Elias Kirsch and his family lived in Fussgoenheim – that much we know for sure. Unfortunately, the Fussgoenheim records are in sorry shape.

Fussgoenheim records include the following:

- Baptisms: 1726-1798 and 1816-1839

- Marriages: 1727-1768 and 1816-1839

- Deaths: 1733-1775 and 1816-1839

Those books are not complete, with pages missing and significant water damage. In the words of Tom, my trusty cousin and retired German genealogist, “these are some of the worst German records content-wise I’ve ever perused,” followed by, “your gang is never easy.”

Isn’t that the truth!

Given the situation, we’ll just have to piece Elias’s life together as best we can from what records do exist.

Keep in mind that my collaborators, Chris and Tom, did not transcribe every single church record. They have looked at most of the Kirsch records, and Thomas graciously completed a spreadsheet of what he found.

However, if the records are ever entirely transcribed, we may find significant missing information in the baptisms and other notes in records not found under the Kirsch surname. Godparent notes sometimes describe the relationships between various people, including the godparents and the child being baptized, or the godparents and the child’s parents, or even the godparents’ relationship to each other – any of which might serve as either outright confirmation or breadcrumbs.

So, hopefully, over time, we will discover more than we know today. We’ve been able to piece quite an interesting story together from the breadcrumbs we do have.

Elias Kirsch was Born in 1733

Elias Kirsch May 6 1733 baptism Taufen 1726-1798

“6ten May Ist Joh. Michael Kirsch und seiner Haußfrau Anna Margaretha Ein Söhnlein getauft worden noie [abbreviation for Latin “nomine”] Elias Nicolaus … gett [? cannot read this, but it must mean: witnesses] waren Elias Nicolaus Schnell und seine Haußfrau von Dürckheim”

Translation:

“On 6 May was baptized a son of Johann Michael Kirsch and his wife Anna Margaretha by the name of Elias Nicolaus. Witnesses have been Elias Nicolaus Schnell and his wife from Dürckheim.”

From this record, we know that Elias Nicholas was named after Elias Nicholaus Schnell who lived in Durckheim, now Bad Dürkheim.

It’s likely, but not a given, that Elias Nicolaus Schnell or his wife are related to either Johann Michael Kirsch or his wife, Anna Margaretha, whose last name we don’t know. Otherwise, there’s no reason for them to know each other or travel from Dürkheim to Fussgoenheim for a baptism. I was not able to find any records for Elias Nicholaus Schnell, unfortunately.

On the map above, we see that Bad Dürkheim is about 11 km or 6.7 miles from Fussgoenheim. Other locations relevant to this family are Ellerstadt and Mutterstadt where the Kirsch and Koehler families would both live when they migrated to America in the mid-1800s. Mutterstadt is about 5 miles via road from Fussgoenheim. In essence, this is all one big community.

All of these villages are located in the Rhine Valley plain, but Bad Dürkheim borders the beginning of the low-mountain region known as the Palatinate Forest, shown in green at left on the map above and in the photo below.

By Dr. Manfred Holz (Diskussion) – Self-photographed, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28600004

Elias Marries

We don’t know exactly when Elias married, but it was sometime before his first child was born in 1763. The available marriage records list dates from 1727-1768, but clearly Elias’s marriage record is missing. What we do know, though, through the subsequent baptism records of his children, is that Elias married Susanna Elisabetha Koob.

Children of Elias Kirsch

Tom found the baptism records for four children of Elias Kirsch and Susanna Elisabeth Koob born in 1763, 1766, 1772 and 1774.

The records go strangely mute after that.

Are there any other clues?

Multiple Men Named Andreas

Andreas seems to be a popular name in the Kirsch family.

Chris says:

For your information: There are burial entries for an Andreas Kirsch in 1762 (“Andreas Kirsch, the Elder”) and 1774 as well. So there have been several Andreas Kirschs in Fußgönheim at the same time.

This is potentially relevant because Elias named a son Andreas Kirsch in 1774.

There is a gap in the burial entries from January 1743 to 1762. (The burial in January 1743 for Johann Michael Kirsch the elder is the last one for a long time!). There is another gap from 1776 up to 1816. I found no burial entry for Elias Kirsch or his wife in the years from 1762-1775.

In summary, I am afraid there is not much more I can search for.

So, the entire family disappeared from the records? However, given the evidence that I’m alive and descended from Andreas, they clearly didn’t disappear in fact. It’s just that I can’t find them.

Did Elias Die in 1804?

I frustrate myself incredibly when it comes to the Kirsch family, in part because I began this research 40+ years ago which I simply wrote down what people told me and gave no though to recording sources, or asking them how they knew a given piece of information. It seemed rude to ask, like I was questioning their truthfulness when they were trying to do me a favor. Besides, it never occurred to me that I wouldn’t remember.

I was very young and very naïve. I know, right?!!

And I’m paying the price now. At least I was bright enough to WRITE THINGS DOWN!

In my genealogy software, I showed a death date for Elias Kirsch of May 2, 1804. A date that specific is too detailed not to have been found someplace. It’s not an approximation based on a child’s birth or marriage record, for example. But where did I come up with that date, and how?

I began searching relentlessly. Finally, I found a note from a German cousin decades ago where Elias’ death date was shown and the location was noted as Fussgoenheim, the village where Elias and my cousin both lived. This led me, of course, to presume (cousin word to assume) that the cousin had access to local records.

I had no idea at that point in time that the local Fussgoenheim records had been destroyed or were otherwise absent. Besides, absent at the local Family History Center might only have meant that the records weren’t (yet) filmed, not that they didn’t exist. I had already copied the Fussgoenheim church record images. I later copied the Fussgoenheim Civil Records as well, trying to fill in blanks, but all for naught.

Where did this death date come from? Not the church records and not the Civil Records. Not a family Bible because there wasn’t one. Believe me, I asked about a Bible AND I would have remembered that for sure.

Found It!

I had searched (again) some time ago when I started this article, but I searched one more time – this time with different search criteria. That old adage, “cast the net wider,” might work. I searched for any Kirsch who died in 1804 in Germany, with no first name or location.

What popped up was a shock.

A death record alright, but a FRENCH death record.

That’s not possible. Elias was very clearly German. Besides, he lived and died in Fussgoenheim, not Ludwigshafen, right?

These Ludwigshafen records show a death date of February 4, 1804 in Ruchheim for Elias Kirsch, but is this the same Elias Kirsch? The cousin’s original note said May 2nd, 1804 in Fussgoenheim.

Ruchheim is approximately 2.2 miles from Fussgoenheim, so it’s certainly possible. As we know, there were several Kirsch men in this area, so I was very cautious.

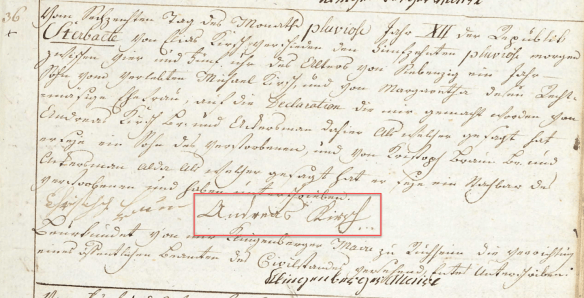

Tom originally translated the death record thus:

Elias KIRSCH

Date of the Act: 16 Pluviose in 12th year of the French Republic or 6 February 1804.

Death Act No. 36

The 16th day of the month of Pluviose in the year 12 of the Republic, the Death Act of Elias KIRSCH…..the 15th Pluviose in the morning between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m. at the age of 71 years son of the late Michael KIRSCH and Margaretha his rightful? wife from the declaration made by Andreas KIRSCH, ? and farmer here……and Kristoph Braun…farmer …..

Klingenburger, mayor and civil registrar. Mayor’s signature as well as signatures of Christoph Braun and Andreas Kirsch.

We asked Chris, a native German speaker to help fill in some of the blanks, and he very kindly did so, in the midst a whirlwind time in his life. (Thanks so much Chris!)

Death Act No. 36

The 16th day of the month of Pluviose in the year 12 of the Republic, the Death Act of Elias KIRSCH died [verschieden] the 15th Pluviose in the morning between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m. at the age of 71 years, son of the late Michael KIRSCH and Margaretha his rightful [yes! recht=mäßige] wife from the declaration made by Andreas KIRSCH, citizen [Br. = short for: Bürger] and farmer here, who declared that he had been a son of the deceased [als welcher gesagt hat er seie ein Sohn des Verstorbenen] and Kristoph Braun, citizen and farmer here, who declared that he had been a neighbour of the deceased and who signed this document. [Br. und Ackersmann allda [?] als welcher gesagt hat er seie ein Nachbar des Verstorbenen, und haben unterschrieben.]

Klingenburger, mayor and civil registrar. Mayor’s signature as well as signatures of Christoph Braun and Andreas Kirsch.

The parents’ names match Elias’s church birth record and the birth year too. Not only that, but Andreas is confirmed in this death record as the son of Elias. Everything aligns – same family. The discrepancy in the death month and year, in part, might be explained by a difference in date conventions in the US and in Europe. In the US, the abbreviation 2-4-1804 would be February 4, 1804 and in Germany, it would be April 2, 1804.

This sure make me wonder how many of my ancestors’ dates are incorrectly interpreted by me.

The death record is signed by Andreas Kirsch, and Andreas was Elias’s youngest child and one of three sons.

It looks like we found Elias’s death record alright, but how did Elias suddenly become French?

French Occupation!

The answer lies in the French occupation of the German left bank, the area between the Rhine River and France.

In the 1700s, Germany was still ruled by the Holy Roman Empire and was divided into sections ruled by Princes and royal families. The map below shows the Holy Roman Empire in 1789.

Wikimedia commons map by Robert Alfers

You can see the Pfalz region in the closeup, below.

The Rhine had for centuries been the road into the heartland of Germanic Europe facilitating transportation and trade. Of course, along that road marched and floated armies and invaders as well.

Wars in this part of Europe had been occurring regularly for hundreds of years by this time, and probably as long as humanity occupied this part of the earth.

The German people were weary. They had been displaced over and over again since before the 30 Years War which laid waste to and depopulated this part of Germany.

By the late 1700s, the German princes feared a Revolution, while the intellectuals hoped that the French would defeat royal absolutism. The common people, my families, were caught in the middle and could only deal with the outcome – whatever that happened to be.

When the French Revolution began in 1789, it was just one more in a succession of conflicts that dragged on until France officially occupied the German lands west of the Rhine.

In 1792, a conflict broke out, initially over the rights of German Princes with holdings in France, but it quickly expanded. The hostilities revealed that the civic ideals and French military were more than a match for the Germanic princes, vestiges of the Holy Roman Empire with no coordination among their fiefdoms, concerned about their own turf and not any consolidated whole.

The German lands saw armies marching back and forth, bringing devastation (albeit on a far lower scale than the Thirty Years’ War, almost two centuries before), but also ushering in new ideas of liberty and civil rights for the people.

Europe was racked by two decades of war revolving around France’s efforts to spread its revolutionary ideals, as well as to annex Belgium and the Rhine’s Left Bank to France and establish puppet regimes in the Netherlands, Germany and Italy. The French revolutionaries’ open and strident republicanism led to the conclusion of a defensive alliance between Austria and Prussia on February 7, 1792. The alliance also declared that any violation of the borders of the Empire by France would be a cause for war.

Prussia and Austria ended their failed wars with France but (with Russia) partitioned Poland among themselves in 1793 and 1795. The French took control of the Rhineland, imposed French-style reforms, abolished feudalism, established constitutions, promoted freedom of religion, emancipated Jews, opened the bureaucracy to ordinary citizens of talent, and forced the nobility to share power with the rising middle class.

Feudalism was a social system wherein the nobility held land from the crown in exchange for military service. Vassals were in turn tenants of the nobles and peasants, villeins or serfs were obligated to live on their lord’s land and give him homage, labor and a share of the produce in exchange for military protection.

In other words, no one other than the crown or nobility actually owned land. Freedom was restricted and military duty was mandatory. It wasn’t quite slavery, but it certainly restricted freedoms in many ways. In essence, it was economic slavery with no way to free oneself. Even emigration required permission.

The French-imposed reforms beginning in 1793 proved largely permanent and modernized the western parts of Germany. However, despite these welcome reforms, when the French tried to impose the French language, German opposition grew in intensity. The French had crossed an emotional line in the sand.

A Second Coalition of Britain, Russia, and Austria then attacked France but failed. Napoleon established direct or indirect control over most of western Europe, including the German states.

Clearly, based upon these civil records, the mandate of the French language was implemented and upheld, at least officially. Knowing the tenacious nature of the German people, I’m sure not one word of French was spoken when they had any choice.

The Encyclopedia Britannica adds:

After 1793 French revolutionary troops occupied the German lands on the left bank of the Rhine known as the Palatine Region, and for the next 20 years their inhabitants were governed from Paris. Yet there is no evidence that the Germans were dissatisfied with French rule or at least no evidence that they strongly opposed it. Devoid of a sense of national identity and accustomed to submission to authority, they accepted their new status with the same equanimity with which they had regarded a succession to the throne or a change in the dynasty.

Wikipedia tell us that:

Following the Peace of Basel in 1795 with Prussia, the west bank of the Rhine was ceded to France.

Napoleon I of France relaunched the war against the Empire. In 1803 he abolished almost all the ecclesiastical and the smaller secular states and most of the imperial free cities. New medium-sized states were established in south-western Germany.

The Holy Roman Empire was formally dissolved on 6 August 1806 when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) resigned.

In 1806, the Confederation of the Rhine was established under Napoleon’s protection.

By ziegelbrenner – own drawing/Source of Information: Putzger – Historischer Weltatlas, 89. Auflage, 1965; Westermanns Großer Atlas zur Weltgeschichte, 1969; Haacks geographischer Atlas. VEB Hermann Haack Geographisch-Kartographische Anstalt, Gotha/Leipzig, 1. Auflage, 1979., CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9024294

The Confederation of the Rhine, a confederation of client states of the First French Empire, existed from 1806 to 1813.

With the defeat of Napoleon’s France in 1814, Bavaria was compensated for some of its losses, and received new territories such as the Grand Duchy of Würzburg, the Archbishopric of Mainz (Aschaffenburg) and parts of the Grand Duchy of Hesse. Finally in 1816, the Rhenish Palatinate was taken from France in exchange for most of Salzburg which was then ceded to Austria in the Treaty of Munich (1816).

It’s no coincidence that we see the church records recording births, deaths, and marriages resume, in German, in Fussgoenheim in 1816.

The French rule was over. The official language returned to German, although I’m willing to bet that while the upper-class society spoke French, the peasants and farmers in the villages never did.

They simply waited.

Some, of course, like Elias, died waiting – but his grandson Philip Jacob Kirsch, born in 1806, two years after Elias’ death, tired of constant turmoil in the Palatinate, would take his German-speaking family to Indiana in 1848 where they still spoke primarily or at least occasional German for another 100+ years.

Some of that strong German bloodline is discernible in his descendants today.

Kirsch Autosomal DNA

Because the Kirsch family didn’t immigrate until the mid-1800s, we don’t have as many descendants in the US today to DNA test as lines that have been in the states since colonial times.

Thankfully, another Kirsch descendant and his family are also interested in the Kirsch genealogy and agreed to DNA test.

It’s particularly interesting, because while Mr. Kirsch’s daughter and I don’t have an autosomal DNA match, he and my mother have a significant match, on six substantial segments, shown in red below. In fact, other than immediate family, my Mom is his closest match.

On the chromosomes above, Mr. Kirsch is the background person with mother being the red segments matching Mr. Kirsch. For purposes of comparison, I’m the light blue that matches with Mr. Kirsch and my mother on chromosomes 8 and 11. Notice the huge red piece of DNA that I didn’t receive from Mom on chromosomes 3 and 14, the first half of chromosome 11 and the smaller segment on chromosome 4. In these locations, I received my mother’s father’s DNA, because I certainly didn’t receive her DNA from her mother’s Kirsch lineage.

The largest segment that Mr Kirsch and mother share is 42.67 cM and the smallest segment larger than 5 cM is 10.27 cM. Four other people also match both Mr. Kirsch and mother, above, as well. Two matches don’t have trees, one lives in Germany and one in the Netherlands.

Of course, Mom and Mr. Kirsch share both the Kirsch and Drechsel DNA, given that Elias’s great-grandson, Jacob Kirsch, married Barbara Drechsel in Aurora, Indiana. We could be seeing a combination of segments descended from both Barbara and Jacob.

I inherited very little of this specific Kirsch/Drechsel DNA, and my children inherited even less. Obviously, Mr. Kirsch’s daughter didn’t inherit the segments from her father that I share with him, given that she and I don’t match. It’s amazing just how quickly descendants can go from 163 cM of shared DNA in one generation between two people on 6 segments greater than 10 cM, to no match between their children. Genetic roll of the dice.

I do wonder if any of these segments descended from Elias or if they were introduced by a wife’s line in the 4 generations (inclusive) between Elias Kirsch/Susanna Elisabetha Koob and Jacob Kirsch/Barbara Drechsel where the line splits into sibling lines in the late 1800s.

Of course, every segment has its own unique history, so these segments could descend from multiple ancestors in the pedigree chart, above – Kirsch, Koob, Koehler, Lemmert and/or Drechsel.

We won’t know unless some Kirsch and Drechsel descendants who descend from ancestors upstream of Jacob and Barbara test and match some of these segments. One thing is for sure, one way or another, this DNA originated with our ancestors someplace in modern day Germany, a place then known as the Holy Roman Empire.

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some (but not all) of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- Family Tree DNA

- MyHeritage DNA only

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload

- AncestryDNA

- 23andMe Ancestry

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists for genealogy research

Cool! I love the historical context. So much drama!

Today, the French aren’t fans of Napoleon either. He was a dictator, and many Frenchmen died fighting his wars.

Roberta: I love your posts! On the note in the first record: “[cannot read this, but it must mean: witnesses]”, absolutely right using the context. I can confirm that it says Gev: the colon in Germanic script indicates it is an abbreviation, and the letter that looks like a double “tt” is a “v” with an artistic sweep. So Gev: is short for Gevattern, baptismal sponsors. I also appreciate your DNA inclusion — it is rather amazing how much some can “drop out” in just one generation. A good lesson about testing more relatives…

I was really surprised to see how much Mom shared with him given that his daughter and I share none.

Your history is saving me hours of research for which I cannot thank you enough. Those maps are fantastic! I suspect you know that Kirsch means Cherry in English. Any idea how they got that name? Were they originally orchard owners growing cherries?

I’ve wondered.

Pingback: The Saga of the Three Johann Michael Kirschs – 52 Ancestors #288 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

I read your report with great interest. My great uncle told me that our family was originally called “Kirsch” and that the “-ke” was added when the family emigrated from the Alpine region through Silesia to the province of Poznan, now Greater Poland. At the end of the 19th century Franziska, Otto and Alexander (*1858) Kirschke emigrated to Michigan City (IN). The architect Otto (*1850) later lived in Nebraska. Franziska (*1848) marries Otto Klopsch. All three had many descendants in the United States. Otto visited Germany in 1914 and did genealogical research. He found out that the grandfather of his grandfather Carl Ludwig K. (*1771) was called Christoph Kirsch(ke). All documents were lost in 1945. Greetings Ulrich Kirschke

Translated with http://www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)