Which Johann Michael Kirsch, wife Anna Margaretha, was the father of Elias Nicolaus Kirsch born in the beautiful little village of Fussgoenheim, Germany on May 6, 1733?

That’s the million-dollar question!

When I began this journey, we didn’t know that there were three different Johann Michael Kirschs that were candidates to be the father of Elias Nicolaus, nor that all three men were married to women named Anna Margaretha with no surname.

I mean, this was a tiny village, estimated to be 150-200 people total in 1720, or 30-40 families – not a city – so what are the chances that we would encounter this level of same-name confusion?

Most genealogical puzzles become easier as one obtains additional information. Not this one. Every new piece of information simply complicated the original question.

I wanted to pull my hair out. Even Tom, my trusty friend, was ready to throw in the towel from time to time. But thankfully, that’s not Tom, and he didn’t, viewing Johann Michael Kirsch as a challenge instead. Neither Tom nor Christoph bailed on me, and it’s a good thing because this would NEVER have been solved without the combined information and resources of both of them and several other people over the decades.

This is arguably the most difficult genealogical puzzle I’ve ever faced.

Just this week, Tom found the almost impossibly elusive nail that sealed the deal. I’ll share the answer after we work through the process, because our path of discovery may be beneficial to you as well. Additionally, I don’t want to waste any of the information we gathered that pertains to other Kirsch family members. Anyone who hits the Johann Michael Kirsch wall will need this.

Building Blocks

First, I need to express my gratitude.

Over the years:

- Tom and Christoph searched out, found, and translated innumerable documents – and I mean probably hundreds. Several years ago, Tom told me that solving this one would require reading and translating every Kirsch record in Fussgoenheim, and it would take a lifetime. I would never have asked him to do that, but alas, he wasn’t going to let Johann Michael Kirsch get the best of him. As it turns out, not only did it require reading every Kirsch record in Fussgoenheim but in other locations as well, PLUS records of other families besides Kirsch.

- My cousin Marliese in the 1940s sent wonderful letters and photos of the ancestral Kirsch home in Fussgoenheim to her Kirsch relatives in Aurora, Indiana, descendants of my ancestors who immigrated in the 1850s. Marliese’s daughter corresponded with me years later. I’ve written several articles about my Kirsch ancestors and finding their paths, here. Those paths were quite the forked road in many cases.

- Another 2 cousins, Irene and Joyce, long deceased, wrote letters in the 1970s and 1980s mentioning a German man, Walter Schnebel, who had provided some Kirsch information that has turned out to be quite accurate. That was long before the days of the internet, email, or sourcing genealogy, and as they aged, their letters stopped, leaving unanswered questions hanging. Not to mention, I had no idea how to find Walter.

- My blog follower, and now friend, Noél, took a detour on her vacation and actually found the original Kirsch home in Fussgoenheim, based on location work I did from the photos Marliese sent and Google maps. You can read that article here. The day I received those photos is one I’ll never forget. This was AMAZING!!! I am so grateful!

- Walter Schnebel researched and compiled information for decades about Fussgoenheim families and planned to publish a book, but unfortunately, he died in October 2018. Walter grew up next door to the Kirsch home in Fussgoenheim, and of course, was related as well.

- Blog follower William lives nearby in Germany and reached out to Walter’s family, obtaining a spreadsheet of Walter’s Kirsch family research and very kindly shared with me.

Walter’s research notes were invaluable, but his sources were not always listed. I’m sure those would have been in his book.

Walter had assigned my Elias Nicolaus Kirsch to one of the three Johann Michael Kirsch’s but never provided information as to why. As it turned out, Walter was right, and one simple note as to why he assigned Elias to that specific Johann Michael would have saved me (and Tom and Christoph) years of frustration trying to retrace Walter’s steps. By the way, those steps ultimately led to a different village altogether to locate that elusive proof. I’m not even sure that Walter found those same records. Having said that, trying to retrace Walter’s steps has provided me with the opportunity to get to know Fussgoenheim and her families much better.

During this process, I composed theories about the various relationships, and what information suggested which Johann Michael Kirsch was the father of my Elias Nicolaus. Tom and Christoph would review my theories and poke holes in them – often finding new records to add to our pile of evidence. We make an amazing team!!!

Proof, however, was maddeningly elusive – that is – until just recently.

The Earliest Records

Unfortunately, Fussgoenheim church records are limited and incomplete. I think Tom said they are the worst record set he has ever dealt with, and that’s saying something coming from a retired German genealogist.

- Baptisms: 1726-1798 and 1816-1839

- Marriages: 1727-1768 and 1816-1839

- Deaths: 1733-1775 and 1816-1839

While death records reportedly began in 1733, truth be told, they are nonexistent for many of those years entirely, especially early years, and spotty during other times. In other words, the absence of a record doesn’t imply the absence of the person.

I’ve wondered why some of these records are so sparse, and I did find a hint or two. In one record I discovered, it was mentioned that the residents were, or weren’t, paying for building a Lutheran church in the early 1730s. Given that they already had a church, why would they need to build another one? There were never two.

The answer may lay on this map titled “The Conquest of the Left Rhine Territories by France” that shows a military field camp near, at or in Fussgoenheim in August 1734, during the War of Polish Succession. Battle lines were drawn directly through the neighboring village of Mutterstadt.

There some script in the front of the 1733 church book that might explain this situation. I have vague memories of Elke, my translator back in the 1980s, discovering some text about the residents escaping over the Rhine for some time, and eventually, returning, but I can’t recall if it was the Mutterstadt or Fussgoenheim church books. This warfare might well explain both a lack of complete records during that timeframe, the absence of earlier records, and the need to rebuild a church.

The church itself dates from before 1728. Fussgoenheim’s history indicates that the village had been entirely Protestant since 1728. Christoph found information that states there are three remaining stones in the churchyard.

Christoph found information about two of the three old gravestones: There is one from 1605 for a son of Elias Roschel and one from 1606 for the wife of Elias Roschel. Elias Roschel is thought to have been the first Lutheran pastor in Fussgoenheim. Of course, this dates the existance of the Lutheran church to at least this time, albeit in an earlier building.

I would love to have interior photos of this quaint little church where my ancestors were baptized.

Early Generations of Kirschs

The earliest record of the Kirsch family in Fussgoenheim is that of Jerg Kirsch who married in Dürkheim in 1650 and is noted in other records as the co-lessee of the Josten estate in Fussgoenheim.

Jerg Kirsch, a nickname for Johann Georg, is the progenitor of the Kirsch family in Fussgoenheim.

Since church records don’t begin until long after Jerg’s children were born, the records of his children had to be assembled from later and scarce sources, such as births, marriages, deaths, and baptisms that identified people by their parents.

Jerg’s children were, in brief:

- Johann Jacob Kirsch born about 1655 and died before 1723, married Maria Catharina, surname unknown

- Daniel Kirsch born about 1660, died before 1723

- Johannes Kirsch born about 1665 and died in 1738, in Ellerstadt, never married

- Andreas born in 1666 and died in 1734, lived in Ellerstadt and Oggersheim, married Anna Barbara, surname unknown

- Johann Michael Kirsch, the Judge, and referred to as “the eldest” when he died, born in 1668 and died in 1743, married Anna Margaretha Spanier – he had a son Johann Michael

- Johann Michael Kirsch, the Baker, born about 1705 and died after 1753, married first to Anna Margaretha, surname unknown, married second to Anna Margaretha Wohlfahrt in 1739

- Johann Wilhelm Kirsch born about 1760, died before 1723, lived in Oggersheim

- Johann Adam Kirsch born in 1677 and died before 1740, first married the daughter of Adam Greulich and married second to Anna Maria Koob – he also had a son Johann Michael

- Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor, born about 1700, died between 1757 and October 1759, married first to Anna Margaretha, between surname unknown, who died in 1738, second to Maria Magdalena Michet in 1739

Here we see the three candidate Johann Michael Kirschs living in Fussgoenheim in 1733 when Elias Nicolaus was born.

I feel compelled to point out that we didn’t know any of this when we embarked on this journey, and none of it, not one iota, was easy to reassemble.

1743 and 1744

1743 and 1744 were watershed years in Fussgoenheim for our Kirsch family, as well as for the rest of the residents.

Fussgoenheim was a small village comprised of the upper village and lower village. Upper and lower refer to elevation, not north and south, and they are reversed from what you would expect, with under being the north side. The church was the dividing line, and the village was controlled historically by two different lords.

Christoph purchased a book about the history of Fussgoenhiem, written in German, and summarizes the following:

One of the strange stories about Fussgoenheim is that the town has been divided into two parts for centuries – ruled and owned by different lords. It has two parts, >Oberdorf< (upper village) and >Unterdorf< (lower village). The Lutheran church in the town center represented the border between the two parts. In 1728, the family von Hallberg acquired the upper village, later on around 1730, also the lower village.

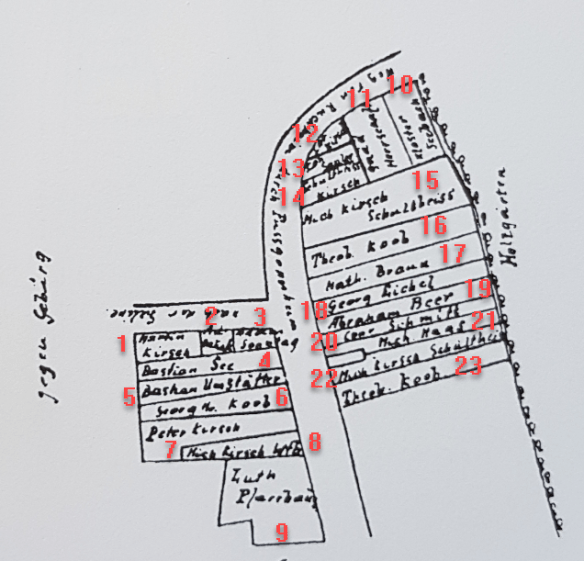

The upper village, above, was actually to the south of the lower village, below. The Lutheran church is the dividing line, and just below the church is the residence of William Kirsch, the only Kirsch to live on this side of town. It looks like there are a total of 10 households. On the right side of the road, the Hallberg castle was built about 1740, but wasn’t shown on this map.

The lower village is north of the upper village. You can see the Lutheran church parsonage on this map, just north of the church. On the same side of the road, we see 8 properties, and across the road, in the bend, we see 14 properties.

Those 14 properties include 6 that can be attributed to Kirsch men, as follows:

- Michael Kirsch, Schultheiss, which means mayor – three properties on the right-hand side

- Martin Kirsch, red arrow upper left

- Peter Kirsch, red arrow center left

- Michael Kirsch’s widow, who we know is Anna Margaretha Spanier. Her son is Peter Kirsch.

The green arrows are:

- Center left – may be another Kirsch male, beside Martin, but I can’t read clearly – could be Andreas

- Upper right on bend – clearly a Kirsch surname, but can’t read the first name

Johann Michael Kirsch, the eldest, not the elder, died in 1743, suggesting that there were, in fact, more than 2 Johann Michael Kirschs living in Fussgoenheim at that time.

We know from other records that in 1743, there was a Johann Michael Kirsch the Mayor and Johann Michael Kirsch the Baker, who were cousins, but we don’t know where the Baker lives. He could live in one of the properties of his clearly better-off cousin, the Mayor.

I numbered the residences, hoping to be able to read the names and correlate with other records.

The surnames on the 1743 maps are difficult to read, but looking at Ancestry for the indexed Fussgoenheim church records for 1740-1743, I find the following 63 surnames which I attempted to match with names/locations on the map. Bolded names are found on a partial list of individuals who refused to sign the land register – a story of bravery we’ll get to in a minute.

| Surnames | 1743 Map Location | 1743 Map Location | 1743 Map Location | 1743 Map Location | 1743 Map Location | 1743 Map Location |

| Ach | ||||||

| Andre | ||||||

| Bechmann/Beckman | ||||||

| Beer | 19 – Abraham Beet | |||||

| Benick | ||||||

| Bern | ||||||

| Borstler | ||||||

| Braun | 16 – Math Braun | |||||

| Brinck | ||||||

| Busch | ||||||

| Ebert | ||||||

| Eichecker | ||||||

| Eigel | 18 – Georg Eichel | |||||

| Freymanns | ||||||

| Gifft/Gitt/Giff/Geff | ||||||

| Haas | 21 – Michael Haas | |||||

| Hahn/Hohn | ||||||

| Hartmann | ||||||

| Hauck | 2- Hauk? | 31 – Wilh Hauck | 33 – And? Hauck | |||

| Henick | ||||||

| Herberich/Hernerich | ||||||

| Hunds | ||||||

| Hundsrucker | ||||||

| Kirsch | 1 – Martin Kirsch | 7 – Peter Kirsch | 8 – widow of Michael Kirsch | 12 – ? Kirsch | 14, 15, 22 – Michael Kirsch Mayor | 24 – William Kirsch |

| Klingler | ||||||

| Kob/Koob | 6 – George Koob | 16, 23 – Theob Koob | ||||

| Krauss | ||||||

| Krausshaar | ||||||

| Lang | ||||||

| Lanzer | ||||||

| Loien | ||||||

| Low | ||||||

| Marti | ||||||

| Metthert | ||||||

| Meyer | ||||||

| Molstert | ||||||

| Nenonistin | ||||||

| Ritthaler | ||||||

| Rob | ||||||

| Rudolphi | ||||||

| Ruger | ||||||

| Rusch | ||||||

| Sahler | 13 – Sahler? | |||||

| Schaffer | ||||||

| Schimbeno/Schimbeneau | ||||||

| Schimbers | ||||||

| Schlaag | ||||||

| Schmuter | ||||||

| Schrnun | ||||||

| Schuler | ||||||

| Schulzer | ||||||

| Schumacher | ||||||

| Schweitzer/Schweizer | ||||||

| Sonntag/Stuntag | 3 – Seantag | |||||

| Spanger | ||||||

| Sterh | ||||||

| Stroh | ||||||

| Strop | ||||||

| Stros | ||||||

| Tab | ||||||

| Uger | ||||||

| Uller/Uler | ||||||

| Wiedemann | ||||||

| Wier | ||||||

| Map Names/Locations Not in Church Records | ||||||

| 4 – Bastian See | ||||||

| 5 – Bastian Umslatter? | ||||||

| 9 – Lutheran church & parsonage | ||||||

| 10 – Seebach | ||||||

| 11 – Herrschmat? | ||||||

| 20 – ? Schmitt | ||||||

| 25 – Saalee? | ||||||

| 26 – ? | ||||||

| 27 – ? | ||||||

| 28 – Seel | ||||||

| 29 – ? | ||||||

| 30 – Bingemann | ||||||

| 32 – Elspermann | ||||||

A few surnames are found only once or twice in the records, some may be misspelled duplicates, but many surnames are found repeatedly. This makes me wonder where all of these people lived since their homes are not on the map.

I think I have the answer, but I’m not positive. Based on the history I can glean, I think the 1743 map has to do with private land ownership and the Hallberg family acquiring the two halves of the village in 1728 and 1730. If this is the case, then serfs, or people without land that was privately owned would not be shown on the map.

However, a brochure from Fussgoenheim written in the 1980s tells us that Hallberg’s resurvey redivided the area and built new roads. In doing so, some fields were now disconnected from their previous owners and were considered abandoned. As you can see from maps, farmer’s fields extended behind their homes. Those resurveyed disconnected fields were considered abandoned and Hallberg confiscated them for his own.

Conversely, there seem to be several surnames on the maps, but not in the Lutheran church records, at least not for those years. This is somewhat confusing, unless those people were older and there were no births are deaths during this timeframe. There’s also another possibility.

There is a mention of a Jewish community in Fussgoenheim as early as 1684, associated with the Jewish community in Ruchheim, or, maybe some of those surnames were associated with the Hallberg castle and dynasty, which was Catholic. Either would explain why we don’t find those surnames in the Lutheran Church records.

Looking at the existing church records and residences, both, it’s quite evident that the Kirsch family was the most prevalent in the village. Ironic since they had only lived in the village since about 1650, so about 90 years by that time. Still, that’s roughly 3 generations, but with large families, the progenitor could and did have a lot of descendants.

Even today, the village has grown, but the original property lines haven’t changed a lot from that 1743 map.

It’s interesting that you can see the same layout of the properties and lands that correlate to earlier maps.

You can see the Protestant church at the green arrow, the Kirsch home at the red arrow, and the Koob home with the gold arrow, exactly as Marliese described in the 1940s with the information provided by her grandmother Marie Kirsch who was born in 1871. These locations also match the 1743 map with the Kirsch and Koob families living in the exact same locations.

The house to the left of the “X,” above, is the Kirsch property, and the house directly under the “O” is the Koob home.

The following map shows the entire historical village of Fussgoenheim, with arrows pointing to the Kirsch home, the church, and the Hallberg castle, at lower right.

Of course, I’m left wondering if the 1743 map is the redrawn Hallberg map that caused such an uproar? I suspect so, meaning that the original map would have shown more private ownership. Is that why Michael Kirsch, the Baker, is absent, perchance? The citizens disagreed with the Hallberg map vehemently.

I’m very grateful for the 1743 map, regardless, because, in 1744, things changed dramatically.

1744

All Hell broke loose in 1744.

One Johann Michael Kirsch was dead. The remaining two Johann Michael Kirschs both, BOTH, were expelled from Fussgoenheim in 1744.

As Tom said to me a few years back, “Your guy got kicked out. I wonder what he did.”

Yea, me too!

Christoph provides some history:

After the von Hallberg family acquired the balance of the village in 1730, they seem to have been quite reckless in pressing out money and goods from the town people. Ruthless to the extent that the people opposed them. It should also be noted that all town people were Lutheran, while the ruling family von Halberg was Catholic – a great divide in those days.

Shortly after Baron von Halberg took over the rule, he decided in 1729 to have a new town plan recorded and to divide up the lots differently than before. Doing so, he seems to have cheated here and there and taken land for himself. At least this is what the town people accused him of, and the town`s court members refused to sign the new plan. Von Hallberg`s reaction was to expel these court members along with their families (in total: 15 families with 70 persons) from Fussgoenheim. The expelled settled in nearby Ellerstadt and appealed to the Imperial Chamber Court (>Reichskammergericht<) who ruled in 1750 that von Hallberg had to take back the expelled families and return them their land. The judgment was repeated by the Imperial Chamber Court in 1753. Hence seemingly von Hallberg just ignored the court ruling at first.

Note that the 1743 map only shows a total of 32 properties, so roughly half of those families were expelled. The under-village, to the north that includes the Kirsch and Koob interrelated families includes only 22 parcels of land owned by 19 different people. Mayor Kirsch owns (at least) three and Theop. Koob owns two.

Christoph continues:

In 1752 even the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire accused the town people of not paying their taxes to von Hallberg. The emperor urged von Hallberg to bring to justice the Mayor Kirsch and other town people. In this case, a high court decided against the town people and threatened them with the military, in case they would continue to not pay their taxes.

In the following years, the town people seemingly paid their taxes and just tried, again and again, to appeal to the court.

In September 1744, Jakob Hallberg died, which may have given the Fussgoenheimers some sliver of hope, soon to be dashed. His son inherited Fussgoenheim and the Hallberg dynasty lasted until the conquest of the Palatinate by the French in the 1890s.

An automatically translated portion of the Fussgoenheim town history (with minor edits for clarify) goes on to say:

One of the accusations leveled against Hallberg was that he had confiscated inherited property and community property. At that time, in the course of a property renovation, ownerless properties fell to the onlord – this was the so-called right to the “bona vacamia”.

In 1729 Hallberg had a property renovation carried out in Fußgönheim which is understandable insofar as he, as the new lord of the village, needed to get an overview of the ownership and legal relationships in the village and the resulting obligations for charges and services.

According to the land survey, the district of Fußgönheim comprised at that time 2,869 3/4 acres of land, 95 % of which were in the possession of clergymen or of certain masters or were communal property. Only 146 3/4 acres were owned by private persons. According to the renovation protocol, Hallberg has 386 acres of land in its own property. This could be the so-called “abandoned property” confiscated by him.

Wow, it looks like he confiscated 2.64 times the amount he left in private ownership. No wonder the residents were angry – especially those residents who had owned those 386 acres. This averages 4.59 acres per privately owned parcel as judged by Hallberg, and suggests that the original parcels averaged 16.65 acres. That’s quite a difference, especially if you’re trying to earn a living from the land.

Furthermore, if you look at the Under village, and the Upper village, you’ll notice quickly that the Under village is where the majority of the Lutheran church records match village surnames, and those parcels appear visually much smaller than the parcels allocated to the upper village across from the Hallberg castle, where many of the surnames are not found in the church records and are likely Catholic. It would appear that Hallberg also favored his friends and fellow Catholics.

Hallberg is also said to have confiscated hereditary property if the families have no inheritance or had not used their annual ground rent. Hallberg obviously interpreted the right of the “bona vacanria” very strictly, for his own benefit and to the detriment of the villagers. A 1750 expert opinion of the KurpHilz council of Schnerr confirmed Hallberg in principle that he had the right to confiscate ownerless property, “but whether in such a large excess as he had…a legal investigation would have to clarify.”

Hallberg was widely disliked by the Fussgoenheimers, with good reason. The translation continues:

During the field survey, Hallberg had redirected field paths and redivided the winnings. He had land given to him for the abandoned goods he had confiscated in the best profits.

By reducing the size of the rods, he had achieved that when surveying the individual acres of “leftovers” which were left over, which he is also said to have illegally taken.

No wonder the citizens were furious.

The village’s court officers therefore refused to sign the land book which had been created by Hallberg. Hallberg reacted to this by expelling the court officers and their families – a total of 15 families with 70 persons – from the village.

It’s interesting to note that the average family size was 4.67 persons, two of whom would have been the parents. Evidence of high childhood mortality is recorded within the church books.

Another tidbit about Fussgoenheim tells us that Schimbeneau, Herberich, Schuster, Theobald Koob, and Schultheiß (Mayor) Kirsch are the individuals who refused to sign the 1729 land register, resulting in their 1744 expulsion.

The persons concerned, who had in the meantime settled in Ellerstadt and accepted serfdom there, filed a complaint against this action. In 1750 the Reich Chamber Court in Wetzlar sentenced Hallberg to take back the expelled persons and return their property to them. The order was repeated in 1753, which suggests that Hallberg had defied the judgment. He stated that he tolerated in his village no stranger to serfdom.

Serfdom was a form of semi-slavery in which a person was tied to the land is a form of indentured servitude from which peasants could not escape. Serfs traditionally could not even marry without the approval of their Lord (not church Lord, feudal Lord) and had minimal control of their own lives. It would appear that Hallberg’s goal was to reduce everyone in his village to that status whom he could then entirely control.

Note that this 1753 order is probably the reason for the “1753 accounting” notes that we see in Walter Schnebel’s information. Unfortunately, I don’t have that actual document.

Another dispute arose over the community’s sheep pasture, the lease of which had brought the community an annual income of 100 gulden. Hallberg claimed the pasture for himself in a letter of feudal title dated 30 July 1728. The residents, on the other hand, referred to their “old rights.” The dispute ended in 1733 with a compromise: Hallberg got the sheep pasture under the condition that not too many sheep graze on it.

Another accusation against Hallberg was that he had transferred the tithe income of middle-class farms. In Fußgönheim there were three bourgeois courts which had a share of the tithe income.

Hallberg withdrew this income on the grounds that the owners refused to contribute to the costs of building the Lutheran Church.

The lucrative “Weinschank,” i.e. the right to run a wine tavern, was auctioned by Hallberg for 120 gulden annually; before that it was free.

“Wine tavern,” I love it! I know that my family was involved. I surely would like to know who ran the wine tavern. Too bad that’s not noted on the map.

We know from other sources that the present-day Lutheran church was either built or renovated about the time the new church books began in 1726. I can’t help but wonder if the original church burned, along with the records.

Hallberg also introduced a new levy of 15 Malcer oats to be paid annually to his magistrate.

In the face of massive resistance from the community, Hallberg had the village sized(?) for two months by a corporal and six men. When the inhabitants refused to pay 71 guldens every 114 days for their accommodation, he had 7 cattle, 1 cow, clothes, guns, and household goods taken away without further ado and auctioned them off in Worms.

The community then turned to the Oberlehengericht in 1745. The court ordered Hallberg to return the confiscated objects under threat of a 500 gulden fine. In addition, he had to give an account before the fiefdom court about his actions.

Equally bitter resistance was met by von Hallberg’s increase of the treasury with an annual levy on real property. According to this, each landowner had to pay a guilder for 10 acres of land.

Hallberg countered the resistance of the inhabitants by leaving the village for 10 days with 57 grenadiers.

Grenadiers were a type of large, strong elite soldier. Think “Navy Seal” or “Green Beret” today. Hallberg was clearly trying to intimidate the villagers. This was an extremely high soldier to villager ratio.

During that time, 28 horses and cows were confiscated in the village, which Hallberg then sold at an auction. The Fußgönheim court was put under arrest for 14 days and then expelled from the village.

Woo boy.

Another lucrative source of income was created by Hallberg with the introduction of a tababvaage system, where all tobacco sold in the village had to be weighed against a weighing fee. This provided him with benefits in addition to the usual tobacco tithes of 70-80 gulden per man per year.

In 1752, the emperor even reprimanded the villagers because they refused to pay the levies imposed on them. He called on Mayor Kirsch and other local leaders because of fanned resistance and riots to be held accountable. In 1757, the highest court of the Reich, the Reichshofrar, ruled against the Fußgönheimers: It obliged them to pay frontage money, unpaid money and the fees for the tobacco scales and threatened military intervention by the troops of the Upper Rhine District in the event of any violation.

Hallberg wrote that he was quite happy that proceedings had been instituted against Mayor Kirsch, and that no leniency should be shown towards him.

There is clearly a life-long animosity between these two families. Michael Kirsch must have hated everything Hallberg, but he would not cave.

A similar statement by the Hallberg official of Bissing: “The farmers have so far been whitewashed unruly heads and stiff flails, so it does not do them any harm now if you make them feel the effect of a permitted revenge. The previous executions will have dazed their overconfidence in something, but now they have to crawl to Creutz.”

The old language and translation didn’t work perfectly, but I think the word revenge portrays the sentiment. Hallberg wanted to punish Johann Michael Kirsch as an example meant to keep other unruly villagers in line who dared to think they should retain their own land or expect justice.

In time, however, the people of Fußgönheim came to terms with the Hallberg dominion.

In other words, Hallberg wore them down. Their resistance, along with hope, seemed to wane, especially after the death of Mayor Kirsch. Who wanted to sign up to be the target of the Hallberg empire? Everyone saw what happened to him and his family.

A list from the year 1785 shows that all once-disputed duties and taxes had been paid. The people of Fußgönheim no longer offered open resistance, but tried to enforce their rights through the courts: in 1770 they asked the imperial chancellery whether their files had been mislaid, since nothing had happened in respect of their claims for 24 years now (since 1746), – a trial of such a length was not possible in the complicated proceedings before the Reichshofrar. But that was nothing out of the ordinary.

Obviously, the court was never going to address the grievances of the villagers after 24 years of intentional silence. That’s in essence a generation, and many of the originally “wronged” people had since died. I’m sure that’s what Hallberg was counting on – and eventually – everyone just accepted and forgot and he achieved exactly what he wanted – their lands, in perpetuity.

He had subdued the Fussgoenheim village families, but they must have hated him.

The original landowners were all-in though, willing to risk it all, to sacrifice for justice by participating in civil disobedience and “riots,” whatever that means in this context. These families were irreversibly committed – even being kicked out of Fussgoenheim, in exile, as peasants, serfs in Ellerstadt, which seems to have lasted for about a decade. Still, they didn’t capitulate.

Even in 1753, after returning to Fussgoenheim, which was a victory in and of itself, it appears that they were never able to fully regain what was rightfully theirs – meaning the land before the 1729 Hallberg reorganization of the village.

It may be difficult to fight city hall, but it appears impossible to win against the House of Hallberg, a hereditary Lordship. The Hallbergs simply had too much power.

Return to Fussgoenheim

We know that the two Johann Michael Kirschs, plus Johann Jacob Kirsch, adult married son of the Mayor are three of the families who were evicted to Ellerstadt. We don’t know who all of the other families were, but I’m wagering they were some of, or a majority of, the families who were listed as owning land on that 1743 map. There were only 17 landowners who also appeared in the church records, in total. This might suggest that some of the other landowners were not Protestant – implying Catholic which means that Hallberg would likely have treated them differently. There were a total of 32 parcels of owned land, and 29 landowners, with many of the families in the upper village having no church records. The upper village was the portion on the south side of the village, south of the Lutheran church, directly across from the Hallberg castle that included a small Catholic church.

Both Johann Michael Kirschs returned to Fussgoenheim about 1753 when an accounting took place that involved several grandchildren of the original Jerg Kirsch. Johann Jacob Kirsch, the Mayor’s son who had been evicted, had children baptized in Ellerstadt as late as 1759. It appears that some of the Kirsch family members settled into Ellerstadt and never returned.

However, Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor, was forcibly removed from his position after returning to Fussgoenheim. Hallberg dismissed Johann Michael Kirsch as mayor in 1757 by decree of cassation from the highest court of appeals.

Clearly, Johann Michael Kirsch hadn’t gone and didn’t go willingly, probably kicking and screaming every inch of the way – beginning about 1729/1730 when Hallberg acquired the entire village and began his resurvey. Johann Michael would have been about 29 or 30 then, about 43 or 44 when he was evicted, about 53 when he returned, and about 57 when he was stripped of his title and responsibilities as Mayor – serving as a thorn in Hallberg’s side the entire time.

Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor was dead by October 1759. This final chapter of his life must have been incredibly stressful. I wonder if it hastened his demise. In fact, I can’t help but wonder how he died.

This never-ending battle defined Johann Michael Kirsch’s life.

Johann Michael spent literally half of his life, most of his entire adult life, in a life-and-death struggle with the Hallberg dynasty, first father, then son, trying to thwart their attempts to take the Kirsch family lands, and in his capacity as Mayor, that of other Fussgoenheim residents as well.

The classic good versus evil battle. Except this time, good didn’t entirely win. But then again, neither did evil.

The Goal

My goal is to figure out which Johann Michael Kirsch is the father of Elias Nicolaus Kirsch born in 1733.

All three Johann Michael Kirschs have wives named Anna Margaretha in 1733. How frustrating is this!

- Three men with exactly the same name.

- All 3 related to each other.

- All three with wives named Anna Margaretha with no known surname.

- In the same small village.

That should be illegal!

Elias Nicolaus’s baptism record doesn’t provide a surname for his mother, nor an occupation for his father, but we do have some scattered threads of evidence.

We have a family grouped spreadsheet from Walter Schnebel, with some sources, and a translation spreadsheet of Fussgoenheim church records assembled by Tom. We have historical records provided by Christoph.

Let’s take a look at how we sorted through this mess.

Sifting Through the Evidence

One Johann Michael Kirsch, designated as “the eldest,” died in 1743 at the age of 83, so born in 1661. It’s possible that he had a child in 1733, at the age of 73, but not as likely as the two other younger Michaels.

Tom’s translation:

“On 12 January 1743 in the morning between 3 and 4 o’clock died in the Lord, Johann Michael Kirsch, the Eldest [!], after 15 weeks of sickbed, and was buried on the 13th of the same month. First Sunday after Epiphany. Age: 82 [years].”

As Tom mentioned, the Eldest suggests at least two younger men by the same name, the Elder and the Younger.

| Name | Birth | Death | Job | Parents | Spouse |

| (Johann) Michael d. Ä. | 1668 | 12.01.1743 | Ackerer † Gerichtsmann – judge | Jerg u. Margaretha Koch | Anna Margaretha Spanier (als Witwe in Rechnungslegung 1753 erwähnt) – Anna Margaretha Spanier (mentioned as a widow in accounting 1753) |

Walter Schnebel’s spreadsheet states that Anna Margaretha Spanier was mentioned in 1753 as the widow in the accounting. Given that the other two Johann Michael Kirschs are living, she has to be the widow of Johann Michael Kirsch, the Judge, who died in 1743.

Michael Kirsch Sr.

There are two births recorded with the designation of Michael “Sr.”, one in February of 1738 to Michael Sr. and Anna Margaretha, daughter, Anna Margaretha, godparents Johann Georg Eigel, the court member and wife Margaretha nee Ritthaler.

| Father | Wife | Child | Godparents | |

| 1738-02-10 | Kirsch Johann Michael Sr | Anna Margaretha | Anna Margaretha | Eigel Johann Georg the court member and wife Margaretha nee Ritthaler |

The second birth attributed to Michael Sr. occurred March 23, 1741, daughter Maria Catharina, godparents Johann Jacob Kirsch, citizen here and wife Maria Catharina NN (no name). Note that Johann Jacob Kirsch appears to be Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor’s sibling. This also fits given that several of these births had important government people as godparents.

| Father | Wife | Child | Godparents | |

| 1741-03-23 | Kirsch Johann Michael Sr | Anna Margaretha | Maria Catharina | Kirsch, Johann Jacob citizen here and wife Maria Catharina NN |

This second birth attributed to Michael Sr. occurred after the 1743 death, so this birth is clearly NOT the Judge.

Elias Nicolaus Kirsch – Known Ancestor

Johann Michael Kirsch with no wife’s surname had son Elias Nicolaus Kirsch in May of 1733. This is my ancestor. Godparents were Elias Nicolaus Specht from Dürkheim, and wife. I can find nothing on Ancestry or FamilySearch about the identity of Elias Nicolaus Specht, or his wife.

| Father | Wife | Child | Godparents | |

| 1733-05-06 | Kirsch, Johann Michael | Anna Margaretha | Elias Nicolaus | Specht Elias Nicolaus from Durckheim and wife |

Given this birth date, the next child would have been born to this couple about 18-24 months later, and the previous child, if it lived, about 18-24 months prior.

Two Michael’s

Births to the two Johann Michael Kirschs who would have been having children during this timeframe are shown in the following table. Michael who died in 1743 is excluded because I am, perhaps wrongly, assuming that he was no longer having children at 65 years of age (in 1726 when baptism records begin) and then older. His known children were born between 1700 and 1717.

I created a chart compiling information about each birth, assigning relationships where possible.

Legend:

- White rows – I don’t have any idea which Michael, the Mayor or the Baker, to assign this birth to. There may be conflicting snippets of information.

- Peach rows – either known to be the Baker, or probably the Baker due to the witnesses. Some are from Walter’s spreadsheet whom he attributed to Michael the Baker, but I don’t know why.

- Green – definitely not my Michael

- Grey – the Mayor or probably the Mayor. One thing that makes sense is that the Baker would have stayed closer to home, baking daily, while the Mayor was cultivating influential friendships in other villages. This shows in the godparent selections.

- Yellow – mine or important evidence about mine

Note 1: The Mayor’s second wife. They married in 1739, after Elias was born, so unfortunately this has nothing to do with Elias’s mother.

Note 2: Walter Schnebel shows the following for Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor:

| Name | Birth | Death | Job | Parents | Spouse | Notes |

| Johann Michael sen. | um 1700 | vor 1759 | 1750 Schultheiß, Erbbeständer (heiress) in Fgh. u. Ellerstadt | Johann Adam u. Anna Maria Koob | 1. Anna Margaretha N.N. (†17.12.38); 2. Maria Magdalena Michet (*26.10.00 Als †6.1.84 Als, verw. Saar, T.v. Johann Michael u. Eva Ramsauer) ~ 23.6.39 | in Rechnungslegung 1753 erfasst; v. Halberg 1757 durch Kassasionsdekret als Schultheiß abgesetzt; um 1744 mit seinem Vetter Michael (Bäcker) ausgewiesen, hatte 1753, 2 Söhne u. 4 Töchter in Ellerstadt, Deepl Translation: recorded in 1753; v. Halberg dismissed as mayor in 1757 by decree of cassation; around 1744 shown with his cousin Michael (baker), had 2 sons and 4 daughters in Ellerstadt in 1753 |

I can’t decipher all of Walter’s German notes under spouse, except to understand that Anna Margaretha died in December of 1738 and Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor, remarried. Additionally, his cousin was Michael (born circa 1705), the Baker, which suggests common grandparents, or further back depending on how the word cousin was used, was also expelled to Ellerstadt in 1744.

Walter shows Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor’s siblings as:

- Johann Wilhelm Kirsch, born 1706, married Maria Catharina Spanier in November 1727. Note that in 1730, Johann Michael Kirsch and his wife Anna Margaretha were witnesses for his child named Johann Michael.

- Johann Jacob Kirsch, born about 1710, married Maria Catharina. Note: Maria Catharina N.N., Wtw.v.Joh.Nicolaus Schumacher,Schneidermstr.aus Fgh.) ~ 9.2.40 Also note: Tz. 1730

- Maria Catharina Kirsch, born about 1715, died Sept 1778 Als, married Johannes Neumann (aus Gronau) ~ 5.5.1739 Fgh

- Johann Peter Kirsch, born 1716, died before 1760, married 1. Maria Barbara Spanier (†6.7.37) ~ 8.5.1736; 2.Maria Magd.Gutermann ~ 18.2.38 Gönn; Anna Elisabetha Löw ~ 19.1.1740. There is a note that he is in Rechnungslegunt (accounting) in 1753. In 1737, Johann Jacob Kirsch, living in Dürkheim, witnessed the baptism of a child for Johann Peter.

Here are Walter’s notes for Johann Michael Kirsch, the Baker:

| Name | Birth | Death | Job | Parents | Spouse | Notes |

| Johann Michael | um 1705 | Bäcker | Johann Michael u. Anna Margaretha Spanier | 1. Anna Margaretha N.N.; 2. Anna Margaretha Wohlfahrt ~ 1.12.1739 | mit seinem Vetter, Schultheiß Joh. Michael 1744 nach Ell ausgewiesen, hatte dort 1753 1 Sohn u. 1 Tochter; in Rechnungslegung 1753 – with his cousin, Schultheiß Joh. Michael was expelled to Ell in 1744, and had 1 son there in 1753. 1 daughter; in Accounting 1753 – Deepl translation: with his cousin, Sheriff Joh. Michael expelled to Ell in 1744, had 1 son and 1 daughter there in 1753; in accounting 1753 – with his cousin, Sheriff Joh. Michael was expelled to Ell in 1744, and had 1 son there in 1753. 1 daughter; in accounting 1753 |

Walter shows the siblings of Johann Michael Kirsch, the Baker, as:

- Johann Daniel Kirsch, born circa 1700, died 1737, married Anna Margaretha Storck (2. Ehe Valentin Schweitzer ~22.12.39).

- Johann Jacob Kirsch, born December 1693 in Fussgoenheim, died 1762 Dürkheim, married Susanna Magdalena Müller (*1710 DÜW, T.v. Johann Georg) ~ 2.5.30 Dürkheim.

- Johann George Kirsch, born circa 1704, Schmiedemstr., Gerichtsmann (court man translation), married Anna Maria Margaretha Hartmann ~ 27.01.1728. Also in (accounting) in 1753, Note that in 1732, Johann Michael and his wife, Anna Margaretha were witnesses for this man’s child named Johann Michael.

- Johann Nichlaus “Nickel” Kirsch, born circa 1710, married Anna Maria Scheuer (aus Großniedesheim) ~ before 1731 ?, Note: in accounting in 1753; Tz. 1766 bei Enkelin See: Note that in February 1742 Michael Kirsch and Anna Maria were godparents for a child born. This suggests that this is the Baker, not the Mayor.

- Anna Catharine Kirsch, born 1717, confirmed 1730, but nothing more found.

Who’s Connected to Dürkheim?

We find connections in the godparents’ records to Dürkheim, in particular, the godparents of Elias Nicolaus. Is the connection to Dürkheim through the wives of one or the other Johann Michael Kirschs?

Who is the wife of Elias Nicolaus Specht? Would that provide a clue? Or his mother, perhaps?

Who were the wives of the Johann Michael Kirschs? Don’t I wish I knew.

Michael, the Baker, was the son of Johann Michael Kirsch who died in 1743 and Anna Margaretha Spanier.

Michael, the Mayor, was the son of Johann Adam Kirsch and Anna Maria Koob.

What are the Dürkheim connections?

- Both Johann Michael Kirsch (died 1743) and Johann Adam Kirsch were the son of Jerg Kirsch and Margaretha Koch, apparently from Dürkheim. Here is Walter’s note about her: Margaretha Koch (*um 1630, T.v. Stephan u. N.N.) married 09.09.1650 in Dürkheim

- Johann Michael, the Baker’s brother, Johann Jacob died in Dürkheim by 1762.

- Johann Jacob Kirsch, the brother of Johann Michael, the Mayor, lived in Dürkheim in 1737.

- Child of Johann Wilhelm Kirsch and Anna Maria in 1739 – godparents of child Johann Adam Hoffmann, butcher and wife Anna Maria of Dürkheim. Johann Wilhelm is the of Johann Adam Kirsch and Anna Maria Koob, brother of the Mayor.

The Dürkheim connection appears to stem from Margaretha Koch originally. Furthermore, this is where Jerg Kirsch and Margaretha was married, so the Kirsch line could also be from Dürkheim. So, the Dürkheim connection is not through one of the wives of one of the Johann Michael Kirschs, providing us with no further clues. This was a red herring.

Kirsch Children and Siblings

My next tactic.

I am hopeful that by making a chart looking at naming patterns that we can discern a useful pattern and maybe a few hints. Elias Nicolaus is not as common as other names, like Johannes.

I’ve assigned people with question marks to columns based on what I think, or Walter thinks.

Keep in mind that the same child’s name could be a result of the name of the godparents, not because of an intentional naming after someone. Wouldn’t it be nice if Elias Nicolaus’s children all lined up with the children of one of the Johann Michael Kirschs? Let’s see.

- ? means uncertainly assigned

Unfortunately, we don’t have all the records for the children of Elias Nicolaus, and the ones we do have are inconclusive in terms of naming patterns.

The naming patterns don’t provide us with any additional hints either. Rats!

Who Were Elias Nicolaus Kirsch’s Parents?

Based on the above data, here’s what we know.

- The first name of all 3 wives of the Michael Kirschs in 1733 was Anna Margaretha.

- The widow, Anna Margaretha, of Michael Kirsch who died in 1743 (born 1661), was mentioned in the 1753 accounting. He is unlikely to be the father of Elias Nicholas born in 1733. If she is his only wife, she would have been about age 45 in 1717, so certainly not having another child in 1733.

- Both younger Michael Kirsch’s, who were cousins, remarried, both after 1733 when Elias Nicholas was born. Their second wives are irrelevant to this equation, although both are widely assigned as his mother by some genealogists, especially in public trees.

- The surname of Anna Margaretha, the first wife of Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor, remains unknown, but he remarried to Maria Magdalena Michet on June 23, 1739. At least she had a different first name.

Tom’s translation:

Marriage: the 23rd of June 1739, the Ehrengracht? Herr Johann Michael Kirsch from here mayor of the area governed by von Hallberg with the widow of the late Jean Saaren, former Palatinate tax collector from Grunau?, Maria Magdalena, in the local parish church.

- The surname name of Anna Margaretha married to Michael Kirsch, the Baker, remains unknown. She died in 1738, and he remarried to Anna Margaretha Wohlfahrt in 1739 (see below).

- Elias’s mother cannot be Anna Margaretha Wohlfahrt who married Johann Michael, the Baker, in 1739, after his first wife, Anna Margaretha surname unknown, died in 1738. Elias’s mother also cannot be Maria Margaretha Michet who married Johann Michael, the Mayor, in 1739 after his wife died in 1738 as well. Those two Michael’s must have felt like they were living parallel lives in many cases.

- There is no conclusive naming pattern.

- The godparents suggest that Elias Nicolaus might be the child of the Mayor, especially since the child born to the “other Johann Michael Kirsch” four months earlier has as a godparent the son of the brother of Michael, the Baker.

Nothing definitive yet.

Where else can I look?

Is there more to be learned in the 1753 accounting that Walter mentions? This one’s tough, because not only do I not have this document, I have absolutely no idea where to find it. I’ll use Walter’s notes since he states who is mentioned and clearly had access.

1753 Accounting

I suspect this accounting has to do with the Hallbergs and Fussgoenheim land inherited from Jerg, based on who is and is not mentioned.

Which Kirschs were in the 1753 accounting, and how are they related?

| Name in Accounting | Kirsch Parents/Husband | Walter’s Comments | My Comments |

| Anna Margaretha Spanier – alive in 1753 | Widow of Johann Michael who died in 1743 | Anna Margaretha Spanier (als Witwe in Rechnungslegung 1753 erwähnt) – Anna Margaretha Spanier (mentioned as a widow in accounting 1753) |

Johann Michael who died was the son of Jerg Kirsch and Margaretha Koch |

| Johann Michael Kirsch who died in 1743 | Jerg Kirsch and Margaretha Koch | Wife Anna Margaretha Spanier in 1753 is mentioned as Johann Martin Kirsch’s widow in accounting | |

| Johann Martin Kirsch (died before 1723) | Son of Johann Jacob Kirsch, son of Jerg Kirsch and Margaretha Koch | Wife Anna Elisabetha Börstler (als Witwe in Rechnungslegung 1753) ~ um 1727: translation: Anna Elisabetha Börstler (as widow in accounting 1753) ~ about 1727

|

Johann Jacob is the son of Jerg |

| Johann Michael Kirsch Sr. (died 1757-1759) (Mayor) | Johann Adam Kirsch died 1740 & Maria Koob. Johann Adam is the son of Jerg Kirsch and Margaretha Koch | in Rechnungslegung 1753 erfasst; v. Halberg 1757 durch Kassasionsdekret als Schultheiß abgesetzt; um 1744 mit seinem Vetter Michael (Bäcker) ausgewiesen, hatte 1753, 2 Söhne u. 4 Töchter in Ellerstadt, Deepl Translation: recorded in 1753; v. Halberg dismissed as mayor in 1757 by decree of cassation; around 1744 shown with his cousin Michael (baker), had 2 sons and 4 daughters in Ellerstadt in 1753

|

There are obviously some records in Ellerstadt in 1753 |

| Johann Peter Kirsch who died in 1760 | Johann Adam Kirsch and Anna Maria Koob, Johann Adam Kirsch is the son of Jerg Kirsch and Margaretha Koch | In 1753 accounting | |

| Johann Georg Kirsch | Johann Michael Kirsch died 1743 & Anna Margaretha Spanier | In 1753 accounting | |

| Johann Michael Kirsch, (the Baker) | Johann Michael Kirsch died 1743 and Anna Margaretha Spanier | In 1753 accounting | |

| Johann Nicholas Kirsch | Johann Michael Kirsch died 1743 and Anna Margaetha Spanier | In 1753 accounting | |

| Johann Adam Kirsch born 1731 died 1777 | Either Johann Nicholas (son of Johann Daniel) or Johann Jacob (son of Johann Michael died 1743, or Johann Adam) | In 1753 accounting |

I’d like to see where these people fit in a common pedigree chart, and I do a lot better with a visual.

I’ve color-coded people found on the 1743 map, in the 1753 accounting, individuals who are known to be dead, and those believed to be alive.

Elias Nicolaus Kirsch was not mentioned by name, so one would have to assume that is because his father is still alive. That pretty much puts the nail in the coffin, permanently, of Michael who died in 1743 being Elias’s father. But it does nothing to differentiate between the other two men, the Mayor and the Baker.

End of My Rope

I was officially at the end of my rope. I had learned a lot, but I still didn’t have a definitive answer. Furthermore, I didn’t know where to search.

I was not entirely convinced that Elias Nicolaus was the son of Michael Kirsch the Mayor, but Walter who had access to local, original records has him assigned as such. Furthermore, IF indeed the Johann Nicholas Kirsch baptized in January 1733 was the son of Michael Kirsch, the Baker, then my Elias Nicolaus, born four months later, HAS to be the son of Michael Kirsch, the Mayor, and Anna Margaretha.

I hate those “if” words, because so far, every piece of evidence has an associated “if.”

I organized and typed up the information we have and sent it off to Tom and Christoph for review. My head was spinning. So much data and so little hard and fast information.

Tom and Christoph both began looking at baptism records in Ellerstadt, and at records in Dürkheim which came up dry.

From Chris:

– I found a baptism of an Elias Hohl on 25 March 1751 in Ellerstadt, where the young Elias Kirsch, son of Michael Kirsch, was the godfather. Unfortunately, no further clue about which Michael his father was.

This is indeed my Elias, but no further identification.

– On 17 January 1753 in Ellerstadt, one of the Michael Kirschs was a godfather for a Michael Kirsch, son of Jacob Kirsch.

– On 4 Feb 1753 a baptism of Johann Jacob, son of Conrad Schumacher. Godfather was the stepfather Johann Jacob Kirsch from Fussgoenheim. (A Johann Jacob Kirsch, stepson of mayor Kirsch, is again godfather on 21 August 1754 in Ellerstadt. Is he the same Johann Jacob?)

Stepson and stepfather may not mean the same thing it means in today. Regardless, no further information about Elias.

– 4 March 1753 in Ellerstadt: baptism of Johann Nicolaus Moeser. Godmother was Catharina, daughter of mayor Kirsch.

Great information, but no cigar.

BINGO!

After running out of Kirsch records, Tom checked more records in Ellerstadt, where we knew they had lived, and some family members remained. As Christoph did, Tom searched for children baptized with the first name Elias or Nicolaus, given that children were named after the name of their godparent.

And there it was, tucked away in the godparent notes – a field almost never indexed, but where the nugget of gold we desperately needed was waiting:

Baptism: No. 11

Parents: Christoph Gutteberger, citizen here & wife, Anna Margaretha

A son, born and baptized and named Elias

Godparents: the unmarried Elias Kirsch, the legitimate son of the former praiseworthy mayor, Michael Kirsch; and the unmarried Maria Catharina Koob(in).

Born the 16th of October 1759

Baptized the 19th of the same

Tom, always understated simply said:

Important as it designated the father of our Elias Kirsch, the praiseworthy mayor, Johann Michael Kirsch and is the only Elias born in the correct time period.

Not only that, but this record is a twofer because we know that “former” typically indicates that Johann Michael Kirsch, Elias’s father, is deceased. The word praiseworthy makes me feel good, because that one word, not found in any other baptisms that I’ve ever seen, speaks volumes about how Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor, was perceived by the townspeople. Clearly, he was revered, at least by the good reverend who penned this record, probably for his lifelong battle and personal sacrifice, stepping forward and absorbing the brunt of Hallberg’s wrath for almost three decades.

Praiseworthy.

That alone is an honoring and fitting legacy for our Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor, who spent his life on this earth fighting the righteous battle against a powerful, wealthy foe. Kind of a David versus Goliath situation.

Praiseworthy, indeed.

Life Summary of Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor

Now that we know that Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor, is the father of Elias Nicolaus, let’s do a quick summary to order the facts of his life:

- Born about 1700 to Johann Adam Kirsch and Anna Maria Koob in Fussgoenheim.

- Married probably in 1724 or 1725 to Anna Margaretha whose surname has remained stubbornly unknown.

- Son, Johann Jacob, born about 1725, confirmed in 1739, died in 1760, married Anna Catharina Elisabetha Klamm.

- Daughter, Anna Barbara, born in 1726, married Abraham Zeitler, died in 1805 in Dannstadt.

- 1726 – New Lutheran church records begin. This could be when the current church was built, or it could have been as late as 1733/34 when Hallberg complained that the residents weren’t paying for the church construction.

- Daughter, Maria Barbara, born in 1727, nothing more.

- 1728 – Hallberg inherited half of Fussgoenheim and claimed common sheep pasture.

- 1729 – Hallberg began a resurvey of Fussgoenheim to divide land differently, cheating townspeople by shortening survey rod and claiming lands were abandoned that were not.

- 1730 – Hallberg obtained the other half of Fussgoenheim.

- Daughter, Maria Veronica, born in 1731.

- 1733 – Sheep pasture suit ends in compromise, with Hallberg obtaining pasture, but residents allowed to use it so long as not many sheep grazed.

- Son, Elias Nicolaus, born in 1733, died in 1804, married Susanna Elisabetha Koob, my ancestor.

- In 1733 and 1734, the War of Polish Succession was fought from 1733-1735, with portions fought in the Palatinate. In 1734, a camp for soldiers existed not far from Fussgoenheim.

- 1734 – Johann Michael’s mother, Anna Maria Koob died.

- Daughter, Anna Catharina, born in 1735, witnessed baptism in Ellerstadt in 1753, single.

- Daughter, Anna Margaretha, born in February 1738, died in September 1739.

- Death of Anna Margaretha, his wife, on December 10, 1738.

- We don’t know when Michael first became Mayor, but his wife’s death in 1738 identifies her as the wife of Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor. It appears that he remained mayor until 1757, throughout his exile, and into his return. That must have gauled Hallberg immensely. At least, I hope so:)

- 1739 – Married Maria Magdalena Michet, widow of the Palatinate tax collector Jean Saar, from Grunau on June 23, 1739. It’s likely that Maria Magdalena had children from her first marriage, so Johann Michael probably became a step-father to a number of children. Based on the fact that their last child was born in 1742, Maria Magdalena was probably about the same age as Johann Michael Kirsch, so she had likely welcomed 7 or 8 babies into the world.

- 1740 – Johann Michael’s father, Johann Adam Kirsch died something before 1740.

- Daughter, Maria Catharina, born 1741, probably died shortly thereafter.

- Son, Johann Theobald, born 1742.

- 1743 – Johann Michael refused to sign the Hallberg survey. He is listed as mayor, owning three properties and possibly more if I could read the entire list of names.

- 1743/1744 – Grendardiers stationed in Fussgoenheim, residents property confiscated.

- 1744 – Jailed for 14 days, then expelled to Ellerstadt.

- 1745 – Residents filed suit to obtain the return of confiscated items, which they won, but Hallberg raised taxes in retribution.

- 1746 – Additional suits filed, but the court did absolutely nothing with them. Twenty-four years later, long after Johann Michael’s death, the residents were still inquiriting about the suite.

- 1750 – Court rules that Hallberg had to allow expelled families to return and return their land to them, but he ignored the edict.

- 1752 – Holy Roman Emperor accused townspeople of not paying taxes and encouraged Hallberg to bring justice to Mayor Kirsch and the other townspeople. Hallberg threatened them with the military.

- 1753 – Court repeated decision and Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor, returned from Ellerstadt.

- 1753 – Accounting in Fussgoenheim includes Johann Michael Kirsch, the Mayor.

- 1757 – Removed as Mayor by order of the highest court at the request of Hallberg. The order included forcing villagers to pay all unpaid taxes, frontage money fees for tobacco scales, and threatened military intervention if they violated any part of the order. Hallberg wrote that he was very pleased, and no leniency should be shown to Mayor Kirsch.

- In October 1759, Johann Michael’s son, Elias, served as a godparent in Ellerstadt, where the records refer to him as the son of the “former praiseworthy mayor, Johann Michael Kirsch,” indicating that Johann Michael Kirsch had gone on to receive his just rewards.

This – THIS – is what leadership looks like.

Rest in Peace, Johann Michael Kirsch, you certainly deserve at least that.

_____________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- FamilyTreeDNA – Y, mitochondrial and autosomal DNA testing

- MyHeritage DNA – ancestry autosomal DNA only, not health

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload – transfer your results from other vendors free

- AncestryDNA – autosomal DNA only

- 23andMe Ancestry – autosomal DNA only, no Health

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Products and Services

- MyHeritage FREE Tree Builder – genealogy software for your computer

- MyHeritage Subscription with Free Trial

- Legacy Family Tree Webinars – genealogy and DNA classes, subscription based, some free

- Legacy Family Tree Software – genealogy software for your computer

- Charting Companion – Charts and Reports to use with your genealogy software or FamilySearch

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists – professional genealogy research

Discover more from DNAeXplained - Genetic Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

What a wild ride! Thank you for sharing it.

You wrote “so what are the chances that we would encounter this level of same-name confusion?” I thought 1% or less. Wonderful sleuthing work! I’m just not sure that former means deceased in this case. If the word mayor didn’t come right after it I would have agreed, but it could mean “former mayor” – especially since we know he was living two years prior in 1757. If Elias’ father was still living and not employed in another occupation he would be identified by “former mayor” as his occupation like all the other people in the records. Most records I see say deceased and that word is missing. I would have expected to see “deceased former praiseworthy mayor, Johann Michael Kirsch” or “former praiseworthy mayor, Johann Michael Kirsch, deceased.”

Outstanding work by all concerned.

I am encouraged to have another go at similar tangles in 1700s Cornwall, despite less evidence and local habitation for probably another 500 years.

The custom of naming a child after a god-parent was by then a long-gone medieval one for England, and in the early 1800s fewer people could read and write, so often at least one of the baptismal witnesses was often either a church warden or someone else who was literate. But during the 1700s many of my ancestor’s baptismal witnesses were family – in some way – so I look out for records that contain that information. (I don’t have godparent info for that time to check correlation with baptismal witnesses. There would usually have been three godparents, while there are only two witnesses recorded; for one difference.)

I really need to hire a researcher to look at the Cornish archives now.

But I have managed much with some wills that are online;

and lots of DNA work – I seem to have both segments from those lines and keen researchers with trees back that far, so have been lucky with one or two tangles.

Just saying that if the documents are not available there *may* be another option.

Good luck to those who give something similar a try.

Pingback: Margretha Koch, (born 1625-1630), The Preacher’s Daughter – 52 Ancestors #315 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Excellent work! I stumbled upon your page while researching my Saar ancestry, and I’m glad to be able to add a bit of additional flavor to the story of Johann Michael’s second wife, Maria Magdalena Michet. Maria Magdalena was the daughter of Jean Michet, the Mayor of Alsheim-Gronau (today known as Rödersheim-Gronau)(b. 1689, Alsheim-Gronau; d. 28 Nov 1727, Alsheim-Gronau) and Eva Ramsauer (b. 23 May 1677, Hohensachsen; d. 25 May 1723, Alsheim-Gronau).

Maria Magdalena’s first husband, Johannes Saar, was the Palatinate tax collector and lessee of the Gronau Castle (https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burg_Gronau). The children from Maria Magdalena’s first marriage were:

– Christoph Saar (b. 8 Feb 1722, Alsheim-Gronau; d. 7 Jun 1764, Ellerstadt). He married Maria Elizabeth Becher on 2 Jun 1744.

– Johanna Louisa Saar (b. 1727, Alsheim-Gronau; d. 4 Feb 1729, Alsheim-Gronau)

– Conrad Saar (b. 3 Jun 1735, Alsheim-Gronau; d. 30 Oct 1738, Alsheim-Gronau)

(see https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61157/images/46155_b289772-00015).

Oh, how exciting. Thank you ever so much for this information. Do you descent from Maria Magdalena?

I descend from Maria Magdalena’s sister, Maria Margarita Michet. So Maria Magdalena is my 7th great aunt, and her parents, Jean Michael Michet and Eva Ramsauer are my 8th great-grandparents!