture, Tiwanaku, Bolivia – Llamas, 2016

- Wizard’s Beach, Nevada – Tackney, 2016

- High Percent C1 published populations: Norris Farms 700 YBP, Cecil (3600-2860 YBP,) Cook 2000 YBP, Hualapai, Delta Yuman, Akimal O’odham (Pima,), La Calenta (Tainos) (1330-320 YBP,) Arawaken, Guambiano, Desano, Movina, Ignaciano

C1a

C1b

- Beringian Founder Haplogroup – 2008 Achilli

- Wayuu – 2007 Tamm

- Pima, Mexico – Hartmann 2009

- Mexican American – Kumar 2011

- Quechua and Zoro and Arara and Poturujara – Fagundes 2008

- Peru – Tito

- Colombia – Zheng

- Samish on Guemes Island and Fidalgo Island, British Columbia, American Indian DNA Project, 2014

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (26 C1b)

- Central Alaska from circa 11,500 before present – 2015 Tackney et al

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- Mexico and Ecuador in the Haplogroup C project at Family Tree DNA

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Inca culture, Llullaillaco, Argentina – Llamas, 2016

- Ychsma culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Wari culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Lima culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Inca culture, Pueblo Viejo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Chancay culture, Pasamayo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Chullpa Botigiriayocc, Peru- Llamas, 2016

- Tiwanaku culture, Tiwanaku, Bolivia – Llamas, 2016

- Aceramic culture, Cueva Candelaria, Mexico – Llamas, 2016

- Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil – Gomez-Carballa 2015

- Upward Sun River, Alaska – Tackney, 2015

- Canary, Hispanic, Pima – Tackney 2015 supplement 1

- Pichincha, Quito, Chimborazo, Guamote, Cotopaxi, Salcedo, Machachi, Azuay, Cuenca, Loja in Ecuador, Mestizo, Native Quitu-Cara/Cayambe and Native Puruha, also in Peru, 7 ancient and 16 contemporary, Mestizo – Brandini, 2017

- Wintu tribal survivors, private correspondence to Roberta Estes, August 2019

C1b1

C1b1a

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa, 2015

C1b1b

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1bi

- Gomez-Carbala, 2015, Complete Mito Genome of 500 Year Old Inca Child Mummy

C1b2

- Hispanic – Parsons

- Peru – Tito

- Asia – Herrnstadt

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (27 C1b2)

- Achilli, 2008

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Puerto Rico and Taino in the Haplogroup C project at Family Tree DNA

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Peru – Gomez-Carballa 2015

- Lima in Peru, also Morona Santiago, Taisha, Loja, Pichincha, Quito in Ecudaor, Native Shuar, Native Cayambe, Mestizo – Brandini, 2017

C1b2a

C1b2a1

C1b2b

- Puerto Rico – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b3

- Achilli, 2008

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- Hispanic – Parsons

- Peru – Tito

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 C1b3)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Mexico, USA, Peru – Gomez-Carballa 2015

- Peru – Brandini, 2017

C1b4

- Achilli, 2008

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Puerto Rico in the Haplogroup C project at Family Tree DNA

- Hispanic – Parsons

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (6 C1b4)

- Durango, Mexico from American Indian DNA Project at Family Tree DNA (November 2015)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Puerto Rico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

- Peru – Brandini, 2017

C1b5

C1b5a

- Hispanic – Parsons

- Mexican – Kumar

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b5b

C1b6

- Yanomama – Fagundes

- Brazil – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b7

- Mexican – Kumar

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 C1b7)

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Mexico, Haplogroup C project at Family Tree DNA

- Mexico, Mitosearch

- Rumsen peoples, Monterey Mission, California – Breschini and Hversat

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b7a

C1b7a1

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b7b

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b8

C1b8a

C1b8a1

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b9

C1b9a

C1b10

C1b10a

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b11

C1b11a1

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b11b1

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b12

C1b12a

- Mexico, USA – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b13

- Found in skeletal remains of the now extinct Botocudos (Aimores) Indians of Brazil, thought to perhaps have arrived from Polynesia via the slave trade, Goncalves 2013

- Chilean and Kolla – de Saint Pierre, Dec. 2012

- Atacameno, Pehuenche, Mapuche, Huilliche, Kawesqar, Mapuche, Tehuelche and Yamana in Chile and Argentina, South America – de Saint Pierre, 2012

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Chile, Argentina – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b13a

C1b13a1

C1b13a1a

C1b13b

C1b13c

C1b13c1

C1b13c2

- Chile, Argentina – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b13d

C1b13e

C1b14

C1b11

C1b15

C1b15a

- Brazil – Gomez-Carballa 2015

C1b16

C1b17

C1b18

C1b19

- Peru – Gomez-Carballa 2015

- Peru, 9 ancient and 2 contemporary – Brandini, 2017

C1b20

C1b21

C1b21a

- Peru – Gomez-Carballa 2015

- Peru, 2 ancient and 2 contemporary – Brandini, 2017

C1b22

C1b23

- Loja, Tuncarta, Onacapa, Ganil, Catacocha in Ecuador, Native, Native Saraguro and Mestizo – Brandini, 2017

C1b24

C1b25

C1b26a

C1b26a1

C1b27

C1b28

C1b29

- Bolivar, Cotopaxi, Mana, Quito, Loja in Ecuador, Native and Mestizo – Brandini, 2017

C1ba

C1b-T16311C

C1c

- Beringian Founder Haplogroup – 2008 Achilli

- Arsario, Colombia – Fagundes 2008

- Kogui, Colombia – Fagundes 2008

- Kogui and Arsario

- Mexican American – Kumar 2011

- Kogui – Tamm 2007

- Hispanic – Parsons

- Canada – Achilli

- Canada – Behar

- Cherokee and Cuba in the Haplogroup C project at Family Tree DNA

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (34 C1c)

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Lima culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Inca culture, Pueblo Viejo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Hispanic, Kogui, Arsario – Tackney 2015 supplement 1

- Chimborazo, Riobamba in Ecuador, Mestizo, also in Peru, 4 ancient and 5 contemporary – Brandini, 2017

C1c1

- Achilli, 2008

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 C1c1)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Chancay culture, Pasamayo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Nasca culture, Juaranga, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Tiwanaku culture, Tiwanaku, Bolivia – Llamas, 2016

C1c1a

C1c1b

C1c2

C1c3

C1c4

C1c5

C1c6

C1c7

C1c8

C1c8-A19254G, C16114T

C1d

- Beringian Founder Haplogroup – 2008 Achilli

- Coreguaje – 2007 Tamm

- Coreguaje, Colombia – Fagundes 2008

- Tamaulipas and Guanajuato and Chihuahua and Kolla-Salta and Buenos Aires and Boyacá, Colombia and Mexico – Perego 2010

- Chihuahua, Mexico, Salta, Argentina – Perego 2010

- Mexican American – Kumar 2011

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (4 C1d)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Hispanic, Coreguaje – Tackney 2015 supplement 1

C1d-C194T

- Mexico, and Argentina and Colombia – Perego,

C1d1

- Warao, Venezuela – Ingman 2000

- Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil and Lima, Peru and Buenos Aires and Loreta, Peru and Imbabura, Ecuador and Mestizos in Colombia and Minas Gerais, Brazil and Cajamarca, Peru and Huanucu,Peru and Puca Puca, Peru and Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil and Chaco, Paraguay and Kolla-Salta and Piura, Peru and Huancavelica, Peru and Corrientes and Los Lagos, Chile and Oklahoma and Kuna Yala, Panama and Darien, Panama and Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua and Eduador and Uruguay and Nicaragua – Perego 2010

- Fagundes 2008

- Tamm, 2007

- Coreguaje – Tamm

- Warao – Ingman

- American – Kivisild

- Hispanic – Parsons

- Brazil – Rieux

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Loja, Ganil in Ecuador, Mestizo, also Lima in Peru and 1 ancient sample – Brandini, 2017

C1d1a

C1d1a1

C1d1b

- Argentina and Kolla-Salta and Diaguita-Catamarca and Buenos Aires and Rio negro and Corrientes and Flores, Uruguay – Perego 2011

- Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, Buenos Aires, Argentina, Loreto, Peru, Minas Gerais, Brazil, Cajamarca, Peru, Huánuco, Peru, Puca Pucara, Peru, Chaco, Paraguay, Huancavelica, Peru, Los Lagos, Chile, Panama – Perego 2010

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

C1d1b1

C1d1c

C1d1c1

C1d1d

- Buenos Aires and Rio Grande do Sul, Brzil and Uruguay and Argentina – Perego 2010

- Buenos Aires, Argentina, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, Uruguay – Perego 2010

- Coreguaje – Tamm

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Pichincha, Conocoto in Ecuador, Native Quitu-Cara – Brandini, 2017

C1d1e

C1d1f

- Imbabura, Pichincha, Ruminahui, Quito, Cotopaxi in Ecuador, Mestizo – Brandini, 2017

C1d2

C1d2a

C1d3

C1d-C194T

C1e

C2

- Mexican – 2007 Peñaloza-Espinosa

C2b

C4

- 2007 Tamm

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (4 C4 with no subgroup)

- Chippewa – White Earth Reservation, Minnesota – private test at 23andMe

- Inupiat people from Alaska North Slope – Raff 2015

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

C4a

C4a1

C4b

C4c

Beringian Founder Haplogroup – 2008 Achilli

C4c1

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Suswap – Malhi

- N American – Kashani

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 C4c1)

- Chippewa Cree, Jasper House, Alberta, Canada (1835), FTDNA American Indian Project

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

C4c1a

C4c1b

C4c2

C4e

Haplogroup D

D

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Choctaw and Korea and Japan and Mexico and Venezuela found in the Haplogroup D project at Family Tree DNA

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (7 D with no subgroup)

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Ychsma culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Lima culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Chile, Haplogroup D Project at Family Tree DNA, January 8, 2019

- Please note that not all haplogroup D without a subgroup is Native American

D1

- Native, Beringian Founder Haplogroup – 2008 Achilli

- Coreguaje – 2007 Tamm

- Mexican – 2007 Peñaloza-Espinosa

- Hispanic American – 2008 Just

- Mexican American – Kumar 2011

- North American – Henstadt 2008 and Achilli 2008

- Katuena and Poturujara and Surui and Tiryo and Waiwai and Zoro and Gaviao and Guarani/Rio-das-Cobras – Fagundes 2008

- Gaviao, Brazil, Surui, Brazil, Waiwai, Brazil, Katuena, Brazil, Poturujara, Brazil, Tiryo, Brazil – Fagundes 2008

- Karitiana, Brazil – Hartmann 2009

- Guarani – Ingman 2000

- Native American – Mishmar 2003

- Guarani and Brazilian and Que Chia and Pima Indian – Kivisild 2006

- British Colombia found in the Haplogroup D project at Family Tree DNA

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (59 D1)

- D1 from 12,000-13,000 skeletal remains found in the Yukatan, Chatters et al 2014, Chatters et al 2015

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- Chumash, Rumsen, Yokuts, Tubatulabal, Mono, Gabrielino – Breschini and Haversat 2008

- Aymara, Atacameno, Huilliche, Kawesqar, Mapuche, Yamana in Chile and Argentina, South America – de Saint Pierre, 2012

- Rio Negro, Argentina, Buenos Aires, Argentina, Tarapaca, Chile, Maule, Chile, Atacama, Chile, Mapuche, Argentina, Biobio, Chile, Cordoba, Argentina, Valparaiso, Chile – Bodner 2012

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Ychsma culture, Huaca Pucllana, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Inca culture, Pueblo Viejo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Chancay culture, Pasamayo, Peru – Llamas, 2016

- Loja in Eduador, Mestizo, also several Peru, Mestizo and 3 ancient samples

D1a

D1a1

D1a1a1

D1a2

D1b

D1c

D1d

D1d1

D1d2

D1f

- Kumar 2011

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Loja, Pichincha, quito, Cotopaxi, Cusubamba, Calvas in Ecuador, Mestizo and Native Panzaleo (Quincha), also Peru – Brandini, 2017

- Coreguaje of Colombia – Tamm, 2007

D1f1

D1f2

D1f3

D1g

- Found in skeletal remains of the now extinct Botocudos (Aimores) Indians of Brazil, thought to perhaps have arrived from Polynesia via the slave trade, Goncalves 2013

- Aymara, Pehuenche, Mapuche, Huilliche, Mapuche, Tehuelche, Yamana in Chile and Argentina, South America – de Saint Pierre, 2012

- New Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D1g1

D1g1a

D1g2

D1g2a

D1g3

D1g4

D1g5

D1g6

D1h

D1i

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D1i2

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D1j

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

D1j1a

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D1j1a1

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

D1k

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Mexico – HGDP

- Hispanic – Just, 2008

- Mexico – Kumar, 2011

D1k1

D1k1a

D1m

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D1n

D1o

D1p

D1q

D1q1

D1r

D1r1

D1s

D1s1

D1t

D1u

D1u1

D2

- Aleut, Commander Islands and Eskimo, Siberia – 2002 Derbeneva

- 2007 Tamm

- Mexican – 2007 Peñaloza-Espinosa

- Tlingit, Commander Island – Volodko 2008

- Inupiat people from Alaska North Slope, ancient Paleo-Eskimos – Raff 2015

- Miwok – Breschini and Haversat 2008

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D2a

- NaDene – 2002 Derbeneva

- 2008 Achilli

- Eskimo in Siberia – Tamm 2007

- Late Dorset ancient sample, Tlingit (Commander Island) – Dryomov 2015

- Inupiat people from Alaska North Slope – Raff 2015

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D2a1

- Aleut Islanders and northernmost Eskimos, Saqqaq Ancient sample, Middle Dorset ancient sample – Dryomov 2015

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D2a1a

- Aleut – 2008 Volodko

- Aleut – Dryomov 2015

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Commander Islands – 2008 Volodko (100%)

D2a1b

- Sireniki (Russian) Eskimo – Dryomov 2015

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D2a2

- Chukchi – Derenko, Ingman, Tamm and Volodko

- Eskimo – Tamm and Volodko

- Siberia – Derbeneva

- Eskimos and Chikchi – Dryomov 2015

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D2b

- 2007 Tamm

- Aleut 2002

- Derbeneva, Russia – Derenko

- Siberian mainland cluster – Dryomov 2015

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D2c

- Eskimo – 2002 Derbeneva

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D3

- Inuit – 2008 Achilli

- 2007 Tamm

- Inupiat people from Alaska North Slope (noted as currently D4b1a) – Raff 2015

- Ancient Neo-Eskimos, Kitanemuk, Kawaiisu – Breschini and Haversat 2008

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D3a2a

D3a2a

D4

- 2007 Tamm

- Cayapa, Ecuador – Fagundes 2008

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (2 D4)

- Chumash – Breschini and Haversat 2008

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4b1

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 D4b1)

D4b1a

- Inupiat people from Alaska North Slope (noted as formerly D3), ancient Neo-Eskimos – Raff 2015

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4b2a2

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 D4b2a2)

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4e1

- Mexican American – Kumar 2011

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4e1a1

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 D4e1a1)

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4e1c

- Kumar 2011 – found in Mexican Americans (2 sequences only)

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4g1

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4h1a

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4h1a1

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4h1a2

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4h3

- Beringian Founder Haplogroup – 2008 Achilli

- 2007 Tamm

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 D4h3)

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4h3a

- Veracruz, Mexico, Arequipa, Peru, Loreto, Peru, Ancash, Peru, San Luis Potosi, Mexico, Maranhao, Brazil – Perego 2009

- Mexican American – Kumar 2011

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (2 D4h3a)

- Raff and Bolnick, Nature February 2014 – Anzick’s haplogroup

- Remains from On Your Knees Cave in Alaska, Chatters, 2015

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

- Aymara, Mapuche, Huilliche, Kawesqar, Tehuelche, Yamana in Chile and Argentina, South America – de Saint Pierre, 2012

- Native American Mitochondrial

- DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- On Your Knees Cave, Alaska, 10,300 YPB – Lindo 2017

- Peru and Ecuador, Cayapa and Mestizo – Brandini, 2017

D4h3a1

- Coquimbo, Chile, O’Higgins, Chile, Coquimbo, Chile, Santiago, Chile, Los Lagos, Chile, Bio-Bio, Chile – Perego 2009

D4h3a1a

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4h3a1a1

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4h3a2

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

D4h3a3

- Chihuahua, Mexico, Tarahumara, Mexico, Nuevo Leon, Mexico – Perego 2009

D4h3a4

D4h3a5

- Maule, Chile, Los Lagos, Chile, Santiago, Chile – Perego 2009

- Equador and Peru – Brandini, 2017

D4h3a6

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

- Cotopaxi, Farahugsha in Ecuador, Native Panazleo (Quincha), also Peru – Brandini, 2017

D4h3a7

- British Columbia ancient sample 939, may be extinct – Ciu 2013

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4h3a8

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4h3a9

D4h3a11

D4j

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (2 D4j)

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D4j8

- Gran Chaco, Argentina – Sevini 2014

D5

D5a2a

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D5b1

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

D6

D7

D8

D9

D10

Haplogroup F

F1a1

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017 – Mexico in American Indian Project

Haplogroup M

M

- Discovered in prehistoric sites, China Lake, British Columbia – 2007 Malhi

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

M1

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017- Probably Native

M1a

M1a1b

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 M1a1b)

M1a1e

- USA – Olivieri

- Many Eurasian in Genbank

M1b1

M2a3

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 M2a3)

M3

M5b3e

M7b1’2

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 M7b1’2)

M9a3a

M18b

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

M23

M30c

M30d1

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 M30d1)

M51

Haplogroup X

X

- A founding lineage – found in ancient DNA Washington State – 2002 Malhi

- 2007 Tamm

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

X2

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

X2a

X2a1

X2a1a

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Sioux and USA – Perego

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 X2a1a)

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

X2a1a1

- Jemez and Siouian – Fagundes

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

X2a1b

X2a1b1

- USA – Perego

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

X2a1b1a

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Western Chippewa and Chippewa – Fagundes

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (2 X2a1b1a)

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

X2a1c

X2a2

- Navajo – Mishmar

- USA – Perego

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 X2a2)

- Manawan in Quebec, Newfoundland Island, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador – Haplogroup X Project at Family Tree DNA

- Estes X2a (2016)

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

X2b

- European – note that 2008 Fagundes removed a sample from their analysis because they believed X2b was indeed European not X2a Native

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (2 X2b)

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017

X2b-T226C

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 X2b-T226T confirmed Irish, not Native)

X2b3

X2b4

X2b5

- Not Native American – Cherokee DNA Project

X2b7

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017 – Not Native

X2c

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017 – not Native

X2c1

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017 – not Native

X2c2

X2d

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017- probably not Native

X2e1

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Behar notes two submissions at mtdnacommunity that are likely European

- 2 confirmed X2e1 from Valcea , Romania at Family Tree DNA

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017 – probably not Native

X2e2

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes, September 2014, kits F999912 and F999913

- Anzick Provisional Extract, Estes January 2015 – (1 X2e2)

- Native American Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, Estes, 2017 – probably not Native

X2g

- Identified in single Ojibwa subject – Achilli 2013

- Ojibwa – Perego

X2e

- Altai people, may have arrived from Caucus in last 5000 years

X2e1

X6

- Found in the Tarahumara and Huichol of Mexico, 2007 Peñaloza-Espinosa

MtDNA References

Mitochondiral genome variation and the origin of modern humans, Ingman et al, Natuer 2000, http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v408/n6813/full/408708a0.html

Mitochondrial DNA and the Peopling of the New World, Theodore Schurr, American Scientist, 2000, http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~tgschurr/pdf/Am%20Sci%20Article%202000.pdf

Brief Communication: Haplogroup X Confirmed in Prehistoric North America, Ripan Malhi et al, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2002, http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/34275/10106_ftp.pdf

Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in the Aleuts of the Commander Islands and Its Implications for the Genetic History of Beringia, Olga Derbeneva et al, American Journal of Human Genetics, June 2002, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC379174/

High Resolution SNPs and Microsatellite Haplotypes Point to a Single, Recent Entry of native American Y Chromosomes into the Americas, Zegura et al, Oxford Journals, 2003, http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/21/1/164.full.pdf

Ancient DNA – Modern Connections: Results of Mitochondrial DNA Analyses from Monterey County, California by Gary Breschini and Trudy Haversat published in the Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly, Volume 40, Number 2, (written 2004 although references are later than 2004, printed 2008)

Ancient individuals from the North American Northwest Coast reveal 10,000 years of regional genetic continuity by John Lindo et al, published in PNAS April 2017

Mitochondrial haplogroup M discovered in prehistoric North Americans, Ripan Malhi et al, Journal of Archaeological Science 34 (2007), http://public.wsu.edu/~bmkemp/publications/pubs/Malhi_et_al_2007.pdf

Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders, Erika Tamm et al, PLOS One, September 2007, http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0000829

Characterization of mtDNA Haplogroups in 14 Mexican Indigenous Populations, Human Biology, 2007

Achilli A, Perego UA, Bravi CM, Coble MD, et al. (2008) The Phylogeny of the Four Pan-American MtDNA Haplogroups: Implications for Evolutionary and Disease Studies. PLoS ONE 3(3): e1764. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001764 http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0001764

Complete mitochondrial genome sequences for 265 African American and US “Hispanic” individuals, Forensic Science Int. Genetics, 2 e45-e48, 2008, Just et al

Mitochondrial population genomics supports a single pre-Clovis origin with a coastal route for the peopling of the Americas, American Journal of Human Genetics, 82, 583-592, 2008 Fagundes et al

The Phylogeny of the Four Pan-American MtDNA Haplogroups: Implications for Evolutionary and Disease Studies, Achilli et al, PLOS, March 2008, http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0001764

Mitochondrial genome diversity in arctic Siberians with particular reference to the evolutionary history of Beringia and Pleistocenic peopling of the Americans, Natalia Volodko, et al, American Journal of Human Genetics, June 2008 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18452887

A Reevaluation of the Native American MtDNA Genome Diverstiy and Its Bearing on the Models of Early colonization of Beringia, Fagundes et al, PLOS One, Sept. 2008, http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0003157

Validation of microarray-based resequencing of 93 worldwide mitochondrial genomes, Hum. Mutat. 30, 115-122, (2009)H Hartmann et al

Distinctive Paleo-Indian migration routes from Beringia marked by two rare mtDNA haplogroups, Current Biology 19 1-8 (2009) Perego et al

Initial peopling of the Americas: A growing number of founding mitochondrial genomes from Beringia, Genome Research 20, 1174-1179, 2010 Perego et al

Large scale mitochondrial sequencing in Mexican Americans suggests a reappraisal of Native American origins, Kumar et al, Congress of the European Society for Evolutionary Biology, October 2011, http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/11/293

Large scale mitochondrial sequencing in Mexican Americans suggests a reappraisal of Native American origins, Kumar et al, 2011, Evolutionary Biology, http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/11/293/

Decrypting the Mitochondrial Gene Pool of Modern Panamanians, Ugo Perrego, et al, PLOS One, June 2012, http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0038337

An Alternative Model for the Early Peopling of Southern South America Revealed by Analyses of Three Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups, de Saint Pierre et al, 2012, PLOS

Rapid coastal spread of first Americans: Novel insights from South America’s Southern Cone mitochondrial genomes, Genome Research 22, 811-820, 2012, Bodner et al

Arrival of Paleo-Indians to the Southern Cone of South America: New Clues from Mitogenomes, de Saint Pierre et al, Dec. 2012, PLOS

Genetic uniqueness of the Waorani tribe from the Ecuadorian Amazon, Heredity 108, 609-615, 2012, Cardoso et al

Reconciling migration models to the Americas with the variation of North American native mitogenomes, Alessandro Achjilli et al, PNAS Aug. 2013, http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2013/08/08/1306290110.full.pdf+html

Ancient DNA Analysis of Mid-Holocene Individuals from the Northwest Coast of North America Reveals Different Evolutionary Paths for Mitogenomes, Yinqui Ciu et al, PLOS One, July 2013 http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0066948

Identification of Polynesian mtDNA haplogroup in remains of Botocudo Americndians from Brazil, Goncalves et al, 2013, PNAS http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3631640/

Late Pleistocene Human Skeleton and mtDNA Link Paleoamericans and Modern Native Americans” by James Chatters et al, May 2014, Science

Genetic roots of the first Americans, Raff and Bolnick, (February 2014), Nature

Late Pleistocene Human Skeleton and mtDNA Link Paleoamericans and Modern native Americans by Chatters, et al, Science, Vol 244, May 16, 2014

Two ancient genomes reveal Polynesian ancestry among the indigenous Botocudos of Brazil, by Malaspinas et al, Current Biology, November 2014

Botocudo Ancient Remains from Brazil, by Roberta Estes, July 2015

Two contemporaneious mitogenomes from terminal Pleistocene burials in eastern Beringia, Tackney et al, 2015, PNAS

The complete mitogenome of 500-year old Inca child mummy, 2015, Nature, Gomez-Carballa et al

Does Mitochondrial Haplogroup X Indicate Ancient Trans-Atlantic Migration to the Americas? A Critical Re-Evaluation, 2015, PubMed, Raff and Bolnick

Mitochondrial diversity of Iñupiat people from the Alaskan North Slope provides evidence for the origins of the Paleo- and Neo-Eskimo peoples by Raff et al, (April 17, 2015) American Journal of Physical Anthropology http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajpa.22750/

http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2015-04/nu-dsa042715.php

Mitochondrial genome diversity at the Bering Strait area highlights prehistoric human migrations from Siberia to northern North America – Dryomov et al, European Journal of Human Genetics, 2015

MtDNA Haplogroup A10 Lineages in Bronze Age Samples Suggest That Ancient Autochthonous Human Groups Contributed to the Specificity of the Indigenous West Siberian Population by Pilipenko, et al, PLOS One, 2015

A Reappraisal of the early Andean Human Remains from Lauricocha in Peru by Fehren-Schmitz et al, PLosS ONE 10 (6)(2105)

Ancestry and affiliations of Kennewick Man by Rasmussen et al, Nature, June 18, 2015

Ancient mitochondrial DNA provides high-resolution time scale of the peopling of the Americas, Llamas et al, Science Advances April 1, 2016 Vol. 2 No. 4, e1501385 http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/2/4/e1501385

Native American Haplogroup X2a – Solutrean, Hebrew or Beringian?, 2016, Estes

X2b4 is European, Not Native American, Estes, September 2016

‘Human mitochondrial genomes reveal population structure and different phylogenies in Gran Chaco (Argentina)’ by Sevini, F., Vianello, D., Barbieri, C., Iaquilano, N., De Fanti, S., Luiselli, D., Franceschi, C. and Franceschi, Z., sequences submitted to GenBank in January 2016 from 2014 unpublished paper

Archaeogenomic evidence reveals prehistoric matrilineal dynasty by Kennett et al, 2017, Nature Communications

New Native American Mitochondrial Haplogroups by Roberta Estes, March 2, 2017

DNA from Pre-Clovis Human Coprolites in Oregon, North America by M. Thomas P. Gilbert et al, published in Science May 9, 2008

The Paleo-Indian Entry into South America According to Mitogenomes by Brandini, et al, Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 35, Issue 2, February 2018, Pages 299–311

Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in Indigenous Populations of the Southern Extent of Siberia, and the Origins of the Native American Haplogroups by Elena B. Starikovskaya et al, Annals of Human Genetics, January 2005 (only haplogroup B5 posted above)

Locals, resettlers, and pilgrims: A genetic portrait of three pre‐Columbian Andean populations. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Baca, M., Molak, M., Sobczyk, M., Węgleński, P., & Stankovic, A. (2014). 154(3), 402-412

“Brief communication: Molecular analysis of the Kwäday Dän Ts’ finchi ancient remains found in a glacier in Canada.” Monsalve, M. Victoria, et al., American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists 119.3 (2002): 288-291

Ancient DNA reveals kinship burial patterns of a pre-Columbian Andean community, Baca, M., Doan, K., Sobczyk, M., Stankovic, A., & Węgleński, P. (2012) BMC genetics, 13(1), 30.

Ancient human parallel lineages within North America contributed to a coastal expansion. Scheib, C. L., Li, H., Desai, T., Link, V., Kendall, C., Dewar, G., … & Kerr, S. L. (2018). Science, 360(6392), 1024-1027.

Paleogenetical study of pre‐columbian samples from Pampa Grande (Salta, Argentina), Carnese, F. R., Mendisco, F., Keyser, C., Dejean, C. B., Dugoujon, J. M., Bravi, C. M., … & Crubézy, E. (2010), American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, 141(3), 452-462

A re-appraisal of the early Andean human remains from Lauricocha in Peru. Fehren-Schmitz, L., Llamas, B., Lindauer, S., Tomasto-Cagigao, E., Kuzminsky, S., Rohland, N., … & Nordenfelt, S. (2015), PloS one, 10(6), e0127141.

Reconstructing the deep population history of Central and South America. Posth, C., Nakatsuka, N., Lazaridis, I., Skoglund, P., Mallick, S., Lamnidis, T. C., … & Broomandkhoshbacht, N. (2018), Cell, 175(5), 1185-1197.

Ancient mitochondrial DNA provides high-resolution time scale of the peopling of the Americas. Llamas, B., Fehren-Schmitz, L., Valverde, G., Soubrier, J., Mallick, S., Rohland, N., … & Romero, M. I. B. (2016). Science advances, 2(4), e1501385.

A Paleogenomic Reconstruction of the Deep Population History of the Andes. Nakatsuka, N., Lazaridis, I., Barbieri, C., Skoglund, P., Rohland, N., Mallick, S., Posth, C., et al. (2020), Cell, 181 (5), 1131-1145.e21.

A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean. Fernandes, D. M., Sirak, K. A., Ringbauer, H., Sedig, J., Rohland, N., Cheronet, O., … & Adamski, N. (2020), bioRxiv

Genomic insights into the early peopling of the Caribbean. Nägele, K., Posth, C., Orbegozo, M. I., de Armas, Y. C., Godoy, S. T. H., Herrera, U. M. G., … & Laffoon, J. (2020). Science.

El análisis genético de paleo-colombianos de Nemocón, Cundinamarca proporciona revelaciones sobre el poblamiento temprano del Noroeste de Suramérica. Díaz-Matallana, M., Gómez Gutiérrez, A., Briceño, I., & Rodríguez Cuenca, J. V. (2016). Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. Ex. Fis. Nat., 40(156), 461-483.

Genomic evidence for the Pleistocene and recent population history of Native Americans, Raghavan, M., Steinrücken, M., Harris, K., Schiffels, S., Rasmussen, S., DeGiorgio, M., … & Eriksson, A. (2015). Science, 349(6250).

Early human dispersals within the Americas. Moreno-Mayar, J. V., Vinner, L., de Barros Damgaard, P., De La Fuente, C., Chan, J., Spence, J. P., … & Rasmussen, S. (2018). Science, 362(6419).

Genetic continuity after the collapse of the Wari empire: Mitochondrial DNA profiles from Wari and post‐Wari populations in the ancient Andes. Kemp, B. M., Tung, T. A., & Summar, M. L. (2009). American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, 140(1), 80-91

Aportes genéticos para el entendimiento de la organización social de la comunidad Muisca Tibanica (Soacha, Cundinamarca). Pérez, L., 2015. Ph.D. Dissertation, Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia.

Genetic diversity of a late prehispanic group of the Quebrada de Humahuaca, northwestern Argentina. Mendisco, F., Keyser, C., Seldes, V., Rivolta, C., Mercolli, P., Cruz, P., … & Ludes, B. (2014). Annals of Human Genetics, 78(5), 367-380.

Linajes mitocondriales en muestras de Esquina de Haujra (Jujuy, Argentina): Aportes al estudio de la ocupación incaica en la región y la procedencia de sus habitantes. Russo, M. G., Gheggi, M. S., Avena, S. A., Dejean, C. B., & Cremonte, M. B. (2016).

Linajes maternos en muestras antiguas de la Puna jujeña: Comparación con estudios de la región centrosur andina. Postillone, M. B., Fuchs, M. L., Crespo, C. M., Russo, M. G., Varela, H. H., Carnese, F. R., … & Dejean, C. B. (2017). Revista Argentina de Antropología Biológica, 19(1), 3.