Robert Eastes, reported by family researchers as a mariner, was born about 1555, probably at Deal, Kent, and died about 1616, at age 61 in Ringwould, Kent. He married Anne Woodward on December 2, 1591 at St. Nicholas Church in Sholden, Kent, just a quarter mile or so up the road from St. Leonard’s Church of Deal where the Estes family was a long-time member.

Robert Eastes and Anne Woodward were married in St. Nicholas church at Shoulden, in this chancel, minus the carpet of course. Anne would have walked up this aisle 423 years ago.

Anne Woodward was born about 1570/1574. Baptism records began to be kept in 1569, so hopefully a record for her still exists in some location and has simply yet to be found. It’s likely that her family attended the church at Sholden as well and she may well have been born there and baptized in this very font that still exists in the church today.

Anne made her will on April 21,1630. She was buried on May 18, 1630 at Ringwould, less than a month later. Her will was probated on June 9, 1630, and listed nine children. Unfortunately, the archives cannot locate Anne’s will and now claims that it doesn’t exist. Perhaps it is filed under a different surname spelling.

Robert and Anne spent the first few years of their married life at Sholden, moving to Ringwould by September, 1595, according to baptismal records of their children.

Robert’s parents were Sylvester, a fisherman, who died in 1579 when Robert would have been 24 years old, and Jone, his mother, who was buried at St. Leonard’s Church in Deal in 1661, when Robert would have been about 6. Eighteen years later, Sylvester died, but would be buried in Ringwould for some unknown reason. There is no record of Sylvester remarrying. So when Robert Eastes married Anne Woodward in 1591, neither of his parents could attend his wedding.

If Robert was born in 1555, he waited quite some time before marrying. In 1591, he would have been 36 years old. I have to wonder, especially if he was a mariner, if the English war with Spain might have had something to do with his delayed marriage. During this war, the coastline of Kent was on high alert. The Spanish Armada was expected to attack at any minute, and indeed, in 1588, they did move up the English Channel in an arc preparing to attack England.

However, between the weather and the English “Navy” such as it was with few warships and mostly conscripted merchant and fishing boats, the Spanish were defeated off of the coast of France.

Nonetheless, the watch for the Armada had been underway in Kent, between Dover and Deal, night and day in specially constructed watchhouses, along the Kent coastline that was preparing to take the brunt of the battle.

Deal and the rest of the coast prepared, as best they could. Deal is reported to have had six vessels ready, along with the men to man them. Robert, at his age, 33 at the time, had to be involved in some capacity.

The English fleet may have been victorious, but they weren’t out of harm’s way yet. The English fleet anchored in the Downs to allow their victorious crews to be paid off before they were demobilised and dispersed. However, a gale wind blew for several days, stranding the entire fleet. An infection caused by “sour beer” disabled the crews. The gale, still blowing, made the transportation of supplies, food and medicine to the stranded ships impossible. The crew, without pay, turned mutinous. Slowly, boats managed to land thousands of sick and wounded seamen who then lined the beaches, “dying where they lay,” at Deal, Sandwich, Margate and Dover. Sir John Hawkins, pirate, treasurer of the Navy, hardened seaman, slave trader and adventurer wrote that, “It would grieve any man’s heart to see them that have served so valiantly to die so miserably.” Anything that could touch his heart must have truly been horrible.

If Robert were a mariner, he was understandably busy, not to mention that warfare disrupts commerce. Maybe he couldn’t afford to marry until 1591. Or maybe, he just hadn’t met the right young woman. But he did marry and he and Anne had a family.

It’s interesting, because Anne, based on the marriage and birth date of her first child was three months pregnant then they married, which may have been why they married when they did. I noticed in Ringwould that church records were pretty unforgiving and very direct about illegitimacy if the parents remained unmarried at the time of the child’s birth. However, Robert and Ellen married and there is nothing in the child’s baptism record that indicates anything “odd.”

While today, we think of a wedding as a definite legal dividing line between married and unmarried, in the past, marriage was more of a process. In fact, the betrothal was the beginning of the marriage process and that is when sexual relations, referred to as spousals, began as well. Children conceived while betrothed but before marriage were considered legitimate as long as the couple married.[1]

The term “processual marriage” is sometimes used to describe these arrangements, that is, “where the formation of marriage was regarded as a process rather than a clearly defined rite of passage” (S. Parker Informal Marriage, Cohabitation and the Law, 1750-1989).

It is no longer generally recognized that the Anglican marriage service was an attempt to combine elements of two separate occasions into a single liturgical event. Alan Macfarlane develops the point in detail: “In Anglo-Saxon England the ‘wedding’ was the occasion when the betrothal or pledging of the couple to each other in words of the present tense took place. This was in effect the legally binding act: It was, combined with consummation, the marriage. Later, a public celebration and announcement of the wedding might take place — the ‘gift’, the ‘bridal’, or ‘nuptials’, as it became known. This was the occasion when friends and relatives assembled to feast and to hear the financial details. These two stages remained separate in essence until they were united into one occasion after the Reformation. Thus the modern Anglican wedding service includes both spousals and nuptials (Macfarlane).

This pre-modern distinction between spousals and nuptials has been largely forgotten; indeed, its very recollection is likely to be resisted because it shows a cherished assumption about the entry into marriage — that it necessarily begins with a wedding — to be historically dubious. Betrothal, says Gillis, “constituted the recognized rite of transition from friends to lovers, conferring on the couple the right to sexual as well as social intimacy.” Betrothal “granted them freedom to explore any personal faults or incompatibilities that had remained hidden during the earlier, more inhibited phases of courtship and could be disastrous if carried into the indissoluble status of marriage.”

It has also been forgotten that about half of all brides in Britain and North America were pregnant at their weddings in the 18th century (L. Stone, “Passionate Attachments in the West in Historical Perspective,” in K. Scott and Mr. Warren [eds.], Perspectives on Marriage: A Reader). According to Stone, “this tells us more about sexual customs than about passionate attachments: Sex began at the moment of engagement, and marriage in church came later, often triggered by the pregnancy.” This certainly could have been the case with Robert Eastes and Anne Woodward.

The children of Robert Eastes, and Anne Woodward are:

1. Matthew Eastes, baptized 11 June 1592 at Sholden, Kent, died as infant. He is likely buried in the church yard at Sholden.

It’s also likely that they lost a second child, between Matthew and Sylvester, given the 4 year birth span. Alternatively, another child could have been born but the birth record no longer in existence or baptized elsewhere.

2. Sylvester Eastes, baptized 26 September 1596 at Ringwould, Kent.

3. Alice Eastes, baptized 26 March 1597 at Ringwould, Kent. She married Thomas Beane, 28 October 1628 at Ringwould, Kent, and had children: Christopher (1628); Richard (1632) of St. Mary the Virgin, Dover, Kent; Mary (1636) of Great Mongeham, Kent; Sarah (1638) of Westminster, London; Judith (1642); and, Thomas (1643) of All Hallows Staining, London. Notably, her children were all baptized in different locations.

4. Matthew Eastes, mariner, born 1601, Ringwould, Kent, died 1621, buried 4 June 1621, St Leonard’s, Deal, Kent, he married Margaret Johnson, 23 November 1620, Deal, Kent. Margaret died and was buried 15 October 1622, St Leonard’s, Deal, Kent. Children: Martha (1621) of Deal, Kent, and William (1621-1687) of Ringwould, Kent.

5. Robert Eastes, Jr. was baptized 29 May 1603, Ringwould, Kent, he married Dorothy Wilson, 31 January 1634, Ringwould, Kent. Children: Robert (1635), Thomas (1636), Sylvester (1638), Sarah (1640), infant (1643) of Ringwould, Kent, Matthew (1645-1723) and Richard (1647-1737), both born at Dover, Kent and died in America. Matthew and Richard constitute the “Northern Estes” line in America. They settled in Strafford Co., NH and then moved on to Essex Co., MA. David Powell details this line on his website.

6. Thomas Eastes, baptized 2 June 1605 at Ringwould, Kent, died in 1671, at Ringwould, Kent. He married Joan Wilson, 21 November 1636, at Ringwould, Kent. Joan died 1672, at Walmer, Kent. Children: John (1642), John (1645), Joan (1645) and Robert (1647) of Ringwould, Kent.

7. Susan Eastes, baptized 30 October 1608 at Ringwould, Kent.

8. John Eastes, baptized 3 March 1610 at Ringwould, Kent, he spent the latter years of his life in poverty, living on parish assistance. John died in 1684, at Ripple, Kent. He married unknown, and had son John, born 1642 of Eastry, Kent.

9. Female Infant Eastes, born in 1616 at Ringwould, Kent, died at birth.

In 1601, when James I ascended the throne, he declared the war with Spain officially over and the people of Kent could relax a bit. However, the long years of tensions along the coast might have encouraged some folks to move a ways inland. Robert was reported to be a mariner, but the only record I have been able to find indicating his occupation was at his death and lists him only as a householder, meaning one who heads a house. However, given that Robert’s mother died when he was young, and his father was assuredly a fisherman, as well as his son Matthew, it’s likely that Robert was too.

From 1595 until their deaths in 1616 and 1630, respectively, Robert and Anne would count Ringwould as their home church. It’s very likely that they lived in very close proximity as well, as the various churches in the villages were only a couple of miles apart. Ringwould was less than a mile from the sea and a couple miles from Deal where the fishing fleet was centered. If Robert were fishing, it would not make much sense for him to move away from the area where fishing occurred. Ringwould was a farming area.

If you drew a circle half way between Ringwould and all of the other adjacent churches, that circle would certainly include Robert and Anne’s home and wouldn’t be more than a mile distant from Ringwould at any point.

In the satellite photo, above, St. Nicholas church is located by the C in Church Lane and the cemetery takes up the rest of the churchyard. The photo below is the church from the main road, take from about the location of the blue dot to the right of “A258” and looking over the field to the church and churchyard.

The small village of Ringwould lies on the A258, known as Dover Road, the main road between Dover and Deal, it has a population of about 350, this has remained roughly the same for the last 200 years, although the number of houses in the village has doubled in that period. Today Ringwould is a quiet village with a Pub, a Church and a village hall. The school moved to Kingsdown in about 1980 and the Post Office closed not long after. Today, there isn’t even a convenience store.

The village was first recorded more than 200 years before the Domesday survey, in an Anglo-Saxon Charter dated 861 AD under the name of Roedligwealda (the forest of Hredel’s people). The site of a Roman period farm has been identified close to the present Ripple windmill; which is in the parish, although metal detector finds and other relics which have been found, suggest that the area was populated well before the Roman invasion. The oldest coin ever found in England was discovered by a metal detectorist working close to Ringwould. It seems probable that the village was established sometime during the Anglo-Saxon period, probably in the 6th century AD, a thousand years before the Norman Conquest of 1066. In 1326, King Edward II granted a charter giving permission for a weekly market and an annual fair in Ringwould on the feast of St. Nicholas celebrated on December 6th each year.

By the late Norman period the timber Anglo-Saxon Church had been replaced by the present parish church which is thought to have been built about 1130. It has grown with the settlement and still contains a record of the alterations made through the centuries in its fabric.

The church originally had a wooden spire, but in 1627, the villagers petitioned the archdeacon to demolish the spire and replace it with a flint and brick tower. The villagers requested that they be allowed to keep the lead worth 28 pounds which would help offset the expenses anticipated to be 100 pounds to build the new tower. The new tower was to have pinnaces or ornaments, but today only the cupola remains. For many years, the year 1628, in iron figures, probably created in the forge just down the path, was affixed to the tower. There were originally 5 bells in the new tower, one original bell from the 1300s, 4 added in 1628, and a 6th added in 1957. Hence, the name of the local pub, Five Bells.

Anne Woodward Eastes would have been involved with the petition, although, being a woman, she may not have been allowed to sign. She would have watched the new tower being built, as it was three years before her death. During the construction, services went on as normal. There is an Estes marriage and christening during this time.

As late as the 1940’s Ringwould was still very much a manor village, with the squire, the Monins family, living in Ringwould House and a fair proportion of the village residents working on the manor property and living in houses owned by the manor. The Monins family is the historical manorial patron family beginning with Richard Monins in 1727, but it’s unclear who the earlier manorial family would have been. This is very interesting as it suggests that the Estes family in the 1600s would have likely been doing the same thing and very likely worked for the manorial family.

The following church records provide us with a glimpse of the events in the church most assuredly attended faithfully by our Estes family. Note that the transcribed records that I photographed at the church do not agree entirely with the records extracted by Estes researchers from original documents earlier, as reflected in the list of children given above. Roy Eastes in his book The Eastes-Estes Families of America – Our English Roots, stated that Donald Bowler utilized the Bishop’s returns. The records in the Ringwould church are from their own books, not duplicate copies sent to the Bishop. either set of records could certainly have omissions for various reasons.

September 26, 1596 – Silvester Estey, son of Robert, christened

Silvester is the son of Robert Estes who married Ann Woodward at Shoulden on December 2, 1591. Their first child, Matthew, was baptized at Shoulden in 1592. Silvester is their second child and the first record of an Estes in Ringwould except for the burial of Robert’s father, Sylvester, in 1579.

March 28, 1598 – Allice Estey daughter of Robert christened.

It looks like they lost two children here or the births aren’t recorded.

June 2, 1605 – Thomas Estis, son of Robert christened.

They may have lost a child here.

Oct 30, 1608 – Susas Estis, daughter of Robert christened.

March 3, 1610 – John Eastis, son of Robert christened.

And perhaps lost another child here.

Nov. 4, 1616 – Robert Eustace, householder buried.

Dec. 22, 1616 – daughter of Robert Eustace, not baptized, buried.

These two records, of Robert’s death and then just 6 weeks later, of Anne losing the child she was pregnant with when Robert died, are simply profoundly sad. I can see the grieving woman, with her children, ranging in age from 6 to 20, and heavily pregnant, standing in the churchyard beside the casket as they lowered it into the ground, burying her husband. A few weeks later, she would return to the same cemetery to bury her youngest child, just like she buried her oldest child years before. Life then was not easy, nor was it fair. My heart still breaks for her, almost 400 years later.

Anne did, however, live to see two of her children married and she would have certainly attended those weddings.

November 24, 1625 – Silvester Esties and Ellen Martin married

Silvester and Ellen would name their first child after Silvester’s deceased father, Robert.

Sept. 10, 1626 – Robert Esties, son of Selvester christened.

Silvester and Ellen’s second child was a daughter that they named after Silvester’s mother. She was, assuredly at the baptism of those children and it was most certainly a joyful day.

Nov. 25, 1627 – Anne Esties, daughter of Selvester christened.

October 20, 1628 – Thomas Beane and Alice Esties married.

Anne’s second child married, another joyful day of celebration.

May 31, 1629 – Selvester Esties, daughter of Selvester christened.

Note that Selvester is now a female in this generation. This is not the only female Sylvester in the Estes family.

March 20, 1630 – Susan Esties, daughter of Selvester christened.

May 18, 1630 – Anne Esties, widdowe, buried.

St. Nicholas Church at Ringwould, more than 800 years old, dating from about 1130, is near and dear to my heart. It is a smaller church than beautiful and majestic St. Leonard’s in Deal. It’s a country or manorial church in the vernacular of that day and time, meaning is was supported by the manorial family who owned the land. It reminds me in many ways of the simpler country church where I grew up. Of course, it was a very different time and place, but the cohesive bond formed by church members in a small church probably wasn’t any different then than now. St Nicholas, even today reflects a feeling of warmth and intimacy. You know that everyone knew everyone else and probably everything about everyone too. In 1578, the year before Sylvester Estes was buried in the churchyard, the church was recorded as having 60 communicants, meaning those taking Communion. By 1640, 60 years later and 10 years after Anne died, they had 170 communicants – so it was a growing community.

St. Nicholas Church at Ringwould, more than 800 years old, dating from about 1130, is near and dear to my heart. It is a smaller church than beautiful and majestic St. Leonard’s in Deal. It’s a country or manorial church in the vernacular of that day and time, meaning is was supported by the manorial family who owned the land. It reminds me in many ways of the simpler country church where I grew up. Of course, it was a very different time and place, but the cohesive bond formed by church members in a small church probably wasn’t any different then than now. St Nicholas, even today reflects a feeling of warmth and intimacy. You know that everyone knew everyone else and probably everything about everyone too. In 1578, the year before Sylvester Estes was buried in the churchyard, the church was recorded as having 60 communicants, meaning those taking Communion. By 1640, 60 years later and 10 years after Anne died, they had 170 communicants – so it was a growing community.

The church then was the center and focal point of the community. Important events occurred there, transactions took place on the porch of the church, and it was the center of the lives of the people, both religiously and socially. The church was expanded at least three times, as shown below.

The Victorian renovation in 1867-1869 was extensive and swept away much of the original interior of the church, including the box pews, pulpit, choir stalls and sadly, the original baptismal font. They also removed the “rendering” on the outside of the church and replaced it with flint facing. This drawing is before the renovations to the exterior.

The Victorian renovation in 1867-1869 was extensive and swept away much of the original interior of the church, including the box pews, pulpit, choir stalls and sadly, the original baptismal font. They also removed the “rendering” on the outside of the church and replaced it with flint facing. This drawing is before the renovations to the exterior.

The church in Ringwould was also physically at the center of the original village. Church Lane curves around the church and cemetery, the main road abutted the church lands and a path approached the church, just wide enough for a coffin carried by 2 men on either side.

This approach is from Church Lane.

In front of the church is one of two giant yew trees, remnants from Anglo-Saxon pagan days of worship, the hollow one being dated as 1300 years old, so a seedling in about the year 700, and a second one, below, 1000 years old. A Bronze age village is known to have existed here and Saxon graves were recorded nearby.

Two doors welcome visitors today. This looks to be the older door.

The green door is the second entryway and the one utilized today with a porch.

The old footpath, below, passes the forge before arriving at the church “gate.” This, of course, would have been the original way that the villagers arrived at the church.

This gate wasn’t present at that time, but it’s likely that some gate was to prevent the livestock from grazing in the churchyard.

They walked up this walkway, carrying gifts, children and sometimes, caskets. We are walking in the footsteps of generations.

The porch was added in the 1300s and was likely a very welcome addition. Some of the rites, such as baptism, started outside the church and had been open to the weather.

Walking around the end of the church to the side with the porch provides a beautiful view of the hand carved crosses on the roof.

The porch also includes a 12th century Mass Dial, used like a sun dial, before the advent of clocks so that the priest and others could tell the times of the several daily services.

There are several “Crusaders Crosses” well cut into the stonework fo the original main door frame. Legend has it that the Crusaders returning from the Holy Land would blunt their swords on the doors of the first church they saw. The last of the Crusades ended in 1291.

Entering the church through the porch, we see the very unique atmosphere found only in the seafaring communities near the waterfront in Kent.

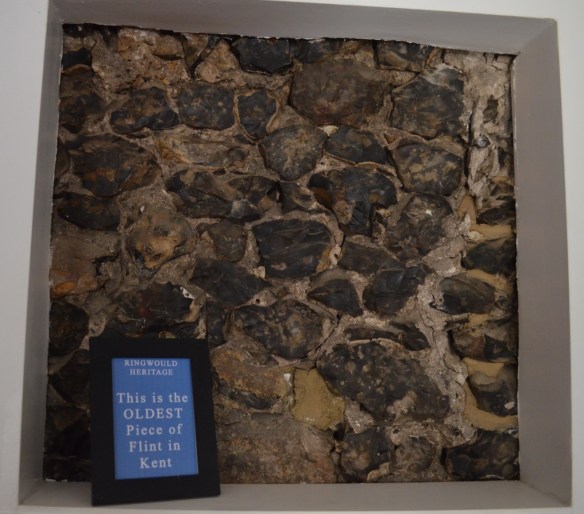

Flint was used routinely for churches in this part of England. In fact, there is a sign at the Five Bells Pub on the corner that says they have the “Oldest Flint in Kent.”

I’m not quite sure how they determined that this was older than the rest, but it’s just a block away from St. Nicholas Church. This would imply that this building is perhaps older than the church, or maybe simply reflects that the flint on the church was added in the 1800s. But, back to the church.

Entering the church, we see the stained glass windows in the chancel, where our ancestors would have watched the Catholic priests, then later the Protestant ministers, deliver the message, be it inspirational, damning or comforting.

Today, the pulpit is just outside of the chancel in the nave. These are not the original pews, but this is where our ancestors sat.

Looking to the left, we see the alcove where the organ is found today, but would have been originally a place where candles were lit in the Catholic church to saints.

Beautiful stained glass windows in Norman arches. This church was built in the 1300s, with renovations in 1638 when the tower was built.

And of course, the sedilia, the seats for the priests, carved into the walls. I looked for a piscina nearby but did not see one. It could have been behind something or removed during the Victorian renovations.

St. Nicholas has lots of small beautiful stained glass windows tucked into arches

Of course, a window and statue for St. Nicholas, the church’s patron Saint.

This beautiful tapestry hung in the church. The message of Madonna and child is universal in the Christian world. This is the church where Anne Woodward Estes raised her children after Robert’s passing in 1616, so the message of the Holy Mother would certainly have resonated with her.

The bapistry where our ancestor, Silvester, would have been baptized, as well as some of his children. Unfortunately, this bapistry is from the late 1800s.

Anne was buried in in the churchyard in 1630, preceded by her husband and unbaptized daughter in 1616. The fact that her daughter was unbaptized meant that the child was either stillborn or died very quickly after birth and was therefore not named. Later, there were at least three more Estes burials reflected in the records, none with stones that survive today.

Yes, we know that Anne, Robert and their unnamed daughter are here, in addition to Robert’s father, Sylvester, so let’s take a walk around the churchyard in the cemetery.

Many of the stones are quite aged, from the 1700s, and this church does not appear to have removed older stones.

The cemetery, or churchyard, is beautiful, it’s ancient trees speaking to the age of the bones and dust that lie here as well. There are likely burials here from at least the 1200s.

Tombstones weren’t utilized until the late 1600s, but I do wonder if people took mementos and left them when visiting the graves of their loved ones. Did Robert have an anchor on his grave or something from his line of work? Did Robert visit his father, Sylvester, the fisherman’s grave? Did Anne take flowers to put on her daughter’s grave that assuredly lay beside her husband? Were all of the Estes family buried together, or scattered about the churchyard?

This yew, as well as the second one, would both have been old trees by the time that Robert and Anne died. Did they stand in their shade. Did Sylvester play among these trees as he grew to adulthood? Did he court Ellen Martin here? Kiss her maybe?

These are the three windows in the chancel of the church with the yew in the side yard.

The beautiful stone cross visible above.

Graves not arranged, but scattered everyplace.

Most of these stones are illegible today.

I wonder if the vacant spots were known burial locations of ancestors and were intentionally avoided, or if they just haven’t been reused.

The oldest, hollow, yew.

I find this starkly beautiful and wonder if it was hollow when our ancestors lived here. If so, you can count on the fact that the kids played here. A hollow tree would have been unavoidably attractive to little boys!

A door bricked in and no longer in use on the back side.

I don’t know what the orange bubble on the photo is beside the yew tree, above. Some say dust on the camera lens, but others suggest that bubbles like this are spirits manifesting themselves. If that could possibly be true, we know whose spirit is here.

There are newer graves here, but they are off to the side.

View from the second yew. A woman we met at the church said that when she was a child, the men used the wood from the yew for arrows for archery practice. I’m guessing that was a very old tradition.

And of course, with all of these old English churches, there is always someone buried just outside the door.

We may not know where, but we know that the family rests here someplace, and we have visited them.

Anne was buried here in May 1630 after writing her will a month earlier. She would have been about 60 years old. Not old by today’s standards, but then the average life expectancy was about 37, although that was likely partly because of infant mortality. In other words, if you survived childhood, you might have lived beyond 37. For women, childbirth was extremely risky as well, but she survived all of those risks. She clearly had some warning that the grim reaper was about to visit because she had the opportunity to make a will. I wish the burial records told us why or how people died.

What record we do have of Anne’s will, reported by Donald Bowler who did the original research, says her will referred to 9 children. In the records above, we show 5 children living and “room” for four more. Were those children’s baptisms simply not recorded, or were they baptized in a different church? Perhaps the transcriptions are incomplete. We know one set of records is from the bishop’s copies and one is from the actual church records. Or, were the 9 children in her will actually 9 individuals, perhaps a combination of children and grandchildren? Without her will, we’ll never know.

Obtaining Robert’s DNA Without Digging Him Up

What we do know is that Robert and Ellen Woodward Eastes’ son, Silvester, from whom I descend, married Ellen Martin in this same church. Silvester had two sons, Abraham and Richard, and descendants of both lines have DNA tested.

Robert and Ellen also had son Matthew, who had two sons, William and John, who founded the Northern US Estes line. We have DNA results from both of these sons’ lines as well.

This means that Robert Estes is our oldest ancestor we can confirm genetically in the Estes line. If a male Estes, a direct descendant of one of the sons of Robert’s father, Sylvester, or grandfather, Nicholas, were to test, then we could confirm yet another generation or two up the tree – but today, we’re lucky to have Robert confirmed. That’s 12 generations for some of our DNA participants.

When a man has descendants who test through at least two different sons, we are able to “reconstruct” his Y DNA, for the most part, based on his descendants’ values.

In our case, we aren’t limited to two descendants, we have 25 proven descendants through 2 sons and 4 different grandsons.

What does this tell us about Robert’s DNA?

It gives us the ability to reconstruct Robert’s DNA values through a process called triangulation.

When the men from Robert’s 2 sons lines all match, we know, easily, the value of Robert’s DNA at those markers. It’s the same as both sons’ lines.

When it doesn’t match, then we have to look and see if we can figure out where the mutation took place in the various lines in question, and from that, if we can usually determine the oldest ancestral value of the marker in question.

The genealogy of Robert’s descendants looks roughly like the chart below.

*See footnote 2

This chart means that Robert and Anne Woodward Eastes had two sons who are represented in our testing, Sylvester and Matthew. Matthew had two sons, William and John, and today, several generations later, 10 to 12 to be exact, we have one proven descendant from each of those two sons whose DNA kit numbers are shown. Robert and Anne’s son Sylvester had two sons, Abraham and Richard, noted in green on the chart below. Richard’s descendant who DNA tested still lives in England, but Abraham was the immigrant to Virginia, and he has 22 kits with solidly proven descent to six of his eight sons. The other two sons have tentative (unproven) links, but I did not use their information in this study because they are unproven.

You can see on the chart above that of the first 18 markers, all except three match exactly, so we can easily fill in the values for all of those markers for Robert. Note that you can double click on the image to see a larger version.

Now, let’s look at the other three markers where mutations have occurred.

In Abraham’s case, I’m using a composite value created by using this same triangulation method. For the other’s we have only one kit from a descending line, so we are using that value.

The first marker with a discrepancy is 391.

Unfortunately, determining Robert’s original value of this marker, 10, or 12, or even possibly 11 if each line mutated in opposite directions, is impossible. Why? Because both of Sylvester’s descendants have a value of 12 and both of Matthew’s descendants have a value of 10. This means that we have confirmation back to those men, and the mutation likely took place in the generation between Robert and his sons, Sylvester and Matthew. To make things even more complex, some of Abraham’s descendants have a value of 11, but there are more values of 12 than of 11 in his son’s lines, so his composite has a value of 12. This marker may simply be very prone to mutation in the Estes family. If another of Robert’s sons’ descendants were to test, they could break the tie, but until then, we simply won’t know.

The second marker with a discrepancy is 439.

In this case, determining the value is possible, because even though there are three different values showing, 11, 12 and 13, one each of Sylvester’s and Matthew’s descendants have a value of 12, so Robert’s value is most likely 12 as well. Checking Abraham’s composite, it’s clearly a 12, so no issue there.

The third marker with a mutation is 447.

This call is easy, because three of the 4 descendants, including both sons Sylvester and Matthew have a value of 26, so the 25 is clearly the mutation. Therefore, Robert’s value has to be 26.

So Robert, who has been dead and buried in an unmarked grave since 1616, 398 years, can have his DNA values determined, and without digging him up! Not that we could do that anyway. His values are as shown below, except for marker 391 which could be either 10, 11 or 12.

Now, if I could just find someone who carries Anne Woodward’s mitochondrial DNA, I’d be ecstatic! Of course, that would have to be descended from her through all females to the current generation where it could be a man – and yes, in case you were wondering, there is a scholarship for anyone fitting that bill!

Footnotes:

[1] Before or After the Wedding by Adrian Thatcher at http://thewitness.org/archive/april2000/marriage.html

2. Since this article was written, a third son of Robert and Anne Woodward Eastes has been documented, through son Robert Eastye and Dorothy Wilson, their son Richard born 1647who married Elizabeth Beck and subsequently immigrated to the US. Richard died in 1737. The descendant’s results can be viewed as kit number 264340 in the Estes DNA project.

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- Family Tree DNA

- MyHeritage DNA only

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload

- AncestryDNA

- 23andMe Ancestry

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists for genealogy research

Discover more from DNAeXplained - Genetic Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Enjoyed this a lot. Terrific photos with illuminating narrative. I am showing Silvester Estes as my 13th ggf in my Ancestry.com tree.

You always include so much useful information in your posts, stuff we can use in the future. Thanks so much for all the research you do freely in our behalf.

Roberta, aren’t three STR mutations for the first 18 markers a lot for just 12 generations? I was under the impression that STRs don’t mutate quite that fast. I have several exact matches at 12 markers that aren’t even close when extended out to 67, and the MRCA on the closest match is assuredly before the Norman conquest. I’m not questioning the obvious family link, just the STR mutation rate.

Yes, you are right, Mark, it is high. That seems to be the theme of the Estes DNA.

Then I guess that just goes to show how variable the STR mutation rate can be from one line to another. I’d think that would call into question some of the software tools available for measuring MRCA from STRs.

The best that software tools can do is an average – which of course includes outliers in both directions. I only utilize those when I have absolutely no other information or alternative. And then, I’m glad to have them.

Pingback: Sylvester Estes (1596-c1647), Sometimes Churchwarden, 52 Ancestors #31 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Abraham Estes, (c 1647-1720), The Immigrant, 52 Ancestors #35 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Great information as always, Roberta. Looking forward to spending more time with it and also the links shown. Bob Guild, descendant of Abraham Estes, The Immigrant, a 7th Great Grandfather to me.

I love reading your posts! Trying to follow my Estes line. My ggf is Robert Calvin Estes, descendant of John Bacon Estes. Does that make John Bacon 7th generation to (Benjamin,Robert,Abraham,Sylvester,Robert Eastice)? Fascinating stuff here!

Pingback: Finding Moses Estes (1711-1787), 52 Ancestors #69 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Moses Estes (c 1742-1813), Distiller of Fine Brandy and Cyder, 52 Ancestors #72 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: What is a DNA Scholarship and How Do I Get One? | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy