My Grandfather, John Whitney Ferverda (1882-1962) worked for the railroad for several years. In fact, it was the railroad that was responsible for John meeting my grandmother, Edith Barbara Lore.

Born in 1882 and trained as a teacher, John Ferverda instead went to work for the Big Four railroad in 1904 as a station agent and telegraph operator in Silver Lake, Indiana, near where his family lived. By 1907, John had accepted a position in Rushville, Indiana as station agent where he would meet Edith who was destined to become his wife – and my grandmother.

A station agent, especially in smaller stations, was responsible for everything. People, cargo, schedules and especially telegraph communications known as telegraphy which kept everyone on time and safe.

On their marriage application on November 16, 1908, John lists his occupation as a telegraph operator.

In January 1910, Edith and John returned to Silver Lake where he became the station agent. They purchased the house next door to the depot.

John’s brother, Roscoe Ferverda bought the house across the street and he too eventually became the station agent after my grandfather resigned the position. In the 1930 census, Roscoe was the station agent at Silver Lake.

In 1913, based on newspaper articles, it appears that John was assigned to Markleville, just north of Rushville, perhaps only temporarily.

He was back in Silver Lake before 1915 when, according to the November 13th edition of the Fort Wayne, Indiana newspaper, another agent was sent as a relief agent for “John at the Big 4” while he had surgery on his eye in Cincinnati. Hmmm, I didn’t know my grandfather had surgery on his eyes. I wonder why. Photos in later years show a droopy eyelid. I also wonder if either the condition or the surgery had anything to do with what happened in January 1916.

John was apparently back at work by November 27th, when the newspaper announced that the stork had left a baby boy at the home of ” John Ferverda, our genial agent at the Big Four station” and his wife.

On January 8, 1916, the Rushville Republican newspaper carried an article stating that John Ferverda, “the Big Four Agent at Silver Lake,” had resigned his position with the railroad and had purchased a hardware store with a partner.

The History of Kosciusko County, Indiana, published in 1919, provides us with a little more information about John Ferverda.

Having mastered the art of telegraphy, he entered the service of the Big Four Railway as an operator, was assigned at different stations along that system and remained in that service about 10 years.

The Big 4 Railroad

I had never heard of The Big 4 before, and as it turns out, there are two Big 4s, also written as Big Four. The one that interests us is the railroad company that operated across Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Ohio.

This map shows the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway (Big Four) drawn on the New York Central system as of 1918.

In 1906, the Big 4 was acquired by the New York Central Railway which operated it independently until 1930. In 1968, the line was incorporated into Penn Central and later into Conrail, CSX and Norfolk Southern.

Telegraph Operator

How or why John Ferverda learned to operate a telegraph machine is lost to history. The local history book indicated that he lived at home until he was 22. John attended a teacher’s academy, was credentialed to teach, but never did. In 1904, he would have been 22 and finished with his classes.

Given that the article in the Kosciusko County History book states clearly that he had mastered the art of telegraphy, then entered the Big Four Railroad service as an operator, we know that he didn’t learn on the job. This causes me to wonder where he practiced, given that his parents were Brethren, lived in the country, and assuredly did not have electricity in their home.

One cannot learn Morse code, the “language” of the telegraph without practicing and becoming proficient. Proficiency using Morse code is measured by either words per minute or characters per minute, and a telegraph operator for a railroad had to be proficient and speedy, which means he had to have practiced regularly using a unit to both send and receive.

I’ve been curious for some time – what, exactly, did a telegraph operator for a railroad do? How did they communicate before the remote areas were entirely wired for electricity? According to my mother, their house didn’t have electricity initially, so the depot next door probably didn’t either. John worked at this profession for a dozen years, a significant amount of his life.

I wanted to know more. Genealogists always want to know more!

By the time I came along, telegraph operators were either obsolete, or at least I had never come across one. The Big Four was gone, and my grandfather died before I could ask him any questions at all.

My mother wasn’t born until 1922, several years after John had resigned the position, so she wouldn’t have been able to answer many questions either.

However, I do have a secret weapon resource at my disposal.

My husband, Jim.

No, Jim didn’t know my grandfather, but Jim is a super bright geeky “radio guy,” meaning an amateur radio operator, known colloquially as a “ham,” and has been for about 50 years. Literally since he was a kid. He was licensed by the FCC to operate a radio before he was old enough to drive! And, he’s proficient at Morse code. Sends, receives and understands it. Plus, he’s a history buff. My lucky day!

If you have a question about radio, or anything to do with radio or electronics, just ask Jim, because if he doesn’t know the answer, guaranteed, he’ll find it for you. And he’ll enjoy it to boot.

Jim and the ARRL

Jim (call sign K8JK) just happens to be the Michigan section manager for the ARRL, the American Radio Relay League, headquartered in Newington, CT.

Recently, Jim attended training at the ARRL headquarters and invited me along. While Newington, in and of itself, unless you’re a “ham” isn’t any sort of Mecca, I like to support his endeavors AND I’m a ham myself, just barely.

I am also extremely interested in genealogy and history, which I know comes as a shock to my readers, and when I discovered that I had ancestors that settled within an hour’s drive, I was all in. Oh yea!

Each day I dropped Jim off at ARRL headquarters, and at the end of the day, picked him up again.

On the last day, the class attendees really did get to go to “ham Mecca” and entered the sacred ground of the small house located in front of the current ARRL building. That initial house had been the location purchased by the founder of the ARRL, Hiram Percy Maxim, whose “rig” has been preserved with its original call sign of W1AW.

The building includes several operator booths, along with antique radios and telegraph keys. Each class attendee was able to spend time transmitting in the original W1AW “ham shack” as a guest operator.

Now you know where this is going, right?

Amateur radio operators still use Morse code at times to communicate, and telegraph keys were created and used for exactly that purpose – in train stations and depots. My grandfather clearly knew how to use this equipment and did daily for a dozen years. I’d still love to know why he decided to take up telegraphy, because aside from trains, I don’t know why or who else in northern Indiana would have a need for a telegraph operator. Perhaps he saw an opportunity and embraced it.

Thank goodness he did, or I wouldn’t be here. So you could say I’m in eternal debt to Morse code for my very existence.

Who knew?

Questions – So Many Questions

I really enjoyed visiting the museum in the W1AW building – and peppered Jim with questions.

What is that?

How does it work?

Which one of these keys, the device used by telegraph operators to transmit Morse code, would have been used by the railroads?

Between 1904 and 1916?

How about on the Big 4 Lines?

How did the keys work?

What is that lever?

How do these connectors work?

What’s this?

Why is there air?

Morse Code, Telegraphs and Why There’s Air

Jim very graciously agreed to explain all this, in technical terms, but not too technical. Just technical enough. I get the idea somehow that he made the offer in self-defense, because by that time, I was digging through his boxes of “sacred antique stuff” (also referred to as “junk”) hoping to find an old telegraph key that might have been used in a Big 4 depot.

I allowed myself to be shooed out of his office when he offered up the article:)

Jim’s guest article begins here:

Hi, my name is Jim Kvochick (K8JK), or Mr. Estes as I’m called at genealogy and DNA conferences. My lovely wife, who is also a ham operator (K8RJE), has asked me to explain what life was like for a telegraph operator when her grandfather, John Ferverda, was working for the Big 4 Railroad in Indiana between 1904 and 1916. It’s hard to believe that was a century ago. Morse code was invented in 1836 by Samuel Morse and is still used in various formats today. In many ways, Morse code as a language is universal and timeless.

Ever since the beginnings of time, people have been trying to communicate over distances greater than the human voice could reach. Early attempts included the use of smoke signals, signal fires, waving flags, and the moving arms of semaphores, shown below.

Mirrors were also used to flash the image of the sun to distant observers.

Railroads had a need for communications as well and clearly their requirement extended beyond the range of visual communications. Early attempts involved a method for attaching hand written messages called “train orders” on a large hook extending from the station. As the train slowly approached the train depot, the conductor on the moving train would reach out to grab the incoming messages, and “hook” the messages or mail destined for that location. If the conductor missed, the station operator had to run alongside the moving train with the messages on a long pole, reaching towards the conductor.

Train orders advised the locomotive engineer of changes in schedule, planned stops, or any other details needed to complete their run. Harnessing electricity was a welcome innovation but adapting that technology to long distances was challenging.

Utilizing electricity, wires were stretched from one point to another and an electric current was either allowed to flow through the wires or broken by a switch called a telegraph key. The key below dates from about 1900.

By Hp.Baumeler – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61723472

The electric current was first used to make marks on a paper tape and later, it was used activate a “sounder” which made clicking sounds. The short and long times between the clicks could be decoded into letters from the alphabet.

By Sanjay Acharya – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15733842

The round discs on the sounder key above are electromagnets and the sounder portion is the spring lever with the tab on the left, shown with the red arrow. The lever gets pulled up against the large metal bar to its right, between the sounder and the electromagnets and makes an audible click when the two pieces of metal touch.

By the early 1900’s most train stops utilized mechanical sounder devices and trained the station operators on sending and receiving Morse code.

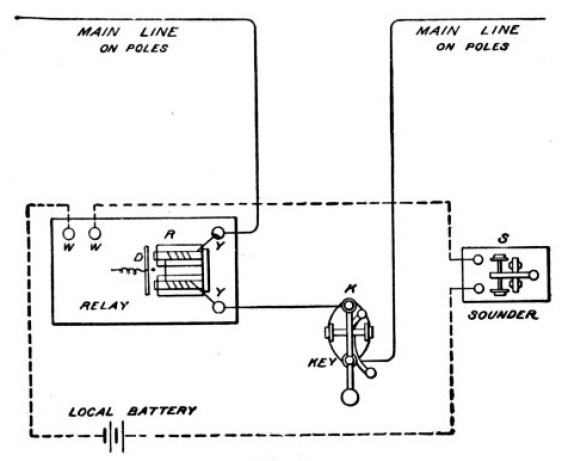

The schematic shown above is the design of a typical station telegraph, like what would have been on John’s desk.

This revolutionary discovery allowed people to communicate instantly over distances that had required days or weeks for horse or train-carried messages.

Telegraph stations were set up along railroads first because the right-of-way had already been cleared and it was easy to set up poles to carry the telegraph wires, although unexpected challenges arose. For example, while curved train tracks weren’t problematic, it took several failed attempts before learning that poles located on curves needed to be braced or they fell over due to the weight of the wires. Copper wires stretched, steel wires rusted and broke. Eventually, through trial and error, the right combination was achieved of braced poles and copper coated steel wire.

Railroad dispatchers sent messages via telegraph to control the movement of trains and the wires also began to carry messages telling of news events and business transactions.

Of course, this also meant that the telegraph operator knew everything within the community, and in particular, was the first to receive messages deemed important enough to be telegraphed to the recipient.

It has been said that the “electric telegraph” was the most significant invention of the 19th century. At the very end of the 19th century, it became possible to communicate by telegraph without using wires. This ‘wireless’ telegraph system paved the way for all of today’s complex wireless communications systems.

Although telephone communication began in the 1880’s within a local geography and expanded into long distances beginning in the 1890’s; telegraph signaling held the advantage due to lower costs and minimal infrastructure required. Radio communications was beginning to come into popular usage, but the cost per unit was too prohibitive to deploy widely. To further reduce the cost of installing the telegraph system, only a single wire was used, with reference to an earth ground to complete the circuit.

Many of the stops along the train tracks did not have electric power, so to successfully operate the telegraph stations at that time required the use of batteries.

Batteries in the 1900’s were large open jars containing electrodes and acid, requirimg constant attention by the station operator. Remember too that in many cases there was no commercial power available to charge these batteries. John Ferverda would most likely start out each day with a check of the battery condition and perform the required maintenance to keep his telegraph station running.

Early batteries used highly toxic chemicals which were stored in the station agent’s office. These batteries and their chemicals including sulfuric acid, zinc and copper, created toxic gasses which were eventually vented outside the agent’s office. Perhaps it’s a good thing that John Ferverda only worked as a station agent for a dozen years.

Early telegraph operators would have used the American Morse code, a predecessor to the more widely used International Morse code of today. While the American version relied heavily on the specific timing between the dots and dashes, the International version was far more forgiving, in trade for making some of the letters and numbers slightly longer.

There were numerous styles and variants of older telegraph keys and many are still being used by amateur radio operators today.

Most likely John Ferverda used a variant that looked similar to the model below from the ARRL collection.

The telegraph operator was still in demand and used for information at depots or stations well past the 1950’s. Although many train lines experimented with two-way voice radio during the 1930’s, a truly practical solution wasn’t installed in volume until the late 1960’s and early 1970’s.

Today, radio and satellite communication dominate tracking and routing our modern railways.

The humble telegraph paved the way for the wireless communications that all phone “operators” today utilize – those small electronic boxes that we carry in our pockets and love. John Ferverda was a very, very early adopter of the predecessors to cell phones of today.

Oh, and by the way, if anyone happens to run across the telegraph key from the station in Silver Lake or Rushville, Indiana, or any of the Big 4 depots in that region, perhaps at an auction or antique mall, please let me know because I’ve love to surprise my wife. (Shamelessly added to this article by said wife.)

Acknowledgements:

My thanks to the ARRL for their hospitality and to Jim Kvochick for explaining the history of telegraphy and why there’s air, or least why there’s Morse code.

And seriously, if you do run across a telegraph key from the early 1900s in Northern Indiana, I really do want one and would be forever grateful. I sure wish I had John Ferverda’s original equipment.

What’s the history of radio or railroads in your family?

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- Family Tree DNA

- MyHeritage DNA only

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload

- AncestryDNA

- 23andMe Ancestry

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists for genealogy research

Discover more from DNAeXplained - Genetic Genealogy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The man I knew as my Grandfather, I later discovered he was Grandmother’s second husband and not my Father’s Father, worked for the Chicago and Burlington (I think that’s it) RR. He worked Maintenance of Way in Beardstown, IL. My father was a Ham for many years and operated his station from our basement.

My grandfather ALSO studied to become a telegraph operator! Used to have a picture of him at a desk where he was working the machine in Middle Tennessee, but a computer crash years back destroyed the picture alas. Have asked cousins to check and see if they have a copy of it. If so, I will share with you, Roberta. Might be like the machine your grandfather used : )

I’d love that! Hope you find it.

Dear Roberta Estes,

Ham Radio has been a part of my Reynolds family for many years. My half-brother, Norman Reynolds, got his license in 1926 with the call sign 5ATZ. Later, he became W4LBW and W9GGE. Herbert Hoover was Secretary of Commerce when Norman got his license. In the old days, everyone built their own equipment. This Reynolds family probably had about 8 active operators over the years.

I loved your historic interesting post.

I wish I could find any evidence that my grandfather was a ham.

I wish you success in that department; that would be a great emotional boost.

My husband still builds a lot if radios and fixes them for others.

That’s wonderful! I certainly remember the vacuum tube days and the first time I saw a transistor radio. Families used to sit around the radio in the old days before TV and listen to radio broadcasts.

This is really wild, I looked up some of the old railroad maps not long ago in effort to get some folks to understand that travel in the 1800’s was not as hard to do in the Eastern United States (West of the Mississippi River) as some people believe. There were also River Boats, Canals, Wagon Trains and Stagecoaches.

That lead me into looking up some maps on Telegraph Lines and then is when I realized that Samuel Morse invented the “Morse Code”, my GGM straight up my maternal line was born a Moss, other spellings are Morse and Marsh. I tried but never connected my line to Samuel’s, but who knows?

I was going to leave some copies of the old maps I found but do not find a way to leave a picture.

You can leave links but the platform doesn’t support photos in comments.

Awesome, here a ham there a ham! Everywhere a ham.

I share a common grandmother with Samuel Morse.

Eleanor Helena Morse 1614 – 1694!

Great article!

Kg6dvd

Enjoyed your article Roberta. My grandfather’s story was very similar to yours. He was born in 1879 Lee county MS. I was told that he wanted to be a dentist and I believe he even attended a school for time to gain that knowledge. For whatever reason being a dentist did not happen and around 1900 he became a station agent at a small town in southern Mississippi (don’t remember the name of the town). Later he was the station agent for the Santa Fe RR in Oak Cliff Tx, Joshua, TX, and finally at Justin, Tx where he died in 1943 while my father was away in the Navy.

My father has told me storyies about some of the things my grandfather was responsible for. As you say, the station agent in a small town was responsible for everything that happened. He would make sure the water tank was always full. He would put the mail bag on a “hoop” and hang it out for the train to pick up as it went flying by, When there were passengers or cargo to pick up he would send instructions via the telegraph so the train would stop.

I think learning telegraphy was equivalent to being in IT today. It was a path to a good job. My father told me that his father told him; “Learn telegraphy and you will always be able to find a good job”.

Thank you for these details. You’re right though about always being able to find a job.

In the early 50s, I attended high school in the Oak Cliff part of Dallas, TX (W H Adamson). I don’t remember where the terminal was located, however.

This is so cool, Roberta and Jim! My dad was a ham in Illinois, getting his license in the 1920s W9AHC. I didn’t know ARRL headquarters are in CT! I did try to learn enough code from an old Army code machine we had when I was a kid. It had paper tape and a sounder of some sort. I didn’t practice enough to get very good at it. Thanks for the story. 73s. Jane

Sent from my iPhone

You don’t have to know Morse code to get your license today. 😁

Great Article!

My Grandfather was a Telegraphist in the Navy in WW2 so I read your article with great interest.

Alaina

My great-grandfather on my dad’s side worked for the railroad, in Oklahoma. He invested in land properties as he built the track lines. Legend is that he “had a nose for oil” . But not really, he didn’t, there was no oil on the many properties he found but it’s lots of fun to belong to my great-grandfather’s irrevocable family trust, it’s like a long-distance family social club. The railroad him started on his realestate career and my great-grandfather did well with his surface land sales (he always retained the useless oil and mineral rights) .

My uncle (from my mom’s side) is a long-time ham radio operator, and my cousin too. When I started my homestead, in New Mexico, they sent me the ARRL handbook. I’ve been studying to take the test, I bought a rig already, operator license and I’m good to go 🙂 .

My grandfather was a ham and I spent hours as a child watching him “talk” to people with code and voice. I tried but never became proficient at code. I did become a ham, after he died, and took his call sign – K6PON. Thanks to you and your husband for an interesting and informative article.

Donna

Thanks for the trip down memory lane via telegraph wires. I have a picture of a group of students standing in front of the Dallas Telegraph School in Dallas, Texas. Unfortunately it is undated and the letter of recommendation for my daddy who was a recent graduate is also undated. I suspect they are from the 1907-1910 time period.

Have you googled that institution to see what you could find? I didn’t know there were schools. How interesting.

Since I was born in Dallas, I would be interested in more information about the Telegraph School. I did found out that there was a Telegraph, Texas:

http://www.texasescapes.com/TexasHillCountryTowns/Telegraph-Texas.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telegraph%2C_Texas

Here is a link to the Dallas Telegraph College:

https://flashbackdallas.com/2014/02/12/start-your-brilliant-career-at-dallas-telegraph-college-1910s/

Also see: http://www.texasescapes.com/MikeCoxTexasTales/Wired.htm

https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/egt01

https://flashbackdallas.files.wordpress.com/2018/03/dallas-telegraph-college_1889-directory.jpg

It shows two street addresses with Frank Joy as the Manager…

One more photo here:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Dallas,_Texas#/media/File:Group_of_Students_from_Dallas_Telegraph_College_(27207029993).jpg

I’ll try again on the photo because the earlier posted link got truncated.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/24/Group_of_Students_from_Dallas_Telegraph_College_%2827207029993%29.jpg

The singer and movie cowboy Gene Autry started out as a railroad telegrapher (reportedly discovered by Will Rogers at an Oklahoma station). He grew up about 100 miles from Dallas. I wonder if he went to that school. There couldn’t have been many of them.

It could have been although the town of his birth wasn’t that close to downtown Dallas where the two colleges were located. His family moved to CA in the 20s. After leaving high school in 1925, Autry worked as a telegrapher for the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway per wikipedia. I do remember learning Wig-Wag in the Boy Scouts. My nephew and I studied morse code in the early 50s and we took our license test in the Dallas FCC office on the same day.

Lookslike your family has TWO fine writers!!

What’s the history of radio or railroads in your family?

Well, as long as you asked.

Radio: The Boy Scouts required you to learn Morse code to be promoted. I learned on a set of World War I “clickers” that our troop had acquired surplus from the Army for free. They were already 30 years old at that time. Two car-battery sized heavy wooden cases connected by a spool of single stand wire. Each box held a wet cell battery and a clicker telegraph key. The keys were very much like the ones your husband showed. They were used to communicate between the trenches during that war. An intrepid soldier would run between the trenches, unspooling the wire as he went. It wasn’t until very many years later when I got my Ham license to use on my sailboat that I finally learned the Di-Dah tones of an electric key.

While a youngster, I built from plans in the Boy Scout magazine, an unpowered broadcast band radio receiver using a razor blade and pencil lead as a simulated crystal, a coil from wrapping wire around a toilet paper tube, a paper clip tuner, and a hundred foot wire antnna stretched to a tree from my bedroom window. Very successful until the ungrounded antenna interfaced with a lightning storm. I was disadvantaged and didn’t own a cell phone.

Railroads: Not really much except for riding the electrified Long Island RR out past Smithtown where they still had to switch to one of the few remaining steam engines to make it the rest of the way to the Hamptons. Also, took a wonderful cross country and back RR sightseeing trip to the Scout Jamboree held at the vast deserted Irvine Ranch outside Los Angles, just before it was developed into the modern city. I remember passing through vast orange groves from LA to Anaheim. There was some rumor that the donation of use of the ranch land to the Scouts had some great tax advantage to the corporation. Several of the Long Island Boy Scout councils had chartered cars for that train. For most of the troops, the kids had to sit in coach cars for the long trip; ours, being better off, had the only Pullman car on the train. Stewards to make up our bunks, air conditioning, etc. Luxury.

Bob N3OZB

What great memories. I didn’t know that about scouts.

Rethinking the Irvine Ranch Company slur, that was unnecessary. No evidence at all. They were probably just goodhearted, letting us use temporarily unused property. That’s how rumors start.

My grandfather worked for the InterUrban in Huntington, IN and was a rail car inspector in IN, OH, and CA. Don’t know which railroad, though. I have a picture of him in front of a station, but not sure WHICH station as he is standing in front of the name.

Your post brought back memories. My husband 45 years ago became a hamm – BLP that is missing a number but I can’t remember …… do radio sets pull A LOT of electricity? He lived with a daughter for a while and she was very upset about her electric bill……

The other memory is as a kid we had a brown plastic Morse code machine that had been my dad’s in the navy – WWII version – it had a little light that when on and off as you taped out the letters.

Enjoyed all the other historic memories of others as well.

I hadn’t heard about a plastic Morse Code machine that was used for practice. It does make sense because the Morse Lamp was actually used in WWII. I used to see it in old war movies too.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signal_lamp

Re: hams using a lot of electricity; I suspect it wasn’t due so much the raw power consumed by the transmitter and receiver as it was the total power consumed in the Ham Shack with lighting, A/C, and soldering irons, etc.

Burton

Hello – greetings from Australia

Your article was very interesting. Although I am not a HAM, my father was from the age of 16 (in 1935), but never got a rig going, which was sad. I placed his call sign VK2ANV on his memorial plate when he died.

I have a passion for railways (ie railroads) and collecting old railway signalling equipment plus getting it working. I am an electrical engineer and one aspect of my railway interest is the history of the use of electromagnetism in railway signalling. Bearing in mind that batteries and electromagnets were invented in the mid 1800s, they got used for functions like the railways and telegraph very quickly.

It is also interesting how the telegraph spread along the railways in the US as they were the only people with the vacant real estate. However, most railways were hesitant to adopt the telegraph because they thought people would send messages rather than visiting adjoining towns to do business!

It is hard to imagine a time without electricity. One of the items in my research is from a town in north west New South Wales (the state where I live). This town was the first town in Australia to use electricity to light the streets. However, I have seen a letter noting that when the electric telegraph arrived in about 1860, it was the first use of electricity in the town.

I have recently obtained a wonderful collection of railway morse code equipment and I am wanting to get it working. So, I am doing as much research as I can. Included in the collection are some rolls of paper taper on which the morse messages have been imprinted by a morse inker. One roll has been wrapped up and says that it was removed from the machine at 2pm on 3 January 1986 – wow – imagine the history that is wrapped into this roll. I also have a number of telegrams from the same period that are some sent and some received. There is one transaction where someone is asking for a 7 foot coffin to be sent urgently on the 1pm train as the burial had to occur that day and then a reply follows shortly after confirming the arrangement!

I am interested in the circuits used and I wonder if I may contact your husband some technical questions which he may or may not be able to answer. My email address is rob_cse@yahoo.com

There was also a brilliant system developed by Western Electric just after WWI for calling stations. These were used in Australia between the train controllers calling the signal boxes along the lines. One of the short-comings of morse code is that there is no privacy and also all the operators had to listen to every message to see which ones were addressed to them. The Western Electric system used coded switches at the central office to send a string of pulses which would only ring a bell at the similarly coded out-station.

Thank you for recording your memories and research.

regards

Robert Bremner

I just sent my husband your info. I’m sure he will be in touch. Have fun!

Pingback: Evaline Louise Miller Ferverda’s Will, Estate and Legacy – 52 Ancestors #243 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy