Sometimes late at night, just before I go to bed, I check MyHeritage for Record Hints and Ancestry for those little green leaf hints.

One recent midnight, I noticed a hint at Ancestry for William Crumley II. Of course, I have to have three William Crumley’s in a row in my tree.

Clicking on this hint revealed West Virginia Wills.

Of course, the first thing I noticed was that West Virginia wasn’t formed as a state until 1863, but I also know that counties and their earlier records “go with” their county into a new state. Berkeley County was formed from Frederick County, Virginia in 1772.

However, William Crumley II died between 1837 and 1840 in Lee County, Virginia, so I wasn’t very hopeful about this hint. Nonetheless, I clicked because, hey, you never know what you might discover. That’s why they’re called hints, right?

Hint 1 – The Will Book

I discovered the Berkeley County Clerk’s Will Book where William Crumley the first’s will had been dutifully copied into the Will Book on pages 185 and 186 after it was “proved” in court by witnesses on September 17, 1793. Witnesses who proved a will swore that they saw him sign the original and the will submitted was that same, unmodified, document.

This William Crumley is not William Crumley II, where this hint appeared, but his father, who did not have this hint.

I’ve been in possession of that will information for several years, so there was no new information here.

While I always read these wills, even when I have a typewritten published transcription, I know that the handwriting and the signature is not original to the person who wrote the will. The handwriting is that of the clerk.

To begin with, the signature of the deceased person can’t possibly be original after he died. William’s will was written and signed on September 30, 1792, almost exactly a year before it was probated on September 17, 1793. William was clearly ill and thinking about his family after his demise.

Given that court was held every three months, William likely died sometime between June and September of 1793.

I really wish Ancestry would not provide hints for a 1792/3 will for a man who died between 1837 and 1840.

My ancestor, William II who died in about 1840 is at least mentioned in his father’s will as a child. However, if I saved this will to William II from this hint, Ancestry would have recorded this event as his will, not the will of his father, so I declined this hint. I did, however, later connect this document to William I, even though Ancestry did NOT provide this document as a hint for him.

Hint 2 – 1764 Tax List

I clicked on the next green leaf hint for William II. A tax list for 1764. Nope, not him either given that William II wasn’t born for another three years.

Next.

Hint 3 – Executor’s Bond

Something else from Berkeley County attached to the wrong person, again.

Bother.

What’s this one?

Executor’s bonds for William Crumley’s estate who died in 1793. Now this is interesting because the bond includes the signatures of the executors, including William’s wife Sarah. I got VERY excited until I remembered that Sarah was William’s second wife and not my ancestor.

Not to mention this record dated in 1793 is still being served up on the wrong William Crumley – the same-name son of the man who died in 1793.

Worse yet, these hints did NOT exist on the correct William Crumley the first who I wrote about, here.

Ok, fine.

There’s one more hint for William II before bedtime.

Hint 4 – Berkeley County AGAIN

What’s this one?

I saw that it was from Berkeley County and almost dismissed the hint without looking. By that time, I was tired and grumpy and somewhat frustrated with trying to save records to the right person and not the person for whom the hints were delivered.

Am I EVER glad that I didn’t just click on “Ignore.”

Accidental Gold

Staring at me was the ORIGINAL WILL of William Crumley the first in a packet of Loose Probate Papers from 1772-1885 that I didn’t even know existed. I thought I had previously exhausted all available resources for this county, but I clearly had not. I’m not sure the contemporary clerks even knew those loose records existed and even if they did, they probably weren’t indexed.

Thankfully, they’ve been both scanned and (partially) indexed by Ancestry. They clearly aren’t perfect, but they are good enough to be found and sometimes, that’s all that matters. I’d rather find a hint for the wrong person so I can connect the dots than no hint at all.

My irritation pretty much evaporated.

There’s additional information provided by Ancestry which is actually incorrect, so never presume accuracy without checking for yourself. The date they are showing as the probate date is actually the date the will was executed. If I were to save this record without checking, his death/probate would be shown as September 30, 1792. That’s clearly NOT the probate nor William’s death date.

Not to mention, there were many more than 3 additional people listed in this document. There was a wife, 15 children, and the 4 witnesses to the will itself. I actually found another two names buried in the text for a total of 22 people.

Always, always read the original or at least the clerk’s handwritten copy in the Will Book.

Originals are SELDOM Available

I’ve only been lucky enough to find original wills in rare cases where the will was kept in addition to the Will Book copy, a later lawsuit ensued, or the will surfaced someplace. The original will document is normally returned to the family after being copied into the book after being proven in court.

For some reason, William’s original will was retained in the loose papers that included the original estate inventory as well. That inventory was also copied into the will book a couple of months later. Unfortunately, I’ve never found the sale document which includes the names of the purchasers.

Normally, the original will is exactly the same as the clerk’s copy in the Will Book. It should be exact, but sometimes there are differences. Some minor and some important. The will book copy is normally exact or very close to a copy transcribed by someone years later. Every time something is copied manually, there’s an opportunity for error.

Therefore, I always, always read the will, meaning the document closest in person and in time to the original, just in case. You never know. I have discovered children who were omitted in later copies or documents.

In his will, William stated that he had purchased his plantation from his brother, John Crumley. Their father, James Crumley had willed adjoining patented land to his sons, John and William. I was not aware that William had purchased John’s portion, probably when John moved to South Carolina about 1790.

William states that his plantation should be sold by the executors. The purchaser was to make payments but the land “not to be given up to the purchaser till the 26th of March in the year 1795 which is the expiration of John Antram’s (?) lease upon it.” It’s unclear whether William was referring only to the plantation he purchased from John, or if he’s referring to the combined property that he received from his father and that he purchased from John as “his plantation.”

This also tells us that William clearly didn’t expect to live until the end of that lease. The fact that the land was leased was probably a result of his poor health even though he wasn’t yet 60 years old. This also makes me wonder how long he had been ill.

William also explicitly says he has 15 children, then proceeds to name them, one by one. Unfortunately for everyone involved, William’s youngest 10 children were all underage, with the baby, Rebecca, being born about 1792.

William probably wrote his will in his brick home, above, with a newborn infant crying in the background. Sarah, his wife must have been distraught, wondering what she would do and how she would survive with 10 mouths to feed, plus any of his older children from his first marriage who remained at home. The good news, if there is any, is that the older children could help. Sarah was going to need a lot of help!

I surely would love to know what happened to William.

I can close my eyes and see the men gathered together, sitting in a circle that September 30th in 1792. It was Sunday, probably after church and after “supper” which was served at noon. William might have been too ill to attend services.

Maybe one man was preparing a quill pen and ink at a table. William spoke thoughtfully, perhaps sitting on the porch or maybe even under the tree, and the man inked his feather and wrote. You could hear the feather scratch its way across the single crisp sheet of paper. William enunciated slow, measured words, conveying his wishes to the somber onlookers who would bear witness to what he said and that, at the end, when he was satisfied, they had seen him sign the document.

From time to time, someone would nod or clear their throat as William spoke. At one point, the scrivener made a mistake and had to scratch out a couple words. Or perhaps, it wasn’t the scrivener’s error. Maybe William misspoke or someone asked him if he really meant what he said. It’s heartbreaking to write your will with a house full of young children. He knew he was dying. Men of that place and time only wrote wills when they knew the end was close at hand.

Of course, we find the obligatory language about Sarah remaining his widow. He tried to provide for Sarah even after his death. Sarah was 15 years or so younger than William and died in 1809 when she was about 59 years old. Her baby would have been about 17 years old, so she was about 40 or so when William wrote his will and died, with a whole passel of kids.

William appointed one David Faulkner, probably related to his brother John’s wife, Hannah Faulkner, along with his wife, Sarah Crumley, as his executors. Sarah’s stepfather was Thomas Faulkner, who was also her bondsman. David may have been her brother, so William probably felt secure that Sarah’s interests would be looked after.

The selection of executors may tell us indirectly that son William Crumley II had already left for the next frontier, Greene County, TN. William II was listed on the Berkeley County tax list in 1789, but not again, suggesting he had already packed up and moved on, probably before his father became ill.

But here’s the best part, on the next page…William Crumley’s actual original signature.

I wonder if this was the last time he signed his name.

Signature Doppelganger

It’s extremely ironic that the signature of his son, William Crumley the second, looks almost identical to the signature of William the first, above. We know absolutely that this was the signature of the eldest William, and we know positively that later signatures in 1807 and 1817 in Greene County, Tennessee were his son’s.

This nearly identical signature of father and son suggests that perhaps William Crumley the eldest taught his son how to write.

The family was Quaker. We know William’s father, James Crumley was a rather roudy Quaker, and William the first married Quaker Sarah Dunn in 1774, after his first wife’s death. That marriage is recorded in the Quaker minutes because Sarah had married “contrary to discipline” which tells us that William Crumley was not at that time a Quaker, or had previously been dismissed.

Quakers were forbidden from many activities. If you were a Quaker, you couldn’t marry non-Quakers, marry a first cousin, marry your first spouse’s first cousin, marry your former husband’s half-uncle, administer oaths, do something unsavory like altering a note, purchase a slave, dance, take up arms, fight, game, move away without permission, encourage gambling by lending money, train or participate in the militia, hire a militia substitute, attend muster, or even slap someone. Every year, several people were “disowned” for these violations along with failing to attend meetings, failing to pay debts, moving away without settling business affairs, or helping someone else do something forbidden, like marry “contrary to discipline.” Heaven forbid that you’d attend one of those forbidden marriage ceremonies or worse yet, join the Baptists or Methodists!

It’s unknown if William returned to the Quaker Church although it’s doubtful, because in 1774 Sarah is listed as one of the persons “disowned” for marrying him, and there is no reinstatement note or date. Furthermore, in 1781, William was among the Berkeley County citizens who provided supplies for the use of the Revolutionary armies.

One certificate (receipt) dated September 30, 1781 indicated that he and three others, including his wife’s brother William Dunn and her stepfather Thomas Faulkner were entitled to 225 pounds for eleven bushels and a peck of wheat.

We also know that William Crumley owned a slave when he died and Quakers were prohibited from owning slaves based on the belief that all human beings are equal and worthy of respect. Regardless, many Quakers continued to own slaves but purchasing a slave, at least at Hopewell, caused you to be “disowned.”

Still, William may have sent his children to be educated at the Quaker school given that the Quaker school was the only educational option other than teaching your children yourself. Quaker schools were open to non-Quaker children. We know, based on the books ordered in the 1780s for local students in multiple languages that the school was educating and welcoming non-Quaker children too.

The Hopewell Quaker Meeting House (church) built an official schoolhouse in 1779, but it’s likely that school had been being conducted in the Meeting House before a separate school building was constructed. By that time, William Crumley the second would have been 12 years old and had likely already been taught the basics, perhaps by his father.

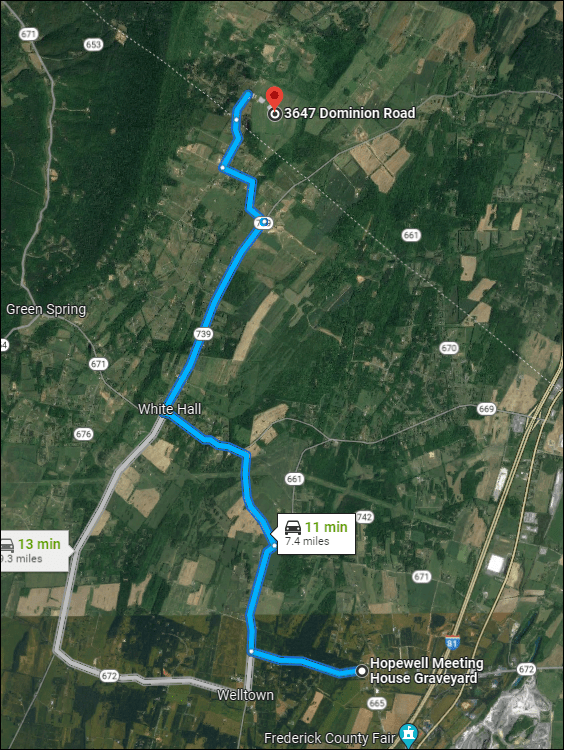

Of course, the William Crumley family at some point, probably in 1764 when William’s father James Crumley died, if not before, had moved up the road and across the county line to Berkeley County which was about seven and a half miles from the Hopewell Meeting House (and school). That was quite a distance, so William the first may have been instructing his own children, making sure they knew how to read and write and sign their names.

No wonder his son’s signature looks exactly like his.

Education and the Hopewell Meeting House

In 1934, the Hopewell Friends History was published to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the church which provided a great deal of historical information about the church itself, that part of Frederick County and the Quaker families. Unfortunately, the notes from 1734 to 1759 were lost when the clerk’s home burned, along with most of the 1795 minutes later.

Based on his will, William clearly placed a very high value on education. He instructed that his “widdow Sarah Crumley shall rays my children together to give them learning out of the profits that arises from my estate, the boys to read, write and cifer, the girls to read and write.” Apparently, females weren’t perceived to need “cifering.”

William himself would have attended school at Hopewell after his family moved from Chester County, PA in 1744 when he was 9 or 10 years old.

William’s children, following in his footsteps, may well have attended the Hopewell School or perhaps another brick school that existed near White Hall, about halfway between The Crumley home and the Hopewell Meeting House, although it’s unclear exactly when that school was established.

Many Quakers mentioned in the 1800s in the church notes are buried at what is now the White Hall United Methodist Church on Apple Pie Ridge Road. The earliest burial there with a stone is 1831 which seems to be when headstones began to be used in the area.

William also directed his funeral expenses to be paid, of course, and his executors sold a steer to pay for his coffin.

It’s doubtful that William is buried here, in the Hopewell Cemetery, unless he reconciled with the church. William’s parents are most likely buried here. His father, James, died in 1764 and his mother, Catherine, died about 1790. William would have gazed across this cemetery as a child attending services and stood here during many funerals, possibly including the service of his own first wife, Hannah Mercer, and perhaps some of their children.

I wonder if it ever occurred to him as a child that he might one day rest here himself.

No early marked graves remain before the 1830s, but people had been buried here for a century in unmarked graves by that time.

I can’t help but think of William the first, as a child, probably attending school in this building, peering out these windows, after his family moved from Pennsylvania in the early 1740s. He worshiped here on Sundays. Perhaps his son, William II and his older children attended school here some three decades later.

This stately tree in the cemetery was likely a sapling when William was a young man.

Given that William seems to have left the Quaker Church, willingly or otherwise sometime before 1774 and probably before 1759, it’s much more likely that William is buried in the cemetery right across the road from his home in an unmarked grave adjacent and behind what is now the Mount Pleasant United Methodist Church.

I don’t know, but I’d wager that this is the old Crumley family cemetery.

Perhaps William was the first person to be buried here, or maybe his first wife or one of his children. His brother, John, may have buried children here too.

Almost Too Late

Thank goodness William’s original will was microfilmed when it was, because the pages were torn and had to be carefully unfolded and repaired. William’s will might have been beyond saving soon. After all, his will had been folded several times and stored in what was probably a metal document box, just waiting to be freed, for more than 225 years.

There is information on these original documents that just isn’t available elsewhere.

It’s interesting to note the legal process that took place when wills were brought to court when someone died. The clerk wrote on the back of the will, below William’s signature, on what would likely have been the outside of the folded document that the will had been proven in open court (OP), he had recorded and examined the will and that the executors had complied with the law and a certificate was granted to them.

I believe the bottom right writing is No. 2 Folio 185 which correlated to the book and page.

It’s nothing short of a miracle that William’s original will still exists and got tucked away for posterity. I’m ever so grateful to Mr. Hunter, that long-deceased Clerk of Court who is responsible for resurrecting William’s signature, the only tangible personal item of William’s left today, save for a few DNA segments in his descendants.

Flowers, looking into the window of the Hopewell Meeting House.

_____________________________________________________________

Follow DNAexplain on Facebook, here or follow me on Twitter, here.

Share the Love!

You’re always welcome to forward articles or links to friends and share on social media.

If you haven’t already subscribed (it’s free,) you can receive an email whenever I publish by clicking the “follow” button on the main blog page, here.

You Can Help Keep This Blog Free

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Uploads

- FamilyTreeDNA – Y, mitochondrial and autosomal DNA testing

- MyHeritage DNA – Autosomal DNA test

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload – Upload your DNA file from other vendors free

- AncestryDNA – Autosomal DNA test

- 23andMe Ancestry – Autosomal DNA only, no Health

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

Genealogy Products and Services

- MyHeritage FREE Tree Builder – Genealogy software for your computer

- MyHeritage Subscription with Free Trial

- Legacy Family Tree Webinars – Genealogy and DNA classes, subscription-based, some free

- Legacy Family Tree Software – Genealogy software for your computer

- Newspapers.com – Search newspapers for your ancestors

- NewspaperArchive – Search different newspapers for your ancestors

My Book

- DNA for Native American Genealogy – by Roberta Estes, for those ordering within the United States

- DNA for Native American Genealogy – for those ordering outside the US

Genealogy Books

- Genealogical.com – Lots of wonderful genealogy research books

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists – Professional genealogy research

Discover more from DNAeXplained - Genetic Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

“Clickers” accept this type of hint without reading/thinking/doing the math. I get them by the wagon load because Everyone has a John! And hints for Jane Smith who actually died as Jane Jones. Married women are not buried with their maiden name with no mention of a married name. The grave stone of Molly Smith is not the grave stone of Molly Bailey.

Absolutely beautiful! Thank you for sharing this discovery and in so beautiful a way.

That’s a wonderful find for us Crumley descendants! What a thrill to see the actual signature. I did want to point out one thing about my John Crumley, brother of your William. John did marry a Hannah but it is very doubtful she was a Faulkner. From an account written in 1872 by Aaron H. Griffith, he states that William and John’s sister Mary was the one who married a Jesse Faulkner. (Though even this is questionable as Mary is known to have married a Doster. It’s possible, however, that she married twice.) Then Griffith later mentions that John Crumley sold land to his brother-in-law Jesse Faulkner. Clearly the connection was through the Crumley family (John’s sister’s husband) as he’d already stated. But someone took it to mean Hannah was actually a Faulkner and so it has become tradition and found in trees everywhere. I have done considerable research into John’s wife Hannah. All record associations, naming patterns, and significant triangulated autosomal DNA segments (20-70 cMs) point to Hannah being an Inman, the daughter of Benjamin and Jemima Inman of Frederick Co VA and Newberry Co SC. More can be found on Wikitree at https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Unknown-386956.

Thank you for this and kudos to you for doing the triangulation work to pinpoint the Inman DNA!!!

Interesting and well researched, as always. Love your thought process.

Great article! I am working on something similar at the moment, reading trough my Lock ancestor’s wills and Land estate division deeds from colonial era Philadelphia. But in my case, it appears I am the first researcher working with these documents, so I am taking extra care with my transcriptions and clearly marking text that I am unsure of. How nice it was to see in this post some early examples of pre-printed (type set) forms.

Hi Roberta, This article struck a chord both for the thrill of discovery and the frustration of incorrect hints. I also want to mention that I have Quaker ancestors named Mercer and I wonder if your Hannah Mercer and my Mercer’s could be related. I’m working on it and will let you know. One interesting note, the surname Mercer was sometimes given to a son as a first name. It was sometimes spelled Messer for both surnames and first names. So anyone looking for that name should look for both spelling variations.

That would be exciting. Please do let me know. There’s a Messer/Mercer research group at Facebook if you are interested. https://www.facebook.com/groups/609006616788895

Hi Roberta,

I have been working on a document to share with you detailing my research results. I don’t know how to send it to you. It doesn’t appear that I can attach anything here. Please let me know.

I have been reading your blog for several years and have learned so much, and gotten to know you as you have shared your discoveries, your family, and your life. You don’t know me at all, but I still feel close to you.

By the way, congratulations on your recent awards. Well done!!

I thought it would be so cool if I ended up related to you. I did find that we are connected by marriage, but I was unable to confirm if we are related by blood through your Hannah Mercer and my Elizabeth Mercer. But in the process, I took my tree back one generation further on that line which was exciting, and I found some interesting things on your line, such as about your William Crumley’s second wife, Sarah Dunn (Hannah’s successor after she died). As well as other interesting tidbits. I wrote it all up as sort of a chronological research log, which I would like to share with you.

I don’t want to give out my email in the public comments, but I think you can see it. You may not want to give out your email, either. But let me know if there is another way to attach a document and share it with you.

Thanks, Tammie

You can’t attach documents here. I can see your email and will reach out to you. Thank you.