Granddaughter, can you feel me beside you here today?

Can you sense my presence?

Can you hear me as I tell you my story about the death ship – the Zee Ploeg?

Have you come back for me?

Bless you, child.

Listen.

Listen…

You can hear my whispers on the cool Nordic winds that whip through your hair. It’s not the wind. It’s the breath of time and the power of memory.

It’s me.

I am standing with you as you look out over the fjord where my life, and that of my wife and her parents unfolded in unimaginable tragedy.

I tried, oh how I tried to tell you the story.

It was there, right there, in the North Sea.

Can you feel me near you?

I am here with you.

Your mother was born half a century after I died. She never knew my name, nor did her father.

But you do.

You found me, and then found my truth.

I am so relieved that someone is interested in my life, although I passed over some 147 years ago this past spring.

My name is Jacob Lenz, or at least that’s how it was spelled in Germany.

The original document is in the “Weinstadt city archive”, which kindly gave permission for the reproduction. Document was graciously retrieved by Niclas Witt.

You can see that’s how I signed my immigration papers before I left my home village of Beutelsbach, but I’m getting ahead of my own story.

In Ohio, where I settled in 1829 or 30 after a long, long journey of 12 or 13 years, it was spelled Lentz, because that’s how it sounds. Since that’s what’s on my tombstone in the Happy Corners Cemetery, that’s how you spell it today of course.

In Ohio, I bought land that I had only dared to dream of in Germany, near the cemetery where you first found me, but that’s not where I began my life. It was an incredibly difficult journey. We nearly didn’t make it. In fact, not all of us did.

Life Began in Germany

I was born in the small town of Beutelsbach, Germany on May 15th in the year of our Lord 1783.

The old Hans Lenz family home stood for a long time after I left.

My birth was recorded in the local church records and I grew up there, a good Lutheran boy.

You can see the church in the middle of the village, even today, surrounded by those beautiful vineyards.

I began working in the vineyards as soon as I was old enough, just as my ancestors for time immemorial had done – trimming the vines, harvesting the grapes and making wine.

I don’t remember ever not being in the vineyards. From the time I was first able to toddle, I went with my parents each morning and all of the village residents, most of whom were family, were working there too. I grew up in those vineyards among the grapes.

It was a good life as a vinedresser, well, until it wasn’t anymore. The wars and devastation took a terrible toll.

And then, those dreadful years descended upon us like a plague of locusts. One would think God himself was angry. The crops failed and finally, in 1816, summer never arrived. At all.

There were no grapes, nor any other food. No crops. Some of our neighbors thought that the Biblical end of times was upon us. Hunger was our constant companion. So was the fear of death. We suffered.

Can you imagine how terrible it is to witness the hunger of your wife, children and parents and be unable to do anything to ease their suffering? Oh, the ache in my heart was far worse than the pain in my belly.

Finally, the King of Wuerttemberg lifted the restrictions on emigration because there were too many hungry people in Germany. Maybe some would leave, reducing the number of people who sought relief and who pathetically begged for food when there was none to be had.

I turned 33 years old the 15th of May in 1816 although I was far too worried about the unrelenting cold weather to remember by birthday. Crops in the vineyard had already failed for the past three years, and 1816 promised to be even worse.

I had married Frederica Ruhle in our little village church more than a decade before. Our oldest son, Jacob Franklin turned 10 in November of that year with no summer, but there was no celebration. By the time November rolled around, everyone knew something was terribly wrong and that there would be no food to survive the winter.

Worse yet, on a cold day in August, yes, a cold day in August – August 22nd, 1816, Frederica gave birth to our daughter Barbara. I’ll never forget, because there wasn’t enough food for the children we already had, yet God blessed us with another.

What was a father to do?

As our plight became increasingly desperate, I realized that the sun would never arrive and we would descend into the winter darkness with the crops never maturing. Tragedy would follow as starvation came knocking at our doors. Riots over the small amount of food available, even flour, were already occurring in the cities. Desperation abounded. The grim reaper was waiting like a gleeful vulture.

I looked over the mountains and down the rivers, and although I was afraid, I knew that America would be our Salvation.

America!

America!

Some of the Separatists in the neighbor village, Schnait, had already left a year or two before and wrote letters home encouraging us to join them. Maybe we should follow. Maybe they were right. It seems that God has smiled upon their countenance, but not ours.

In February of 1817, with no bread in the house, I no longer had to dream. I was done with dreaming and praying, seemingly to no avail, so I acted.

In order to receive permission to emigrate, Wuerttemberg citizens had to pay all of their debts and advertise publicly for any unpaid debts. I paid everyone, although we had to sell almost everything, but we received permission to emigrate and I knew we must leave very soon – before someone changed their mind and before what few provisions we had were exhausted. The horrible demon breath of starvation was hot upon our necks.

To America

We weren’t traveling to America alone.

Frederica’s parents, Johann Adam Ruhle and Dorothea Katharina Wolfin joined us. They were old by then. Dorothea Katherina – we called her Katharina – was about 62 and Adam was 53. Everyone had been suffering for the past 4 years, but 1816 was the worst. Knowing the future was bleak and uncertain, we took our family with us. We could care for them in America. We couldn’t even provide for ourselves in Germany.

Besides, Frederica’s two brothers, Jacob Christian Breuning, 34, and Johann George Ruhle, 23, who had never married were leaving with us too, as well as her sister, Johanna Margaretha Ruhle, age 17, and many hands makes light work. We would own land in America.

Land!

Land of our very own and we would work it together as a family! We would grow grapes! I could smell that earthy soil as I stood, eternally hungry, in Germany. Yes, yes, America was the answer!

A large group of people, 75 or more, was leaving together from Beutelsbach and Schnait, most of us related one way or another. After all, our families had lived there forever and you could see from one side of the village to the other. You could even see the next village and walk there easily, about a mile or maybe 20 minutes – if you didn’t stop at anyone’s house along the way to talk. Of course, that seldom happened.

The vineyards grew on the hillsides behind the houses, and people from both villages walked to the vineyards everyday to tend the vines and grapes.

But the spring of 1817 was different.

Before the green sprouts of spring leaves emerged, or should have, Frederica and I, we packed our few belongings, gathered our four children together and said our goodbyes all around, knowing it was the last time we would ever see our German family members. It was heartbreaking.

Perhaps some of them would follow us to America. We were hopeful. We told them we would write and the minister could read them our letters.

Of course, what we didn’t know is that not all of us would make it to America. The price of passage would be death for many.

What would we have done had we known?

I don’t know.

Heilbronn

The village of Beutelsbach grew up beside the river, Rems, between the river and the mountains long before written records. We floated down the Rems to the Neckar River to Heilbronn, where we met up with other immigrants. A large barge would be loaded with emigrant families and whatever they were taking along, which wasn’t much, I assure you. Space was very limited and we had sold everything except for a few clothes.

In the village of Heilbronn, we stayed at the inn named Zum Kranen, The Crane, while the barge was loaded, by crane, with immigrants and our meager possessions for the trip to Amsterdam.

On April 30th, as we tried to wait patiently, a commissioner, Friedrich List arrived and asked us why we were leaving Germany. (1) Adam Ruhle, my father-in-law, an outspoken man, probably uttered more than he should have:

“You just have to look at the tax documents and you will find out by yourselves [the reasons for] our complaints. From a land property of 6 Morgen [according to Wikipedia, a Morgen in Wurttemberg was about 3500 square meters = 37700 square feet] I had to pay 279 Gulden taxes in 3 years. The king`s tax amounts to almost nothing, but the local taxes is exorbitant. If you complain about it, the district mayor does not respond. The citizens are not allowed to look at things.”

Another man from our village, Georg Friedrich Hähnle, had assets remaining of 1000 Gulden and he said:

“The forestry district does not even give greenery to the citizens, and there is also a shortage on dung. If all citizens were able to seel, then half of all citizens would emigrate. The head forester does not either give out wood. Hence people have to take it by theirselves, which is punished immoderately. If one would like to talk about everything [meaning: about all complaints], one would not be finished today.”

And another, Johann Georg Dentler, said:

“The forester treats us despotically. Two years ago, we had to collect the wood, without being allowed to take even a single stick home with us. There is no vine since four years, which has ruined the [lives of the] vintners.”

And yet another, Daniel Gaup:

“The taxes are unbearable and the worst is the sculduggery. Since half a year, a complaint against the district mayor has been filed to the authorities, and the plaintiff would have emigrated as well, if he were not to wait out the outcome of his complaint.

This citizen`s name is Hansgeprg Hammer and he has a property of 8000 Gulden. I have taken with me a letter from him to a good friend in America, in which he writes that he will emigrate next year. Besides him, many more citizens are willing to emigrate due to the bad governance. One is able to find everything [all complaints] in a protocol that has been sent to the authorities. We are at least 25 citizens, who emigrate because of these reasons. I could tell you a lot more, if only there would be the time for it.”

The commissioner asked, “Why didn`t you complain to the district office?”

“We are put off filing complaints; complainers are held captive in eternity. It is a lost try right from the start.”

And then he asked further, “Why didn`t you complain at the higher authorities?”

“A poor man like me cannot go that far to file a complaint to the high authorities. I am not influential enough for that. The other citizens will lose lots of money through their complaints and they do not know yet, how the matter will end. The costs already amount to over 2000 Gulden.”

The commissioner: “What are the complaints?”

“They are about various sculduggeries of the district mayor and several complaints against the forester and the bailiff.”

The commissioner wrote those words in a book and left. I couldn’t wait to climb onto that barge and get underway, because I was afraid we would not be allowed to leave. Complaining in Germany wasn’t safe!

The Neckar and Rhine

We floated down the Neckar and Rhine rivers on barges towards the sea as the winter ice slowly melted.

We passed villages and castles and more hillside vineyards – sights like we had never seen before.

You’ve seen these sights yourself Granddaughter, those same castles. The Rhine was our highway to America.

The land flattened as we approached Amsterdam and windmills appeared on the horizon.

The vineyards and Germany were behind us and there was no going back now.

Amsterdam

We were supposed to sail for America from Amsterdam on March 30th, but our departure was delayed, first by one thing, and then by another.

Once in Amsterdam, after many false starts, we contracted with a sea captain for passage. The contact for our voyage stated that the captain, 21 sailors and 400 passengers would sail for Philadelphia. By the time everyone was crammed into the ship, more than 565 passengers were on board, with supplies for only 400.

I was proud that I was able to pay our way, although it took every penny and we were packed into the bottom of the ship, Zee Ploeg (Sea Plow), like sausages, all passengers together in a space smaller than our home in Germany. Still, we knew that life would be better once we landed in America so we didn’t mind the discomfort.

We had hope, something that no longer existed in Germany.

Others who immigrated to America earlier had written letters back home describing the bountiful harvests and freedoms there, and we knew that God would deliver us., although he seemed to be testing our will.

But that was all in the past. We were sailing to America now!

Embarking

At first, we were delayed leaving the port of Amsterdam because of bad weather but we were able to live on the ship. Lord knows, there was no money to rent a room. In fact, there was no money left at all.

At last, after a few weeks, on May 25th we departed with one Captain Manzelman at the helm, a man I never trusted. He seemed mean, but we needed him and after all, a ship is a ship. A deal is a deal, and we had already paid.

At long last, we sailed into the sea, but then had to stop for several weeks, a month or more, on the island of Texel near the Netherlands. More foul weather. Perhaps it was an omen, but a man died and had to be buried. Yet another storm was brewing.

We had already used much of our ration of food allotted each person for the journey, and the captain’s mood became sourer and fouler with each passing day. That man is the devil incarnate – mark my words.

We took on more supplies and water in Texel, and a few weeks later, finally set sail again as soon as the winds abated. But it was only the lull before the next storm.

Pummeled by another storm, we had to return to Texel, again. Everyone, passengers and crew alike, avoided the captain who seemed angry that we existed. We felt like he wanted us dead, and truth be known, he did, as we would soon discover.

Finally, finally, on the last day of August we set forth again into the Atlantic, expecting to be in America in just a few weeks.

Our spirits soared!

America, here we come!!!

Forsaken by God

Less than one day into the Atlantic, the wrath of God descended upon us in an angry torrent. A terrible hurricane tossed our ship like a cork in the sea. The massive waves first threw the Zee Ploeg ship skyward into the air, then as we descended into the abyss, crashed over us like deafening thunder. People, passengers and crew alike were drown and swept overboard. Our food was washed into the sea as well, and what wasn’t, was ruined. The water casks crashed through the deck into the passenger hold, below, as did the cannons.

We prayed to the Lord to save us, for food and for fresh water, but day by day, we drifted with none in the unceasing storms. Dying little by little, inch by inch. I can’t even think of that horror. It haunted my waking hours and my dreams until the day I died. I could barely speak of it and Frederica could not.

In the darkest of nights in the worst of gales, we heard a monstrous thunderous crashing, then splintering. The mast twisted, shrieking amidst the squalling of the storm and broke in two, like a mere twig. We knew we were doomed, never expecting to see the light of day. We clutched each other as the water rose in the bowels of the ship and awaited our fate. Frederica hugged the baby to her breast. We held each other as tightly as we could and prayed. We would die as a family.

By some miracle, that ship stayed afloat.

A day or two later, more damage to the ship – the bowsprit snapped too. The sea broke the windows in the ship, and water poured in from every hole.

My God, my God, what have we done to deserve this?

Then, our young Elizabeth, just four and a half years old, died. Wet and ice cold, we huddled together for warmth below deck, starving – with no food or water. The stench of death and sewage enveloped us. We no longer knew whether to pray for life or death. Death seemed more humane.

To make matters worse, the captain tried to poison what little food we had. The men, starving or not, well, we had to take matters into our own hands. We were a captainless, rudderless mass of starving humanity adrift on the angry sea. Completely forsaken or at least forgotten by God. Why? Why?

Oh God, why?

A couple weeks later, we drifted by the Faroe Islands and tried to gain their attention with a shot, but that was not to be and we drifted on, devoid of all hope, starving and utterly forlorn.

Death became our constant companion.

Two Months Later – Norway

At the end of September, after being adrift for nearly two months – I don’t rightly recall the day as they all ran together by then, we thankfully, thankfully, shipwrecked into the shore of Norway near an island called Herdla.

You know the place. I saw you there today, standing at the monument honoring the passengers on the Zee Ploeg.

Lakes, salt, sun, universe, eternity and heaven – the symbols on the monument..

I was with you Granddaughter, as you came back to see me. My heart swelled with pride.

See the islands behind you – that’s where the Zee Ploeg came to rest, rocking back and forth, teetering precariously on the rocky island near the Skjellanger lighthouse.

“Please God, we beseech of you, do not let us break free and wash out to sea again.”

We gave thanks because we were sure that the people ashore would help us as soon as they could see us through the fog. In the name of all humanity, how could they ignore or refuse our great suffering?

Herdla was a small island, maybe a mile long and a quarter or half a mile wide. Fishermen in boats kindly brought us food, but the sight of the dead and nearly-dead on the death-ship, reaching out, screaming in an unknown language and desperately begging frightened the local people. We must have appeared mad, and indeed, we were crazed with hunger and thirst.

They didn’t know what to do with us, whether we were just starving or also carrying some plague that would kill them too. There were so many dead. Some we buried at sea as we could, but when the sea was too rough, our dead family members simply remained with us below deck amid the stench.

Perhaps the people on Herdla wondered if we were even of this world. We looked like the walking dead.

They were kind enough to allow us to bury some of our deceased in the churchyard. I hope they said prayers over their bodies and for the souls of our relatives.

We were dying every day now. Entire families perishing, one by one.

The wailing never stopped. The screams and moans of unimaginable night terrors, except it was real and there was no escape. The only escape was death itself.

Bergen

The men in Herdla sent an emergency message to Bergen, the capital of Norway, further down the fjord. What were they to do with a ship full of starving, sick castaways?

We didn’t know anything about Norway. In fact, we weren’t supposed to be anyplace close to Norway. Driven by the storm, after the mast and bowsprit broke, we could neither navigate nor control the ship, nor did we know exactly where we were.

Fortunately for us, the Norwegian people, at least near the sea, were at least somewhat familiar with Germans. Hanseatic League German merchants had been trading with Norwegians for hundreds of years. A few people spoke a little German and all people living by the sea understood a shipwreck and hunger.

Norway itself was struggling. The country had been gifted to the Swedes by the Danes just three years before, and many of the bureaucrats in charge had little experience.

We were devastated, crushed, when they decided that we could not remain in Herdla and in fact, we could not come ashore at all. It appeared that our incredible relief at being washed up on the island and being discovered was premature.

Overwrought, we were trapped on the ship in our misery which deepened day by day.

Elsesro

The Zee Ploeg was towed to a shipyard north of Bergen, called Elsesro, where we were quarantined on the ship in this bay, right beside the buildings with the red roofs, for 30 days.

This is how Elsesro looked in 1814. It’s still recognizable today – even the red roof buildings

I stood beside you as you stood witness at Elsesro overlooking the sea, where the Zee Ploeg was tied, feeling our sadness across two centuries. Palpable, you can still touch our grief, and through it, you touch us.

The disabled Zee Ploeg was tethered to the dock beside one of those warehouses with the red tile roofs, just beneath you Granddaughter. Perhaps, if I could have peered up into the future, I could have seen you perched upon that hill, reaching out to me through the mists of time.

I was with you in Elsesro today, my Granddaughter.

You stood where we stood, where our children played and we heard their laughter once again as the sun grew warm. You touched the trees that were saplings when I staggered upon that land, falling upon the ground in thanksgiving after emerging from that hell-hole ship, reeking of death.

You stood just a few feet away.

Ahh, some of those sturdy trees are gone now, as am I, but the stump remains, just as part of me remains in you.

Purgatory

We hoped that our fate had turned for the better at Elsesro, but we questioned if it could be so. We didn’t know the language and wondered what would become of us. America was never further away. Germany was in the past. We were in limbo. Purgatory on Earth.

While incredibly relieved to no longer be adrift, we looked out at this bay for 30 long days, wondering if we would leave before that time, feet first.

Death seemed to be the only way off of this terrible ship.

God, it seems, wasn’t yet done testing our will.

Those 30 days and nights were endless, relentless. Still, more people died. And more. And more.

When that eternity had passed, we were allowed to depart the ship. We had no place to go, we still had no food, our clothes were in tatters and as the local residents described us, we “were more dead than alive.” Begging was against the law, but what choice did we have?

Thank God, some of the residents at least took the pitiful wailing orphans into their homes, hearts and families.

You met one of their descendants today, Granddaughter, Christian Rieber. He built that lovely memorial for the Zee Ploeg survivors in Herdla where we stood together.

Christian’s ancestors died on the Zee Ploeg and we tried to comfort the orphans, but could not.

The Zee Ploeg was so badly damaged that she could not be repaired. The breaking masts had crashed through the deck and broken the sides.

Not knowing what to do with us, the Norwegians are a resourceful lot.

At Elsesro, another ship with no masts called the Noah’s Ark was tethered to the Zee Ploeg, upon her deck. Those of us left alive lived between the two ships lashed together in the cove, cold, miserable and suffering as the gloom of winter fell upon us.

Still, it was better than dying one by one, adrift at sea.

The Noah’s Ark Tragedy

Elsesro, where you stood today, was where the tragedy of the Noah’s Ark took place, as if there hadn’t been enough tragedy already. More terror and death.

In January, on the 14th, in the dead of the winter during yet another horrific storm that blew in from the north, the Noah’s Ark broke loose from the Zee Ploeg, crashing into the sea and drowning many of the people who had already survived a shipwreck and starvation, sweeping them out to sea. Then another 20 died in the next fortnight from terror.

The survivors, nearly drown, became very ill. Today, you might call it pneumonia or maybe they had heart attacks, but we didn’t know why back then. Slowly, more died and were buried in the churchyard behind St. Mary’s Church, the church in the neighborhood where the Hanseatic League Germans lived.

Thank goodness those Germans spoke our language and we could at least have the comfort of a funeral service we understood to bury our unfortunate dead. They wrote the names of our dead in their church book, giving us at least some semblance of normalcy and consolation.

Those we had to bury at sea had nothing more than a prayer, and those swept overboard…I can’t bear to think…

22 Kong Oscar’s Gate

You probably didn’t know there were hospitals in 1817, but one, of a sort, existed in Bergen, left over from the war with Sweden three years earlier where captive soldiers needed treatment. That’s where the desperately ill were sent, often to await the grim reaper. 22 Kong Oscar’s Gate, meaning house 22 on King Oscar’s Street.

The building that served as our hospital isn’t there anymore, of course, but I walked beside you when you climbed the cobblestone street, the same one I trod, and visited the building in that location today to see where we lived.

I was fortunate, if you can even use that word to describe our plight, that most of our family was in the hospital and had been since October. They had to carry us off of that ship. We couldn’t walk and were very nearly dead. So I wasn’t on the Zee Ploeg on January 14th when the Noah’s Ark accident happened.

More than 100 people had died by this time, including all 30 babies born during the journey. We no longer knew who was still alive. Confusion reigned.

After the Noah’s Ark accident, many more were sent to the hospital to recover, or die. Twenty more died that next week. There were funerals every day. Graves couldn’t be dug fast enough.

Thankfully, kindly townspeople brought us food, and clothes, for we had none.

The Lawsuit

I know the Bible teaches us forgiveness, but I could not forgive that despicable captain for what he had done to us. Manzelmann, of course, had secreted food away and he didn’t suffer the same fate as we did. Then, he tried to poison us. He was seen acting suspiciously and slipping poison into the kettle of gruel.

Some of the ruined food was saved and indeed, it proved exactly as we suspected – POISON. We should have made him eat it. We had to dispose of that poisoned food, meaning what little food we had was wasted as we starved. His murderous intentions and incompetence in so many ways caused the terror, torture and deaths of our countrymen and cousins. He didn’t care.

In essence, he killed our beloved daughter, Elizabeth. No, I could not forgive that man.

By January 8th, I was once again able to walk, so Johann Fidler and I filed suit against Captain Manzelmann, asking for our passage money to be refunded so that we could pay our Norwegian benefactors and once again purchase passage to America.

Manzelmann claimed that he was not responsible for our predicament, that we needed to sue the company in the Netherlands that we contracted through for his services. Under the dark of night, Manzelmann stole board a ship and returned to the Netherlands, leaving the misery and devastation he caused behind, never having to answer for his actions. We should have hung him on the ship when we had the opportunity.

The Zee Ploeg was too badly damaged to be repaired or rebuilt and her wood became part of those warehouses you saw at Elsesro today, Granddaughter. Who knows, maybe part of her still remains in those rafters.

New Beginnings – A Wedding and a Baby

On February 8th, my wife Frederica’s brother, Johann George Ruhle, married Catharina Koch, a girl from Schnait who was also emigrating. Her mother was a Ruhle, related to my wife, and her grandmother was a Lenz, related to me. Actually, in those two villages, there wasn’t anyone who wasn’t related, several times over.

George and Catharina courted while we floated down the Rhine past those majestic castles and after we climbed aboard the Zee Ploeg in Amsterdam.

Those castles were a romantic sight alright and enough to inspire anyone. In June, they announced their engagement, although we certainly suspected. They would marry after we arrived in America. We all celebrated and well, they might have celebrated a bit too much.

Georg and Catharina married in Bergen in the old Cross Church, just around the corner from the hospital where we had all been taken. The door was always open then too.

I walked beside you in the church today, my Granddaughter. The inside looks much the same as it did when we fervently prayed for safe deliverance.

We sat in these pews and prayed at this alter, day by day, to God to deliver us to America. With no resources, we were entirely at his mercy.

Was there a way for us? Was there any salvation on this side of the grave? How many more would die? I would rather die than go on alone.

I know it sounds odd to say that we were fortunate to be so ill, but the hospital is what saved us. We weren’t on board when the Noah’s Ark broke free, plummeting into the sea.

The hospital was barren and stark. The townspeople of Bergen brought us food and a few clothes. We were so grateful because, austere as it was, it was so much better than the ship. Somehow, we had been transformed from hopeful emigrants to pathetic beggarly refugees.

As we could, we wove and repaired fish nets and anything else we could do, but we were far more of a burden to the people of Bergen than anything else. They too had suffered at the hands of Mother Nature, with starvation knocking at their doors as well. They had little to share, but shared what little they had.

Not to mention that having been defeated in the Napoleonic Wars, they had been overcome by Sweden just three years before. They were terribly poor, just eeking by. Thank God for the blessings of the bounty of the sea, or we would surely have perished altogether.

A Secret

Let me tell you a little secret. No one can hear, can then?

Frederica’s brother’s wife, Catharina, when they married in Bergen, was “with child.”

Shhh….

There was no way for Georg and Catharina to marry on the ship, and although they were properly penitent for their immoral behavior, celebrating their upcoming marriage prematurely one would say, it was too late. A child, we thought, would brighten all of our spirits. This child seemed ordained by God, especially since the baby was born in February, even though his mother was starved during her pregnancy. We gave her as much of our food as we could.

Little Joseph Ruhle was born at the hospital on February 28th. We rejoiced and baptized him right away right around the corner at Cross Church, where his parents were married.

We were so thankful to have a place to worship so close by, less than a block away, around the corner just past the green house.

I proudly carried little Joseph to the church myself as his mother rested! He was the newfound joy in our life. The symbol of our hope for our new lives.

I saw you lovingly touch that baptismal font inside the church today, Granddaughter. We gathered around that font as baby Joseph Ruhle was baptized. We were so grateful to hear him cry, full of life, despite the odds. That day seemed to be the turning point. Frederica’s father, Adam, the baby’s grandfather proudly served as his godfather. Joseph’s birth gave us all renewed hope. Yes, life was improving now!

Things were looking up.

But Baby Joseph too was soon cruelly ripped from us, exactly three months later in May of 1818. We sorrowfully wrapped his tiny body for burial and said our goodbyes. The funeral was held the next day, on May 28th in St. Mary’s Church with a German service, his little body laid to rest in the pauper’s corner, beside the rest of the Germans from the Zee Ploeg who had perished.

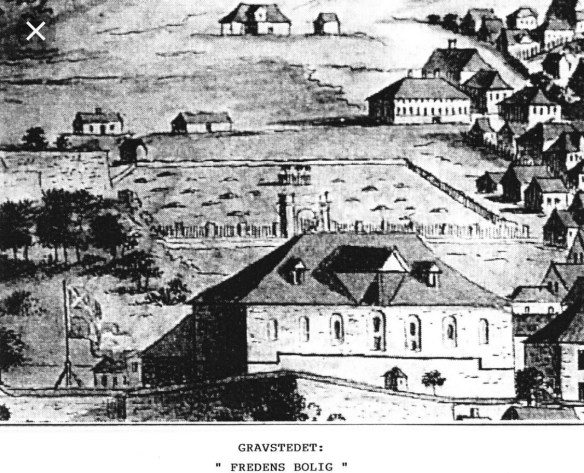

More than 2200 people were buried in that field above the church. It’s a Park now, still known as “The Grave.”

Most of the graves weren’t marked then, and all are gone now.

I saw you here too, Granddaughter, searching for his lonely grave in the rain today.

None of us could afford a stone. No one knows now where his little body was left behind, his grave lost to history forever.

We washed you with our raindrop tears, but do not grieve, we are with him now.

The Rappites

After baby Joseph died, our despair seemed to deepen with every new day. We knew that we could not stay in Bergen forever. The Norwegians didn’t want us, and we couldn’t blame them. We didn’t want to live as paupers, taking charity. We couldn’t support ourselves. We still needed to find a way to America, but there were very few options.

Frederica’s half-brother, Christian Breuning managed to arrange passage for himself on a ship for America in July. The Rappites from the Harmony settlement in Indiana were willing to pay the passage for anyone who would join their colony, but of course their way of life was very strict and included complete celibacy. Being a young father, I didn’t feel that was the right answer for our family. Lucky for you, Granddaughter, because your mother’s grandmother, our daughter Margaret wasn’t born until the last day of December in 1822, the day before our 3rd anniversary setting foot on American soil. If we had joined the Rappites, well, to put it daintily, you wouldn’t be here.

Christian Breuning left Bergen on August 13th on a ship that held 80 Rappites, although we understand that the Rappites later felt the German boys were too rowdy for their settlement. Some passengers disappeared after arriving in America and never made it to the Harmony settlement, apparently having a change of heart. We always wondered what happened to Christian.

After Christian departed, our countrymen continued to die. Three of our cousins from Schnait named Daniel Lenz died and are all buried with the others in the poor section in Fredens Bolig Cemetery, above St. Mary’s Church. Conrad Lenz died too. One grief on top of another.

The Ship Prima

The Norwegian grey skies and never-ending winter rains had begun, the sun disappeared for days at a time, and darkness was descending on the country.

The people of Bergen were as desperate to be rid of us as we were to be gone. We could not return to Germany without money, as the king made it very clear when we left that we would never be allowed to return. Germany didn’t need any more poor people and the Rhine was in essence a one way river. Our families there were all in desperate straits as well, with the crop failures and high taxes and could not sponsor our return.

Finally in the late fall, the Norwegian government found the captain of the ship Prima who agreed to transport us to America and allow us to be sold into indentured servitude after arrival in order to pay our passage. Indentured servitude would take another 7 years. Surely Frederica’s parents, Adam and Katharina Ruhle would never live that long. She would be 70 and he would be 61 by then. Who would even purchase them? Indeed, 11 people on the ship were too old to be sold after we arrived in America.

This was Captain Manzelmann’s fault – that evil, despicable man. He had brought this disaster upon our heads. Passage to America should not cost us another 7 years, 7 very long dear years of our lives. It has already cost us one and a half years, and we were destitute refugees in Bergan, not near America yet.

By the time we sailed to America, were auctioned and served 7 years, it would be nearly 10 years since we left Germany, hoping to start a new life. Adam and Katharina’s life would be over. They would have sacrificed and suffered for nothing.

I had paid the first passage for the entire family, but without a penny to my name, we were reduced to charity and utter dependence in Norway. Our sole request was that we would be sold together as a family. With that agreement 270 Germans, us included, climbed aboard the ship Prima and set forth again.

Frederica cried as we boarded the Prima. Terror was in our hearts. Our unsteady legs shook, but we had to climb aboard that ship.

Our child’s body along with so many of our countrymen already rested beneath the sea with more left behind in St. Mary’s churchyard. Of the almost 600 people that sailed on the Zee Ploeg from Amsterdam, only about 350 left Bergen. That doesn’t count the newborns who perished of course, and it doesn’t count the few orphans who survived and stayed behind in Bergen with their new families either.

The first few weeks on board the Prima were almost normal, as voyages go. Captain Woxland chose the southern route due to the lateness of our sailing. Along the coast of Portugal, we caught the never-failing trade winds and sailed across the sea to the West Indies. We heaved a collective sigh of relief, but once again, the unholy seas turned on us.

Captain Woxland had to fight a raging storm, a hurricane that nearly caused our ship to capsize. Terror filled our hearts once again, but Woxland was a skillful Captain and a good man, not at all like Manzelmann.

To help quench our fear, we prayed aloud and sang songs. The Lord had brought us this far and surely, surely, He would not let us perish now. We did not arrive in the fall as planned, and not in Philadelphia as we intended, but weeks later limped into Baltimore midwinter, on New Year’s Day 1819. We had been delivered. We had escaped the dragons of the sea for the sixth time. Thanks be to God.

Of course, we were yet to be sold, auctioned, but we would never have to set foot on another ship, nor would we, for the rest of our lives. Nor would our descendants for five generations, until you, that is. I don’t know, my dear, if you are brave or foolhearty! But you are assuredly one or the other.

Your Return

Granddaughter, I’m so glad you returned in the ship in the sky. I hope you can feel my love and gratitude across the years.

I’m so thankful that you made your way back to look out over the fjord to the island across from Herdla. Never was anyone so glad to be cast upon rocks!

The simple church on the hillside there gave us such hope as we saw the boats approaching from the shore with food. We rejoiced, watching the arrival of our saviors.

I’m so grateful that you returned to give thanks in the church in Herdla for the people who saved us. They’re buried in that churchyard by the sea, you know. We owe those good people our life, and yours.

It’s fitting that a replica of the Zee Ploeg graces that church today, commissioned by Christian Rieber, a fourth generation descendant of one of those pitiful orphans. Our descendants sure have done us proud.

I’m sure you know of the Norwegian custom of building a replica of a shipwrecked ship and donating it to the first church the survivors worshipped in to give thanks to the Lord Almighty for their rescue. See the Zee Ploeg hanging there from the rafters? Now you know why.

You walked in our footsteps in Elsesro too. A place of great relief and also of great sorrow.

So much to bear, when life was already unbearable. Elsesro’s peaceful beauty today belies the tragedy tucked away beneath years of forgetfulness.

The hospital, our place of salvation and our makeshift home for so many months is gone now, but you visited us there too. Our spirit remains. We trod those same ancient cobblestones as we walked up and down the hills streets of Bergen, and around the corner to the Cross Church.

By Thomasg74 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0 no, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21771343

I saw you at the church door today, exactly where we stood too. We passed through that very door.

I was so touched that you walked up the aisle in the Cross Church were Frederica’s brother was married and baby Joseph was baptized with his grandfather standing proudly beside the baptismal font. That was one of our few days of happiness and joy in Bergen.

Bless you for your prayers for our souls there. We pray for yours as well.

The Cross Church provided us with peaceful respite then, just as it did you today.

Sermons at St. Mary’s Church were in German, a comfort to us, and Lord knows, we walked up the streets to that church for another funeral every week, it seems. Sometimes every day.

By No machine-readable author provided. Mortendreier assumed (based on copyright claims). – No machine-readable source provided. Own work assumed (based on copyright claims)., CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=979904

We stood in St. Mary’s Church beside you today, just as we stood there the day we buried baby Joseph, and Daniel Lenz, all three of them, and Conrad Lenz and so many more.

The tiny bones in the cemetery on the hill behind St. Mary’s Church are long returned to dust. You did what we could not do, standing in our stead at the grave of that sweet baby boy and others that we left behind in that pauper’s field.

The burying ground is a park now, but we walked that sacred land with you. Our dust still remains.

Our memory lives again. We became you. You carry us in your veins. Remember, our and your DNA rests in the Bergen cemetery too, beneath the sea, and in churchyards in Germany, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana.

Frederica’s parents, Dorothea Katharina and Johann Adam Ruhle never made it to Ohio with us to see our new land. We lost them along the way.

Thank you, Granddaughter for rescuing us from the death ship of oblivion. For finding us and telling our story of that tortuous journey. The wonderful people of Bergen saved us then, and you saved us again. As long as someone remembers us, knows our story, we aren’t entirely dead. Well, we may be dead, but we aren’t gone and forgotten.

If you doubt that I was with you today, look upon this rainbow across the harbor at Elsesro, a gift from me and your ancestors already here – your mother too! We struggled to help you find your way to Norway and we are smiling, ear to ear!

You made it!! We never doubted your resolve. After all, you carry our blood.

The rainbow begins, or ends, in Elsesro, in the shipyard – just like it begins and ends with you. Indeed, Elsesro is the pot at the end of the rainbow, on the left end of the faint double rainbow, the beginning of the next generation.

Need God speak louder?

You, Granddaughter, are our pot of gold – although you think that we are yours.

Yes, that journey was terrifying, devastating and our hearts still ache, but it was the path to you. We did survive and live on through you. You make us proud!

Know that as we watched you sail away on a very different ship, we stood on the mountain top watching over you. As we will, Granddaughter, all the days of your life.

Grateful acknowledgements:

Many people played a part in in bringing the life of Jacob Lentz, his wife Frederica Ruhle, her parents, Johann Adam Ruhle and Dorothea Katharina Wolfin, and Frederica’s siblings together in Germany, then in Bergen, and finally in the US. I am eternally indebted to the following people who helped me along this path in so many different ways with rescuing these ancestors, and their story, from oblivion.

- Christian Rieber – Benefactor for many Zee Ploeg descendant historical contributions including the monument and pavilion being built nearby and the museum documentary. Christian is an inspiration for all generations.

- Sigmund Steinsbo – Our gracious host on our Herdla day – thank you so much for driving.

- Arnfrid Dommersnæs Mæland – Bergen historian extraordinaire who served as a wonderful liaison in Bergen. I couldn’t have had this amazing Bergen experience without Arnfrid. Most of the historical images and some of the contemporary photos are courtesy of Arnfrid.

- Arvid Harms – Arnfrid’s husband, wonderful, patient and amazingly unique companion (who drives a very cool Bentley).

- Arne Solli – Bergen historian and researcher.

- Herdla Church – Steward of the Zee Ploeg ship replica.

- Herdla church historian – Generously provided access to church and prepared a historical presentation.

Herdla Church visit, left to right, Arvid Harms, Arnfrid Dommersnæs Mæland, church historian, me, Sigmund Steinsbo

- Herdla Museum and staff – Welcoming guardians of the Zee Ploeg video (in both Norwegian and English) that resides in the museum. The Zee Ploeg monument and pavilion are also located on this lovely property.

- Gunnar Furre – Herdla Museum Director who hosted our visit and tolerates Zee Ploeg descendants who return like homing pigeons.

- Yngve Nedrebø – Historian at the Bergen archives.

- Håakon Andersen – Amazingly talented creator of the Zee Ploeg ship model.

- Liv Stromme – Assistance with Zee Ploeg research.

- Lisbeth Lochen – Assistance with Zee Ploeg research.

- Martin Goll – Assistance with Beutelsbach and Schnait research.

- Niclas Witt – Assistance with German archival material and retrieval.

- Jim – My husband who accompanies me on any number of insane adventures and claims to like it:)

Wonderful traditional Norwegian dinner in Bergen with Arnfrid, Arvid, me and Jim. The perfect evening. Jacob Lentz may have been there too, but if so, he didn’t eat much nor drink any of the local brew.

Researchers wishing to remain anonymous:

- Tom – My cousin, retired professional German genealogist and research partner, whom I adore for many reasons.

- Chris – Native German speaker, my friend who loves history, is eternally curious, finds the most amazing resources and rounds out our research team perfectly. I met Chris on this trip too, but that’s a story for another time.

Without the consistent combined efforts of Tom and Chris, Frederica Ruhle would never have been identified, which ultimately led me to Beutelsbach, Schnait and then Bergen in person. None of this would have happened without them. These men have never-ending patience and there isn’t a big enough thank you.

I am amazed, over and over again how, through genealogy, we meet complete strangers and emerge fast friends. For that gift, I guess I have to thank Jacob Lentz.

Footnotes:

The interviews by Friedrich List were extracted from the book by Günter Moltmann 1979, “Aufbruch nach Amerika. Die Auswanderungswelle von 1816/17,” and translated by Chris.

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- Family Tree DNA

- MyHeritage DNA only

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload

- AncestryDNA

- 23andMe Ancestry

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists for genealogy research

Discover more from DNAeXplained - Genetic Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I read the whole story though it soon became difficult to read through the tears. I wonder how difficult the travel to America was for my Swedish ancestors who came to America in the 1800s to settle in Minnesota. I doubt that they had nearly the hardships that your family had. It was a large family but I think that they all arrived in Minnesota and settled there and married and worshiped and lived on and their descendants are there still yet I have not met any of them. It was only recently that I discovered them so I do not know the story of the immigrants. Thank you for the telling of this story of great hardship. It is the story of many immigrants even those who arrive today, a story of strength and perseverance.

There were times when I was researching this that I had to stop. It was gut wrenching. I’ll be publishing the actual story of the ship and passengers separately.

I will keep an eye out for it! I have spent hours reading her blog today and so many things in my tree have come together, you have brought our ancestors alive for me. Thank you! So glad I reached out to you. So many never respond to me, I was adopted, it didn’t work out so spent much of my childhood in state custody, so all of this means the world to me!

Oh wonderful! I have been trying to find out more about the Lentz in my tree and when I introduced myself to you this morning I had NO CLUE that you were a connection to them, then you posted this this evening!!! I was just talking to a friend and possible cousin day before yesterday about this! Right on! Synchronicity!!!!

Maybe they’re speaking to you too!!😁

I will keep an eye out for it! I have spent hours reading her blog today and so many things in my tree have come together, you have brought our ancestors alive for me. Thank you! So glad I reached out to you. So many never respond to me, I was adopted, it didn’t work out so spent much of my childhood in state custody, so all of this means the world to me!

Wow Roberta and an enormous vote of thanks & gratitude to the forebers of Jacob Lentz

Wow! Just wow! Thank you for sharing the story of this incredible journey with such beautiful words.

What a wonderfully written heart-wrenching story! It brought tears to my eyes.

On a scientific note, I recently encountered an article about the fate of the Dunbar prisoners in the Durham cathedral. One of the theories about the deaths of the prisoners is that they suffered from the “refeeding syndrome.” When people starve for a long period of time, they need to be refed a certain way, otherwise they can die. This happened to POWs and Holocaust victims at the end of WWII. It’s not impossible that ignorance may have led the Norwegians to feed these poor survivors far too much right away, with tragic consequences.

That could explain why so many died that first month after their arrival. Thank you for this.

Thanks! I wanted to mention that because I bet that it’s a possibility that genealogists and even historians never even consider when they analyse an event (or series of events) like that.

There may have been other factors at play since the whole of Europe was struggling to one extent or another in the Year Without a Summer. Depending on what they were being fed, scurvy might also have been a problem. Also, their living conditions weren’t even adequate, so they could have died from a lot of things, from the cold to infections in a damaged boat that was bound to be unsanitary at that point. Maybe someone competent published a medical article about that in Norwegian, at some point. That would be interesting.

Thank you, Roberta. That was just Lovely and speaks to my own passion of recovering the memories of my own ancestors and walking the same paths that they too once walked. Such a blessed story and proof that some of us are here only through the mercy of God that was bestowed upon our ancestors.

Kind of chilling to realize how close we all came to not being here.

Thank you, Roberta, for a most eloquent reminder of why we genealogists do what we do. And for inspiring us to study the lives and history of our forbears, not just record dates and places.

Those dates are just brackets. And hints:)

Wow, what a story. What a beautiful tribute . You are amazing!

Thank you but all of the credit goes to the amazing people who helped me. Wouldn’t have happened otherwise.

Hi Roberta

My email gets a lot of stuff from this address so I do not read most, as they contain too much information for my skill level in this field. However, I did just read your story of your grandfather in Norway, or great-grandfather. Good story and impressive sleuthing. However, if I look on my ancestry.com tree, I cannot imagine how anyone could have the time to discover all the stories of the myriad people who have gone into one’s making over the last 400 years. Considering what you had to do just for one story.

And particularly in light of the chromosome painting article just below the story, which looks like a tremendous amount of work. I did not read your articles on painting because I am not sure what I would do with that information. I think my skills are too rudimentary at this point. Nor do I see how that could help me with my brick wall. The story about your father is too wild to follow. I could not imagine wading into that tangled skein and trying to tease out the truth.

But compliments on the shipwreck story. I can only hope that my German and Dutch forebears did not endure the same type of voyage. All I know is what most Americans know: somehow, some of them got here:). All those Dutch and German names from the 1600s and 1700s–pretty much filling the ranks of so many branches back then, but replaced by English and Irish names as they get closer to me. That is why the DNA seems so important, because it always tells the truth, and as your story about your aunt and father shows, it is hard to rely on memory. Since I got interested in the DNA and the tree stuff, many people I know, while curious about Neanderthal, are mystified as to why I would care who came before me. I cannot really answer that.

Cheers, Cynthia Royce

Sent from my iPad

>

Gave me some background on why my gggrandfather and mother may have left Wurttenberg. I have a copy of his naturalization paper, which doesn’t match the port of landing, and his name is not in the Wurttenberg emigration list for that decade. Searching on. Thanks for giving me hope to finding him sometime.

Some of the records I need just aren’t there either. Keep up the good fight. 😁

Roberta, of all the family Archivists out there today, YOU are the GREATEST!!

Whatever repository receives your legacy of historical works will be most fortunate! Your ancestors come to life through you and they will be remembered down the ages.

You are leaving an important historical legacy.

Years ago you had not decided where you would place your work. Have you decided? A state archives would be great; but which state? National Archives?

No, I am still struggling with that. I don’t really think any of them would want them. And I don’t know what will happen to my blog when I die. I have contributed much to the Allen County Public Library already. Maybe eventually I need to print and bind these so they can be donated in a more traditional fashion.

As a French Canadian with (Dover) Quakers in my ancestry, I am wondering why there is nowhere you can place that precious research, which you have been conducting for decades, in the United States. The Quaker libraries have preserved personal items like family bibles… These archives are therefore organized under the umbrella of the family’s Church.

In French Canada (Quebec), we have preserved the research of top genealogists in what the call the National Archives (the provincial library). They are in their own collection that bears their name. Some of these collections are very big, and done before the times of computers. These become great resources for future generations. Many more people must be related to you than you can imagine, and they could all benefit from accessing that research, now and in the future.

You’re pretty famous genealogist, aren’t you? Would they take those archives/databases at the state library? That’s what we do (in crazy Quebec). We also have family associations for certain surnames that publishes relevant articles in their periodicals. Don’t you have lineage societies and genealogical societies that have the preservation of such records and research in their mission statement? What’s a few generations back today will be remote ancestry at some point in the future, and some of your research, as in this particular case, touches major events in history that are mentioned in history books. That’s pretty relevant.

I love the way you wrote this story of your family. It was a pleasure to follow the journey.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. Thank you.

Fantastic story…is there an ending?

On Sat, Oct 6, 2018, 22:00 DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy wrote:

> Roberta Estes posted: “Granddaughter, can you feel me beside you here > today? Can you sense my presence? Can you hear me as I tell you my story > about the death ship – the Zee Ploeg? Have you come back for me? Bless you, > child. Listen. Listen… You can hear ” >

Yes. Ironically, I’ve already written those stories. In the article, his name is linked early on. There are two earlier articles. In the first one I didn’t yet know about this part. You can also enter the word Lentz into the blog search box. Glad you liked the story enough to read more. Fredericka’s story is there too, along with Adam Rühle. I have finished Dorothea’s yet.

This was a beautiful piece of writing, Roberta. I stood beside you, behind you, with you, everywhere you looked.

Brilliant telling of a harrowing story. I found it riveting and although I knew from the start that it was going to be very sad, I knew that they had made it westwards eventually.

This is awesome! I have been helping a friend discover her bio father’s ancestry (and identity). We have her father’s family back to Jacob Lance Lentz (1797-1873 buried Decatur, Iowa) and Fredericka Vogt Lentz (1770-1828). She has a DNA match for Ruhle, Cindy Buhs, that is descended from Jacob and Fredericka Ruhle! My friend is going to be so excited! I just saw this so I have not had time to put it together any better than this, but this is truly wonderful! Thank you SO MUCH! Phyllis LewellenArizona

Hmmm, this is interesting. Does she have a Y DNA tester from the Lentz line?

Thank you so much for sharing! Hannah Joan Lentz was my fourth great grandmother b. 1785 in North Carolina.

Thanks again!

1816 was a terrible year. See “Volcano Weather: The Story of 1816, the Year Without a Summer” by Henry Stommel. All caused by the blowing of Mt Tambora in Indonesia the previous year. It caused mass hunger worldwide.

Besides that, there had been a long period of emigration from that part of Germany because of the wars and economic problems you described. Your story is almost a carbon copy of the “Poor Palatines” who came to Upstate New York a century before, after an unwelcome sojourn in England. Later, Catherine the Great encouraged immigration to south Russia in the early 1800s to farm the rich land she had conquered. Some of your relatives and my wife’s took advantage of that – to their descendants great regret in later Communist times. My wife’s family lived just a few miles from the Lenzs and some came to USA and some to Russia. Your grandfather Lenz and family might just as easily gone to Russia as USA.

In fact, at least one of your relatives did, that same year of 1816/17 , the peak of emigration. See the excellent website odessa3.org with its subpage:

Ostwanderung der Württemberger 1816-1822, Summary (D. Wahl) and its accompanying table pages. It’s oriented to Germans to Russia, of course, but does tally all the emigration at that time. For example, at Lenz’s emigration, twice as many went to Russia as America:

“Emigrants from Wuerttemberg in the years 1817-1820

in order of month and destination

Emigrants to Russia N America Austria Prussia Europe

1817

January to March 8452 5047 2609 576 18 202

Interestingly, in one of its tables it shows:

“Daniel Lenz Winegrower Beutelspach, Schorndorf 58 wife – and 2 sons 22, 14 years, 2 daughters 28, 25 years to Caucasus alt Andreas Becker, Weingaertner [Winedresser] from Beutelspach”

Same year, same town, same name. His uncle & cousins, maybe?

Completely unrelated, but does the comment thread on your DNA ethnicity article break all records for number of comments? Do you get paid by the comment? 😉

I wish I got paid at all.

Just noticed, from that same website:

Lenz, Jakob Lenz jung Beutelsbach Schorndorf [Applied} 19 Mar 1817 [Approved] 28 Mar 1817

So I assume that’s his emigration permission, not necessarily to Russia. Does jung mean Junior?

Means younger but not necessarily “junior” as we think of it.

Beautifully written, Roberta. I had chills. It really was as if you felt your ancestor speaking to you!

The Jacob and Fredericka discoveries over the past 2 years have been joyous, amazing and remarkable. Beginning with the “Ruhle not Mosselman” discovery and leading to the Zee Ploug/Prima revelations, wonderful new adventures have developed for which I am most excited and truly grateful. Your efforts in writing the amazing story is most helpful in interpreting all the information in a delightful way. All this makes me proud to be a Lentz! I do enjoy vicariously travelling with you to these significant sites. Thank you for taking me with you!! Sincerely, Keith Lentz La Verne CA (Great, Great Grandson of Jacob and Fredericka.)

Their story is one way to bring the cousins together, even if it is electronically. So glad you’re enjoying.

Roberta, I can not even start to tell you , how much I enjoyed your story. I can only imagine that my husband’s Burger family from Germany may have endured some of the same fates. I appreciate you sharing, as most of us will never be able to obtain so many facts.

I never dreamed that I would be able to. I think if the voyage had been more normal, there would have been no, or much fewer, records.

Such an incredible story, told in a way that put me right there with them on that ship.

Your family is truly blessed to have you chronicling their history and helping their ancestors to live even today.

Hi from Bergen, Norway. I haven’t read everything yet, but I will. It’s written in a beautiful way. 🙂

I know the De Zee Ploeg-story well, and have recently visited Herdla to see the place.

The story about De Zee Ploeg will be set up as a play at the theatre here in Bergen next year. I look forward to it.

https://www.bt.no/kultur/i/P38Gpz/Rieber-familiens-tragedie-blir-storslatt-teater-pa-DNS

Do you live there? I may well come back for the play.

This was so very beautiful. Brought me to tears

Pingback: How to Use a Website to Tell Your Genealogy Story ~ Word Quilt

It’s very cool to discover that WordPress used your blog as an example (a good example too.) 🙂

Pingback: Almost Dying Changes You – 52 Ancestors #348 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy