The 1684 Miesau, Germany marriage record of Johann Michael Muller, widower, to Irene Liesabetha Heitz identified him as, “Michael Müller, legitimate son of the deceased Heinsmann Müller, resident of Schwartz Matt in the Bern area.” Of course, Bern is in Switzerland.

Thank goodness for the location and name of Michael’s father, because without those tidbits, we would never have found that information and Michael would have been our dead end.

Schwarzenmatt, Switzerland

My trusty friends Chris and Tom drilled down on the available information to determine what could be discovered. Chris says:

“Schwarzmatt” is/was part of the church books of Boltigen.

The Boltigen church books are online here among the Bern area church books:

So it should be possible to verify if there was a Michael Müller, son of a Heinsmann Müller in Schwarzmatt.

Heinsmann is a very unusual name. My friend Chris has been researching the Boltigen Muller family on my behalf and he contacted Konstantin Huber who had searched for the Millers from that area years ago. Konstantin didn’t have additional information about the Boltigen family but did state that “Heinsmann” is a rare, old-fashioned form of “Heinrich” that he has never seen before in the 16th/17th century church books from Switzerland. Hence, he suggests that the original name of Michael Müller`s father in Switzerland may have been “Heinrich” and was maybe changed to or simply recorded as “Heinsmann” in the German Palatinate. Chris believes that with Konstantin`s decades of experience on Swiss emigration to Germany that this is a valid suggestion, and I agree.

Chris continues:

I also found that a daughter of a Müller from Boltigen married in Dudweiler, Sulzbach, Saarland, Germany:

“Am 03.05.1718 wird Anna Magdalena Müller, Tochter des …. Müller aus Boltigen im oberen Simmental, Kanton Bern in der Schweiz, dem Johann Jakob Blatter, Sohn von Michael Blatter und Maria Mögel auf Neuweiler Hof, angetraut.”

On the page http://www.rolf-freytag.de/fhilfe/schweizer.html about Swiss immigrants in Saarland, you will find this in the first half of the page (and a few records below a Hans Stutzmann in Völklingen).

Chris subsequently discovered another document discussing the Muller family in Schwarzenmatt.

In the description of the old house in Schwarzenmatt it is stated on the first page:

“Vor 1615 gab es im Dorf Schwarzenmatt nur wenige Hofstätten. Mit Sicherheit lassen sich bloss deren vier nachweisen, dazu gehörte auch das Haus auf der Kreuzgasse. Wie Eintragungen in den Kirchenbüchern zeigen, besass stets die gleiche Familie Müller dieses Haus, mindestens seit 1700; im Jahr 1872 verkaufte aber David Müller den ganzen Besitz seinem «Tochtermann» Friedrich Bhend, der 1868 von Unterseen nach Schwarzenmatt geheiratet hatte.”

Translated to: “Prior to 1615 there were only few houses in the village Schwarzenmatt. We can only safely verify four, among them the house in the Kreuzgasse. As records in the church books show, this house was always owned by the same family Müller, at least since 1700; but in the year 1872 David Müller sold the entire property to his son-in-law Friedrich Bhendd, who, coming from Unterseen, married to Schwarzenmatt in 1868.”

I am aware this is very weak evidence to assume a relationship to the Michael Müller family, but at the very least it goes to show that a Müller family was among the first in the village Schwarzenmatt.

If Heinsmann/Heinrich is identified as Johann Michael Muller’s father in 1684, and Michael was born in 1655, then we know that Heinsmann was born no later than 1635, and possibly significantly earlier in the 1600s. It’s only 20 years between 1615 and 1635.

What else did Chris find?

Here is a Margaretha Müller, born about 17 December 1696 in Boltigen-Adlemsried. She moved to Bruchsal-Heidelsheim (Northern Wurttemberg, close to the Palatinate), where she married on 6 May 1727 and died on 15 Feb 1728:

https://www.geneal-forum.com/tng/getperson.php?personID=I20189&tree=ce

I looked up the original marriage and burial record, but no further information on her family there.

If Michael Müller was a widower at the time he married Irene Liesabetha Heitz in 1684, who was his first wife? Did she die in Steinwenden or in the area or rather already back in Switzerland? Maybe it is worth to have another close look at those burials in the Miesau church book from 1681 to 1684 to maybe find her there?

Alas, there was nothing more in Miesau.

Tom found a 1681 Boltigen record where one Michael Muller married Anna Andrist.

Is this our Michael, son of Heinsmann/Heinrich? We don’t have any way of knowing. Parents weren’t listed in these early records. Michael would have been about 26, a typical age for a man to marry at that time. Right time, right name, right place.

What do we know about Schwarzenmatt? Was it large or small? How likely would it have been to find two Michael Mullers of about the same age?

The Village and the Valley

We do know one thing. We’re getting a lot closer to Michael Miller’s cousin, Jacob Ringeisen. In the Steinwenden, Germany records, Jacob is identified as Michael’s cousin and is stated as being from Erlenbach, Switzerland. Schwarzenmatt is only 17 km away, or about 10 miles down the same valley, on the one and only road.

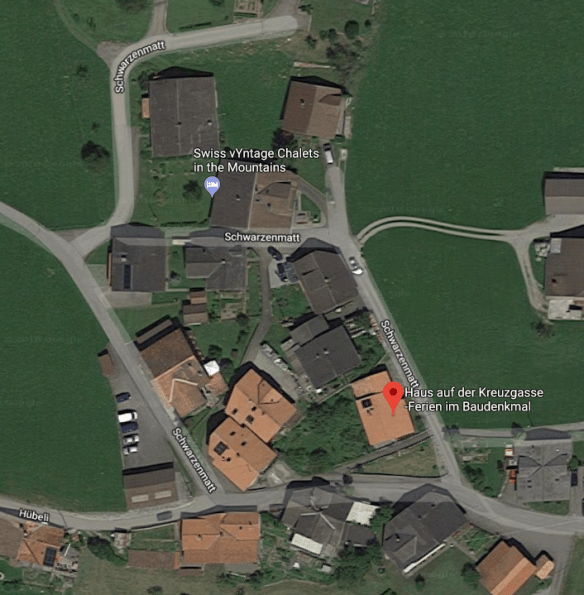

Schwarzenmatt today is a tiny village – about 150 feet East to West.

Clicking on the red balloon shows us the Swiss vYntage Chalets of Schwarzenmatt nestled in the mountains.

Looking at property booking sites (yes you can rent the chalets,) this red pin location is billed as a 400 year old house. If this is indeed true, then that property dates back to 1618, and would be one of the 4 original properties. Heinsmann or Heinrich Muller would have known this house and assuredly, visited, even if it wasn’t his.

Another house nearby is billed as 325 years old, so dating from 1693 or not long after Heinrich had died.

You can see a variety of photos here and here. Just click on the photos at left.

This winter view is stunning, as is the summer one below.

I love old photos! This is similar to what Heinrich and Michael Muller would have seen.

These black and white photos, even though they are from the 1900s, give us at least a peek at what life was like in this valley before the modern era.

Did Michael and Heinrich ski? Was skiing a way for residents to navigate in the winter instead of a sport like it is today? Note that tiny house.

Are these my relatives? I’d bet that almost everyone in or from Schwarzenmatt is my relative!

The alps are breath-taking.

Be still my heart.

I surely wonder what these men were carrying, and why. Did Heinrich do this too? They kind of look like human trees.

Seriously, I want to walk down this street beside the chalets. The entire village is only a block or two. I want to under those umbrellas and drink in the luscious mountain air.

Going for a walk, perhaps? What are they carrying?

The chalets and valley are shown here in an early aerial photo.

The Muller family may have lived in this valley for centuries before the first recorded history that includes the surname in 1615.

This place is stunning, no matter the season.

I’m so grateful that these preserved chalets provide us with a glimpse through the door to the past.

Looking at this door, I do have to wonder if it’s original, meaning perhaps was found in the village when Heinrich lived there. Did he open it himself?

Where did Heinrich Muller actually live?

Historian Peter Mosimann

Just when you think it can’t get any better, it does.

Chris found Peter Mosimann who, as fate would have it, wrote a book about Schwarzenmatt and even more miraculously, owns the Muller chalet. Yes, THAT Muller chalet.

The book is out of print, but here’s the forward, translated from German by Google translate. This isn’t the best translation in the world, but it certainly conveys the idea.

In 2009, the couple Mosimann the Earning a parent’s home, a former mountain farmhouse at the Kreuzgasse in Schwarzenmatt Boltigen im Simmental, dating back to 1556 and certainly one of the oldest houses in the Bernese Oberland is at all. Since the spouses do not live here themselves you can take with the foundation «Holidays in the monument» of the Swiss Homeland Security concluded a license agreement for thirty years.

The foundation had the house renovated and refrained from advise the preservation of monuments. When planning the renovation the thought came to the future holiday guests to make a booklet out of which they have something about the past of the house, the place and the valley could learn. This is now an extensive book from over 340 densely written pages, that you read with great pleasure and profit – even if you are not a holiday guest in Schwarzenmatt.

It is dedicated to Mrs. Mosimann by her husband, who since 2009 innumerable archives visited, innumerable books read and interviewed countless people.

Is in itself the approach of the couple Mosimann – the purchase of the house and its conversion – very much correct and praiseworthy, so does the book the whole still the crown on. Not only was the house saved, but also his story, including the story of one whole valley. Peter Mosimann has been through many sources worked, so to only the most extensive series to name, through twelve choral court manuals the Congregation Boltigen (1648-1875) and six choral court manuals the parish of Oberwil im Simmental (1587-1768) and thirteen parish registers of Boltigen (1556-1875) and fifteen from Oberwil (1562-1875). He has cleverly understood the “little” stories, which he found here to be associated with the “big” story, which he drew from the secondary literature. On example: standing in the gable triangle of the rescued house the year 1556 – at that time Emperor Charles V thanked Habsburg, in whose empire the sun never set, and set up the first parish register in Boltigen (page 30).

Everywhere you can feel the ordering hand of the former Secondary teacher.

The fact that at the house on the Kreuzgasse the former Saumweg led into Jauntal, not over the Jaunpass, but over the Reidigenpass, gives rise for a whole nice chapter about the traffic history. This is very clever with old and new.

Illustrated are photos showing tracks in the terrain sees who would miss out on the terrain itself.

The road led to Jauntal, the catholic («idolatrous») remained and for the severely reformed disciplined Simmentaler the country of vice – but also the temptations and pleasures par excellence – represented. But you also like reading the chapter about the “companions”, as there are: restaurants, Mills, saws, forges, a lime kiln, cheese dairies (initiated by Welschen Greyerzern!), school houses, castle ruins and stones. It’s not just the good, but also the bad old time to the language, alcoholism, the poor, home and child labor, at the for a few cents matches for the matches were produced in Wimmis.

The result is a home customer in the best, namely in the critical sense of the word.

Peter Mosimann is not content with the old one time, but asks to the present. He speaks from the revival of livestock in the Simmental in the 19th century, from the introduction of electricity and the damming of the simme. He is very well aware that in today’s, rushing changes a whole world to disappear threatens, and he therefore has older Simmentaler asked about their knowledge and memories, so operated “oral history”. A nice example is the reconstruction a mining year around 1960, probably with the help of his wife and in-laws. Only here it becomes clear how far already 1960 – not 1860 and also not 1760! – is past. Especially nice and consistent is when people each speak for themselves: one Hemmer sitting in a tavern in Freiburg had shared the bed a bit too much (p. 94), the Daughter of the Wegmeisters Eschler, in the first half of the 20th century for the maintenance of the Jaun pass was responsible (p. 111 f.), the last geisshirt of Eschi (p.180 f.) Or Peter Mosimann’s wife Berti itself, from which the last chapter comes, that the house is dedicated in Schwarzenmatt. Or from the pastor of Boltigen, who died during the plague at the end of the 16th / beginning of the 17th century. Century not only lost all his children, but also three wives (pp. 12 f.). So sad this last one.

History is – you can Mr. Mosimann to his just congratulate factory.

State Archives Freiburg

PD Dr. phil. Kathrin Utz Tremp

Scientific Associate

In essence, we can thank the ski industry today for encouraging the salvation of these old chalets.

These lifts are only a few miles away and tourists need a place to say. Who wouldn’t love to stay in an alpine chalet?

The Swiss Alps tower above Schwarzenmatt and Boltigen.

The Muller Chalet

Chris found several links, and more information. This photo taken about 1912 in front of the chalet shows:

“Susanna Katharina and Friedrich Bhend-von Allmen with their children Fritz, Karl and Hans.”

Peter Mosimann’s wife’s father was Hans Bhend, so Susanna Katherine was apparently a Miller by birth, perhaps a descendant or at least a relative of Heinrich Muller from the middle 1600s. I would so love to see if my mother or other Miller descendants would match her DNA!

This house was built in about 1556 and was in the Muller/Miller family from before 1615. I can’t help but wonder how the date of 1556 was established. Perhaps by tree ring dating of the wood (dendrochronology.)

There is no ownership record before the Muller family, so they could have built it. In 1872, David Muller sold the property to his son-in-law, Freidrich Bhendd. Peter Mosimann’s wife was born a Bhend and grew up in this same house, shown above.

The article, in German, also shows additional photos.

I can’t reproduce the article here, but I can summarize.

Peter Mosiman, the local historian, states that this is one of the earliest dated peasant residential buildings in Boltigen and perhaps in all of the Bernese Oberland.

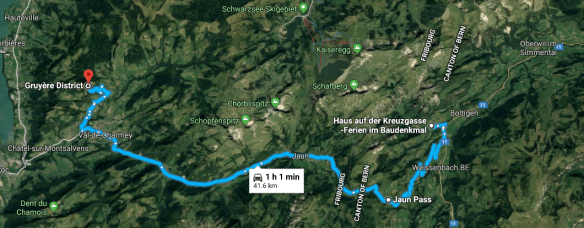

The sunny location where the house was built was on the mule track over the ridge to Juan and then to Gruyere, although the translation suggests that the house was on the path to Juantel, which I cannot locate on a current map.

I do wonder this this village was a stop-over location, and people rested the mules at this farmstead.

The ancient Juanpass through the mountains is first mentioned in 1228 as Balavarda and again in 1397 as Youn. Was the Muller family here then? What originally brought them to this high, remote location, and when?

The road was paved in 1878 and today is on the list of the highest paved roads in the world. Looking at the map, you can see the switchbacks. The pass peaks at just below 5,000 feet, the ascent 8 miles long and rising almost 2000 feet.

By Norbert Aepli, Switzerland, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=807797

Take a look from the pass here.

The photo of the pass, above, is exactly how I remember the Alps.

Here’s the same map with Gruyere, on the other side of the mountain, added.

I have to stop and admit right here that I love the Alps. And I mean LOVE them with all caps. I spent an amazing, life-changing summer in 1970 living in Versoix, Switzerland and spending time in those beautiful mountains and meadows not far from this very location. If you could see across the mountaintops, I lived about 25 miles as the crow flies. I know, what are the chances??

The summer in ski resorts is an inactive time. I spent a month or more there, hiking and wandering the beautiful alpine meadows. Today that resort is Crans-Montana, but then it was a sleepy, tiny Swiss mountain village.

The fact that my family actually originates here stirs my heart and touches my soul in a way I simply cannot put into words. It feels like my ancestors reached out to me, infusing their love of these mountains, even though I didn’t know them then.

But back to the Muller chalet.

Peter Mosimann says that he has documented the house ownership back to at least 1700 in the Muller family. Clearly, Heinrich lived in Schwarzenmatt in the first half of the 1600s. He would have been born either in or before 1635, probably right in this village or at least this valley. Most likey in this peasant house.

The walls were wood and stone that came from the surrounding area. Some stones are outcrops of the mountainside on which the house perches. The stones were connected with lime mortar and whitewashed. A stable was connected to the house, and the “goat-lick” still survives and is shown in photos in the document. Do you know what a goat-lick is? Neither did I!

The ground floor originally only had one small room. A “smoke kitchen” allowed the smoke to drift up between the slats in the rafters where meats were hung to be smoked and cured. The beams there are still black with centuries of accumulated soot.

Water came from the village well or fountain. Schwarzenmatt was lucky and had their own well. Kreuzgasse, the street where this chalet is located had their own fountain.

When I hiked the Alps, we drank from the icy-cold streams, although we were warned about drinking only near the headwaters because mountain goats tended to contaminate the water. We didn’t worry much about that.

In the Muller chalet, it appears that there was a loft type of structure upstairs where the children slept. They warmed some type of sack on the stove and took it to bed with them. Of course, as a quilter, today I think of this in terms of a quilt.

The original windows were sold at some time and installed in a restaurant in Obersimmental, about 10 miles distant. The homeowners thought they got the better end of that deal, because they installed new windows which were surely more winter-resistant, weathertight and warmer.

Clothes and dishes were washed in a basin on the table, and clothes were dried on a wooden rod in the kitchen.

Plums, pears and apples were dried for the winter to go along with the smoked meats.

Peter says that the renovation exposed 1705 construction with holes in posts suggesting that earlier building had occurred and the 1705 construction itself was either an expansion or a remodel. A stable was added at that time to house 4-6 goats and two pigs.

A cheese tower yet preserved shows that cheese was manufactured on this farm. Three circular pieces of wood are attached to a pole set in stone and connected to the rafters.

Chris located a photo before the renovation occurred.

Drum roll please…here’s the beautiful chalet today from a different angle. And look, just look at those mountains.

This chalet even has its own Wikipedia entry. At this link, you can see what it looks like in the winter. Another photo here and the renovation here.

The Muller Chalet, shown with the red pin below, is almost next door to the Swiss Vyntage Chalets I first found on the booking site.

I can’t tell you how much I want to visit this location and see the Muller chalet in person. Actually, I don’t just want to see it, I want to stay and sleep there, basking in the ancestral glow.

Johann Michael Muller

We know that Michael Muller, a widower, who married in 1684 in Steinwenden was from Schwarzenmatt. We know that a Michael Muller married in Boltigen in 1681 in the church where the Schwarzenmatt residents attended. There was no other church in the valley. The question is, is this the same Michael Muller?

This area was very small at the time, not to mention remote. Chances are very good that the Michael who married Anna Andrist was the same Michael Muller, but there could have been more than one. We also know that our Michael’s father was Heinrich, recorded as Heinsmann in Germany, who was from the tiny block long village of Schwarzenmatt.

In Switzerland, when a resident left, they were required to register. In essence, they carried a lifelong passport with them and as long as they left in good standing, they could always return as a citizen.

Those rolls were called Mannrechten and they exist for 1694-1754 from the Bern region. Of course, that’s after our Michael left, but several Millers from Boltigen were listed. Chris checked with the archives, and has kindly translated their reply, as follows:

– There are no “Mannrechtsrodel” earlier than 1694, so probably no direct proof of Michael Müller`s emigration to Germany.

– Mr. Bartlome (archivist) writes that at the time no permission was required to leave Switzerland. However, there was a heavy tax on money transferred abroad (“Abzugsgelder”). If an emigrant transferred money abroad, at the same time the emigrant passed on their citizen rights in Switzerland. This was done to prevent the emigrants possibly returning to Switzerland later on as a poor person.

– Only around 1700 an alphabetical name register was started for Swiss citizens who passed on their citizen rights. The register (listed in the link above,) is such a register. Please note that this passing on citizen rights could be done by children or grandchildren of the original emigrant! So the listed persons are not necessarily the emigrating persons!

– The register does not list the emigration date, but the date on which the citizen rights were passed on, plus the money that was transferred abroad and to which place.

– Finally, Mr Bartlome notes that emigrants may also be found in the protocols of the Bern government (“Ratsmanuale”). The transferred money (“Abzugsgelder”) was also listed in bills of the bailiffs (“Rechnungen der Landvögte”). So this may be another way to find emigrants in old documents, but it is a tedious process and with no guarantee.

As Chris comments, clearly not what we had hoped, but still, the door isn’t entirely slammed shut.

Chris later discovered a list of Swiss emigrants from 1694-1754 who settled in the Palatinate, Alsace-Lorraine, Baden-Wurttemberg and Pennsylvania in an article by Kary Joder in the October 1983 Mennonite Family History Newsletter, Volume II, #4, available in the book section at Family Search. In this document, one Michael Miller is noted on page 136, along with Miller men from Boltigen, as follows:

Chris wondered where my Johann Michael Miller the second, the son of the original Johann Michael Miller, from Schwarzenmatt, was located in 1720.

Chris translates from the original German version:

“2.12.1720 Michel Müller von hinter Zweisimmen zieht nach Leistadt (Bad Dürkheim).”

Translation: “2 December 1720 – Michel Müller from behind Zweisimmen moves [read: “his money”!] to Leistadt (Bad Dürkheim).”

Could this Michel Müller possibly be identical with Michael Müller the Second? I am not as familiar with his life dates as you are, so I have to ask you if this remains a possibility. I know that in 1721 he became a citizen in Lambsheim. Lambsheim and Leistadt are 8.5 miles apart from each other. Do we know for sure that in 1720 Michael Müller the Second was still in Steinwenden or was he maybe “on his way” to Lambsheim?

“From behind Zweisimmen” suggests to me that possibly this Michel Müller could not name the place of origin of his father. “Behind Zweisimmen” would definitely go well along with Schwarzenmatt. Zweisimmen and Schwarzenmatt/Boltigen are only 6 miles apart from each other.

It’s amazing how quickly ancestral knowledge of locations and events fades. By 1720, Michael Muller the first had been dead for 25 years, having died when his son was only 2 years and 3 months old. It’s no wonder that Michael Muller the second couldn’t remember the name of the town in Switzerland where his father was from. He never knew his father – only through his mother’s remembrances.

In April of 1718, Johann Michael Muller (the second) is identified as the farm administrator of (the farm) Weilach in a baptismal record for his child in Kallstadt. He is still living in Weilach on April 5th, 1721, but by January 15, 1722, when he is once again mentioned in a Kallstadt baptism record where he stands up as a godparent, he is a Lambsheim resident about 12 miles distant from Weilach. Citizenship records tell us that Michael moved to Lambsheim between April and July of 1721.

As the map above illustrates, Leistadt is very close to Weilach and Kallstadt, both. It was less than a mile from Weilach to Leistadt, the closest village. Certainly close enough to walk. The Michael Muller on December 2, 1720 who moved money from Schwarzenmatt to Leistadt is very likely Michael Muller the second, son of the Michael Muller the first, son of Heinrich Muller. Perhaps he moved the funds in preparation for his move to Lambsheim. It was only a few years later that he emigrated to America.

Until that time, Michael Muller the second had been a Swiss citizen, although he was born in Germany.

Mullers in Boltigen and Schwarzenmatt

The Mullers were clearly visible in the Boltigen area, which includes Schwarzenmatt. Several (in addition to Michael) were mentioned in the Mennonite document that references moving money.

- Muller, Benedicts from Boltigen to Eppingen-Churpfalz on November 29, 1726

- Muller, Wolfgang from Boltigen to Maulbronn-Wurttemberg on May 6, 1732

- Muller, Johannes from Boltigen to Horbach-Swiebrucken on March 14, 1754

These three Miller men transferred funds to the same region of Germany, near where Michael had moved.

Were all of these men from the same Muller family from Schwarzenmatt and Boltigen?

Were there multiple Miller families living in Schwarzenmatt or Boltigen by that time?

If so, did they descend from a common Miller ancestor, or different men that just happened to carry the same surname?

Is this the same Muller family that had a coat of arms awarded in 1683, right about the time Michael Muller the first is found in Germany?

The Miller family in Boltigen had a coat of arms awarded in 1683 which looks to be a cogged wheel of some sort, perhaps a miller’s wheel?

The history of German heraldry isn’t terribly helpful, except to say that noble coats of arms included a barred helmet, and burgher’s/patrician’s coats of arms included a tilted helmet. The Muller coat of arms includes neither, so this tells us that the family wasn’t noble. It’s noted that in Switzerland, in the 17th century, Swiss farmers also bore arms. Given that the Schwarzenmatt Muller family, as evidenced by the restored home, was clearly a farm family, the coat of arms isn’t as surprising as it might otherwise seem. I am very curious though at the meaning of the yellow symbol on the coat of arms and if the blue background has any significance. I also wonder if this coat of arms would have included “all” of the Muller family or clan, or only one specific family unit.

There’s no way, of course, without Y DNA testing or non-existent records to tell if this is the same family. The Boltigen church records were lost in a fire in 1840. I have a DNA testing scholarship for any Miller male from the Schwarzenmatt/Boltigen area, or whose ancestors lived there.

A painting, below, remains of the old Boltigen church and parsonage from 1822, before the fire. This would have been the church that Heinrich attended, and where Michael was married in 1681.

From this photo of the current church, built after the 1840 fire, it looks like the new church was built in the same location and in the exact same style and footprint as the old church.

By Roland Zumbuehl – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20634682

Boltigen is just down the valley, about a mile from Schwarzenmatt. A lovely Sunday walk to church.

You can walk home from church in half an hour, but of course, it’s uphill! Probably not very pleasant in the winter.

Schwarzenmatt was tiny then and it’s tiny now. Heinsmann (Heinrich) and Michael lived here – lost in time today, but not lost to memory anymore.

Leaving Schwarzenmatt

This part of the world is truly beautiful – nature at her finest. I wonder what compelled Heinrich’s son to leave. It’s certainly possible that the isolation was a factor. The family that lived in this house, with who knows how many children, were peasants, and their children would be peasants too. Perhaps Michael wanted something more. Perhaps he found no comfort here after his wife died. Did she pass away giving birth to their first child?

The Thirty Years’ War had devastated and depopulated most of the Palatine and the Swiss were invited to come and settle, tax free, with a promise of land. Looking at the tiny Swiss village, and having lived in the Alps, I understand that this area could only support a limited population and had little potential for expansion. The German offer meant, for Michael, that opportunity was knocking and perhaps providing an escape from the pain of his wife’s death.

Once Michael left Schwarzenmatt, given the distance to Steinwenden, he likely never returned, which meant he never saw his parents or family again. Perhaps both of Michael’s parents were deceased before he left. We know, according to his marriage record in 1684 that his father was already gone by that time, but what about his mother and siblings – assuming he had siblings?

Heinrich likely was born and died in Schwarzenmatt and is buried in the churchyard of the old church that burned in 1840. Perhaps generations of Heinrich’s ancestors are buried near him there as well.

Michael would have passed that location one last time, perhaps stopping to say one final goodbye to his father and wife, on his way down the valley, through the village of Erlenbach, perhaps gathering his cousin Jacob Ringeisen, on his way to Germany.

Heinrich was the last of his generation here, at least in my line, and Michael was the first generation in Germany.

We think of the Muller family as German, but in reality, Michael the first only lived in Germany as an adult, retraining his Swiss citizenship the entire time. His son, Michael the second lived in Germany until 1727 when he emigrated to the US. He only relinquished his Swiss citizenship in 1720. In total, the Muller family lived in Germany for between 43 and 46 years. They were only exclusively German, meaning no Swiss citizenship, for 7 years. Before that, they were Swiss, probably for generations. After that, American.

How long had the Muller family been settled in Schwarzenmatt? When did they arrive? And from where? Is the surname Muller the trade name for the local miller? Does it reflect the occupation of Heinrich or his ancestors? Were they millers on the creek that runs through the valley?

We don’t have answers to those questions, but we can look at what the Miller line Y DNA tells us.

Genetic History

Our cousin, the Reverend Richard Miller took the Big Y DNA test in order for Miller descendants to learn as much as possible about our heritage.

Our Miller terminal SNP, or haplogroup, is R-CTS7822.

| SNP | Estimated Age |

| CTS7822 | 5000-5300 (Bulgaria) |

| Z2109 | 5300 (Russia, India) |

| Z2106 | 5300-5500 |

| M12149 | 5500-6100 |

| Z2103 | 5500-6100 |

In the R1b Basal subclade project, our sample is the only one with a terminal SNP of CTS7822.

There are other people who have another SNP downstream that we don’t have, some in Germany and Switzerland, and many in Scandinavia. Those would be descendants of CTS7822. In other words, at some point in time, a branch of the family headed north, long before surnames were adopted. Another branch headed south, across the Alps to Italy. One branch is found in Bulgaria and another in England.

Z2109, the branch immediately above ours, also our ancestor, is found in India, the Russian Federation and Turkey. That’s a fascinating span and suggests that the person who carried the ancestral SNP, Z2109 might well have been in the Caucasus before his sons and their descendants fanned out in all directions.

Unnamed Variants

Perhaps even more exciting is that eventually our Miller line is likely to have a different terminal SNP. Cousin Richard has 36 total unnamed variants.

This means that mutations, SNPs, have been found in these locations on his Y chromosome that have never been found before. These SNPs aren’t yet named and placed on the haplotree. Our line will be responsible, when another male tests that has these same locations, for 36 new branches, or updated branches, on the Y tree.

I always knew our Miller line was quite unique, and Heinrich’s Y chromosome, passed to Miller men today proves it!

Heinrich Muller’s DNA will be providing new discoveries in a scientific field he had absolutely no clue existed. His final legacy wouldn’t be written into record until more than 337 years after his death in the tiny village of Schwarzenmatt in the Swiss Alps. Not chiseled into stone, but extracted from his descendants Y chromosome.

Reflecting

I know this is the last stop on the Miller/Muller road, in this picturesque tiny village in the Swiss alps. There are no more records. I am attempting to contact Peter Mosimann, and if I’m lucky, there may be more photos!

With the difficulties in colonial America determining who Michael Miller (the second) was, and where he came from, never in my wildest dreams did I think we’d find our original homeplace in Switzerland two generations earlier.

And not just Michael’s home location, but his actual swear-to-God home, as in house.

I’m still reeling from this stroke of amazing luck – but then luck favors the prepared. My amazing German genealogist and cousin, Tom and my German-speaking friend, Chris receive all the credit for their amazing sleuthing work. None of this would have happened without their diligence.

I am ever so grateful.

I have wanted to visit Germany for decades. With this latest discovery, I’m checking airfares. My husband is in the other room having a coronary at the potential cost of the trip, but I’m focused on the emotional toll of not going. I always regretted not taking my mother back to Mutterstadt before her death, and count on it, she’ll be accompanying me in spirit😊

Maybe she has been guiding the way all along.

It was a long journey, in terms of miles, ships and time, from Schwarzenmatt to where I sit today. Ten generations and almost 400 years of mule paths, rutted wagon roads and 3-masted ships. From a farmhouse of stone and wood on a mountainside sheltering people, goats and pigs, with water hauled from the community well to an electrified dashboard from which I can travel the world, even back to Schwarzenmatt, without leaving my driver’s seat.

Yet, I know that there’s nothing like visiting in person. Walking where Heinrich walked. Standing where he stood. Visiting his grave, or at least the graveyard where he, his wife and their ancestors are surely buried in unmarked graves.

I hope to be reporting back to you in a year or so from Schwarzenmatt as I trace my ancestors’ footsteps and generations back in time.

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- Family Tree DNA

- MyHeritage DNA only

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload

- AncestryDNA

- 23andMe Ancestry

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists for genealogy research

Discover more from DNAeXplained - Genetic Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

And now I am more convinced than ever that my German ancestors will not be researched by me!

I am a descendant of Heinrich Muller of Wurttenberg, Germany.

AND

the Ninth Early of Argyll through my Campbell (and Rhea) ancestors.

So, when I stumbled upon your website last night, I became quite intrigued.

My family records record various Campbells and Rheas who migrate from Virginia to Tennessee.

Loch Fyne is the former land of Clan MacEwen first holders of Argyll, who later came under the protection of the Campbells. I am a MacEwen on my mother’s side. It looks like I will need DNA to find the which MacEwen is the immigrant ancestor from Antrim, Ireland to America.

Other Swiss/German ancestors came from Alsace-Lorraine, Geneva, Eisen – all the places in your ancestry.

I now live in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Lee Muller

My husband and I visited Basel, Switzerland three years ago. Switzerland is both gorgeous and expensive. It must be exciting to trace your Swiss ancestors so far back in time.

Do you know whether many Jews settled in Switzerland? I have a few distant cousin matches from Switzerland but don’t know if they are truly cousins.

I don’t know.

All of Europe is expensive. I had a bit of sticker shock.

Yes, that’s true!

Always fun tracking someone named Heinrich Müller. In my case a cousin married a guy by that name in NYC. LIke many, he changed his name to Miller. His son was named Henry Valentine Miller . . . who went on to write books about, I guess, travel to the southern climes . . . a couple of them all started with the words “Tropic of . . .” 😉

Thank you so much Roberta for the information. If my grandmother Rilla Miller Landon was alive she would be smiling.

I can see that you have a Hans-Heinrich Muller in the Mennonite Family History Newsletter, on top of having a Heinsmann (Heinrich) Muller. Heinsmann sounds a bit like Hans.

I have an (likely) ancestor in New Amsterdam/New York that is causing me trouble because of his changing name. He has all kinds of spelling variations for his most commonly used name: Hendrick. He is also found as Hans and as Adam… and Henry. I would have to find my list to make sure that I list them all. The thing is, his probable son is found in New France, where his father’s name is given as Jean (normally translated as John, Johannes/Hans). I have a hunch that translations didn’t follow the rules we would follow today. Adam and John don’t even have the same ethymological root as Henry, but it didn’t seem to bother the settlers on any side of the border. I am working on building a list of documented cases of such “weird”/irregular translations (or nicknames/name variants within a single linguistic community).

This case interests me a lot since it’s even the right first name: Heinrich/Heinsmann/… Hans(?).

Is it really common in Germanic (or English-speaking) countries, back in the late Renaissance/colonization period, to call a Hendrick (or Heinrich) also by the name Hans (or its semantic equivalents), willy-nilly, following the mood of the moment? You seem to have a lot of ancestors from these Germanic parts of Europe, so you might know of numerous examples. I could really use them, especially if you have a link to the man in question on Geneanet (or the like) so that I can provide an actual identity on top of you as a reference. (This research will be published in the form of an article if my theory proves to be well founded.)

Marie-Pierre Lessard

You wrote:

“From behind Zweisimmen” suggests to me that possibly this Michel Müller could not name the place of origin of his father. (…)

It’s amazing how quickly ancestral knowledge of locations and events fades.

I have another explanation for this. I live in Denmark, and I can tell you that even today, Danes often don’t bother telling each other the name of the small town they come from or currently live in, especially if they are talking to someone who is not from that area. They just don’t expect the person to know where that is, so they stick to the name of a place that will be known to their interlocutor. I see that behavior all the time.

My personal guess is that since he was abroad, he didn’t bother to tell the “dude” the name of a place lost in the middle of the Alps. He stuck to a bigger village/town, which would have known (or more likely to be known) by this interlocutor.

We can’t expect our ancestors to think of their posterity’s confusion when they were dealing with clerks, hundreds of years ago. 😉

“I also wonder if this coat of arms would have included “all” of the Muller family or clan, or only one specific family unit.”

I have some insight to give you on that as well. I am not a top expert on Danish coats of arms, but something could happen with a coat of arms when one family united with another through marriage. The coat of arms didn’t change at every generation with a new wife from another noble family, but once in a while, they created a hybrid. It’s conceivable that if those Mullers shared a great-grand-father, for instance, they could all have the same coat of arms.

Coats of arms can actually be key to determining your genealogy (at least in Denmark). I imagine that if you learn the rules of acquistion and transmission of coats of arms, you might be able to know for sure if those men were related. Based on the Danish rules, I would assume that if all those men used the same coat of arms, they would all be related, but not necessarily brothers, or cousins sharing the same grandfather. The common Muller ancestor could be much further back.

Oh, but I just realized it’s a newly acquired coat of arms, not one from centuries before, so if they share the coat of arms, their common ancestor couldn’t be 300 years ago… (I imagine that the German rules couldn’t vary that much from the Danish ones.)

He, he! That’s what a coat of arms is. It’s an old fashioned Y chromosome marker. 😉

But then, the difficulty becomes to find proof that each of those specific men were using that same coat of arms. It’s still a challenge. 😀

If you’re really lucky, you’ll find evidence that your Muller/Miller immigrant ancestor used that coat of arms after his arrival in the New World. It’s quite probable that the remaining branches in Europe kept using it until it became out of style, or until they lost the rights to it somehow.

In my French family tree, I am finding a lot of French names that have coats of arms associated with them (potential relatives, to be proven), but heraldry wasn’t used much in New France, as far as I know. Maybe the practice was different in the 13 colonies.

In France, about 30% of coats of arms registered were noble. The other ones were usually for merchants and professionals, but some peasants also had them. I am mentioning that in order to stress the importance of understanding the rules and practices of each country in order to use coats of arms effectively in genealogy.

I’m fairly sure that’s a wheel of a water mill in the coat of arms.

Thank you for a fascinating story. This is what family history is all about.

“The Miller family in Boltigen had a coat of arms awarded in 1683 which looks to be a cogged wheel of some sort, perhaps a miller’s wheel? […] I am very curious though at the meaning of the yellow symbol on the coat of arms and if the blue background has any significance”

The first thing to know about colors in heraldry is there are two categories, metals and colors. The metals are white, named silver, and yellow, named gold. The colors are red, bleu, green and black (they have more exotic names, but let’s keep it simple). It is bad taste to put metal on metal or color on color. Following this rule, see how the Union Jack is making sure the top red cross doesn’t touch the st-andrew red cross behind.

So the blue background is a color and the cogged wheel is a metal. Knowing the surname is Mueller, I would guess the blue background represent water and the cogged wheel a water mill’s wheel. The coat of arm seems rather descriptive, event illiterate peasants would guess it belongs to a guy named Miller.

As for why golden wheel… maybe because that’s where a miller get his wealth from?

Incredibly beautiful country – it reminds me of the Washington Cascades 😉 Was this from your recent trip to Germany, or was this in preparation for the trip? I wasn’t sure, as you mention reporting back in a year or so. You didn’t happen to come across any Schmidts while you were there, did you? I’m still searching through a gazillion immigrant Schmidts.

No, I just found this recently. I wasn’t anyplace close on the recent trip.

I am wondering whether your immediate positive feelings about the Alps when you first visited them might be due to genetic memory. What do you think about that theory?

I actually do wonder about that. I’ve had the phenomenon elsewhere too.

I have experienced that before as well, on several occasions, with ancestors born hundreds of years ago. Weird!

I have a pretty stunning anecdote to share about that. A long time ago, before I got into genealogy, I watched a miniseries about Henry VIII (the one with the 6 wives). Since I am French Canadian, I was not very familiar with every detail of the story, so some parts were completely new to me. When we reached the part about how John Hussey’s wife got him in trouble by defying Henry VIII, I knew right away that this was incredibly dangerous for her husband. I could feel it in my gut. When we reached the part about his military failure, I was waiting with dread. When I learned about his beheading, I felt physically ill. I felt so nauseous that I had to take a break and walk away. I don’t normally react with such intensity to small-screen drama.

Recently, I found out that I descend from Christopher Hussey of Nantucket, Massachusetts. His ascendance is still being debated and considered uncertain, but you know what, I just know…

I fully understand.

I have one ancestors story that I actually can’t read.

I have not had such intense experiences as you, but I have had the experience of “just knowing” that is not based on normal evidence. Sometimes we called it a gut feeling or instinct, but genetic memory sounds right to me.

I had a similar gut feeling when we visited Vienna, yet I don’t know how to explain it. My mom used to watch the Sound of Music every night, which took place in Salzburg near the Alps

So true! Sometimes, that gut feelings help choosing the right research avenue in order to find the supporting documents. I tend to trust my gut, especially when the documentation is elusive, and it’s like looking for a needle in haystack.

Of course, that inner feeling we have is only true to us (one person in the world) until we find those documents! There is something to be said about not having preconceived ideas. Roberta stressed that point several times. Let’s call it a hypothesis that you can test in order to prove (or disprove) it.

I’ve seen glimpses of the Alps while on a train from Paris to Milan. The Alps are awe-inspiring even if you have no genetic ancestors from that region. Who knows, perhaps my Italian and Spanish Jewish ancestors crossed the Alps into Germany and Austria so very long ago!

Roberta, thank you for another wonderful story!

As an additional note: The German article about the house states that the year “1556” is engraved below the roof – so, no dendrochronology required. 😉

For those interested in the Müller coat of arms: The painting is derived from a preserved glass window in the Bern Historical Museum. To my understanding, the window was originally placed in the choir of the Boltigen church. I only found a low-quality picture online: https://vitrosearch.ch/data/thumb/2267534.1510854824.jpg

(The Müller coat of arms is on the right side.)

Since the window is from 1683, the coat of arms may have been awarded much earlier.

Thank you, again!!

“Since the window is from 1683, the coat of arms may have been awarded much earlier.”

That is indeed possible, Chris! Based on my experience of French coat of arms, I can say that they were eventually registered in the “Armorial général de France.” The point of this registration was to collect a new type of taxes (from 1696). Some people simply refused to get their ancestral coat of arms registered, in protest.

Since one country sometimes takes inspiration from another, you might want to check if those coats of arms existed already and only got registered in 1683 because of a new law.

That would be the difference between “registered” and “awarded.”

I have just seen something in a WDYTYA episode about the British College of Arms. In order to get registered, one had to pay a fee. With this fee, the applicant also provided a pedigree. If you can establish that your line connects with the Mullers who received/acquired/registered a coat of arms, you should check with the corresponding “college of arms” to see if they have information about the family, in particular a registered pedigree (as per the English custom).

Consider the given name Hansmann that I have found in the area around Payerne in the 16th Century, an area that was controlled by Bern but also heavily influenced by Fribourg. Another popular given name of this type was Petermann. At some point (and probably at different times in different places) these and many other non-standard non-Biblical names were officially discouraged by the Reformed Church of Bern (the official state church for Bern and its vast occupied territories at that time), and so they have disappeared. Also, I would tend to think of “hinter Zweisimmen” as an actual place name, “Hinter-Zweisimmen” (meaning the part of Zweisimmen toward the back). A closer look at local toponyms in old records might be helpful.

Pingback: The Muller House on Kreuzgasse; Humble Beginnings in Schwarzenmatt, Switzerland – 52 Ancestors #229 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Heintzman Muller and the Mystery of the Boltigen Choir Court Window – 52 Ancestors #313 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

I was truly blessed to live in Steinwenden for 3 years while stationed at Ramstein Air Base. I was a member of the Tannenbahm Ski Club on base and we’d take monthly ski trips to Interlaken, Grindlewald, Innsbruck, and many other places in the Alps. Thank you so much for this very helpful article. I really appreciate it. I hope you and your husband make the trip to these areas. You can’t afford not to.

Ironically, my niece and her husband were stationed there years ago too. Long before I knew about the connection. I would love to have taken my

Mother to visit.

Hey Roberta

My Name is Yanick Müller

I never knew my grandfather because he died before i was born..

But i know that he was born in Boltigen (Schwarzenmatt)

I just read your post and think that maybe there are some connections?

If you want to contact me write me an email on yanick-tcg@bluewin.ch