I’ve been struggling for years, decades actually, to identify the father of Charles Campbell of Hawkins County, Tennessee. We’re finally making progress by combining family oral history with traditional records research, Y DNA, and the process of elimination – thanks to a combination of people.

I think you’ll find the twists and turns in this journey interesting. It sure has been enlightening!

Thank Goodness for my Campbell Cousin!

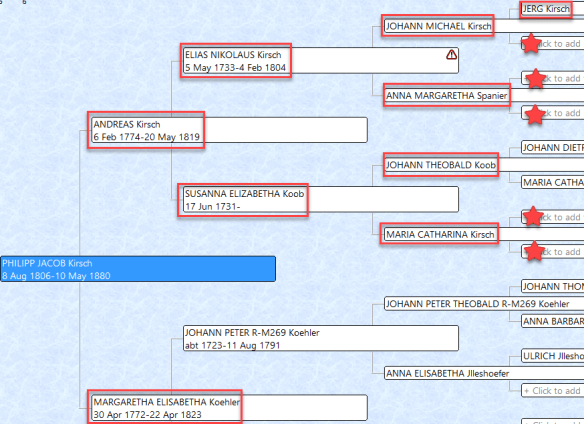

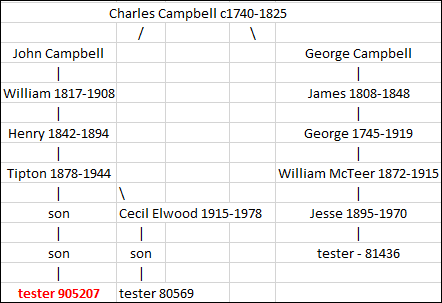

Recently, my Campbell cousin agreed to take a Y DNA test.

He descends from my John Campbell through son William Newton Campbell whose line migrated to Texas. William died in 1908 in Davidson, Oklahoma.

Sadly, both earlier testers from the Charles Campbell line have passed away, so their Y DNA tests can’t be upgraded. My Campbell cousin represented by kit 905207 has been the critical link in what I think might just be a chink in the long-standing brick wall of Charles Campbell.

And if it isn’t THE chink, it’s still chipping away at that wall.

Who Were Charles Campbell’s Parents?

Charles Campbell was in Hawkins County in 1788, in what would become Tennessee in 1796. He may have been in Sullivan County as early as 1783.

The people who settled in this part of eastern Tennessee, and specifically in the neighborhood along Dodson Creek where Charles Campbell owned land and lived most of his life arrived in what is known as the Rockingham migration.

In fact, this 1784 tax list from Rockingham County, VA shows several people who were Charles Campbell’s direct neighbors in Hawkins County, including Michael Roark whose property abutted Charles’. In addition, the Grigsbee (Grigsby) family is found nearby as well as the Kite family whose property is just down the road beside the Louderbacks.

However, looking on the 1782 tax list for Rockingham County doesn’t show Charles Campbell who was having children as early as 1770, so was assuredly an adult on personal property tax lists, someplace, by 1782, assuming he wasn’t in a wagon on his way to the next frontier.

Note that Lexington, Virginia, now in Rockbridge County, but then in Augusta County, is on the same migration path down the Shenandoah Valley – the only reasonable path from Rockingham County to the area on Dodson Creek just south of Rogersville, Tennessee.

It’s 72 miles from Rockingham to Lexington. You have to go through Rockbridge County, on the main road at that time, to get to east Tennessee from Rockingham County.

We know, from deeds, that Gilbert Campbell lived on the main road, a location at the ferry where travelers would stop to rest, and talk, and discuss the new frontier where land was available for the asking.

This is most likely the path that Charles Campbell traveled in the 1780s. But where did he come from, and who were his parents? Is there any way to make that discovery?

Y DNA Matching

Our Campbell tester matches both of the earlier two descendants of Charles Campbell, as expected, but there’s another person that this group matches as well.

At 111 markers, my cousin matches a descendant of Gilbert Campbell who wrote his will in 1750 and died in 1751 in Rockbridge County, VA.

Looking at the Campbell DNA Project, the Campbell men are part of the HUGE group 30, compromised of many, many Campbell descendants. However, look at who kit 81436, a descendant of Charles through son George, matches most closely.

Click to enlarge

Yep, Gilbert again.

The Campbell Article

All I can say is that I’m extremely grateful for the Campbell DNA Project at Family Tree DNA, because without this project, and project administrator Kevin Campbell, this brick wall wouldn’t even be threatened.

Kevin along with James A. Campbell wrote an article that was published in the Journal of the Clan Campbell Society (North America) Vol. 43, No. 2, Spring 2016.

To set the stage, two groups of Campbell families settled in Augusta County, VA in the late 1730s as land became available in the Borden tract. Both groups had as their progenitor a man named Duncan Campbell, born in Scotland. No confusion there, right?

One Duncan moved to Ulster County, Ireland and died. His descendants immigrated into Pennsylvania in 1726, then on into Augusta County about 1738, according to the article’s endnotes.

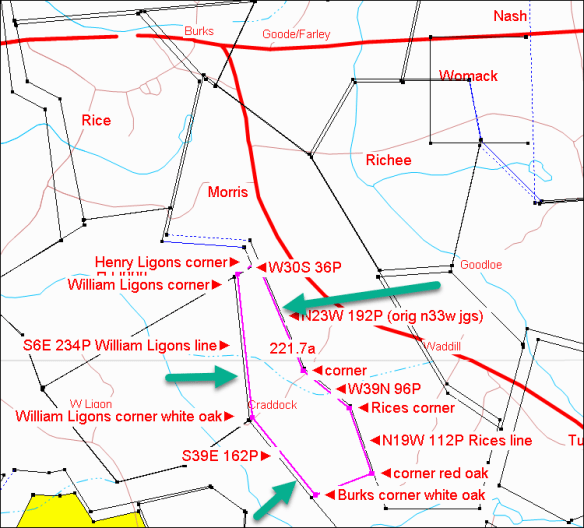

This is the group, shown along the South River where the green arrows point, that our Campbell line matches most closely.

The Tinkling Spring Church, the first formed in the area is shown as well. For many years, the minister baptized children in homes because either a church building didn’t yet exist or was too distant. He baptized Gilbert’s son, Charles, in 1741.

The second Campbell group, shown in red, settled along the North River in present-day Rockingham County, about 15 miles north of Staunton, then Orange County where we find a description of a deed in 1745. This family’s oral history relates that their ancestor, also Duncan Campbell, never left Scotland before immigrating to the colonies.

The red line is unquestionably not our line.

Gilbert Campbell’s land was located in present day Lexington, further south yet.

In the article, Kevin describes how he determined that the Campbell families of Southwest Virginia, specifically Augusta County, are actually two separate Duncan Campbell lines of Campbell men. This doesn’t mean they are unrelated historically, but it does mean their common ancestor is many generations in the past.

Thankfully, the 2 lines have developed enough mutations over time that patterns exist in both lines that set them apart from each other.

Let me review the relevant portions of the article that are pertinent both geographically and historically, as well as genetically.

This excerpt is indeed exactly how I feel about my Charles Campbell.

“Just looking at land transactions involving Charles Campbell from 1740-1770 in Augusta County and lands just south of Augusta County was disheartening. How many Charles were there? How did they relate? One needed a genealogical chart just to map Charles Campbell.

Who was, or were, Charles Campbell of Augusta County?”

The researcher who said that was Catherine Bushman who reported that there were two Charles Campbells in Augusta County in the 1740s on to past mid-century. One Charles Campbell was found on the North River who held land with Hugh Campbell at Mount Crawford. A second Charles was found on the South Shenandoah River who had multiple, sizeable land holdings. These men lived 20 miles apart.

But neither of these men can be our Charles, because our Charles died about 1825, so he would not have been alive and owning land by 1740.

But still, we have two adult males named Charles who might be the parents or relatives of my Charles. Unfortunately, neither of them appear to live in the green group.

The DNA of the North and South Augusta Campbells

Kevin compared the DNA of several males who are proven to descend from the North and South Augusta County Campbell lines.

On all 10 differentiating markers that form the signatures of the North and South groups, our Charles Campbell men match the South Campbell group, meaning that our Charles Campbell group is more closely related to Duncan Campbell whose descendants lived along the South River – the descendants of “White David” Campbell and his brother Patrick Campbell.

“White David” and Patrick were the sons of John Campbell and Grissel “Grace” Hay, who was reportedly the son of Duncan Campbell and Mary McCoy.

To the best of our knowledge, neither of these families had a Gilbert. Who was Gilbert?

Gilbert Campbell

The descendants of Gilbert Campbell have another defining group of markers that are only found among this group.

While all of the testers have tested at marker CDY, only three have tested at markers DYS710 and DYS510. The other two yellow men are deceased, of course, but it’s very likely they would match kit 905207 given their proven line of descent.

The only close Campbell line matches who carry these markers are our three men and the descendant of Gilbert plus an unidentified William born in 1750 in Virginia and died in Alabama. The closest is Gilbert and he’s in the right place at the right time.

So, where did Gilbert Campbell live and what do we know about him?

I reached out to Kevin Campbell again, and he provided what he could. There isn’t much known, but combining what he provided with what I found elsewhere, there is at least something.

Gilbert lived in the right place at the right time, in what is now Lexington, Virginia, located in Rockbridge County.

Gilbert Has a Son, Charles

Perhaps the single most exciting piece of evidence discovered about Gilbert Campbell, in combination with his location, is that he had a son named Charles.

In the book Tinkling Spring, Headwater of Freedom, A Study of the Church and her People 1732-1952 by Howard McKnight Wilson, published in 1954, we discover the following:

Page 73 – The location of this road is shown at strategic points on the original map of Maryland and Virginia made by Colonel Joshua Fry…and Colonel Peter Jefferson…in the year 1751. Leaving Philadelphia, the road went through the present location at Lancaster, PA turned southwest and crossed the Potomac at Williamsferry (now Williamsport, Maryland) and continues south by the present site of Winchester, VA. It kept to the east in the Shenandoah Valley, then down Mill Creek and across North River of the James at Gilbert Campbell’s Ford, and on toward Roanoke, turning southward just west of Tinker’s Creek on the outskirts of the present city of Roanoke.

Page 74 – Orange County, VA court order dated May 23, 1745, the Augusta County people were authorized to make the first improvements upon this road, where it fell within the bounds of the new county. Report of the commissioners is as follows: …Inhabitants between the mountains above Thompson’s Ford and Tinkling Spring do clear the same and the said road continue from Tinkling Spring to Beverley Manor line and that Patrick Campbell, John Buchanan and William Henderson be overseers and that all the inhabitants above Tinkling Spring and Beverley Manor line do clear the same and that the said road continue from Beverley Manor line to Gilbert Campbell’s Ford on the north branch of the James River and…that the road continue from Gilbert Campbell’s Ford to a ford a the Cherry Tree Bottom on the James River…and that a distinct order be given to every gang to clear the same and that it be cleared as it is already blazed and laid off with two notches and a cross…dated April 8, 1745.

Page 471 – Record of Baptisms by Reverend John Craig. Charles Campbell, son of Gilbert Campbell, October 15, 1741, at the house of Gilbert Campbell on the North Branch of the James River.

Woohoooo – look at that!!!

What other records exist for Gilbert and his wife?

In the Scotch-Irish Settlement in Virginia by Lyman Chalkey, Volume 1, page 27, we discover what was surely the high drama soap-opera of the day. Everyone who could possibly attend court would have, and those who couldn’t surely waited anxiously for the sound of hoofbeats upon the road – the first person to return so they could hear what had happened.

Of course this begs the question of the identify of Mary Ann Campbell, and was she related to Prudence in some fashion? Unfortunately, Mary Ann is still anonymous, but we do have information on the immediate family members of Gilbert, and she’s not a daughter.

Gilbert Campbell’s Family

The family group sheet provided for Gilbert Campbell by the Clan Campbell Society provides the name of the wife and children of Gilbert. Gilbert’s wife was named Prudence and is reported with a surname spelled both Osran and Puran (Chalkey pages 19 and 22), in Augusta County Court records and elsewhere as Osmun and Ozran. Prudence died before March 16, 1768. The society lists their marriage as having occurred in Pennsylvania, but the source is not mentioned, with information as follows:

Gilbert died before February of 1750 (old date, 1751 new date.)

- Son James born about 1734 in Ireland, married Elizabeth.

- Daughter Elizabeth born about 1736 in Ireland, married a Woods.

- Daughter Prudence born about 1738 in Ireland, married a Hays.

- Daughter Sarah born about 1740 in Virginia.

- Son George born October 21, 1740 and died on February 7, 1814, both in Augusta County. Married in 1765 to Agness McClure 1746-1797.

- Daughter Lettis born in 1743 in Albemarle County married John Woods. (Note that if George was born in Augusta County in 1740, it’s unlikely that Lettis was born in Albemarle.)

- Charles Campbell born in 1741.

If their date for the birth of Gilbert’s son, James, is accurate, he cannot be the father of our Charles who was born before 1750, based on the dates of the births of his sons. How the society estimated the date of James’ birth is unknown.

Land

In 1742, Gilbert purchased 389 acres of land in the Borden Tract (Forks of the James River, now in Rockbridge County,) from Benjamin Borden for 11 pounds, 13 shillings, and 4 pence. The Crossing of the North Fork of the James (now Murray) River was known as Campbell’s Ferry. Roughly a decade after building his home, Gilbert died. According to Chalkey, persons owning land adjacent to Gilbert’s were John Moore (Chalkley, v3, p263), John Allison (ibid, p. 267-8), Robert Moore (ibit, p. 272) and Joseph Walker (after Gilbert’s death) (ibid, p. 340).

This is interesting because Jane Allison married Robert Campbell, the son of John Campbell and Grissel Hay, in Rockbridge County. Robert wound up in northern Hawkins County, Tennessee and his son James was long believed to be the father of brothers George and John Campbell. I chased this James, and his children for years, and there’s not even a shred of a hint of evidence that he was the father of George and John.

However, there could have been some morsel of truth in that they could have been related.

Gilbert’s Will

The abstract of Gilbert Campbell’s will is found in Lyman Chalkley’s Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish Settlement in Virginia, Vol. 3, p.19., Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1989.

The original is found in Augusta Co. Court, Will Book No. 1, p. 294. The abstract reads as follows, along with additional information:

Page 294: 29th August, 1750. Gilbert Campbell’s will, of Forks of James River, plantationer

- Wife, Prudence Campbell, alias Osran

- Son, George (infant)

- Son Charles (infant)

- Daughter, Elizabeth Woods, alias Campbell

- Son, James

- Daughter, Prudence Hays

- Daughter, Sarah Campbell

- Daughter, Lattice Campbell

Executors, James Trimble, Thomas Stuart and Andrew Hays.

Teste: James Thompson, Robert Allison, Alex. McMullen.

Proved, 26 February, 1750 (current 1751), by Thompson and Allison, and probate granted to Andrew Hays.”

Page 308. — 27th February, 1750-51. Andrew Hays’ bond as executor of Gilbert Campbell, with sureties Charles Hays, James Walker.” (Chalkley, v. 3, p. 20).

Page 372. — 23 May 1751. Gilbert Campbell’s appraisement, by Alex. McMullan, Robert Allison, James Thompson, Andrew Hays. (Chalkley, v. 3, p. 22).

Page 373. — 23rd May 1751. Appraisment of goods left by Gilbert Campbell to his wife, Prudence Campbell, alias Puran. (Chalkley, p. 22)

Will Book No. 2. Page 243. — 17th May 1758. George Campbell’s bond (with Robert McElheny, Robt. Moore) as guardian to Lettice Campbell, orphan of Gilbert Campbell.” (Chalkley, v. 3, page 48.)

Chalkley’s Abstracts, Vol 3, p. 102: Will Book No. 4 includes the following statement: “Page 82. . . 16 March 1768. Prudence Campbell’s proven account. . . “

It’s worth noting that James is not mentioned as an infant, meaning he was born before in 1729 or earlier, so the society’s estimate of 1734 is off by several years, unless they have used age 16 as the definition of “not an infant.”

It’s interesting that no guardians were appointed for George or Charles, or those documents haven’t been preserved/discovered/reported.

While Chalkey provides the extract of Gilbert’s will, in an old Rootsweb list posting, Gilbert’s full will is provided by Tim Campbell.

1750 Page 294: 29th August, 1750. Gilbert Campbell’s will, of Forks of James River, plantationer–Wife, Prudence Osran Campbell, alias Osran; son, George Campbell (infant); son, Charles Campbell (infant); daughter, Elizabeth Campbell Woods, alias Campbell; son, James Campbell; daughter, Prudence Campbell Hays; daughter, Sarah Campbell; daughter, Lattice Campbell. Executors, James Trimble, Thomas Stuart and Andrew Hays. Teste: James Thompson, Robert Allison, Alex. McMuIlen. Proved, 26th February, 1751, by Thompson and Allison, and probate granted to Andrew Hays. Augusta County Will Book 1

A copy of this document in is Tim Campbells’ files. Gilbert Campbell left his plantation to wife Prudence until son George came of age, at which time she was to have half, then when son Charles came of age, she was to have just the house and adjacent field, i.e., the 2 boys were to receive parts of the plantation as they came of age. George was to receive the half “next to the river” and Charles was to receive the other half. Children Elizabeth, James and Prudence were to receive one crown apiece. Charles and George were to pay the other 2 siblings, Sarah and Lattice, 2 pounds each and 20 pounds was to be set aside for their well being out of the plantation.

Land Location

Rockbridge County VA Deed book A page 7, April 7, 1778 – Joseph Walker sells to William Graham 291 acres (then in Botetourt, now Rockbridge County), bounded on north by James River, corner Gilbert Campbell’s and John Moore’s.

The part of Rockbridge where Lexington is located appears to have fall into Botetourt County for about a year.

Using Borden’s land grant map located here, along with an index located here, I have been able to locate Gilbert’s land in what is now Lexington, Virginia adjacent a James Campbell who was possibly/probably Gilbert’s brother. One of James’ tracts adjoined Gilberts and another was close by.

On the detailed plat maps, here, that can’t be reproduced, tracts 198 and 184 are adjacent, while 172 is a bit more distant on the bend of the river. By searching for the names of Gilbert’s neighbors listed in deeds, you can see that the Moore, Allison and Campbell families all lived adjacent one-another.

Looking at Google maps, it’s easy to overlay the approximation of Gilbert’s land, along with that of James. The James who obtained the 434 acres of land in 1756 could have been Gilbert’s son by either age estimation, but he could also have been a brother, other relative, or unrelated. The James obtaining the 175 acres of land adjacent Gilbert’s land in 1768 could have been brother or son, but is likely related.

A Campbell researcher descended from Gilbert’s son George tells us the following:

In my visit to the Rockbridge Co Historical Society last year I learned that the town of Lexington is on Gilbert’s plantation of 389 acres. Washington and Lee Univ. sits on top of the hill where Gilbert’s home was located. Gilbert’s ferry was where the waterfall is crossing the now Maury River (renamed from North River.) Has anyone found the marriage for Gilbert and Prudence??? I found in a book at their public library that Gilbert was quite active in the Presbyterian Church. Does anyone know where in Rockbridge he is buried?

Here’s a closer view of that area.

A very, very interesting aspect of this land is that the trail may not go cold with the death of Gilbert. When Gilbert died in 1751, his will dictated that his land descend to his two sons, George and Charles when they came of age.

Additional Charles Campbell Information.

Charles, the son of Gilbert would have come of age in 1762.

Our Charles had sons John and George in about 1770 and 1772, but it’s not known how many other children he might have had, or his wife’s name.

Aside from the names of his sons, the location of his land and neighbors in Hawkins County, the only other firm piece of information that we have about Charles Campbell is that he died sometime before May 31, 1825 when a survey for neighbor Michael Roark mentions the heirs of Charles Campbell. A court record entry says that a deed of sale was to be recorded by Charles’ heirs, but it was never recorded in the deed book, and his heirs names are never given in any Hawkins County record. Nor did he have a will. So frustrating.

In Rockbridge County, formed in 1777 from parts of Augusta and Botetourt County, we find the following records:

- 1764 John Campbell committed for abusing Henry Filbrick and disrupting the court. Charles Campbell committed for abusing the court.

- 1764 Charles Campbell qualified as ensign.

- Vol. 1 March 19, 1765 – John Moore to Charles Campbell, 230 acres in Borden’s track, corner John Houston’s land, Wit William Mann, Archibald Reaugh, Samuel Downey, Delivered to C. Campbell’s executors March 23, 1827.

Note the date in 1827 when this was actually delivered to Charles’ executors.

When I saw this note indicating that Charles Campbell had died by 1827, I became very excited. Is this the same Charles Campbell who had died in Tennessee? Did he still own land, absentee, in Rockbridge County?

John Moore’s land abutted Gilbert Campbell’s. There could be two different John Moores, but this is likely Charles the son of Gilbert.

1765 Page 46.-14th August, 1765. George Campbell, Agness Campbell, his wife, and Prudence Campbell (widow of Gilbert Campbell), his mother, to Andrew McClure, £130,194 acres in Forks of James and in the fork of Wood’s Creek and North Branch of James; corner Joseph Walker. Teste: Jno. McCampbell, Charles Campbell. Delivered: grantee, September 1770. Deed book 12

This 194 acres is probably George’s part of his father’s estate. Note that Charles signs and a John McCampbell does as well, or McCampbell is actually Campbell. Andrew and William McCampbell had grants north of James Campbell who lives on the bend of the river, west of Gilbert.

Of Gilbert’s 389 acre plantation, this leaves 195 acres remaining, plus Prudence Campbell’s house and field.

1766 – Charles Campbell (Borden’s land) appointed appraiser.

Page 137 – May 20, 1766 – Charles Campbell (Borden’s land) appointed Constable.

Page 138 – Charles Campbell – certificate for hemp.

Vol 2 Page 403 – 1767 Charles Campbell listed on Borden land, also noted as a constable.

In 1768, James Campbell also obtained a certificate for hemp. He is also appointed constable.

We know that Gilbert’s son Charles’ brother was James.

Vol 3 Page 484 – May 24, 1769 John Sproul and Margaret to Alexander Wilson, 250 acres in Borden’s tract, corner Andrew Steel and William Alexander, corner Robert Telford, Robert Lowry. Wit Charles Campbell, Thomas Alexander, Robert Wardlaw

April 27, 1769 Thomas Vance and Jenat to John Campbell. 148 acres on the North Branch of James, corner Mr. Thomas Vance, Wit James Cowan, John Alison, Charles Campbell, John Shields Jr.

Given the mention of John Alison and Charles Campbell, this appears to be near Gilbert’s land. The Allisons lived adjacent Gilbert and also directly across the river. There’s a John Campbell involved. He’s not the son of Gilbert – could be be the son of James?

Page 485 – June 15, 1769 Charles Campbell and Margret to Joseph Walker, 199 acres on Woods Creek in Fork of James River, corner Arthur McClure, Joseph Walker’s line, Robert Moore’s line, Wit James Hall, Joseph Walker, Delivered Joseph Walker June 1783

This has to be Charles, the son of Gilbert. The acreage equals exactly that of his share of Gilbert’s land and the neighbors are the same. Joseph Walker was a neighbor of Gilbert Campbell. This is also the timeframe when a Charles Campbell shows up purchasing land in East Tennessee. Did he sell out to move on? The land was sold in 1769, but never “delivered” until 1783.

Between 1768 and 1771, a chancery suite was in process involving Charles Campbell (trustee) for work to be done at the New Providence Meeting House that involved Wardlaw, Houston, Moore, Walker – all familiar names. This church was founded in 1746 on land purchased by the Kennedy family. John Brown, married to Mary Moore, the “Captive of Abbs Valley,” was the pastor for 42 years, resigning in 1794. This church was about 15 miles north of Lexington.

There is a 1773 suit where John is a son of Charles Campbell, so this Charles cannot be ours because his son John was not born until between 1772 and 1775.

Page 196 – Feb. 17, 1778 – Justice in the new Rockbridge County, Charles Campbell. This is likely Gilbert’s son.

1791 – Rockbridge County, VA Deed Book B, p. 340. 11 October 1791, 270 acres from Robert Harvey and Martha his wife, heirs-at-law to Benjamin Borden dec’d of Botetourt County, VA to Charles Campbell between said Campbell’s plantation and John McCray’s land, Robert Wardlaw’s line. Signed: Robt. Harvey, Martha Harvey, Teste: William Buchanan, William Wardlaw, Wm. Wardlaw, Alexr. Sproul, Jas. Campbell, Delivered Anniel Rodgers per order of Saml. L. Campbell, one of the exors of sd. Chas. Campbell dec’d 26 March 1827.

This deed has a very similar date as the John Moore to Charles Campbell deed in 1765 that was delivered to Charles’ heirs in 1827. This deed goes further though and references Campbell’s plantation. It doesn’t say anything about Charles heirs being in Tennessee, and if this is our Charles, we know for sure that John and George were living in Claiborne County by then, and Charles Campbell was deceased by sometime in 1825 in Hawkins County. Of course, this land could have been owned absentee for all those years by Charles of Hawkins County.

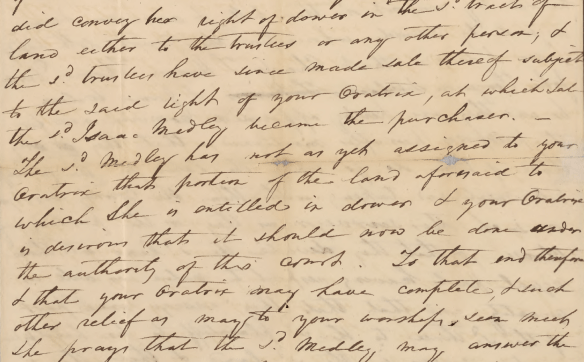

The following deposition was found in the Rockingham County Circuit Court book, page 122:

Mary Greenlee deposes, 10th November, 1806, she and her husband settled in Borden’s Grant in 1737. Her son John was born 4th October, 1738. She, her husband, her father (Emphraim McDowell, then very aged), and her brother, John McDowell, were on their way to Beverley Manor; camped on Linvel’s Creek (the spring before her brother James had raised a crop on South River in Beverley Manor, above Turk’s, near Wood Gap); there Benj. Borden came to their camp and they conducted him to his grant which he had never seen, for which Borden proposed giving 1,000 acres. They went on to the house of John Lewis, near Staunton, who was a relative of Ephraim McDowell. Relates the Milhollin story. They were the first party of white settlers in Borden’s Grant. In two years there were more than 100 settlers. Borden resided with a Mrs. Hunter, whose daughter afterwards married one Guin, to whom he gave the land whereon they lived. Her brother John was killed about Christmas before her son Samuel (first of the name) was born (he was born April, 174xxx). Benj. Borden, Jr., came into the grant in bad plight and seemed to be not much respected by John McDowell’s wife, whom Benj. afterwards married. Jno. Hart had removed to Beverley Manor some time before deponent moved to Borden’s. Joseph Borden had lived with his brother Benj.; went to school, had the smallpox about time of Benj’s. death. When he was about 18 or 19 he left the grant, very much disliked, and dissatisfied with the treatment of his brother’s wife. Beaty was the first surveyor she knew in Borden’s grant. Borden had been in Williamsburg, and there in a frolic Gov. Gooch’s son-in-law, Needler, has given him his interest in the grant. Borden’s executor, Hardin, offered to her brother James all the unsold land for a bottle of wine to anyone who would pay the quit rents, but James refused it because he feared it would run him into jail. This was shortly after Margaret Borden married Jno. Bowyer. John Moore settled in the grant at an early day, where Charles CAMPBELL now lives. Andrew Moore settled where his grandson William now lives. These were also early settlers, viz: Wm. McCandless, Wm. Sawyers, Rob. Campbell, Saml. Wood, John Mathews, Richd. Woods, John Hays and his son Charles Hays, Saml. Walker, John McCraskey. Alexr. Miller was the first blacksmith in the settlement. One Thomas Taylor married Elizabeth Paxton. Taylor was killed by the falling of a tree shortly after the marriage. Miller removed and his land has been in possession of Telford. Deponent’s daughter Mary was born May, 1745. McMullen was also an early settler; he was a school teacher and had a daughter married. John Hays’s was the first mill in the grant. Quit rents were not exacted for 2 years at the instance of Anderson, a preacher.

Wow, talk about a goldmine of historical information!

Given that in 1806 Charles Campbell seems to be still living near where his father lived, by John Moore, this seems to preclude Gilbert from being the father of our Charles Campbell.

However, our Charles could be the son of the early James Campbell, if James was the brother of Gilbert. It’s also possible that our Charles is a grandson of Gilbert through his son, James, who was apparently of age by 1750 when Gilbert wrote his will.

Rockbridge County Tax Lists

Rockbridge County Tax lists are available in some format from 1778 to 1810, so let’s see if we can find a pattern there.

| Tax List | Name | Additional Info | Comment |

| 1778 | Charles Campbell | 2 tithes | |

| Charles Campbell (possible second entry, according to a different source) | |||

| George Campbell | 2 | ||

| 1782 A (alpha list) | Charles Campbell Esq | 1 tithe, 2 slaves, Fanny, Dennis, 9 horses, 30 cattle | Alexander, John, Henry, Joseph Sr and Jr. Campbell also Crockets |

| George Campbell | 1 tithe 7 horses 12 cattle | ||

| George Campbell | 1 tithe 6 horses 17 cattle | ||

| 1783 | George | 1-0-0-6-14 | Tithes, slaves>16, slaves <16, horses cattle, |

| George | 1-0-0-7-9 | Joseph, Joseph, John, Alex with note Dougal, Duncan, Henry Campbell | |

| Charles | 1-1-1-7-28 | Slaves Jenny, Dinnis | |

| 1784 | George | 1-0-0-6-14 | Joseph, Hugh, David, |

| George | 1-0-0-6-11 | ||

| Charles | 1-1-1-9-29 | Slaves Fanny, Dennis. Other Campbells incl Alexander, Duncan, Henry | |

| 1785 | George | 0-0-0-5-10 | John, Joseph, (both no tithes), Joseph, Hugh, Andrew, Duncan, Alex, David, Robert Campbell |

| George | 1-0-0-3-4 | ||

| Charles | 1-1-1-9-28 | ||

| 1786 | Charles | 1-1-1-11-26 | Slaves Fanny and Dennis, other Campbells include Joseph, John (no tithe), Andrew, Henry, Samuel, |

| 1787A | George | 0-0-0-3-6 | Duncan, Henry, Samuel, Robert (no tithes), Alex no white tithes |

| Charles | 1-2-0-11-30 | ||

| 1787B | George | 0-0-0-3-18 | David, John, Joseph, Joseph, Andrew, Hugh |

| 1788 A | George | 1-0-0-2 | Robert, Duncan, Alex, Henry, Samuel, |

| Charles Campbell, Esq | 2-2-0-10 | ||

| 1788B | George | 0-0-0-4 | Andrew, John, Joseph, David, Hugh |

| 1789A | George | 1-0-0-2 | David, Duncan, Alex, Henry, Samuel |

| Charles | 2-2-0-11 | ||

| 1789B | George | 0-0-0-3 | Hugh, John Jr., Andrew, Robert |

| 1790A | George | 1-0-0-2 | Samuel, Henry, Henry Jr, Duncan, Alex, David, |

| Capt. Charles Campbell | 2-2-0-10 | ||

| George | 1-0-0-2 | ||

| 1790B | George | 1-0-0-4 | Alex, Hugh, John, John, Robert |

| 1791A | George | 1-0-0-2 | David, David, Duncan, Henry, Samuel, Alex |

| George | 1-0-0-2 | ||

| Capt. Charles | 3-2-0-10 | ||

| 1791B | George | 1-0-0-5 | John, John, John |

I skipped ahead to 1800 and Charles is still on the tax list. He’s easy to recognize because he seems to be wealthier and has more livestock, not to mention slaves.

Given his presence in Rockbridge County, clearly Gilbert isn’t the father of our Charles. But the name Charles clearly runs in Gilbert’s line too.

What About James Campbell?

It’s worth noting that there is no James Campbell on these early tax lists, at all, so the James who owned land in 1756 and 1768 either died or moved on. Could this James be the father of our Charles?

Depending on his age, it’s certainly possible.

The son of Gilbert named James is probably accounted for by an 1804 deed from James Campbell who lives in Kentucky in the suit John McCleland of Rockbridge County vs James Campbell involving the Hays family.

On the muster list of the year 1742 – on Capt. McDowell’s list – Gilbert Camble and James Camble are listed together, so this James was clearly of age then, meaning he could have been the father of Charles Campbell who would have been born in 1750 or earlier.

I need to work on James, in particular land sales, to see if I can figure out what happened to him.

The James Story

The oral history of James Campbell being the father of John and George Campbell took root years ago with an earlier researcher.

Several years ago, Mary Price sent me information titled “Campbell – Dobkins Connections” which she compiled in the 1960s and 1970s before her mother’s death. Unfortunately, Mary was elderly at the time and only sent me the first few pages, although she meant to send the rest and thought she had. I’m hopeful maybe she sent the entire document to another researcher who will be kind enough to share.

Unfortunately, some of the books in Claiborne County (TN) Clerk’s office that Mary accessed were missing by the time I began researching a generation later, and I fear that much of what she found may have gone with her to the grave.

Mary descended from the same John Campbell that I do. All 3 of John’s sons, Jacob, George Washington and William Newton went to Texas.

- Jacob Campbell was born in 1801 in Claiborne County, TN, had 5 sons and died in Collin County, Texas in 1879/1880.

- George Washington Campbell was born in 1813 in Claiborne County, died sometime after 1880 and had at one son, John C., born in 1845. In 1860, he’s in Collin County, TX, along with Mary Price’s relatives, in 1870 in Denton County and in 1880, in Cooke County.

- William Newton Campbell was born in 1817 in Claiborne County and died in 1908 in Davidson, Tillman County, Oklahoma. In 1870, 1880 and 1900, he lived in Denton County, Texas, He had 5 sons, all born in Tennessee and all died in or near either Tilman County, Oklahoma or Ringgold in Montague County, Texas.

Our Documented Campbell Line, According to Mary

Mary Price starts with John Campbell:

John Campbell was probably born in Shenandoah Co., Va. in the 1770s. In the 1950s a descendant of John Campbell interviewed some of his uncles in Texas who were in their eighties as to the name of John’s father. They all said his name was James Campbell as they were told by their grandparents.

That means the uncles would have been born in the 1870s and were probably second-generation Texans.

There is a James on the 1783 tax list for Shenandoah Co., Va. It is not known if he ever moved to Tennessee. Perhaps he did, to Jefferson Co., Tn., however, we have no proof. We researchers have found that there were new numerous Campbell families – all using the same first names – in almost every county searched.

We have been unable to find a will or an estate settlement for this James Campbell.

Claiborne Co., Tn. was formed in 1801 from parts of Grainger and Hawkins Co. We find our John Campbell serving on the jury in 1803. In 1802 our John purchased land in Claiborne Co., Tn. from Alexander Outlaw. Outlaw lived in Jefferson Co., Tn. and was married to a Campbell lady. This Alexander Outlaw also had dealings with our Jacob Dobkins in Jefferson Co., and also with our Dodsons in Jefferson Co., Tn.

Mary’s family was from Tom, Oklahoma, east of that area, but her grandfather, Lazarus Dobkins Dodson, according to Mary, settled in Texas in the 1880s or 1890s near the Campbell relatives. He married in Denton County in 1899 and died in Cass County in 1964.

Given the proximity, I’d wager that the Campbell men Mary mentions were the ones in Collin County. Given the people involved, they were at least 3, if not 4 generations removed from John Campbell, and of course, they had never lived in Claiborne County. Their grandparents or great-grandparents moved to Texas.

George and John Campbell’s father appears strongly to be Charles Campbell, not a James. There is no James that fits. But Charles, who lives in the neighbor county, on Dodson Creek, down the road from the Dobkins family, sells land to his sons, John and George, who jointly dispose of that land just before arriving in Claiborne County. In Claiborne, they are both married to Dobkins sisters and live very close to Jacob Dobkins, their father-in-law. Furthermore, I match 45 Dobkins descendants who descend through other children of Jacob Dobkins.

It’s not surprising, several generations removed, that Mary’s relatives remembered the name of John’s father incorrectly, but John’s grandfather may indeed have been James.

It’s worth nothing that the name Gilbert never appears in the children of John or George.

John Campbell has children:

- Jacob (his wife’s father’s name)

- Elizabeth (his wife’s sister’s name)

- Elmira

- Jane

- Martha

- Rutha

- George Washington (George is his brother’s name)

- William Newton

George Campbell has children:

- Dorcas (his wife’s mother’s name)

- Peggy

- Jenny (his wife’s sister’s name)

- Charles (his father’s name)

- James

- John (his brother’s name)

- Elizabeth (his wife’s name)

Back to Mary’s Story

The Campbell family, from which our John Campbell descended were originally from Inverary, Argylishire, connected with the famous Campbell clans of the Highlands of Scotland, and emigrated to Ireland near the close of the reign of Queen Elizabeth in about the year 1600. The Northern portion of Ireland received, in that period, large accessions of Scotch Protestants, who proved to be valuable and useful citizens. Here the Campbells continued to live for several generations until at length, the emigrant and progenitor of our Campbell Clan to America, old John Campbell arrived in 1726 in Donegal, Lancaster, Pennsylvania with 10 or 12 children.

Some of his children had already married and had children of their own. It did not take long for them to start making records. Old John Campbell’s son, Patrick who was born in about 1690 was serving as a constable by 1729.

About 1730, old John Campbell along with 3 of his sons, Patrick among them, removed from Pennsylvania to what was then a part of Orange Co., which later became Augusta Co., in the rich Shenandoah Valley of Va.

This Patrick Campbell became the ancestor of the famous General William Campbell and William brother-in-law and first cousin, Arthur Campbell. These two men were prominent men in Southwest Virginia and Northeast Tennessee during the time of our Campbell’s there.

Arthur Campbell (1743-1811) lived just over the Claiborne County, TN border in Middlesboro, KY, with his son James transacting business in Claiborne County. I chased this line for years and it’s not ours.

Our line of Campbell (John) was no doubt close kin to them, but so many John Campbells, that I cannot tie him in or document him for sure. But I do not have any doubt that this is the clan we descend from.

The Campbell family that eventually migrated to Claiborne County Tennessee is first documented with Dugal Campbell in 1490 in Inverary, Argylershire, Scotland and is the Campbell clan. His son Duncan b 1529 had son Patrick b 1550 who had Hugh b 1580 who had Andrew b 1615 who had son Duncan b 1645 who married Mary McCoy in 1672. Duncan and Mary immigrated to America with their children and grandchildren.

Their oldest son, John was born in Drumboden, near Londonderry, Ireland and married Grissel Hay, but died on the boat to America in 1725. However, they already had children, Robert b 1718 in County Down Ireland, died Dec. 24, 1810 in Carters Valley, Hawkins Valley, Tn, Archibald, Colin, William and Catharine. Some researchers show additional children.

Robert Campbell married Letitia Crockett b 1720/30 d abt 1758 in Prince Edward Co, Va. They had James Campbell b 1745/49 died before May 31 1792 in Carters Valley, Hawkins Co, Tn., Alexander b 1747, Elizabeth b 1751, Catharine b 1753, Anna b 1755, Jane b 1757, Martha b 1757, and Robert b 1761.

James and Letitia Allison, a niece of his father’s second wife Jane Allison, had John Campbell b 1772/75 d Sep 22, 1838, Elizabeth and George b 1770. James was killed by the fall of the limb of a tree while at work stocking a plow at his home in Carter’s Valley, 19 miles from Rogersville, Tn. The widow married William Pallett, settling in Warren Co.

Mary states the informatoin about John Campbell who died in 1838, meaning our John, being the son of James Campbell and Letitia Allison as fact, but it was then and is still unproven. She had found a James Campbell and assigned John to him.

I chased the Robert Campbell family too, relentlessly, for more than a decade – researching on site, finding Robert’s land and several cemeteries but not any sons of the James who died there in Carter Valley in 1792. There’s NO evidence that he’s the father of John. Nothing in the court records for orphans at his death. Nothing at all.

The land in Carter Valley is beautiful, and I was sad that I couldn’t find any evidence since Mary had seemed so sure. It was a beautiful wild goose chase:)

It is interesting to note though that Robert Campbell settled for some time in Rockbridge County, married an Allison, and is found on tax lists before moving on to Hawkins County. He probably knew Gilbert and may have been related.

However, there is absolutely no connection found between Robert’s son, James, or his widow and her second husband, to Claiborne County or any John or George Campbell. Believe me, I tried.

Given the name of Allison, and the affiliation of Gilbert Campbell with Allisons and Crockets in Rockbridge County, I’m not entirely convinced the Prince Edward County Campbell’s were terribly far removed from the Rockbridge County Campbells. They may have know they were related and may have been relatively closely related, aunt/uncle, first cousins, even undocumented siblings perhaps.

The name of James Campbell may still be important in our search, because Gilbert Campbell’s brother appears to be James, or at least a James is associated with Gilbert in some way, aside from being his son. A William Campbell lives close by too.

Y DNA would not be able to differentiate between brothers and autosomal DNA is too many generations removed. If we knew the names of James Campbell’s wife, meaning the James who was the probable brother of Gilbert, we might be able to use autosomal DNA to determine a connection with her family.

However, without additional actual documentary evidence, such as information about James, his wife or even a definitive surname for Prudence, we’re mired in the mud.

According to Governor David Campbell

The grandson of “White David” Campbell, to differentiate him from his cousin “Black David” due to his fair coloring, not as a racist designation, became governor of Virginia and thankfully recorded a great deal, in his own handwriting, which has been preserved today at Duke University.

Ken Norfleet, perhaps the preeminent Campbell researcher, quotes David as follows after providing an introduction:

THE ANCESTORS OF JOHN CAMPBELL

I have no documentary evidence which substantiates the existance of any of the early generations of Campbells prior to John Campbell (d. 1741), husband of Grace Hay. Hence, mention of these early Campbells should be carefully qualified. The early generations of Campbells shown in this genealogical report are those cited by Governor David Campbell in a note I found among his papers (see below).

NOTE OF GOVERNOR DAVID CAMPBELL OF VA

Governor David Campbell (1779-1859) of VA was a meticulous researcher and it is mainly due to his work that the story of John Campbell and Grace Hay (parents of White David) and their descendants has survived. Governor Campbell’s papers and other documents are part of the Campbell Papers Collection (about 8,000 documents) located at Duke University, Durham NC. A microfilm copy of the Campbell Papers is located at the Tennessee State Library and Archives in Nashville. In 1996, while reviewing this microfilm copy, I found the following note, in Governor David Campbell’s handwriting, on microfilm reel number 1 (my comments are in brackets):

“Genealogy – The Campbell Family

“The farthest back the Campbell family can be traced is to Duncan Campbell of Inverary, Scotland, the place where the old Duke of Argyle and most of the Scotch [sic] Campbells lived. It was in the latter part of Queen Elizabeth’s reign that Duncan Campbell moved from Inverary to Ireland. Not long afterwards, in the reign of James First, when he had come to the throne, forfeitures were declared at Ulster in 1612, and Duncan Campbell bought a lease of the forfeited land from one of the English officers. One of his sons, Patrick, bought out the lease and estate in remainder, whereby he acquired the [land in] fee simple. How many other sons Duncan may have had is not known.

“Patrick had a son Hugh, and he a son Andrew. The generations from Andrew to our great-grandfather John [husband of Grace Hay] are not stated. It should be to Duncan, father of John Campbell, [who] emigrated to America with his family in the year 1726 and settled in the Sweet Ara river where Lancaster now stands in Pennsylvania. He [meaning John Campbell, husband of Grace Hay] had six sons, Patrick, John, William, James, Robert and David. Three – to wit – John, William and James were never married. John died in in England having gone there with Lord Boyne and became [his] steward.”

LETTER OF GOVERNOR DAVID CAMPBELL TO LYMAN DRAPER

Governor David Campbell (1779-1859), in a letter to Lyman Draper, dated 12 Dec 1840, had this to say concerning the origin of his branch (White David’s) of the Campbell Clan in America (my comments are in brackets):

” … The Campbell family from which I am descended were originally from Inverary in the Highlands of Scotland – came to Ireland in the latter part of the reign of Queen Elizabeth & thence to America. John Campbell [husband of Grace Hay] my great grandfather and the great grandfather of Gen’l William Campbell of the Revolution came from Ireland with a family of ten or twelve children, leaving behind him only one son, and settled near Lancaster in Pennsylvania in the year 1726. His eldest son Patrick was the grandfather of Gen’l William Campbell. His youngest son David [White David] was the father of Col Arthur Campbell and my grandfather. So that Gen’l Campbell and myself were second cousins. The family remained in Pennsylvania but a few years and then removed to the frontiers of Virginia, in that part which afterwards formed the county of Augusta. Here they lived many years. John Campbell (my father) the eldest son of David and Col Arthur Campbell the second son were born, raised and educated in this county. Gen’l William Campbell was also born, raised and educated here. …” [see Draper Manuscripts, Kings Mountain Papers, 10DD6, pages 1 and 2.]

From my own research, I can place these Campbells in Beverley Manor by 1738 – in that year Patrick Campbell acquired 1546 acres of land in the Manor. John Campbell (husband of Grace Hay) died in about 1741 as his estate was appraised/inventoried in that year. In summary, based on my own research among the records of Orange and Augusta Counties VA, Governor David Campbell’s story of the origins of his family in America appear to be entirely reasonable.

E-MAIL MESSAGE OF DIARMID CAMPBELL RE ANCESTORS OF JOHN CAMPBELL

Date:01 January 1998

” …although a number of people have attempted research in Ireland absolutely no further information has appeared about the ancestry of Duncan Campbell who married Mary McCoy.

“Pilcher states quite clearly at one point in her book that her information on those earlier (likely fictitious generations going back to Inverary) were taken by her from an elderly relation who thought she remembered that information. Pilcher had not intended to publish her book and it might have been better had she not, since the misinformation has misled so many and God knows how many family histories have now been published giving her bogus material as their source. Her later material appears to be more sound, although since she often gives no sources or references (as to where material was found), it means that anyone of the descents of those whom she outlines has to re-do the research.

“I have also thought that there might be some connection between the Drumaboden and the 18th century Virginia Campbells. But none has as yet appeared. Two professional research efforts in Ireland have so far been conducted, one just completed and the other in the ’80s.These were conducted by getting a group of descendants to put up some funds each and were coordinated through the Genealogists of the Clan Campbell Society of the time. While both were helpful in clarifying where no information could be found (so making easier any future research efforts), neither produced any clarification on the ancestry of either family going back from Ireland to Scotland.

“If you want the results of the second research effort you could write to the Society Genealogist, Dr.Ruby G. Campbell PhD, 3310 Fairway Drive, Baton Rouge LA 70809 USA, and ask her to let you know what to send her for the photocopying and mailing costs. But the information is not, I seem to remember, directly concerned with Drumaboden. …

” … There are in fact three sets of Northern Irish Campbells who may or may not be connected: Drumaboden, Duncan and his cousin Dugald Campbell, and the 18th century Virginia Campbells descended from one John Campbell who came over to Pennsylvania at a fairly advanced age in the 1720s or 30s.”

What Does This Mean, Exactly?

You may be wondering right about now what all of this means, to me. You might be wondering why I just didn’t stop when I discovered that Gilbert’s son, Charles never left Rockbridge County.

Clearly, my Charles in Hawkins County can’t be Gilbert’s son – so why didn’t I just throw in the towel and call it a day?

Negative evidence isn’t all bad, even though it’s disappointing when we were hoping for something more.

Let me just say that I’m really grateful that I did the extra research NOW, not in Rockbridge County in 3 weeks, because that’s where I was headed.

To be quite clear, it’s still possible that my Campbell line descends from James, Gilbert’s probable brother or possibly Gilbert’s son, James – although that’s much less likely, given his age. I need to find deed records for the earlire James selling his land to determine what happened to him, and if he can potentially be the father of my Charles.

However, even if we don’t know the identity of Charles Campbell’s father, YET, we know one heck of a lot more now than we did before this exercise, such as:

1 – We know that we don’t match the North River Campbells, and I can disregard those lines.

2 – We know that we DO match the following South River line in some way:

- Duncan Campbell and Mary Ramsey

- John Campbell (the immigrant) and unknown wife

- John Campbell (1645) and Mary McCoy

- John Campbell (1674) and Grace/Grizel Hay, immigrated to Pennsylvania in 1726. They had 6 sons. John died in England and James in Ireland, leaving Robert and William who never married, along with Patrick and “White David.”

3 – We know that we match Gilbert’s Y DNA more closely than any other lineage, represented by descendants of the South River group in Augusta County through John and Grace’s sons David and Patrick Campbell.

4 – We have discovered a unique Y DNA “signature” in our line that will assuredly help us unravel future matches – and may lead to another match that is even more revealing.

5 – We have identified a James Campbell to follow. Given the close geographic proximity of James to Gilbert, as well as the “rumor” of James in our line, in addition to the fact that George named a son James – the James who owned land adjacent to and near Gilbert may in fact still be a good candidate. In fact, right now, he’s our best candidate!

I’d love to discover more about that James Campbell and locate a Y DNA descendant to test.

Seeking James Campbell

Do you descend from a James Campbell found in Orange, Augusta or Rockbridge County, Virginia in the 1740s through 1770s? Did he own land on the James River sometimes after 1756 and before 1782?

We know by 1782 that James wasn’t living in Rockbridge County, because he’s absent from the tax lists.

Do you know the name of the wife of the James Campbell who was associated with Gilbert Campbell?

Do you descend from Gilbert Campbell and his wife, Prudence?

If you descend from the Augusta, Rockingham or Rockbridge County Campbells or from the Lancaster County, PA lineage, have you DNA tested?

I’d love to hear from you.

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- FamilyTreeDNA

- MyHeritage DNA only

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload

- AncestryDNA

- 23andMe Ancestry

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists for genealogy research