According to the first census taken in Acadia, now Nova Scotia, in 1671, Catherine LeJeune was born about 1633.

While the census doesn’t tell us where Catherine was born, any French Acadian settler born before 1636, when the first Acadian families arrived in La Hève with Isaac Razilly, was assuredly born in France.

Furthermore, Catherine had a sibling, Edmee LeJeune, who also appeared in that census, married to Francois Gautrot. Edmee was born about 1624 and was married about 1644, based on her children’s ages. We know that Francois Gautrot was in Acadia prior to 1650, because he signed an attestation confirming the accomplishments of Charles Menou d’Aulnay, who died in 1650 – so they were clearly living in Port Royal by that time.

We also know that Francois Gautrot was granted land along the waterfront adjacent the fort in Port Royal, so was probably one of the earliest settlers and arrived in Port Royal with d’Aulnay. The land was expropriated from his descendants in 1705 to extend the original fort. Francois and Edmee were married about the time the Acadians would have settled at Port Royal, but Catherine LeJeune, the younger sister, and Francois Savoie didn’t marry until several years later.

We know that Catherine and Edmee were sisters, thanks to both mitochondrial DNA results and later dispensations granted by the priest when their descendants married.

This, of course, strongly suggests that both girls arrived as children with their parents between 1636, when the first French families arrived, and 1644, when Edmee married. Their parents had died before the 1671 census.

Pull up a chair, because this is about to get good!

Parent Confusion

Because absolutely nothing is straightforward about Acadian genealogy…

There is a male LeJeune, Pierre, born about 1656, who married Marie Thibodeau. They first lived in Port Royal in 1678, but by 1693, they lived at or near La Hève, the original seat of Acadia. Pierre’s brother was Martin LeJeune, born about 1661, who married a Native woman.

Their father was reportedly Pierre LeJeune, born about 1627, who reportedly married a Doucet female. He was probably granted land at La Hève because both of his sons, Pierre, born about 1656, and Martin, born about 1661, are found living side-by-side there in the 1686 census.

Notice words like “probably” and “reportedly.”

Pierre, the father of the brothers, Pierre and Martin LeJeune, is only specifically named after the 1755 deportation when their descendants, in a 1764 declaration at Belle-Ile-en-Mer, France stated, “Marguerite LeJeune was born at Port Royal in 1698 of Pierre and Marie Thibodault of Port Royal. Pierre LeJeune was issue of another Pierre who came from France and married at Port Royal, died there.” Please also note that the Belle-Ile-en-Mer declatations, in other cases, have been later proven to be in error. They were given from memory 3 or 4 generations and a century or more after the original Acadians arrived in order to provide the French government information about the origins of the Acadian refugees who found themselves back in France and in dire need.

I’m referring to Pierre, the father, as “the elder” and Pierre, Martin’s brother, as “the younger” for these discussions.

Based on the birth years of Pierre the younger, about 1656, and Martin, about 1661, Pierre the elder would have been born about 1627, or so. French men typically married when they were about 30. This also presumes that Pierre the younger was the oldest child of Pierre the elder, which may not be the case, so Pierre the elder may have been born significantly before 1627, but probably not after.

If, in fact, Pierre the elder, born about 1627, is the father of Pierre and Martin, he cannot be the father of Catherine, born about 1633, and Edmee, born about 1624. Pierre the elder could possibly be their brother, based only on birth years plus the same surname, but no additional information.

Furthermore, given Edmee’s birth about 1624, and Martin’s birth about 1661, a span of 37 years, Catherine and Edmee, and Pierre the younger (born about 1656) and Martin cannot be full siblings. They could potentially be half-siblings.

Due to the same surname, and such a limited number of families, I, along with the rest of Acadian researchers, have been trying to connect the dots.

What’s more logical is that Catherine and Edmee are siblings to Pierre the elder born about or before 1627, but lack of a marriage dispensation granted for their descendants suggests otherwise. Dispensations of consanguity were granted by the church allowing cousins of varying levels to marry with the church’s blessing.

For a long discussion, please refer to the link titled, “A Closer Look at Some of the Records” in the sidebar on Lucie LeBlanc Consentino’s site, here.

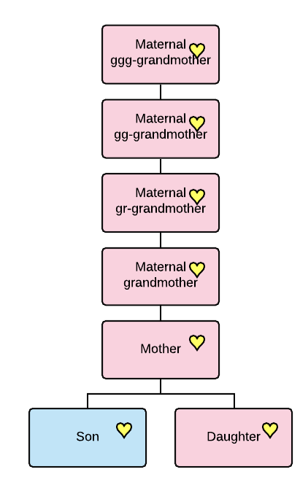

I freely admit, I had a difficult time wrapping my head around all of this, so I made a chart.

There were clearly three LeJeune founders in Acadia, one way or another. Yes, I said three. There’s more to the story.

Click to enlarge any image.

Our Catherine LeJeune is shown at right, highlighted in yellow, with her family line marked in green.

Pierre, the younger, with his father, Pierre the elder, is marked in apricot. His brother, Martin, is not shown but would be apricot too.

A third person, Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard, born about 1659, and who married Francois Joseph about 1684, is another player in this mix as well. She is found in the 1693 census in Port Royal, but not before. They are listed two doors from Germain Savoie, son of Catherine LeJeune and Francois Savoie. In 1698, Jeanne LeJeune has remarried to Jean Gaudet, and had one child, and by 1708 she too was living in La Hève.

Whoever Jeanne LeJeune’s father was, he was clearly an early settler, because he married a Native woman, as reflected in the marriage record of Jeanne’s daughter, Catherine Joseph, in 1720, where her mother is noted as “of the Indian Nation.” This is also confirmed by mitochondrial DNA testing of their matrilineal descendants which produced Native American haplogroup A2f1a.

Our Catherine Lejeune and Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard do not share a mother, as Catherine and Edmee’s mitochondrial DNA is haplogroup U6a7a1a, European, not Native.

Furthermore, by inference, based on the lack of Catholic religious dispensations granted to cousins, Pierre LeJeune the elder is not the father of Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard, even though both she and Pierre LeJeune the younger share the dit name of Briard. That could reflect back to a common French location for both people or a more distant family relationship. Stephen A. White, retired Acadian genealogist at Moncton, has concluded that Pierre LeJeune the elder married an unknown Doucet female, so not Native.

Jeanne’s LeJeune dit Briard’s line is noted in our chart blue, and her great-granddaughter, Martine Roy, bolded in red, married Pierre LeJeune the younger’s grandson, Joseph LeJeune, also bolded in red, in Louisbourg in 1754, with no dispensation recorded by the priest.

- If Jeanne LeJeune and Pierre the younger were siblings, then Joseph and Martine would have been 2C1R, and the priest’s dispensation would have been 3-4.

- If Jeanne LeJeune and Pierre the younger were first cousins, meaning they shared grandparents, then Joseph and Martine would have been 3C1R, and the dispensation would have been a 4-5, so no dispensation was needed at that distance.

- According to White, the priest at Louisbourg knew the families, and other family members were present, so if these people had needed a dispensation, they would have received one. It wasn’t simply overlooked.

Now, moving to Catherine LeJeune whose grandson, Nicolas Prejean married Euphrosine Labauve in 1760 at St. Servan in Saint Malo, France, also with no dispensation.

- If Pierre the elder and Jean LeJeune (yet another player and possible father of Catherine and Edmee) were siblings, then Nicolas and Euphrosine would have been 3C and the dispensation would have been 4-4.

- If Pierre the elder and Jean LeJeune (possible father of Catherine and Edmee) were first cousins, sharing grandparents, then no dispensation would have been necessary for Nicolas and Euphrosine.

Even though these unfortunate people had been expelled from Acadia and wound up in France, there were a significant number of other Acadian families who settled in the same location, creating a community, having suffered the same fate. If the couple had needed a dispensation, they would have received one.

This leads us to the conclusion that:

- Pierre LeJeune the younger is not the sibling of Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard, even though they are both shown with the same dit name and location.

- Pierre LeJeune the elder is not the sibling of Jeane LeJeune dit Briard, because Martine and Joseph would have required a 4-4 dispensation.

- Pierre LeJeune the elder and Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard could have been first cousins, because no dispensation would have been required.

- Pierre LeJeune the elder is not the sibling of Catherine LeJeune’s father, because Euphrosine and Nicolas would have required a 4-4 dispensation.

- Pierre LeJeune the elder could have been the first cousin of Catherine LeJeune’s father, because no dispensation would have been needed.

- Catherine LeJeune (born c 1633), her sister Edmee (born c 1624) and Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard (born c 1659) are not full siblings either, because Jeanne LeJeune dit Briard’s mother was Native American and Catherine and Edmee’s mother was European.

It’s also worth noting that while Jeanne LeJeune and both Pierre the younger and Martin LeJeune are noted in at least one record as “dit Briard,” neither Catherine nor Edmee ever are. Briard means a person who is from Brie, but could also have meant something else.

Who is Jean LeJeune?

On the chart, you might have noticed Jean LeJeune noted with a “?” as the potential father of Catherine LeJeune, which means he would have been Edmee LeJeune’s father as well.

Who is Jean LeJeune and where did he come from? That’s the burning question, of course.

White writes (bolding mine):

Jean Lejeune was one of the early settlers of Acadia. This is known from the fact that his heirs received one of the early land grants at Port-Royal. This grant is mentioned in the “Schedule of the Seigniorial Rents” that was drawn up in 1734, after the British Crown had purchased the seigneurial rights in that area (Public Record Office, Colonial Office records, series 217, Vol. VIL, fol. 90-91). The rents list shows the names of the first grantees of each parcel of land, as well as the names of those who were in possession in 1734. In some cases it is obvious that the latter belonged to the same family as the former, but in the case of the parcel allotted to Jean Lejeune’s heirs it is just as apparent that the tenancy had heen sold. No record of the original grant has survived, but there are indications that it had been made early in the colony’s history. It is enrolled along with grants that were made to Barnabé Martin and Francois Savoie. Both of these men were dead by the time of the 1686 census, so the grants must have been made before then. What’s more, Jean Lejeune had likely been dead for quite some time by 1686, because this grant could have dated back to any time after the retrocession of Acadia to the French in 1670 pursuant to the Treaty of Breda.

One can only speculate about how old Jean Lejeune’s heirs might have been when they received their grant, but it is likely that their forebear was a contemporary of the Pierre Lejeune who is mentioned in Claude Pitre’s deposition at Belle-fle-en-Mer in 1767 as the father of the Pierre Lejeune who married Marie Thibodeau. This deposition, by the way, is the only record that mentions the elder Pierre’s given, name. It also specifies that the elder Pierre came to Acadia from France, which rules out any possibility that he had any Native American blood. But this deposition does not preclude the possibility that the elder Pierre might have arrived from France with one or more siblings, including at least one brother.

For Catherine LeJeune, who married Francois Savoie, this is very nearly a smoking gun.

Very rarely did a single man set up a household.

Not only was a similar grant made to Francois Savoie, at BelleIsle, this suggests that the date of that grant was probably after their marriage around 1651 or 1652.

Furthermore, in the first Acadian census, in 1671, Catherine LeJeune and Francois Savoie are living on the same land with their daughter and son-in-law. Their neighbor is Pierre Martin, age 70, who lives beside three Martin family members, then two doors away we find Edmee LeJeune married to Francois Gautrot.

So, thanks to White, we have a Jean LeJeune who was granted land at BelleIsle along with Francois Savoie, who married Catherine LeJeune. The Savoie land has been located, which I wrote about in Francois Savoie’s Homestead Rediscovered.

Were Catherine and Edmee LeJeune the heirs of Jean LeJeune who were eventually granted the land at BelleIsle? Does that explain why they are living among the BelleIsle families?

Additional documents are unlikely to be found. Alexandre LeBorgne, Sieur de Belle-Isle, who began granting land around 1668 when he became Governor of the colony, destroyed those records to cover his incompetence.

Given that Jean LeJeune was granted land, and he was deceased by 1671, that puts both the grant date and his death sometime between 1668 and 1670 – unless d’Aulnay granted that land before his death in 1650 or before the falling of Acadia to the English in 1654.

It’s also possible that Jean LeJeune has been given posession of the land by d’Aulnay, but the official grant wasn’t made until later, and he was deceased by then, so it went to his heirs.

Christian Boudreau, in his thesis notes, provides additional information found in the “Schedule of the Seignorial Rents for one Whole Year Payable Yearly by the Inhabitants Within the Banlieu of the Fort of Annapolis Royal in His Majesties Province of Nova Scotia on the First Day of January for which they stand annually De to His Majesties Revenue”. Chris notes that the importance of the information enclosed in a letter dated May 10, 1734, is that the original grantees of a plot of land location in the region of “Bellisle” by Annapolis Royal were “the heirs of John Le Jeune” and the men who posessed the land in 1734 were Alexander Hebert and Michel Richards, but they don’t appear to be either descended from or related to Jean LeJeune.

We have a 1733 map of the region, but it only has village names, not individual names. The only Michel Richard of the right age in the right place in 1734 was married to a Marie Madeleine Blanchard and was probably living at BelleIsle where the Blanchards lived. However, the original Richard land, two generations earlier, was across the river from BelleIsle.

Alexandre Hebert was married to Marie Dupuis whose family lived at or near BelleIsle too. The original Hebert land was also across the river, near Bloody Creek. However, by 1734, the original LeJeune land, granted to Jean’s nameless heirs before Jean’s death, prior to the 1671 census, could well have been sold multiple times. I also wonder if the Richard and Hebert men each owned pieces of it, or owned it jointly.

The only things we know for sure about Jean LeJeune are:

- That he or his heirs received land at BelleIsle

- Jean was deceased by 1671

- If Catherine and Edmee were his daughers, they were both born in France

- If he is their father, Jean would have been born about 1595, or possibly earlier

- The family arrived between 1636 and 1644 when Edmee married

It’s also possible that, rather than being Catherine and Edmee’s father, Jean could have been their sibling. If he were unmarried, he would probably not have been granted land.

Regardless, by 1671, there is no trace of Jean LeJeune, or of a widow, or of children other than Catherine and Edmee, assuming they are his daughters.

I believe that’s the most likely explanation, but it’s far from conclusive.

Early Acadia

The first Acadian colonists settled in La Hève, on the southern coast of Acadia, in 1632, with Isaac Razilly leading the expedition that was focused on establishing a trading port. We know families arrived in 1636, and could have been a few in 1632. .

The LeJeune family could have arrived with the first or second group of families. If so, Catherine would have been just a baby. Mathieu Martin was reportedly the first Acadian child born in Acadia, and he was born about 1634.

Razilly died in 1635, and within a couple of years, Charles Menou d’Aulnay was appointed Governor of Acadia. He moved the Acadian colonists to Port Royal from La Hève as a group in the late 1630s and early 1640s.

By 1640, Port Royal was the seat of Acadia, and d’Aulnay set about having the swamps at BelleIsle drained so that the land could become salt-free, productive farmland, which took about 3 years after the land was dyked. BelleIsle, 1500 acres, was a HUGE area to dyke.

BelleIsle is the location where the Martin and Savoie families both settled, and it stands to reason that Jean LeJeune did too.

We don’t know when the LeJeune sisters arrived with their parents, whoever they were, but given that Catherine’s older sister, Edmee, married a local man, Francois Gautrot, either a craftsman or a soldier, around 1644, the family had assuredly arrived in Acadia by that time.

The LeJeune family may have first settled at La Hève, then moved with the rest of the Acadians to Port Royal, or they could have arrived in Port Royal with Charles Menou d’Aulnay around 1642 when he obtained financing and a ship from a La Rochelle financier, transporting additional families.

Based on a journal maintained by Nicolas Denys, we know that by 1654, when Acadia would fall to the English, there were about 270 residents at Port Royal, and that many settlers had moved upriver.

“There are numbers of meadows on both shores, and two islands which possess meadows, and which are 3 or 4 leagues from the fort in ascending. There is a great extent of meadows which the sea used to cover, and which the Sieur d’Aulnay had drained. It bears now fine and good wheat, and since the English have been masters of the country, the residents who were lodged near the fort have for the most part abandoned there houses and have gone to settle on the upper part of the river. They have made their clearings below and above this great meadow, which belongs at present to Madame de La Tour. There they have again drained other lands which bear wheat in much greater abundance than those which they cultivated round the fort, good though those were. All the inhabitants there are the ones whome Monsieur le Commandeur de Razilly had brought from France to La Have; since that time they have multiplied much at Port Royal, where they have a great number of cattle and swine.”

This golden nugget of information reveals a great deal about life in Acadia. The Great Meadow is BelleIsle, and Madame de La Tour is d’Aulnay’s widow.

He mentions that the residents have cleared the land below and above the meadow, and that d’Aulnay had the meadow drained. Are the residents clearing land above and below the meadow because the Martin, Savois and LeJeune heirs are already farming there?

Note that Denys said that, “all the inhabitants there are the ones whome…Razilly brought from France to La Hève.”

This tells us that Catherine LeJeune would have arrived as a small child, probably by 1635, and would have retained absolutely no memory of France.

Catherine was first-generation Acadian and lived her life on the shores of the Atlantic, on a new frontier.

She may or may not have remembered La Hève. They would have relocated to Port Royal when she was someplace between 3 and 7, building a new home along the Rivière Dauphin, probably at BelleIsle.

While they may have first settled in Port Royal briefly, while they got their bearings or built a cabin, it’s telling that many of the other early settlers obtained land that was expropriated in 1702-1705 when the fort was expanded. Neither Francois Savoie, Jean LeJeune, nor Barnabas Martin held land by the fort, although Barnabas married into the Pelletret family who did.

I’d wager that these families began draining the swamps immediately, recognizing the value of this prime real estate for farming.

They would have had first choice and were the first families to settle at BelleIsle. They established a village above BelleIsle Marsh.

The Savoie Land at BelleIsle

I wrote about the discovery of the Savoie homesteads and village at BelleIsle in the article titled, Francois Savoie’s Homestead Rediscovered.

I won’t repeat that information here, but I saved one of the goodies for Catherine’s article.

Several years ago, now-deceased Acadian artist Claude Picard created a wonderful print of the Savoie homestead based upon known homestead locations thanks to archaeological discoveries.

You can claim one of these for yourself to support the all-volunteer and labor-of-love BelleIsle Hall Acadian Cultural Center.

Additionally, Charlie and Jennifer Thibodeau, who established the Center, commissioned an amazing drone video as a fundraiser.

Ron, another Acadian cousin with a keen historical interest took the results of the drone video and overlaid the Savoie/LeJeune village print onto the land where the archaeology excavations revealed homestead remains and a well.

Courtesy of both the Center, with the Acadian roof, located on Savoie land, and Ron who merged the two, feast your eyes upon this beauty.

This depicts the original Savoie homestead where Catherine would have been tending her garden, milking the cows and baking in the Acadian oven. It’s here that she had her babies and raised her family.

It’s also probably here that Catherine and her sister grew up, with Catherine marrying the neighbor boy.

Life was peaceful, beautiful, and bucolic along the river, a dream come true, right up until it wasn’t.

1654

In Acadia, life unexpectedly changed in 1654.

Catherine LeJeune, 20 or 21, hadn’t been married very long – maybe three years. She had one baby, Francoise, born around 1652, and was pregnant for her second child, Germain, who was born sometime in 1654.

She was either pregnant when the English launched a surprise attack upon Acadia, or she had a newborn baby, plus a toddler who was maybe two. I’m not sure which scenario would have been worse. God-forbid that she was acually giving birth during the attack.

Port Royal and the Annapolis River Valley for a few miles upriver had roughly 270 people in 1754, which consisted of maybe 40 families, assuming each family had approximately seven members. Acadians were living at Port Royal near the fort and also scattered up and down both sides of the river.

We also don’t know for sure if Catherine and Francois were living in Port Royal, along with many of the original families, or if they were living upriver, at BelleIsle, clearing the marshes as originally ordered by d’Aulnay, between 1636 and his death in 1650.

I’d wager that they were at BelleIsle and had been all along, but we will never be positive.

If they were living at BelleIsle, they would have been safer than in Port Royal, even though Port Royal was protected by Fort Anne.

The English were familiar with the fort and the layout of Port Royal, but they would never be able to navigate the mountains behind BelleIsle.

The Acadians, on the other hand, certainly would have been familiar with the woodlands behind their homes. The women and children may have sought safety there.

The English attack on Port Royal wasn’t planned in advance – it was rather spontaneous.

Nicolas Denys reported that Robert Sedgewick of Boston had been ordered by Oliver Cromwell to attack New Holland (New York). As Sedgewick prepared, a peace treaty was signed between the English and the Dutch.

Sedgewick commanded 200 of Cromwell’s professional soldiers, plus 100 New England volunteers and found himself in a snit.

Since Sedgewick was “all dressed up with nowhere to go,” he attacked various locations in Acadia in August 1654 and destroyed most of the settlements, even though it was peacetime. This included Castine in Maine, Port Royal, La Hève, and at the Saint John River.

Sedgewick sailed up the Riviere Dauphin to Port Royal in July 1654, facing about 130 Acadian men and soldiers who valiantly attempted to defend the fort. Not only were the brave Acadians outnumbered, more than two to one, but the 200 English soldiers were professionals.

The Acadians did their best and holed up in the fort, but the English held them and Port Royal under siege.

On August 16th, the Acadians surrendered to the English, having negotiated what they felt were reasonable surrender terms. The French settlers were to keep their land and belongings, the French soldiers in the fort were to be paid in pelts and transported back to France, not killed, and the Acadians could worship as they saw fit – meaning as Catholics. The French officials would also be sent back to France, and an Acadian council was put in place to function on behalf of the English during their absences. Acadian Guillaume Trahan was in charge.

Those terms could have been much worse since both the English and the French knew very well that the Acadians stood no prayer of winning against the English who both outnumbered them and were far more experienced.

Brenda Dunn, in her book, A History of Port-Royal-Annapolis-Royal, 1605-1800, reports that in violation of the negotiated terms of surrender, the English soldiers rampaged wildly through the town afterwards, including through the monastery and newly constructed church, smashing windows, doors, paneling, and even the floor before torching it all. This is par for the course, and we know they did this multiple other times.

Sedgewick then departed from what was left of Port Royal.

It was later reported that only 34 families chose to remain in Acadia after the 1654 attack. Settlers also had the option to return to France on the ships with the soldiers and officials.

The Acadians who stayed were allowed to retain their lands, goods, livestock, and to continue worshiping as Catholics. However, if your home had been burned, this turn of events could have provided motivation to return to France, to move upriver if you had been living in Port Royal, or to perhaps move a little further upriver. I doubt any Acadian wanted to reside near the English-controlled garrison that had been the Acadian fort, nor in close proximity to the English who would have established themselves in the town, which was the seat of the English governance of Acadia for the next 16 years.

If, in fact, the Catholic church was destroyed, which is quite likely, based on every other time the English took Port Royal, the chapel at St. Laurent at BelleIsle was probably built and came into use about this time.

Church services would have been held in Acadian homes or the St. Laurent Chapel, or both. The devoutly Catholic Acadian people weren’t going to let the little issue of a church building stand between them and their much-loved and comforting religious rituals and their relationship with God.

We don’t know a lot about Acadia during the years before the French regained control in 1667 through the Treaty of Breda. No new French settlers arrived during the years under English domination. In 1668, France physically took possession of Acadia again, although that was contested until 1670 when the new French Governor arrived with 30 soldiers and 60 new settlers. His headquarters, though, was at Fort Pentagouet, the Capital of Acadia, in today’s Castine, Maine, until that Fort’s destruction by the Dutch in 1674.

Thankfully, one of the first things the Governor Grandfontaine did was to order a census to be taken by Father Laurent Molin, a humble Cordelier and parish priest at Port Royal, in the spring of 1671. Ironically, there is no census of Fort Pentagouet.

It’s through the 1671 census that we obtain a glimpse of Catherine’s life between her marriage around 1651, 1654 when Acadia fell into English hands, and 1670 when Port Royal became French again.

The 1671 Census

In the 1671 census, Catherine LeJeune, was married to Francois Savoie, who was born about 1621.

Based on their children’s ages, Catherine and Francois had been married by 1651 or 1652, assuming that their oldest children had not died.

Their family consisted of:

- Francois Scavois (Savoie), farmer, age 50 (so born about 1621), with 4 cattle, cultivating 6 arpents of land

- Catherine LeJeune, his wife, age 38 (so born about 1633)

Children:

- One married daughter, Francoise, 18, is listed next door with her husband Jehan Corporon, farmer, age 25, and a six-week-old daughter not yet named. Additionally, they are listed with “cattle, 1, sheep, 1, and no cultivated land”.

Francois and Catherine’s unmarried children are:

- Germain, 16

- Marie, 14

- Jeanne, 13

- Catherine, 9

- Francois, 8

- Barnabe, 6

- Andree, 4

- Marie, 1 and a half

We can’t tell for sure where they lived, but they are found among other families who, at least eventually, lived on the north side of the river, at or near BelleIsle, including the Dupuis, Blanchard, Terriau, Martin, Brun, and Trahan families.

We also know that Francois is farming 6 arpents of land and has livestock, so living on the main street along the water in Port Royal is very unlikely.

We know that some of these families listed on the census; Martin, Blanchard, Trahan and Gautrot, were early families to settle at Port Royal, because they are among the families with land expropriated in 1703-1705.

A Buried Hint

I think there’s a subtle hint buried in the census.

Catherine’s daughter, Francoise, lives in the adjacent house, and they have no property. This tells us that they are living on the land of Francois Savoie and Catherine LeJeune, probably just feet away, sharing both the communal well and farm chores.

Think about the structure of the Savoie village at BelleIsle.

Francoise and her husband, Jean Corporon, have a daughter that is six weeks old and not yet named. If the baby isn’t named, that also means she’s not baptized, because Catholic children are named at baptism.

If the family was living in Port Royal, which is where the Catholic priest, Father Molin, would have been living, then the baby would assuredly have been baptized within days, if not hours, after birth.

The priest probably didn’t travel upriver often, especially not in the winter when the river was dangerous. If the census was taken in the spring, then the baby would have probably been born in mid to late winter, early 1671.

The fact that the child is not yet baptized suggests VERY STRONGLY that the family is NOT living at Port Royal, and is living at BelleIsle where their family members are found in the future.

There’s something else rather unusual about Francoise Savoie and Jean Corporon that may tie in to the child not yet being baptized. I realize this is heresy, but they might not have been as religious as other Acadians.

Why didn’t they just have the priest baptize the baby when he was there to take the census, then the baby wouldn’t have had to be recorded as unbaptized? The priest was literally standing right there – unless he created the census from memory. But he couldn’t have done that if he had not visited over the winter because both births and deaths would have occurred – including this baby.

Eventually, Francoise’s daughter, Isabelle, had a “natural child,” meaning without being married, about 1707, and daughter Marguerite had four illegitimate children between 1709 and 1715. Marguerite eventually did marry the presumed father of the youngest child a decade later. The Catholic church, plus community sentiment and pressure, served to prevent almost all out-of-wedlock conceptions.

For some reason, this family didn’t exactly fit the mold. Not only that, but Catherine and Francois came and went in the census, as did several of their children – like Acadian fireflies. That too was very uncommon, especially as a pattern.

The next census, 1678, is a mystery on several levels.

Mystery – Missing in 1678

By 1678, Catherine LeJeune and married daughter, Francoise Savoie, along with most of Catherine’s family, are no longer listed in the census, but three of her children are. Germain, Jeanne, and Catherine Savoie have married and are listed in the census with their spouses and young families.

Where is everyone else?

It’s unclear if Catherine LeJeune and Francois Savoie have died, or if they are simply missing from the census. This situation doesn’t necessarily make sense, but here it is, nonetheless.

- In 1678, Catherine’s eldest daughter Francoise Savoie and husband Jean Corporon, who were present in 1671, aren’t listed either, but they are in 1686.

- Daughter, Marie Savoie, based on the 1686 census, had given birth to a child in 1677 and 1679, so clearly would have been married well before 1678, but neither Marie nor her husband are shown in the 1678 census.

- Sons Francois Savoie and Barnabe Savoie are never found again after 1671, so it’s probably safe to say they died sometime between 1671 and 1686. They may have died before 1678, but since the rest of the family is missing, we don’t know.

- Daughter Andree Savoie married about 1683, but she is not found anyplace living with a family in 1678 either.

- Marie Savoie, the baby in 1671, was missing in both 1678 and 1686, but married Gabriel Chiasson around 1688 according to the 1693 census, when they are living in Minas.

Catherine LeJeune was only 38 years old in 1671, and her youngest child was a year and a half old.

Catherine was probably already pregnant with the next child, who would have been born shortly – except there is no evidence of another child being born.

Catherine could potentially have had at least one more and possibly two additional children, in maybe 1672/73 and 1673/74, but there is no evidence that Catherine had any more children.

This suggests two possibilities.

- Either Catherine died in or shortly after 1671

- Or, Catherine had more children, and Catherine plus the children born in or after 1671 all died before either 1678 or 1686 when other family members are present

There is a document that suggests that sometime either in or before 1679 that land was granted at BelleIsle to Francois Savoie, but by 1686, he’s gone too.

Where were they?

It’s unlikely that they left, because their minor children appear as married adults in Port Royal in subsequent censuses and/or in church records. Their children would have married where they lived.

If Catherine died, and she assuredly had by 1686, someone had obviously taken her orphan children to raise. Perhaps their oldest sister, Francoise, but why don’t those children appear anyplace in the census? I don’t see other orphans in the census either, and the Savoie children can’t be the only orphans in Acadia.

Catherine’s Children

Speaking of Catherine’s children, there’s probably more to that story as well:

By 1671, there’s a conspicuous gap between Jeanne and Catherine where a child should have been born about 1660.

This tells us that Catherine lost her parents, plus one child in about 1660, plus her sister, Edmee, lost children in roughly 1647, 1650, 1656, 1663, and about 1667.

Both Edmee and her husband were living in 1686, but had died by the 1693 census.

Those small bodies were probably buried in what is now called the Garrison Graveyard in Port Royal, adjacent the fort.

At the time, it was a small Catholic cemetery, standing in a small fence behind the Catholic Church as shown in this 1686 map.

Catherine probably walked through this cemetery, speaking quietly to her parents, and stood with her sister as both of them said final goodbyes to their young children.

There’s nothing as “alone” as a mother burying her child.

We do know that there was another chapel, St. Laurent, at BelleIsle, and we know it was active by 1702 in the earliest extant records. It’s likely that St. Laurent began to be used at least by 1690 when the English overran Port Royal and took the fort, and possibly as early as 1654 when the earlier English incursion occurred. Nothing remains of St. Laurent today, except a grassy field.

Of course, Catherine was gone before 1690, perhaps buried at St. Laurent or here at Port Royal.

Catherine’s Children and Grandchildren

Catherine’s oldest child, Francoise, already had a daughter by the time Catherine died. Catherine may have had other grandchildren before her death too, but we have no way of knowing. One thing is certain – Catherine’s younger children grew up without their mother.

What happened to her children? Where did they live? Did they have children of their own?

It’s easiest to visualize the family in a chart. The Acadian censuses that extended from 1671 through 1714 paint a picture of family development – marriage, birth, and death. Some of Catherine’s family was missing in various censuses, too.

| Child |

Spouse – Marriage |

Census |

Children |

| Francoise Savoie born circa 1652 died Dec. 27, 1711, Port Royal |

Jean Corporon married circa 1670 d 1713 |

Married circa 1670, 1671, missing 1678, 1686, 1693, 1698, 1700, missing in 1701 & 1703, 1707 |

15, 3 died young, 1 died on Ile St. Jean circa 1756, the rest died before 1755, 3 at Port Royal, 3 in Pisiguit, 2 in Louisbourg, and 1 in Grand Pre, the fate of 1 is unknown |

| Germain Savoie born circa 1654, died before Oct 1749 |

Marie Breau married circa 1678 d 1749 |

1671, married in 1678, 1678, 1686, 1693, 1698, 1700, 1701, 1703, 1707, 1714 |

12, 5 spaces for deaths, 3 died young, 1 died at Port Royal 1 died in Duxbury, MA, 1 widowed in 1711 but died in Quebec in 1770, 1 in Quebec, 1 in New Rochelle, NY, 1 in South Carolina, 1 probably at Camp d’Esperance in winter of 1756/57, the fate of 2 are unknown |

| Space for Child born circa 1656, died before 1671 |

|

|

|

| Marie Savoie born circa 1657 died March 1741, Louisbourg |

Jacques Triel married circa 1676, died before 1700 |

1671, married in 1676, missing in 1678, 1686, 1693, 1698, 1700, 1703, missing in 1707 & 1714, in Louisbourg by 1724 |

5, last child born in 1690, at least 3 died earlier, and probably 5 more before 1700, 2 died as teens, 1 as young adult, 1 in Louisbourg, and 1 on Isle Royal in Lake Superior |

| Jeanne Savoie born circa 1658 died Nov 1735, Port Royal |

Etienne Pellerin married circa 1675 d 1722 |

1671, married in 1675, 1678, 1686, 1693. 1698, 1700, 1701, 1703, 1707, missing 1714 |

10, spaces for 3 deaths, 1 died as a teen, 1 died in Port Royal, 1 in New London, CT, 1 in Quebec, possibly of smallpox, 1 in Chezzetcook after expulsion, fate of 5 unknown |

| Space for child born circa 1660, died before 1671 |

|

|

|

| Catherine Savoie born circa 1662 died Januart 1725, Port Royal |

Francois Levron married circa 1676 died 1714 |

Married circa 1676, 1678 living with Widow Pesselet, 1693, 1698, 1700, missing in 1701, 1707, 1714 |

10, space for 6 deaths, 3 died at Port Royal, 1 died in Medfield, MA, 1 was probably at Camp d’Esperance winter of 1756/57, 1 Pisiquit, 1 at Louisbourg, 1 at or near Fort Frontenac, 1 at Grand Pre, fate of 1 unknown |

| Francois Savoie born circa 1663 died before 1686 |

|

Missing 1678 and thereafter |

Died between age 8 and 23 |

| Barnabe Savoie born circa 1665 died before 1686 |

|

Missing 1678 and thereafter |

Died between age 6 and 21 |

| Andree Savoie born circa 1667 died after 1714, probably Port Royal |

Jean Prejean married circa 1683 d 1733 |

Missing 1678, but alive, married in 1683, 1686, 1693, 1698, 1700, 1701, 1703, 1714 |

12, spaces for 5 deaths, 1 probably died in Bristol, England in 1755/56, 1 at Camp d’Esperance in winter of 1756/57, 1 at Chipoudy and probably at Camp d’Esperance, 1 in 1765 in Landivisiau, near Morlaix, France, 1 possibly in NY before 1763, 1 in Quebec, 1 at sea with entire family of 11, fate of 5 unknown |

| Space for child born circa 1669, died before 1671 |

|

|

|

| Marie Savoie born circa 1670 died between 1711 and 1714 in Beaubassin |

Gabriel Chiasson married circa 1688 died 1741 Beaubassin |

Missing in 1678 and 1686 but alive, married in 1688, 1693 |

11, space for 3 deaths, 3 children died young including her first two, 1 died in 1758 on Ile St. Jean, 1 died at sea in 1759 with husband on way to France during expulsion, 1 in 1759 in St. Malo after arrival in France, along with son 4 days later – wife had died at sea, 1 in SC, 1 in 1759/69 in St. Malo, 1 uncertain, 1 in Quebec, youngest died in 1758 on board the Violet with 4 children when the ship sank en route to France during forced expulsion |

| Space for child born circa 1671, no record |

|

|

|

| Space for possible child born circa 1673 |

|

|

|

Several children are inferred due to spaces that are “too long” between known children. These are the whispered children – those no one talks about because it makes the mother cry.

We do have the names of two sons, Francois and Barnabe who died relatively young, probably as children, but not at birth.

Francois Savoie was 8 years old in the 1671 census, and his little brother Barnabe Savoie was 6. They never appear in any other records of any type, so they assuredly died before adulthood. They don’t appear in any future census, either as children or adults, nor do they have any children in church records, nor is their death recorded in or after 1702 when the existing Port Royal records begin. They aren’t found anyplace else either.

In case you are wondering, yes, Catherine really did have two children named Marie Savoie, and no, I don’t know why. They both lived, so the second Marie wasn’t named in honor of the first one. My guess would be that both had a middle name, but it’s odd that neither are recorded in the census or other records by that name, so I simply don’t know. I would think it would be very confusing for everyone involved, but it’s certainly not unheard of.

Catherine’s youngest two children who were missing in 1678, Andree Savoie and Marie Savoie, and Marie, who is also missing in 1686, were living someplace, with someone, in the Port Royal area because they married there and are found living there later.

The older daughter, Marie, found her way to Louisbourg and died there sometime after she was widowed in 1700 and before 1724.

Only the youngest daughter, Marie Savoie, made her way to the northern settlements shortly after her marriage.

Catherine’s youngest children could potentially have lived long enough to witness and be unwilling participants in the horrific 1755 Expulsion, but they did not.

Catherine’s grandchildren, however, were another matter, and many were ensnared in the Grand Dérangement, also called the expulsion, exile or deportation. By whatever name, it was a horrific, genocidal unfolding tragedy that began in 1755. No Acadian was untouched, and the trajectory of their lives was forever altered, or ended.

Catherine’s Grandchildren

Catherine had 75 known grandchildren. She assuredly had more, but records were spotty and I am only including the people who can be positively associated with Catherine’s children. I’m not counting the “vacant spaces,” of children who died. There are about 30, and I wish we could preserve their memory by saying their names. 30 is a lot, and I’m sure that’s low given that we lose track of some people.

- We know that 13 of Catherine’s grandchildren died young. Given that Catherine died before 1686, she would have missed most of that pain. But she would also have missed the joy of births, baptisms, and birthdays.

- Three more children died as either late teens or young adults in Port Royal.

- Five died as adults in Port Royal.

- Eight of Catherine’s grandchildren died after childhood elsewhere in Acadia before the expulsion began.

- Twenty-nine of her grandchildren died during or after the expulsion. In other words, they did not die before that horror unfolded, and we know something about them at the time of deportation or even just a glimpse where they surfaced after.

- Seventeen of her grandchildren simply disappear from the records, most shortly prior to or during the deportation. Many of these people perished at the hands of the English on those horrid ships.

- Of those who survived the expulsion, few wound up in the same place, so they were ripped from their families, never knowing their fate. “Survived” is a relative term.

The only grandchild Catherine would have known, that we know of for sure, is that sweet little six-week-old baby that was unnamed in the 1671 census. That baby was eventually named Marie and went on to marry around 1687, eventually having a child she named after her grandmother, Catherine. I wonder if Marie remembered her grandmother.

Of course, depending on when our Catherine LeJeune died, there may have been a few more grandchildren that she was able to welcome into the world. Maybe she helped deliver them, witnessing their first cry. Maybe some were born silent, and never cried. Maybe she comforted her children as they stood in the cemetery together.

In total, 24 of her grandchildren were born before 1686, when we know Catherine was gone.

While these are the very abbreviated snippets of Catherine’s grandchildren, their stories and the Acadian history are fairly universal for all Acadians in Nova Scotia, both pre-and post deportation.

Since Catherine never got to meet most of her grandchildren, and certainly never knew what happened to them after her death sometime between 1671 and 1686, let’s introduce them.

Catherine, Meet Your Grandchildren!!

Catherine, since you never had the opportunity to meet most of your grandchildren, let me introduce you! By the way, you’re my 8 times great-grandmother, so pleased to meet you.

Let’s start with your daughter Francoise’s children. I know you got to hold her firstborn child, rocking her by the fireplace the winter she was born! I bet you were pregnant yourself at the time, expecting your next baby.

Since you couldn’t be there to witness your grandchildren’s lives, I’ve traveled in time to locate them and introduce you to their lives. They lived in very “interesting” times, and we have pictures, memories we can look at, today.

I visited many last year, some that I wasn’t even aware of at the time. Somehow, Catherine, I think your spirit might have been involved, and I know you walked with me.

- Francoise Savoie, Catherine’s eldest child, who married Jean Corporon, had six children before 1678, and nine before 1686 according to the 1671 and 1686 censuses. Catherine might have known at least some of them. Of Francoise’s 15 children, 5 died young, and of those who survived, 9 died in Acadia before the expulsion.

Catherine’s first granddaughter, who was eventually named Marie Corporon, died sometime after 1714 when she was 42, probably in Pisiquid. It’s possible that she survived and was embroiled in the horrendous deportations in 1755, but unlikely given that she would have been about 84 by then.

Cecile Corporon, age 37 died about 1721, and Martin Corporon, about 62, died in 1749, also in beautiful Pisiguit, with its own tidal river that would remind you of your own Rivière du Dauphin in Port Royal.

A second daughter, also named Marie Corporon died young, around 8 years old, after 1686, in Port Royal.

Francois Corporon died between the ages of 9 and 11 in Port Royal, between 1698 and 1700.

Charles Corporon died between the ages of 2 and 7, between 1693 and 1698 in Port Royal.

Ambrose Corporon died between the ages of 2 and 4 between 1698 and 1700 in Port Royal.

Marie-Madeleine Corporon, about 41, died in 1735 in Louisbourg and son Jean Corporon, born about 1677, so about 64, died there in 1741. Francoise Savoie had two sons named Jean.

Jacques Corporon died at about age 25, probably in Port Royal. He is not found in any records after 1700.

Madeleine Corporon, about 81, died about 1753 in Grand Pre. This beautiful tree, located in what was the village outside the church may have been standing when she lived.

Son, Jean Corporon, born around 1692, was caught up in the expulsion when he was about 64, and spent the horrific winter of 1756/1757 at Camp d’Esperance. Some refugees escaped into the woods from there, some were later deported, but many died. Nothing more is known about his fate or that of any family, although Stephen White states that he died in September of 1656 at Port LaJoye.

Marguerite Corporon, born about 1685, was the family wild-child or free spirit. She had four illegitimate children between 1709 and about 1715, and married the presumed father of the youngest child, an Englishman, a decade later in 1725. We don’t know Marguerite’s fate, but I surely would love to know more about her and her life.

Isabelle Corporon died at about age 44 in Port Royal, and Jeanne Corporon died at about 62 in 1735 in the same location.

- Son Germain Savoie who married Marie Breau, another BelleIsle family, about 1678, had 3 children before 1686, so Catherine may have known some of them.

Marie Savoie died at around 6 years old between 1700 and 1701 in Port Royal.

Pierre Savoie died at age 20 in 1710 and is buried at St. Laurent at BelleIsle.

Marguerite Savoie died at the age of 20 months in January 1711 and is buried at St. Laurent at BelleIsle.

Claude Savoie died at about age 20 in 1728 in Port Royal.

Germain’s son, Germain Savoie, disappears from the records after 1749 in Port Royal when he is about 67. He may have been exiled.

Francois Savoie is in Restigouche, where he disappears from the record after his youngest son’s birth in 1734 when he is about 50, but his children fled to Camp d’Esperance during the expulsion.

Marie Savoie was deported to South Carolina in 1755. Many Acadian refugees who arrived there were processed through the “pest house” on Sullivan’s Island, outside Charleston, suggesting they had diseases or were ill.

She was listed in SC on the 1763 census when she was about 24, as a widow, with her son. We don’t know what happened to her or her child after that.

Another daughter, also named Marie Savoie died at 95 in Duxbury, Massachusetts in 1767. Duxbury is generally thought of more in the context of the Pilgrims, but the Acadians and Pilgrims were contemporaries of a sort. By the time Marie Savoy lived here, or Marie Savory as she was buried in 1767, the John Alden house, built about 1700, was already 50-60 years old. Marie assuredly would have seen this home and was probably inside it, even if it might have been in the capacity of a servant.

Ironically, the only cemetery that seems to have been in operation at the time in Duxbury was the Standish Cemetery, which is probably where the Acadian unmarked burials lie. The graveyard was beside the original meeting house, and I have to wonder if our displaced Catholic Acadians attended church, even if it wasn’t their own version of Christianity, because the church of opportunity was better than no church at all.

Jean Savoie was in Chipoudy in 1755 when he was about 64, so probably at Camp d’Esperance in 1756/1757, although there was fierce resistance at Chipoudy. We don’t know what happened to Jean. Chipoudy is now Shepody, New Brunswick.

Paul Savoie removed to Chipoudy in the 1720s but his fate after 1745 when he is 49 is also unknown.

Marie-Magdelaine Savoie lived in Port Royal before the expulsion and died at the Hotel (Hospital) Dieu De Quebec in Quebec City in 1770 at age 76. It’s unknown where she was after the deportation, and before making her way to Quebec.

Charles Savoie and his family left Port Royal on the ship, Experiment, and were exiled to New York in 1755. The trip should have taken about 28 days, arriving in early or mid-January. However, the Experiment encountered a dreadful storm, was blown off course, and ended up in Antigua until May of 1756, when it finally sailed for New York.

After arrival, when Charles was about 56, the family was sent to New Rochelle on the Long Island Sound. At least 30% of the passengers had died during the months-long ordeal.

Marie-Josephe Savoie lived in Beaubassin, seen here in the distance, and died at about 51 in 1757 in Quebec City.

- Marie Savoie who married Jacques Triel about 1676 had 4 children before 1686, so Catherine may have known them.

Marie’s son, Pierre Triel was living on Isle a Descoust on the Isle Royale in 1752, which is in Lake Superior. The Isle a Descoust history tells us that: “The Isle a Descoust is a land area that was chosen for settlement by Monsieur Triel, and was situated on the Isle Royale. Isle Royale, a park in the U.S., is a remote location in Lake Superior, reachable by ferry, private boat, or seaplane. The park is known for its wilderness, with over 99% of the land designated as such.”

Pierre was one hearty man, especially at age 75, given that there are no full-time residents today due to the harsh winter conditions. I have so many questions about this!

Marie-Madelaine Triel died in Louisbourg in 1733 at about age 54. There were several smallpox deaths that year.

Nicolas Triel and Alexis Triel died as late teens or young adults, and Marie Triel died at age 21 in Port Royal after marrying, leaving one child.

- Jeanne Savoie who married Etienne (Estienne) Pellerin about 1675 had two children before 1678 and 5 before 1686. Catherine may have known some of them.

Of Jeanne’s 10 children, one died young, some died in Acadia, and some were caught up in the expulsion.

Pierre Pellerin died after the 1701 census in Port Royal where he is 19.

Madeleine Pellerin married twice, but disappeared after the 1707 census in Port Royal when she was about 41.

Marguerite Pellerin died at about 24 in 1724 in Port Royal, just 8 days after giving birth to a child who survived.

Marie Pellerin disappeared in the records after 1751 when she was about 73, Bernard Pellerin after 1730 when he was about 39, and Jean-Baptiste Pellerin disappeared after 1749 when he was about 64, all in Port Royal, so they may have disappeared during the expulsion.

Anne Pellerin is believed to have been exiled to Connecticut where the ship arrived in January 1756 in the New London harbour. Anne lived with her son and may have died about 1789 in New London at the advanced age of 103.

Jeanne Pellerin died in 1758 in Quebec City and was buried at Notre Dame De Quebec Basilica-Cathedral, but there’s far more to her story. Jeanne was a 67-year-old widow, when, according to Stephen White, she was swept up into an act of resistance:

On 8 December 1755, Jeanne Pellerin, widow of Pierre Surette, and 3 of their daughters were very likely among the people who left Port-Royal aboard the Pembroke, destined for exile in North Carolina. The Acadians on board seized the ship and headed towards the St-John River in New Brunswick. They later moved upriver to Ste-Anne-du-Pays-Bas where they settled for the winter. Afterwards, Jeanne Pellerin and her daughters sought refuge in the city of Québec where Jeanne died during the smallpox epidemic that had developed between November 1757 and February 1758.

Charles Pellerin’s youngest child was born when he was about 56, in 1746 in Port Royal. We don’t find Charles in records thereafter, but all of his children wind up in Quebec and are buried where his sister, Jeanne, is interred. I wonder if they were on the same ship. If Charles survived the deportation, he is most likely there too, but there are no records for him. His wife died in Quebec in 1789 and was buried in the cemetery for Smallpox victims.

Alexandre Pellerin died in Chezzetcook, Nova Scotia in April of 1770, a location where Acadians who eventually returned could provide newly-formed Halifax with lumber and other supplies. Of course, their land had been redistributed, so there was no “returning” to the homes or even the locations they had left.

- Catherine Savoie who married Francois Levron about 1676 had 4 children before 1686. Perhaps her mother, Catherine LeJeune was able to attend her 1676 wedding and was there to welcome at least some of her grandchildren.

Pierre Levron died in January 1725 in Port Royal at about the age of 30, unmarried and working as a domestic for Pierre Godet – a very unusual situation.

Madeleine Levron died at about age 80 in 1752 in Pisiquid.

Marie Levron died in 1727 in Port Royal.

Anne Levron died in 1733 in Louisbourg.

Elizabeth Levron was found on the 1757 census at Medfield, Massachusetts, about 17 miles outside of Boston, and died after August of 1763 when she was about 73. The Vine Lake Cemetery is the old town burying ground, and is where Elizabeth is assuredly buried in an unmarked grave.

Joseph Levron married when he was about 59 in January 1750 in or near Fort Frontenac, Pays d’en Haut, Nouvelle-France, a fur-trading outpost on the St. Lawrence River. Today, the location is Kingston, upriver from Montreal at the mouth of Lake Ontario. We don’t know much about him after that, except that the expulsion did not affect him.

Jean Baptiste Levron was living in Grand Pre by 1737 where his youngest child was born in 1741. Jean-Baptiste was about 49. In March 1756 when his son married at Port LaJoie, Prince Edward Island, Jean Baptiste is noted as deceased.

Jacques Levron died sometime after his youngest child’s birth in 1736, when he was 59, but before February 1746, probably in Port Royal, but we don’t have his death record.

Jeanne Levron, a 57-year-old widow, died in January of 1751 in Port Royal.

Madeleine Levron, born about 1700, was in Chipoudy in 1752 and 1755, so was likely at Camp d’Esperance during the winter of 1756/1757. Nothing more is known.

- Andree Savoie who married Jean Prejean in about 1683 had one child before 1686 that Catherine might have been able to welcome into the world.

Of Andree’s 12 children, other than children who are only represented by spaces between other children, none are known to have died and been buried at Port Royal, although her eldest child, Marie, may be.

Marie Prejean died sometime between November 1753, where she is last mentioned in Port Royal, and November 1758 when her daughter remarried in Quebec and she is noted as deceased. Marie was about 49 in 1753. She was probably lost in the expulsion.

Anne Prejean was married to Michel Boudrot and living in Grand Pre when the men were rounded up in the St. Charles des Mines church.

On 27 October 1755, Michel (about age 70) and Anne (about age 68) were deported to Virginia, but the colony was not accepting Acadians who were considered a financial burden. The governor of Virginia refused to accept ships full of foreign, impoverished prisoners, which is what they were considered.

After allowing the refugees to winter over in port, they were deported again in May 1756 to England, aboard the Virginia Packet carrying 289 Acadians.

They disembarked in Bristol, England in June of 1756 where they were neglected and subjected to poor conditions, causing many deaths from smallpox as a result. They both died between September 1755 and the Smallpox epidemic at the end of September 1756 in Bristol, England. If she was not buried at sea, she was likely buried in a mass grave for Smallpox victims.

Pierre Prejean disappears in the records after 1749 when his wife died in Port Royal. He was about 59.

Jean-Baptiste Prejean was at Chipoudy at 1752 and recorded at Camp d’Esperance in the winter of 1756/1757 when he was about 64, but nothing is known of him after except that he is dead by June 1760 when his daughter married in Ristigouche, New Brunswick.

Francois Prejean married at Port Toulouse on Isle Royal in 1722, Cape Breton Island, when he is about 27, and had several children. He is not well-researched, is also reported on Prince Edward Island, and disappears from the records.

Madeleine Prejean is found in her daughter’s marriage record in 1752 in Port Royal, when she is about 55, but there is no record thereafter. Two of her married daughters were sent to Maryland and Connecticut, respectively, but neither Madeleine nor her husband, Charles Doucet are found.

Joseph Christome Prejean was at Chipoudy in 1755 when he is about 55, so his family was probably at Camp d’Esperance in 1756/1757. Stephen White claims that he died in August of 1756.

Marie Josephe Prejean married Joseph Mius and they had returned to his home region of Pobomcoup by 1735. She was alive in 1747 when her daughter was born, but we don’t know much after that, at least until her husband remarried in Philadelphia on October 10, 1760, after being exiled. She died between the ages of 45 and 58, either in Acadia or possibly Pennsylvania.

Nicolas Prejean was in Port-Toulouse in 1752, and was deported in 1758 on the ship, Queen of Spain, arriving at St. Malo on November 17, 1758.

He lived in St. Malo for some time, remarrying there in January of 1760 in Saint-Servan. I’m not sure if the marriage record refers to the church by that name in Saint Malo, or the village just outside of, and now a part of, St. Malo.

Nicolas Prejean is reported to have died at about age 61 in 1765 in Landivisiau, near Morlaix, Finistere, France, although I surely wonder at the back story because this is more than 175 km from St. Malo, and no place that the Acadians settled.

Charles Prejean was in Port Royal in 1743 when his youngest child was born and probably in 1752 when his eldest was married. The family was exiled to New York 1755, when he was 49, where his widow was found with their 5 children in August of 1763. We don’t know if he died before, during or after the expulsion. However, his widow, Marguerite may have been exiled to Philadelphia by the British in 1756, although she is not on the list. However, she journeyed to the West Indies and settled in Port-au-Prince where she lost three of her sons shortly after their arrival and did not survive long thereafter.

Pierre Prejean died in 1768 at about age 60 and was buried at Notre-Dame-de-Québec.

Today, the remains of the early burials at Notre Dame are held together in the Ossuary.

Honore Prejean and his family was recorded at La Briquerie, on Ile Royale (now Cape Breton) in 1752, listed with his wife and children, including a set of two and a half month old twins, not yet named. He had arrived in 1732, according to the census. The family of twelve was deported in 1758, when he was about 47, aboard the Queen of Spain.

Honoré, his wife, and all ten children died at sea during the crossing to France.

The Roll of the Queen of Spain, which disembarked at Saint-Malo on November 17, 1758, a list created by Louis-Xavier Perez, documents that of the 105 passengers, 66 died at sea and another 9 died shortly after docking. Only 28 survived.

Pregeant, Honoré, died at sea

Brossard, Marie, wife, died at sea

Pregeant, Félicité, daughter, died at sea

Pregeant, Paul, son, died at sea

Pregeant, Madeleine, daughter, died at sea

Pregeant, Cyprien, son, died at sea

Pregeant, Pierre, son, died at sea

Pregeant, Marie Anne, daughter, died at sea

Pregeant, Julien, daughter, died at sea

Pregeant, Félix, son, died at sea

Pregeant, Marguerite, daughter, died at sea

There just aren’t enough crosses for this.

- Marie Savoie who married Gabriel Chiasson about 1688 was living in Minas by 1693 with her husband and two children.

Of Marie’s 11 children, three died young, including her first two children, Michel and Pierre.

Michel Chiasson died when he was about 11 at Minas, a group of Acadian settlements in the Minas Basin.

Pierre Chiasson died when he was between 2 and 8 in Minas.

Another son, also named Pierre, died in 1712 when he was about 11 in Grand Pre.

Jean Baptiste Chiasson died in February 1758, about age 66, on Ile St. Jean, just a few months before the expulsion began from that location. He was one of the lucky ones.

Marie-Josephe Chiasson married in Beaubassin in 1715 and was living with her family on St. Pierre du Nord, Ile St. Jean, Acadia, to the east of the pond of Saint-Pierre, in the 1752 census. She, along with her husband Jacques Quimine and their children were forced aboard one of the infamous “Five English ships” which set sail for France. The ship arrived at Saint Malo on January 23, 1759. Marie, Jacques, and one married child had died during the crossing, in addition to several grandchildren.

Quimine Jacques, 60, died at sea

Chiasson Marie, his wife, died at sea

Quimine Françoise, 23, daughter

More family members died in the days and weeks after arrival.

Some of their children remained in France, some eventually left for Louisiana, and some for French Guiana.

Francois Chiasson was born in Beaubassin and was living with his family at Anse-aux-Sauvages, Isle-Saint-Jean in 1752 when he was about 55. They, too, were deported upon one of the five ships, arriving on January 23, 1759 in Saint Malo.

Francois’s wife died during the passage, but he survived, barely. Francois’s son died just four days after arrival, and Francois died just a few weeks later.

The old hospital, where the critically ill Acadians were taken, and its attached chapel were located just inside the city gates and were demolished long ago.

However, they stood when Francois arrived and would have been where Francois and his son would have been taken as they were carried off the ship and through the St. Thomas or Saint Vincent Gate and around the tower in the walled city.

The hospital stood between the towers, with the adjacent St. Thomas Chapel.

Once inside the city walls, the hospital was attached to the wall between the towers, with the chapel adjacent. That space is a parking lot today that also functions as a communal market.

Today, the Brasserie of the Hotel Chateaubriand stands where Saint-Thomas Chapel once did. The St. Thomas Gate tower can be seen at right, with the Brasserie straight ahead. It was here, as in exactly here, that Francois and his son were taken, and last rites provided for his son.

After passing from this mortal life, the child would have been taken to Saint Saveur, a few blocks away, to be buried, probably in what is this courtyard today.

Normally, about a 10-minute walk, Francois was probably too sick, with whatever the Acadians were dying of on that ship, to attend his son’s burial service.

A few weeks after his son died, Francois would make this final journey himself, hopefully laid to rest beside his child and the rest of his family members, but that wasn’t the end of the trauma and heartache.

Additionally, Francois’s daughter, Anne, and her family were deported as well, losing their youngest child on the ship, and the next youngest about three weeks after arrival.

Francois’s son, Guillaume, who had his 30th birthday on the death ship, died four months after arrival in Saint Malo.

Francois’s daughter, Francoise was on the death ship too. She had lost two of her three young children at sea, and the third just three weeks after arrival. She joined them in the cemetery shortly thereafter.

Francois’s son, Francois, 19, survived the deportation voyage, but disappears from the records thereafter.

Francois’s son, Georges, 17, survived, as did daughter, Angelique, and son, Paul, as children. I can’t even begin to imagine the grief suffered by these young people, not just for the deaths of their parents and siblings, but also for the destruction of their homes, homelands and other family and community members on those five English death ships. Who would have been left to raise them?

Oh, Catherine, the mortal remains of so many of your family members lie here.

There’s far more history in Saint Malo than one might imagine. It’s not a well-known Acadian location, and I had absolutely no idea of my connection here when I visited. It was just a beautiful French walled city. Not anymore.

I serendipitously stayed here in the Chateaubriand hotel, attached to the restaurant, part of the building where the chapel stood, during my 2024 visit. And no, I have no way of explaining this incredibly providential coincidence. I didn’t put any of these pieces together until after I came home.

Jim is peeking out of the window on our second-floor balcony room.

Jim was ill when we visited St. Malo and ventured out only to eat and do what was necessary. I didn’t feel great, but felt better than he did.

Here, I’ve arrived back with lunch for Jim. I had been walking on the same cobblestones they had trod.

We had a picnic in the room overlooking the courtyard so Jim could rest, having no idea that my family had been very ill in this exact same place 268 years ago.

We discovered that you can call doctors in France and they make “house calls,” or in this case “hotel calls”, but not quickly.

I’m still just aghast that we were literally where Catherine’s grandchildren were hospitalized and died, my first cousins 8 times removed (1C8R). If there was a cemetery adjacent to the chapel, they may have been buried here as well, but Saint Saveur is the only one mentioned today.

Maybe they were trying to get our attention since, after almost 270 years, they finally had a visitor. They weren’t lost after all, if we could just HEAR THEM!!

I hear them now, loud and clear.

Here, I’m standing across from the entrance between St. Thomas Gate and St. Vincent Gate, looking down the street at the white building that was at one point the Saint Thomas Chapel. The hospital either stood to my right, or maybe even where I’m standing.

The white and blue building straight ahead is the restaurant where the priest in the Saint Thomas Chapel would have given last rites to the people in the hospital and carried the children away to be buried. The hotel is the slightly shorted attached building of the same style to the left.

From a different perspective, the city wall and towers at left, with St. Thomas Gate on my immediate left and St. Vincent’s Gate in the distance. The defunct hospital would be where the cars are parked today. The Chateaubriand restaurant and hotel is the white building at right, which was the chapel.

According to FindaGrave, the Acadians who perished after arrival were buried in the now defunct Saint-Saveur de Saint-Malo/Hotel-Dieu Cemetery. FindaGrave shows 208 memorials and states:

Chapelle Saint-Sauveur de Saint-Malo was built on the site of the former chapel of the Hôtel-Dieu. It was built between 1738 and 1744. The Hôtel-Dieu was a medieval hospital, founded in 1253, which was rebuilt in 1674. The Hôtel-Dieu had been on the same spot for hundreds of years but was destroyed by bombs in World War II. Nothing remains of the Hôtel-Dieu or the cemetery today other than the church, which was burned down in 1944 and restored in 1974. The church is now a museum and is located within the ancient city walls, of the original part of the city.

This horrific rolling tragedy of compounded grief took a toll on the living, the survivors, as well as those who perished during the forced crossing of the “5 English ships.”

Let’s take a deep breath and get back to the rest of Catherine’s grandchildren.

Abraham Chiasson was living at Menoudie when his farm was burned in 1750.

He sought protection at Fort Beausejour, above, and is found in Aulac in both 1752 and 1755.

His family records are held in Fort Beausejour’s church record books.

In 1755 after the seizure of the isthmus of Chignecto by Monckton, Abraham is among the Acadian men lured to Fort Beauséjour and imprisoned. He was deported with his family to South Carolina.

The Acadians were forced aboard the Cornwallis on August 11th, but didn’t sail until October 13th, with 417 passengers, or maybe hostages is a better word. The ship arrived about 5 weeks later, mid-November, with only 207 survivors. We find no records for Abraham, and he is not in the August 1763 Acadian census in South Carolina, so he is assuredly deceased by then, but some of his children eventually made it to Louisiana and Quebec.

Francoise Chiasson was born in Beaubassin and lived on Ile St. Jean, now Prince Edward Island, before being herded onto one of the five English death ships.

Francoise and her family arrived in St. Malo on January 23, 1759, surviving a brutal winter crossing, but many of her children and grandchildren did not, perishing either during the crossing or soon after arrival.

They must have dug graves every day at Saint Servan, and the cemetery was very clearly quite large.

She died in St. Malo sometime after her arrival and before October 1769. She walked these cobblestones by the walled city’s St. Thomas Gate throughout the remainder of her life.

She may have worshipped at St. Vincent’s Cathedral or at Saint-Servan where her family members were buried. The two churches were only three or four blocks apart.

Anne-Marie Chiasson married at Beaubassin and lived at St-Pierre du Nord.

Details are very sketchy, but Anne-Marie was likely transported to France, arriving at St. Malo like the rest of her siblings that lived in the same location. One record shows her son in St. Malo and one record places her burial at L’Assomption in Canada. Records conflict, and she needs more research.

Marguerite Chiasson and her family had already removed to Quebec between 1734 and 1737, which saved them from the deportation.

Marguerite died in the village of Montmagny, Quebec, on the St. Lawrence River, in 1780. She would have worshiped at Saint-Thomas-de-la-Pointe-à-la-Caille and been buried in the adjacent cemetery.

Judith Chiasson was living at Havre La Fortune, now Fortune Bay, Isle St. Jean, Acadia in 1752.

Late in 1758, Judith and her family were deported from Ile Saint-Jean aboard the ship, Violet. She, along with her husband, Pierre Le Prieur and her four youngest children died on December 13, 1758 when the horribly overcrowded Violet sank in the icy Atlantic during the crossing to France.

I can’t even begin to imagine their terror. I pray it was quick and while they were sleeping.

God rest their souls.

Catherine, I’m sorry, but know that your grandchildren may have been dispersed, but they also seeded thousands of descendants across the world today.

Let’s look at where they landed, were planted and took root. Many thrived and Catherine, in the next four generations, you have more than 16,115 descendants.

Your children and grandchildren would have made you proud. They were tenacious and look at us now – all thanks to you back in Acadia!!

Seeds Across the World

Strap yourself in, because we’re going on a quick flight around the world of Catherine’s 75 grandchildren in the places where I could find them. This “should be” a complete list – but we know it’s not because in each generatoin, we lost track of some people. I tried to find at least one photo for each location.

Let’s start in Port Royal which is beautiful no matter where you are along the meandering river. .

Catherine’s grandchildren were scattered widely. The ones who remained at Port Royal, which was renamed Annapolis Royal in 1710, would have been buried at either the Garrison Cemetery in Port Royal, or at the Mass House, St. Laurent, at BelleIsle, much closer to where they lived.

At least 21 of Catherine’s grandchildren rest in a cemetrey at Port Royal or along the river.

At least three of Catherine’s grandchildren are buried at St. Laurent, or where St. Laurent used to be before it was destroyed. St. Laurent was clearly the home church and cemetery of the Savoie/LeJeune family.

I suspect the majority of family members who died in the area and whose deaths are recorded in the Port Royal church’s parish records are buried at St. Laurent, especially after the cemetery at Port Royal came under English control. The Catholic church in Port Royal was burned multiple times by the English.

Of the rest of Catherine’s grandchildren, we know that at least 29 were caught up in the Expulsion, because we have at least some information about them afterwards, noted in the records above, as slim as it might be.

We find them planted in both North America and Europe once again.

In 1754, the Acadian peninsula was unquestionably held by England, and the English wanted the Acadians, who still refused to pledge allegiance to the British Crown, removed so that the much more manageable English settlers from New England could take their places and farm the fertile land.

Four years later, when the English settlers arrived, they reporting finding piles of the unfortunate Acadian’s belongings stacked on and along the wharf where they were forced to abandon them before boarding the death ships.

It’s was incredibly painful to walk here last year and realize I was standing and walking where the lives of my Ancadian ancestors were destroyed. In this very place. So deceptively beautiful if you don’t know what happened here.

Today’s beauty belies the trauma that remains on this land. If you close your eyes and listen carefully, you can hear the soldiers boots and prodding, the shoes on the wooden planks, and the tears, screams, and begging of the captives as they walked this wharf.

My heart ached as I absorbed what that actually meant to them, to their lives, an unknown future over which they had no control or imput, to their descendants, and ultimately, to me.

On July 28, 1755, the decision was made and removal orders were issued. The English began to round the Acadians up, strip them of anything valuable, and force them onto cruelly and dangerously overcrowded ships.