Let’s begin this journey by disproving Hugh Benson’s birth.

He might have been the Hugh Benson born on September 5, 1653 to William Benson in Yorkshire. The timeframe fits, and so does the location for Catholics.

Transcribed; “Hugh Benson, sone to Wm. Benson, the 4 of September.” The year, “53” is recorded at right.

This record is attached to many trees, but it’s incorrect. How do we know that?

Further digging in this church’s records reveals that this child, Hugh Benson, was buried on November 7, 1653, so this is NOT our Hugh Benson unless he came back to life.

And no, there were not multiple Hugh Bensons born to William Benson in this same church, at least not that are indexed.

This is a reminder about getting excited and failing to check further. A name and place does not a match make, no matter how much we want that to be the case. I ws very disappointed, to put it mildly.

There are other Hugh Bensons born about this time in England, but we don’t know which one, if any of those, is ours.

Arrival

The first record we can attribute to our Hugh Benson is his arrival in Maryland which would have taken between two and four months onboard a ship, assuming nothing went wrong.

We know Hugh Benson was transported into the colony of Maryland on February 16, 1671 by Thomas Notley. He was apparently one of 53 “adventurers” and was free by 1682. The fact that Notley describes them as “adventurers” tells us that they weren’t convicts, political prisoners, petty thieves, or perhaps even common indentured servants. Researcher Kent Walker believes that this shipload of men were handpicked by the Catholic gentry because they were known and trusted.

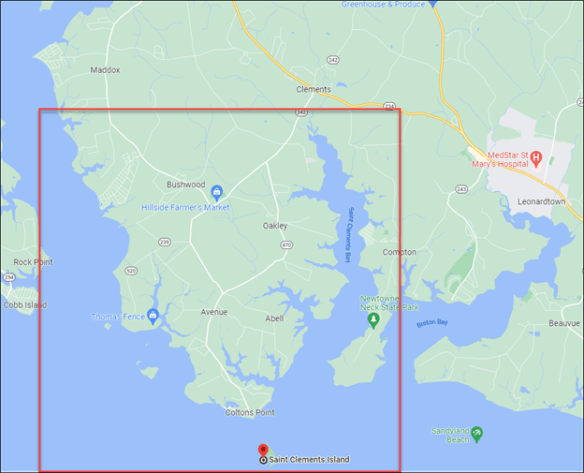

Many ships arrived at St. Clement’s Island at the entrance of St. Clement’s Bay, as did the first settlers in 1634. Blackistone Lighthouse marks the location, along with a cross, today marks the location in the St. Clement’s Island State Park.

While we don’t know the name of the ship that transported Hugh, the St. Mary’s Historic District created a full-sized working replica of the Dove, above, the smaller of two ships that arrived in March of 1634 with settlers, Jesuit missionaries, and indentured servants to establish what would become Maryland. The Calvert family was fulfilling their dream of establishing a safe haven for Catholics who were persecuted in England beginning in the mid-1500s during the rule of Henry VIII. Life as a Catholic became increasingly dangerous in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The larger ships looked something like this replica in Amsterdam

Confined on these ships for weeks, mostly below deck, sleeping like cordwood in rows of hammocks, passengers would have been anything but comfortable. I tried a hammock, and not only could I not get in, I barely got out. Let’s just say there was a lot of laughter.

I’m not even going to mention personal hygiene on these ships, because there wasn’t any.

If you were lucky, the water wasn’t contaminated, lasted the length of the voyage, and the food didn’t rot or become spoiled on the way.

Danger loomed everyplace.

The ships, the masts, something going wrong, weather, dysentery, typhoid, falling or being washed overboard, not to mention issues like chronic seasickness.

One had to really, REALLY want to make this journey, or maybe have no choice in the matter.

Some died, some traveled once and never again, but others make a life on the sea.

Thomas Notley, the man who transported Hugh Benson, was a Catholic planter, merchant, and attorney in St. Mary’s County. He was active as a Burgess beginning not long after his arrival in 1662. He lived in St. Clements Hundred, and in St. Mary’s City.

In 1663, Notley purchased 500 acres from Thomas Gerrard and then added another 1800 acres. He built Notley Hall, a manor about 2-3 miles south of what is today, Maddox, Maryland. This may well have been where Hugh Benson spent at least part, if not all of his indenture.

The archives of Maryland report that their council meetings on August 6, 1676 and January 1678 were held at Manahowick’s Neck, meaning Notley’s Manor. Hugh was likely there in 1676, as indentured servants weren’t generally freed for 7 years. During a full council meeting, Notley probably had all of his servants and enslaved people at the location where many people were gathered. Notley would have needed prodigious amounts of food, lodging, and personal services for his many guests.

You can get an idea of what this area looked like by viewing the photos from the Lower Notley Hall Farm event facility, here.

Notley died testate in 1679, with no children. In his estate, he had “11 male slaves, 8 female slaves, 2 male servants, 1 female servant, 10 undetermined slaves, 5 undetermined servants.”

Hugh Benson may have been one of those servants, depending on the length of time he had to serve for his transportation. The normal length of indentured servitude was 7 years, so he might have been freed in 1678. The length of time could have been more or less depending on the contract or specific circumstances.

Dr. Carr summarized her findings about Hugh in her work and reflects that Hugh was free by 1682.

What’s somewhat confusing is Hugh’s marriage and wife, Catherine, whose birth surname is unknown.

It wasn’t common practice for indentured men to marry before arrival. Indentured people generally weren’t allowed to marry during their servitude, either.

However, we know that Hugh had at least two children with his wife, Catherine, before his death in 1687.

Mary Benson was born to Hugh Benson and Catherine sometime after his 1671 immigration, probably between 1673 and 1680, in St. Clement’s Hundred.

It’s thanks to records relating to that daughter, Mary, that we know as much about Hugh Benson as we do.

St. Clement’s Hundred was defined as St. Clements Island and 5 miles into the mainland. St. Clements is where Thomas Notley lived as well as the colonial capital at St. Mary’s City.

This inset from a 1685 map shows the Pamunkey Indian land, Portabaco, Clements Bay and St. Clements Island, and then St. Marys City. Zachia Swamp, spelled Zachkia and noted by its Native name of Pamgayo played a huge role in the lives of the next generation of settlers.

What was going on at that time in Maryland, based on the few existing St. Clements manorial records?

September 1670 – We prsent That the Lord of the Mannor (Thomas Gerard) hath not provided a paire of Stocks, pillory, and Cucking Stoole. Ordered that these Instrumts of Justice be provided by the next Court by a generall contribution throughout the Manor

“Instruments of Justice”

Stocks and pillories were both installed in the public square.

Stocks, as opposed to the pillory, only restrained the legs, and while seated. Stocks were used as both punishment as well as restraint while the accused was awaiting trial. Often people were sentenced to more than a day confined in the stocks, so they would have to soil themselves.

Since part of the point was humiliation, passerbys were encouraged to do whatever came to mind. Fiendish boys would often remove the shoes of the person in the stocks and tickle their feet. Trash and other objects were thrown, and whipping occurred, sometimes to the bottoms of the bare feet.

These stocks remain in Belstone in Dartmoor, England, as a historical marker. Notice that there is no backrest.

A pillory restrains the hands and head while the victim is standing.

Here’s me in a replica pillory in Williamsburg.

Traditional pillories were often elevated on a platform for spectator sport and designed as a torture device. I couldn’t find any historical images that weren’t nauseating and I’m not going to describe what else was done to pilloried people. Humans can be unbelievably cruel and take such perverse pleasure in inflicting cruelty upon others, and watching. I’m amazed what crowds can be convinced to go along with sometimes.

I might be smiling in this photo, but trust me, no one who was there for more than about 5 minutes would have been smiling. If you relaxed your legs, you effectively hung yourself.

What offenses got you sentenced to time in the pillory in colonial America? Public intoxication, blasphemy, fortune telling, arson, and if you were enslaved, escaping or attempting to. The pillory was also a method of disabling someone while others abused, tortured, or murdered, them.

The third “instrument of justice,” the cuckolding stool was used to dunk offenders, primarily women, who were deemed disorderly or “too scoldy,” as indicated by this 1615 ballad:

Then was the Scold herself,

In a wheelbarrow brought,

Stripped naked to the smock,

As in that case she ought:

Neats tongues about her neck

Were hung in open show;

And thus unto the cucking stool

This famous scold did go.

Sadly, many women were immersed for so long that they drown. And yes, people watched for sport.

Eventually, dunking, with or without benefit of a chair, was a test for witchcraft. If you didn’t drown, you were deemed to be in league with the devil, and you were then killed. If you’re thinking to yourself that there was no “win” here, you’d be exactly right.

Yes, unfortunately, there were witchcraft trials in Maryland. Moll Dyer, who died about 1697, was reportedly chased from her home by local townspeople in the winter of 1697 in Leonard’s Town, Maryland, after being accused of witchcraft. It’s thought that Moll was actually a healer, but a flu epidemic during the winter of 1697 led to her being an easy mark for people looking for a scapegoat.

By Dougtone – https://www.flickr.com/photos/7327243@N05/8146403314/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=97671645

Moll was found a few days later, dead, frozen to a stone, now named the Moll Dyer’s rock. The rock was rediscovered and transported to the courthouse square several years ago.

You could be a Catholic in Maryland, but don’t even think about being a healer or, Heaven forbid, being “scoldy” or talking back to your husband. So, I wonder if scolding people for not going to church was acceptable. And what about scoldy men?

I think if I lived in early Maryland, I might just get dunked for even asking those questions out loud.

Everyday Life

Reading the transcribed documents in the Maryland archives is quite interesting, not just for witches, but to understand the drumbeat of everyday life.

For example, an October 28, 1672 list of residents, leaseholders, and freeholders shows within St. Clement’s Manor shows Thomas Notley, but not Hugh Benson, which of course, means that Hugh was a servant.

Citizens were mentioned or reprimanded for a variety of offenses in St. Clement’s Hundred, including

- keeping a tippling house

- a man’s dogs injuring another man’s hogs

- creating an affray and shedding blood

- annoying another by keeping hogs, a mare and foal

- selling drink without a license at unlawful rates

- reporting a stray horse

- not showing up for court

- unlawfully cutting timber

- killing a hogg but not sharing with the “lord of the manor”

The next peek we get into the life of Hugh Benson is in 1682, nearly a dozen years after his arrival, when his unnamed daughter is mentioned in the will of Collins Mackenzie.

The Maryland Calendar of wills provides us with this tantalizing tidbit.

Who was Collins Mackenzie, and why did he leave something to the unnamed daughter of Hugh Benson? That daughter had to be quite young. Is there a relationship with either Hugh or his wife, Catherine?

Whatever he left Benson’s daughter had to be tangible, because in Collin’s estate payments, nothing was paid to either Benson or Trench, which, it turns out, was actually James French who was also transported by Notley and indentured to Luke Gardiner on St. Clement’s Island.

There’s Richard Gardner, spelled elsewhere as Gardiner, again.

Because Mackenzie didn’t name a daughter, this also suggests that Hugh Benson only had one daughter, but since it was a nuncupative (spoken) will, he could simply have been very ill and near death.

If that unnamed daughter is Mary Benson, and we have to assume it is, she married Bowling Speake (of Charles County, MD) sometime in the early 1790s and they purchased land from the Gardiner family. How are these families interlaced?

According to a 1741 lawsuit, Richard Gardiner sold land to Hugh Benson of St. Mary’s County, MD, sometime after 1681.

Your Committee further find that the said Richard Crackborne by his Deed bearing date the 17th day of November 1681 did Bargain and Sell the said Tract of Land to Richard Gardiner of Saint Marys County in Fee Your Committee also find that Richard Gardiner and Elizabeth his Wife of St. Marys County aforesaid did Convey to Hugh Benson of the same County Planter 100 Acres Part of the said Tract in Fee [p. 273]

The following paragraph states the location.

Your Committee likewise find that Mary Speake is the reputed Daughter and Heiress at Law of Hugh Benson and that she intermarried (as it is said) with Bowling Speak of Charles County and that the said Bowling Speak and the said Mary his Wife, by their deed Bearing date the 31st of March 1739 did Convey the said Parcell of Land unto the Petitioner Thomas [Spalding] in Fee All which deeds appear to Your Committee to be duly Executed Your Committee further find by the Information of W James Swann a Member of your House that the Land called Crackbornes Purchase mentioned by the Petitioners to be Granted is of greater Value than that Part of the Land the Petitioners pray to be enabled to dispose of called Seamour Town or known by the name of Leonards Town.

Leonard’s Town, now Leonardtown, was part way between Notley Hall and St Mary’s City, so located just about perfectly. Given that Hugh Benson was Thomas Notley’s servant, he probably traveled this route many times between Notley Hall, the docks at Colton’s Point at St. Clement, and St. Mary’s City on behalf of his master. That path runs right through the center of Leondard’s Town. Perhaps Hugh spent the night there on his journey which would have been too distant for one day.

Leonardtown remains small, with quite a bit of land remaining undeveloped.

Leonardtown is charming and quaint today, with its old jail, now serving as a museum and visitor center still standing beside the courthouse. The original jail was apparently across the street.

The cannon in the garden outside is from the original ship, the Ark, one of two that transported the first settlers to Maryland in 1634.

The early bayside settlements like Leonard’s Town were ports, with towns established dockside to enable loading, unloading, and transacting business.

Hugh Benson was a planter, meaning a farmer in the vernacular of the day.

By Sarah Stierch – Flickr: St. Mary’s City, Maryland, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13157964

Historical St. Mary’s City has reconstructed a typical 17th-century planter’s house based on their findings in more than 200 archaeological digs. The home of Hugh and his family probably looked very much like this, with an outside kitchen.

Or, if Hugh was a little more well-do-do, perhaps he built a home with fireplaces, 4 rooms, and two partial stories like 1700s-era St. Mary’s Manor West.

Or, maybe their home looked more like Resurrection Manor, built as early as 1660, but now demolished. Library of Congress photos, here.

This internal photo was taken after Resurrection Manor had survived for nearly 300 years. Fireplaces heated homes which were quite small by comparison to today’s structures. Many, if not most, residences had outside kitchens, but Katherine may have cooked in a fireplace like this, with a grate, cauldron and pothooks, especially in the winter.

By Kathleen Tyler Conklin – Flickr: Leonard Calvert in the State House, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32277068

A period actor playing the role of Leonard Calvert at the colonial statehouse in St. Mary’s City gives us a glimpse into how the people Hugh interacted with would have dressed.

Hugh, of course, was probably dressed in much less opulent attire.

When in St. Mary’s on business for or with Thomas Notley, Hugh may well have worshipped in the Catholic Church built in 1667, reconstructed today.

The original settlers purchased land from the Piscataway Indians with whom they lived and traded peacefully for many years. The Indians befriended and helped the early colonists, being eager to learn more about their advanced methods and metal tools, like guns which made hunting much easier.

I found listings for three Testamentary Proceedings involving Hugh Benson although I have not examined the folios:

- 1682 – St. Mary’s Liber 12B, folio 309

- 1687 – St. Mary’s Liber 13, folio 514 (his estate filed)

- 1687 – St. Mary’s Liber 14, folio 43

Hugh Benson died in 1687 as a relatively young man, under 40, and probably suddenly, given that he had no will. What happened? Was there an accident?

On August 19, 1687, Katherine renounced administration of his estate to Richard Gardiner, who died not long thereafter in England. Gardiner was a fellow Catholic and Burgess.

In Gardiner’s estate proceedings, payment for a debt was received from Hugh Benson. Of course, that could have been an old debt, or given that the settlement was in 1696, that Hugh Benson could have been Hugh’s son.

The second to last mention of Hugh Benson was in 1694, although it could have been retrospectively:

Act for payment and assessing the publick charges of this province Acts of 1694 ch 32: Tobacco is paid: to Hugh Benson two hundred and Seaventy

There is a Hugh Benson who died in Stafford County, VA, unmarried, in November of 1699. There appear to be two Hugh Bensons in Stafford County during this time, as one was noted as a runaway from the service of John Doxsey in 1702.

Hugh Benson leaves us with several mysteries.

Katherine, then a widow, had at least one small child, Mary, to raise, and possibly more.

Katherine Remarries

Catherine or Katherine, widow of Hugh Benson, must have married Thomas Cooper, born around 1650, almost immediately after Hugh’s death. She would have been about 35 years old.

She had at least two more children with Cooper and possibly three.

Katherine was deceased 28 years later, by 1715, when Thomas Cooper made his will. She wasn’t named, and Thomas left all of his property to sons Thomas and Richard Cooper, both real and personal, jointly and equally.

Seems pretty straightforward, right?

Well, this is where things get complicated.

Who are Thomas Spalding and Catherine?

Thomas Cooper, Jr. appears to have been the oldest child. He married Mary Riley about 1712-1713, so he would probably have been born in the 1680s.

When Thomas Cooper Jr. died in 1722, he left, “To cousin — Cooper, 310 A. of “Crackbourn’s Purchase,” now owned with bro. Richard.” Also, “To dau. Katherine, personalty and all lands except dwell. plan. — during life of wife; at her decease, to pass to dau. afsd. She dying without issue, to cousin Thomas and hrs.” I think that 310acres should be 210 acres, but that’s not relevant to this discussion.

Is the Catherine married to Thomas Spalding the daughter of Thomas Cooper Jr., meaning the granddaughter of Hugh Benson’s wife, Katherine? It certainly appears so. Note the mention, above of Crackbourn’s Purchase.

Catherine Cooper and Thomas Spalding appear to own the original 200 acres (or 210 acres) of Crackbourn’s Purchase in 1741.

By the Committee appointed to enquire into the Facts contained in the Petition of Thomas Spalding and Catherine his Wife June the 6. 1741

Your Committee find on Inspecting the Papers of the Petitioners that the Land called Crackbornes Purchase containing 200 Acres was Granted on the 24th day of October Anno Domini 1659 unto Richard Crackborne Assignee of Walter Peak and Peter Mills Assignees of Paul Simpson in Fee. Your Committee further find that the said Richard Crackborne by his Deed bearing date the 17th day of November 1681 did Bargain and Sell the said Tract of Land to Richard Gardiner of Saint Marys County in Fee Your Committee also find that Richard Gardiner and Elizabeth his Wife of St Marys County aforesaid did Convey to Hugh Benson of the same County Planter 100 Acres Part of the said Tract in Fee [p. 273] Your Committee likewise find that Mary Speake is the reputed Daughter and Heiress at Law of Hugh Benson and that she intermarried (as it is said) with Bowling Speak of Charles County and that the said Bowling Speak and the said Mary his Wife, by their deed Bearing date the 31st of March 1739 did Convey the said Parcell of Land unto the Petitioner Thomas in Fee All which deeds appear to Your Committee to be duly Executed Your Committee further find by the Information of W James Swann a Member of your House that the Land called Crackbornes Purchase mentioned by the Petitioners to be Granted is of greater Value than that Part of the Land the Petitioners pray to be enabled to dispose of called Seamour Town or known by the name of Leonards Town.

Does this suggest that Hugh’s widow, Catherine married her neighbor, Thomas Cooper, who literally lived next door on Crackborne’s Purchase? Meaning that Crackborne’s Purchase, divided at one time into two pieces, has now been reunited?

It certainly looks that way.

Catherine’s daughter Mary Benson who married Bowling Speak sold that tract of land to Catherine’s granddaughter, Katherine, through her deceased son, Thomas Cooper Jr.

Did you get that? It was a mouthful. I had to draw this out, above.

The St. Francis Xavier Cemetery

This also suggests quite strongly that Hugh Benson, Catherine, Thomas Cooper, and probably Thomas Cooper Jr. are all buried together here in the original St. Francis Xavier Cemetery on Newtowne Neck Road, where the original Catholic church was located.

Hugh Benson and Katherine’s daughter, Mary Benson, was born around 1675. Given that Hugh didn’t die until 1687, they assuredly had at least 6 more children, if not more. Those children would have been laid to rest here too, hopefully near their parents’ eternal watch.

The Chesapeake was never far away.

The cemetery is only 400 or 500 feet from the Bay, on either side, bordered by Saint Clements Bay to the left, and Breton Bay to the right. The present-day church, which, along with the restored manor house, originally dated from 1731, is about half a mile south.

The Chesapeake, her moods, her ports, estuaries, swamps and swamp-fevers shaped the lives of the immigrant, Hugh Benson and his wife, Catherine.

The brave and hearty souls who pulled up stakes and left the known for the unknown set the stage for the next many generations of descendants.

Life in Leonard’s Town

My friend, Maree found luscious details in the book, Origins of Clements-Spalding and Allied Families of Maryland and Kentucky.

In this excerpt, we verify that Thomas Spalding married Catharine Cooper, the child of Thomas Cooper, and by inference, his wife Catherine, who was the widow of Hugh Benson.

Thomas Cooper had willed his entire estate to his daughter, Catherine, named for her mother, of course.

However, Catherine Cooper wasn’t her mother’s only child or her only daughter. Mary Benson was Catherine Cooper’s half-sister, the child of Hugh Benson and Catherine. Mary Benson married Bowling Speake, and she too had to convey her portion of Crackburn’s Purchase.

Crackburn was where the mill was located, and where the town of Leonard’s Town, now Leonardtown, was laid out, which ties back to the 1739 deed where Bowling and Mary conveyed that land to Thomas Spalding, of course.

That 1741 court action literally says, “…Part of the Land the Petitioners pray to be enabled to dispose of called Seamour Town or known by the name of Leonards Town.” Mary Benson and her husband Bowling Speake had owned part of what would become Leonard’s Town, thanks to her father, Hugh Benson, who obtained that land about 1681ish.

The history of Leonardtown tells us that Leonard’s Town, an important port, began in the 1650s as “Newtown” or “Newtown Hundred,” but began being called Leonard’s Town shortly thereafter in honor of Leonard Calvert.

In the early years, “court” was held in various private homes in the area, one of which was possibly Hugh Benson’s, given that he owned part of the town.

In 1708, twenty-one years after Hugh Benson died, but seven years before Catherine’s second husband, Thomas Cooper died, a designated courthouse was ordered to be established, and Leonard’s Town was renamed Seymour Town in honor of the then-current governor of Maryland. However, two decades later, in 1728, the name reverted, and Leonard’s Town became the location of official business within the colony. Unfortunately, the St. Mary’s County courthouse burned in 1831, destroying the valuable records within, which is why the paucity of records today. No deeds, no marriage records, nothing.

In 1708, the Mayor of St. Mary’s City also ordered that 50 acres of land at the head of Britton’s Bay be divided into 100 lots, including one for the courthouse. This officially became Seymour Town, then Leonardtown and appears to be, at least in part, the land occupied and mentioned in the Bowling Speake and Mary Benson Speake 1739 deed to Thomas Spalding and Catherine.

Thank goodness that transaction was referred for evaluation because otherwise, we would never have known any of this.

A walking tour of Leonardtown is available, here.

Of course, I can’t discern acreage from this map, but we can see the courthouse location in the center of town. The courthouse was supposed to be on one lot, and lots would have been about half an acre each.

The mill mentioned would have probably been located on Town Run.

Or maybe the mill was on McIntosh Run literally on the other border of Leonardtown.

A small branch runs right through the western side of Leonardtown.

McIntosh Run is where McIntosh Park is located today. I’m guessing it’s a park because it floods. With the original deeds burned in that courthouse fire, there’s no way of really knowing exactly which land Hugh Benson owned.

William Spalding’s 1741 will, he left to his son, Benedict, a tenement of land called Mill Land on which my Water Mill stands.” He also left his “Watermill” to his wife and sons with a lot of land in Leonard’s Town. Judging from this, the mill was someplace within the town limits.

It was here, someplace here, that Hugh Benson lived with Catherine. Their 100 acres was twice the size of the town, and probably somehow abutted it, including part of the town itself.

Given that Hugh was noted as being from St. Clements, I suspect that his land might have been between Breton Bay, meaning Leonardtown, and Saint Clements Bay. We know they attended church just north of Newtowne Neck State Park.

It looks like present-day Maryland 243, Newtowne Neck Road, was the road out of Leonardtown, white, bordered in red above, to the west, so let’s take a drive. It’s 3 miles to Compton and 5 miles to the end of the road.

At one point, just outside town, the road runs right alongside McIntosh Run and crosses a branch.

Most of this area remains heavily treed, swampy, or both, but Society Hill Road splits off of Newtowne Road about halfway to Compton, and you can see the Bay from the end of the road there.

Hugh and Katherine would have glimpsed the bay every time they traveled this road to church.

Higher, farmable land is polka-dotted along the way, carved out of the woodlands.

Generally, the road, in the center of the peninsula, or “neck” as it’s called in the local vernacular, is the highest elevation.

It’s clear why the economy here was focused on trade and ports, not agriculture except for occasional corn fields, a rare orchard, and interspersed patches of tobacco. Animals, mostly hogs, grazed freely in the woodlands.

No matter where you were, the saltwater bay was never far away.

Fresh, non-brackish water had to be at a premium. Settlers needed to be far enough inland to live on a freshwater stream, and not in a swamp, but still close to the port.

There were probably few good options, and the best locations would have been snatched up first by the wealthy proprietors. It’s no wonder that mortality was so high. Yet, this was the land of opportunity, better than the oppression in England if you were Catholic or another “non-conformist” religion.

The Remaining Questions

Of course, there are many questions that remain, but a few stand out.

- Did Hugh and Catherine Benson have two children, Mary and Hugh? Is the Hugh Benson mentioned in 1694 and 1696 their son, Hugh? If so, he would have had to have been born before 1673, which is just after Hugh Benson immigrated and while he was still an indentured servant.

That’s possible, especially if he arrived married, but it’s unlikely. Is there more to this story?

- Are either of the two Hugh Bensons in Virginia the son of Hugh and Catherine? If so, what happened to that child’s land holding given that Hugh died intestate? Why wasn’t a guardian appointed for the child or children? Or did those records burn in the 1831 fire? Was his land relinquished before or when/if he died in Virginia?

- Did Catherine have more than one surviving child with Thomas Cooper?

- According to Thomas Cooper’s will, he had two sons, Thomas Cooper (Jr.) and Richard Cooper. Was Richard also the son of Catherine, or was Thomas married previously? I don’t see anything to indicate that Thomas Cooper Sr. had a previous marriage.

Dr. Carr estimates Richard Cooper’s birth at 1693.

- Did Catherine, Hugh Benson’s widow, and Thomas Cooper have a third child, a daughter named Elizabeth who married James Wheatley? If so, it appears that Wheatley died relatively young and they had no children, unless Elizabeth remarried and disappeared from the records.

If Elizabeth Cooper who married James Wheatley was Katherine’s daughter, are there any descendants living today through all females to the current generation, which can be male? Those living people carry Catherine’s mitochondrial DNA. If that’s you, please reach out. I have a free DNA testing scholarship for you.

If you have answers, any information, or descend from Elizabeth Cooper and James Wheatley, I’d certainly love to hear from you!

Oh yes, and there’s one last burning question. Who was Catherine, wife of Hugh Benson and Thomas Cooper?

_____________________________________________________________

Follow DNAexplain on Facebook, here or follow me on Twitter, here.

Share the Love!

You’re always welcome to forward articles or links to friends and share on social media.

If you haven’t already subscribed (it’s free,) you can receive an email whenever I publish by clicking the “follow” button on the main blog page, here.

You Can Help Keep This Blog Free

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Uploads

- FamilyTreeDNA – Y, mitochondrial and autosomal DNA testing

- MyHeritage DNA – Autosomal DNA test

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload – Upload your DNA file from other vendors free

- AncestryDNA – Autosomal DNA test

- 23andMe Ancestry – Autosomal DNA only, no Health

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

Genealogy Products and Services

- MyHeritage FREE Tree Builder – Genealogy software for your computer

- MyHeritage Subscription with Free Trial

- Legacy Family Tree Webinars – Genealogy and DNA classes, subscription-based, some free

- Legacy Family Tree Software – Genealogy software for your computer

- Newspapers.com – Search newspapers for your ancestors

- NewspaperArchive – Search different newspapers for your ancestors

My Book

- DNA for Native American Genealogy – by Roberta Estes, for those ordering the e-book from anyplace, or paperback within the United States

- DNA for Native American Genealogy – for those ordering the paperback outside the US

Genealogy Books

- Genealogical.com – Lots of wonderful genealogy research books

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists – Professional genealogy research

Discover more from DNAeXplained - Genetic Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Roberta, I greatly enjoyed reading another of your 52 Ancestors. Thank you.

I always like to go to the original to see what the abstracts leave out. The unnamed daughter of Hugh Benson received a heifer from the nuncupative will of Collins McKensie/McKensye [not with a “z” as in the MD Calendar of Wills.] Also the name is clearly written as James French. There is also added information that Collins died at the house of Mr. Richard Gardiner [as spelled in the document.]

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C914-J9HW-X

The full list of names claimed by Mr. Thomas Notley may be seen in Maryland Patents 16:411 [image 212] at:

https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/stagserm/sm1/sm2/000000/000019/pdf/mdsa_sm2_19.pdf

Note that he claimed transportation for them on 14 February 1671, not that they were transported on that date, or even all at the same time. Land was often claimed years after transportation. The document does not call them “adventurers,” so the source of when (or if) Notley called them “adventurers” as listed by Kent Walker is unknown.

Thank you so much for these links. I tried to find the list of the people Notley transported to see if there might be some hint there but could not find the list. Hats off to you.

Rick, is there an index someplace I’m anaware of? I have three other people who were transported who are candidates to be his wife and I found them on the Maryland Land and Property site, but I need to be able to find something about them on the film – like hopefully – where they were transported into. Thanks.

http://earlysettlers.msa.maryland.gov/

contains the information from Skordas, as well as the supplement of additional records by Gibb. Those will give you the patent book and folio/page number for any person listed.

The Maryland State Archives is not the easiest place to navigate. I have added direct links to a lot of important records on my page:

http://fzsaunders.com/links.html

Once you have a patent book and page number, use the link labeled “Maryland Patents” on my page. Under the appropriate book click on “links” on the MSA page.

Thank you so very much. I’ll check soon.