William and James are both common names, as is Moore. Saying this family has been difficult to research is an understatement. I’ve made multiple trips back to Halifax County, Virginia over a period of 3 decades – each one unearthing new tidbits, but also adding more questions than answers.

Slowly, a painting of the life of William Moore has unfolded, in quite an unexpected way. But first, I had to figure out which William Moore was mine.

Multiple William Moores

There were at least five, count ‘em, five, William Moores in Halifax County, Virginia in the late 1700s, and at least two James Moores. Of course, every William and James had children named William and James, and Thomas too. Oh yea, there were Thomas Moores in Halifax connected to the Williams and James. By 1800, we had another 3 “disconnected” Williams, probably sons of the other Moore men.

I was pulling my hair out.

The only way to even begin to straighten this out is deeds that include neighbors, waterways, court records and tax lists. Plus, a couple Williams had the decency to die with a will – but not mine of course.

Worse yet, the descendants of an “unrelated” James Moore, also from Amelia County, today live on the land that my James and William Moore lived on in the late 1700s and early 1800s. I say “unrelated” because the Y DNA tells us that they don’t share a paternal Moore ancestor, but I’m not entirely convinced they are in fact “unrelated.” More about that in James Moore’s article, yet to come.

I’m able to somewhat separate my particular William Moore from the other Williams because my William, after moving to Halifax County with his father, James, never moved again. He always lived in the same location, the Second Fork of Birches Creek, on land that is now the Vernon Hill community at the intersection of Oak Level Road and Highway 360, also known as Mountain Road.

Before I introduce you to my William, let me tell you who he is not.

The Wrong Williams

These men are NOT my William Moore. I compiled an embarrassingly large “every name” spreadsheet of every Moore person I could find in colonial Virginia with the assistance of Joyce Browning’s excellent extractions before she retired from active genealogy. This means that if there is a land sale with a buyer, seller and 4 witnesses, there are 6 entries in my spreadsheet for this transaction, which is also indexed by location and waterway.

Needless to say, the Moore family was not isolated, and the Combs, Rice and Estes families took the same migration path from eastern Virginia to Halifax County, more or less, so their records are contained in this same 25,000+ row spreadsheet. By the middle to late 1700s, these early colonial families had been intermingling and intermarrying as they pushed the westward frontier for 5 or 6 generations.

Yes, it was a miserable exercise BUT, BUT and this is very important, without that effort, I would never have been able to sort these families. In some cases, I still can’t entirely.

These 4 William Moores who are also found in Halifax County in the 1700s and the early 1800s are NOT my William.

- William (1) Moore born between 1712-1715 and died in Halifax County in 1786. He was living there as early as 1767 according to the vestry processioning notes. He lived on (Little) Cherrystone Creek and had a wife named Prudence who predeceased him. He is somehow connected to Robert Wooding. His children were Lucy Anna Moore who married John Echols and lived in Lunenburg County, Elizabeth Moore who married a Rowlett, William Jr. who lived in Pittsylvania County and probably married Sarah Hill. William lists grandchildren in his will, was wealthy and had an extensive probate.

- William (2) Moore born between 1770-1780 lived on Catawba and Childrey Creeks on land purchased by his father, Thomas who lived in Cumberland Co., VA in 1804. In 1829, William and his son William G. along with sons Wesley and Barnett were acquitted of assault. William (2) was declared a “lunatic” in 1833 and died in 1834 with a will. He had wife Mary, children; Harriett who married Thomas E. Moore, a hatter, who MAY have been the son of my William Moore or possibly a son of Daniel Moore, but there is no proof. (I’d love a Y DNA test from this line.) Harriett and Thomas sold their interest in William (2) Moore’s estate in 1834 from Charlotte County, next door to Halifax. William (2) also had son Barnett B. Moore born 1794 who married Lydia Booker and died in Greenbrier, WV, William G. Moore who married Virginia Taylor, Thomas P. Moore who married Susan Daniel, John W. Moore who was alive in 1834, Mary Moore who married a Taylor, Elizabeth Moore who married Donald Murphy and Jenetty Moore who married Griffin Toombs. There is no known Y DNA test from this Moore line, but I suspect there may be a relationship with my William Moore family. In addition to the possible marriage, Isaac Medley was William (2) Moore’s estate administrator and was involved with my William as well, both as a neighbor and the man who foreclosed his property. On the other hand, Isaac Medley was a wealthy land speculator and seemed to be involved with everyone.

- William (3) Moore married Rhoda Archer Powell in August 1802. His estate was probated in by 1804 in Halifax County. If they had a child, it was a female. This William may be the William associated with the Hugh Moore group.

- William (4) Moore alive in 1775 who accepted a slave in payment of his wife’s share of her father, James Hill’s estate. I believe they lived on or near Wynne and Terrible Creeks in Halifax County.

While these aren’t my William Moore, it’s certainly possible that some of these men are related to my William Moore and if the Y DNA were be tested of Moore males who descend from these lines, we would be able to prove or disprove it – breaking down brick walls for all parties. There’s also an early Daniel and Thomas Moore who may be related. I have a DNA testing scholarship for any Moore male who descends from these lines. If any of these are your lines, leave a comment on this article, please!

My Guy – The Reverend William Moore

The Reverend William Moore was one of the earliest Methodist Ministers in the US, even before the Revolutionary War, and in particular, Virginia. He was such an interesting man and quite well traveled for a humble Virginia colonial farmer. Of course, most of his travels were on the back of a horse plodding through all kinds of weather on his way to meeting houses carrying his Bible in his saddlebag. He began as a circuit-riding preacher.

William Moore was born about 1750 in Amelia County, Virginia near Saylor Creek, the part that would become Prince Edward County in 1754. His parents, James Moore and Mary Rice lived beside her parents Joseph Rice and his wife Rachel, so William grew up beside his grandparents, at least until they pulled up stakes, packed the wagon and set off for greener pastures about 75 miles away.

Back then, 75 miles was a far distance. William may never have seen his grandparents again.

By 1770, the Moore family had moved to Halifax County, Virginia where on January 7th we find a deed from James Spradling and his wife, Mary, to James Moore for “238 acres on the branches of the second fork of Burches Creek whereon the said Moore now lives being a part of a patent to said Spradling dated Sept. 16, 1765.” This deed was witnessed by George Stubblefield. The Moores had a generations-long relationship with the Stubblefield family and may have already been related.

Halifax County Tax Lists

Before the 1790 census, thank goodness we have Halifax County tax lists, at least partial rolls for some years.

William Moore first appears on the head of household list in 1782 with a total of 6 “white souls.” Given that 2 are he and his wife, that leaves 4 children born over approximately 8 years, plus one year before the birth of the first child and 1 year for maybe 1 death puts the marriage of William and Lucy at about 1772. Subtracting 21 years from that puts William’s birth at about 1750 or 51, or earlier. We know William died in 1826, which would have made him about 77. Lucy lived for several more years.

In 1783, a personal property tax list was taken that tells us that William had one horse and 2 cows and in 1784, he is taxed with 100 acres “from last year.” By 1784, he is up to 7 cattle and in 1785, he has 7 household members, so another child has been born. William continues to be taxed on 100 acres of land, even though he hasn’t purchased any yet, according to the deed books. As a “renter,” he is likely responsible for the taxes on the land he cultivates.

In 1788, he has 2 horses but in 1789 and 1790, only 1. Unfortunately, the 1790 census for Halifax County is missing as is 1800 and 1810.

By 1792, William has 2 horses until 1795 when he has one again but in 1796, back to 2. I suspect he is breeding a horse and selling the colt, but that’s just a guess.

In 1794, William begins being taxed on 170 acres.

In 1797, William is listed as exempt from taxes. There are very few reasons for this to occur:

- Advanced age (70 at that time in Halifax County)

- Disability (authorized by the court)

- A minister

- A sheriff or official

Granted, William was a minister, but not an Anglican minister. Never before had he been listed as exempt from taxes. His father, James, had been exempt every year since 1791, likely due to advanced age. I think James was born by 1721, so the fact that he was exempt in 1791 would seem to corroborate that.

William is not exempt in 1798, but is again in 1799.

If William was exempt because of age, he would have been consistently exempt from 1797 on, but he wasn’t. Something happened to William in 1796 or 1797, which is also the same time that he stopped submitting marriage documents to the Halifax County Clerk to be recorded.

In 1798, William is listed with 170 acres +100 acres from R. Dayelle. Is this really Ransom Day?

In 1799, William has a total of 300 acres listed as follows:

- 100 from James Moore

- 100 from same

- 100 from Ransom Day

In 1799 and 1800, William is back to one horse but has 2 again in 1801. The 1801 tax list says nothing about being exempt.

In 1802, William is taxed on 200 acres of land and that correlates with the sale of the 100 acres that he bought previously from Ransom Day. He has 3 horses that year and he is exempt again. He has 3 horses in 1803 and 1804, but 2 in 1805.

William continues to be exempt until 1806 and 1809 when he is not listed as exempt and has 4 horses. He is once again listed as exempt in 1810. After that, the tax lists are different and only provide the number of acres which continues to be 200 acres on the Second Fork of Birches Creek for William.

In 1812, William begins to be listed as William Sr., indicating that another, younger William has emerged, likely his son.

I can’t tell all of the William Moores in the county apart, so we don’t know when or if William’s son William joined the tax list. Both William and his brother Azariah married and settled in Pittsylvania County.

Azariah shows up on the tax rolls in 1804, meaning he would have been born in 1783 or before. He was a veteran in the war of 1812. His death was recorded in Pittsylvania County, but unfortunately his mother’s name is not provided.

1816 is the last year that we have tax lists for this time period. William is missing entirely from the 1820 census. The only possible William Moore that could be him is not living among the neighbors where I would expect to find him and has a slave. Given what I know about William, I’d be very hard-pressed to believe that William is mine. I think he was either missed or is at the bottom of a census page that managed to get cut off. Looking at the schedule, that’s exactly where I would expect to find him, based on his known neighbors.

Dissenters!

The Rice and Moore families were early dissenting families in Prince Edward County, meaning they did not belong to the Anglican Church. Initially, these dissenting churches were illegal, but eventually, after the Revolutionary War, each county was grudgingly allowed to have 2 or 3 “dissenting ministers” who had to be ordained and to register with the county who would then license them to perform marriages and other ministerial functions.

The requirement for ordination served to severely limit the number of requests, as ordination implied some sort of formal training and interacting with the upper echelon of the church, not just being inspired, jumping on a tree stump and preaching to your neighbors.

Joseph Rice, William Moore’s grandfather, is recorded in 1759 as having built a meeting house for a dissenting religion in Prince Edward County, so we know that William Moore was raised in a “dissenting” household. This is very probably why William’s marriage to Lucy was never recorded in the records of Halifax (or Prince Edward) County, as their marriage was likely not performed by a minister from the Anglican Church. In 1770-1775 when they would have married, the provision for dissenting ministers to be licensed had not yet been incorporated into law, so their marriage was technically nonexistent.

Another possibility is that marriage records are missing in Halifax County for the Revolutionary War years. They could have been married and the return filed, only to be subsequently lost.

Unfortunately, because that record doesn’t exist today, we don’t know Lucy’s last name.

The Early Methodist Church

William Moore is particularly interesting because of his, at that time, revolutionary religious ideas, and his passionate renderings of them.

The Methodist church had its roots in England. Francis Asbury volunteered his service to America in 1771, and in 1776, when the Revolutionary War broke out, he was the only Methodist minister to remain in America. The rest, along with many Anglican ministers as well, returned to the safety of England. While the Methodists often received the sacraments from Anglicans, now that option no longer existed.

Seeing the problem of the lack of ministers, Asbury set about finding American men to recruit as circuit riders. He had a problem however, in that ministers at that time had to return to England to be ordained, something colonial men were not interested in doing, nor was it practical, especially not in wartime. Asbury continued his work as best he could with the resources he had.

The Methodist Church in the colonies was a fledgling organization. The 1784 Christmas Conference, held a few years after the American Revolution, in Baltimore, Maryland, was a historic founding conference of the newly independent Methodists within the United States

By November 1784, it had become evident that the American Methodists were to be granted some level of freedom from the English Anglican Church Methodist societies, and Thomas Coke was to ordain Francis Asbury as the first American Bishop at the Christmas Conference.

Eighty-three itinerant ministers were eligible to attend that conference, and of those, 60 were present, including William Moore. This record is preserved in a painting of the historic event. Unfortunately, William is too far to the rear to be seen clearly, but he is individually identified.

One possible fly in the ointment is that a different William Moore who lived in Baltimore was known to be associated with Francis Asbury, but the William Moore from Halifax County was close to another minister at that conference by the name of James O’Kelly. My ancestor, William Moore, is known to be the man who founded a church in Halifax County with O’Kelly.

We will never know for sure if the William Moore in the painting is mine from Halifax County or the William from Baltimore. For now, I’m going to assume it was my William because of his association with O’Kelly and his level of commitment to the Methodist faith.

The 1784 Christmas Conference

The famous “1784 Christmas Conference” in Baltimore, Maryland, convened on Christmas Eve, where Francis Asbury was ordained by Thomas Coke by the authority of John Wesley. This signaled the beginning of the organized Methodist Church in America, separate from England. At this conference, itinerant preachers gathered from the frontiers where they were circuit riders. Over a six-week period they prepared for the meeting and they were all present for the historic ordination of Asbury on Christmas Day along with 12 additional ministers who were ordained, setting the precedent that ministers were ordained in America at the Conference.

This wood carving of a painting shows the ordination of Asbury by Coke, with the legend prepared, below.

This is the best rendition we have of William Moore if this is our William.

William’s son, Azariah, was described by his widow in her War of 1812 pension application as having had black hair, blue eyes and a red complexion.

William is described in “The Lives of Christian Ministers” as follows:

REV. WILLIAM MOORE became an itinerant preacher among the Methodists in 1778 and continued three years having located in 1791. He was at the Conference in 1779, as also was O’Kelly, and was one of the preachers that approved the appointing of a presbytery and the giving of the ordinance to the people. This Conference was regular in its appointment and had plenary powers. It appointed a presbytery to ordain its preachers and authorized the administration of the ordinances. The answer to the question, “What mode shall we adopt for the administration of baptism?” was “Either sprinkling or plunging, as the parents or adult may choose.” Whether dissatisfied with the circuit assigned him, after Mr. Asbury came to the Conference, we know not. He was admitted however while Asbury was under the protection of his friend Mr. White’s roof in the state of Delaware. After Mr. O’Kelly’s withdrawal, he united with him in his labors, and attended the General Meetings. He attended the Conference or General Meeting at Shiloh in Halifax county, Virginia, in 1805, and served on the presbytery of ordination. Up to this time he had been a minister more than thirty years.

The interesting thing about the above passage is that the 1805 date and the 30 years comment combined indicate that William became a minister before 1775. Also interesting is that William became a minister before the Revolutionary War, while Asbury was taking shelter from the War and not traveling to preach.

This begs the question of when William was ordained. Did he travel back to England, or was he ordained in the US?

To understand this issue of circuit assignments, it helps to understand how the Methodist religion worked at that time since there were very few ministers. The following graphic is from “Life of Rev. James O’Kelly – Christian Church in the South – Restoration Movement.”

In essence, this ruckus was caused because ministers who did not like where they were assigned had no avenue to appeal. Keep in mind that most of these ministers were also farmers. Many were not paid at all, so being absent from one’s farm for long stretches could have devastating financial and family implications.

Not only did William witness history being made at the 1784 Conference, he was part and parcel. While William Moore didn’t leave us a journal, we’re fortunate that O’Kelly, who was friends with Thomas Jefferson, wrote, Asbury wrote and the church that O’Kelly and William Moore founded recorded their history!

Let’s take a look at what they tell us.

Later Conferences

William likely attended state conferences as well in order to participate in the functioning of the church and commune with the other ministers.

In 1786, the Virginia Conference met at Laine’s Chapel in Sussex county. In 1787, the Conference in Virginia was held at the Rough Creek church in Charlotte county across the Staunton River from Halifax. In 1781 and 1789 the Conference met in Petersburg.

By 1791 William was no longer attending the Methodist Conference, having “located”, meaning he was no longer itinerant, according to the Methodist Church archives, and was assigned to a church.

This is probably the period when the Moore Meeting House in Halifax County, Virginia, where William lived, was established, even though William Moore didn’t own that land.

The Methodist Church couldn’t explain why William didn’t have an obituary on file, but I solved that mystery.

Dissenting Again – A New Methodist Church

At the Baltimore Conference held November 11, 1793, the Rev. James O’Kelly and his immediate cohorts, which likely included our William Moore, withdrew from the Conference after a disagreement with Bishop Asbury (possibly over slavery, which Kelly and Moore vehemently opposed) to establish the “Republican Methodist Church.”

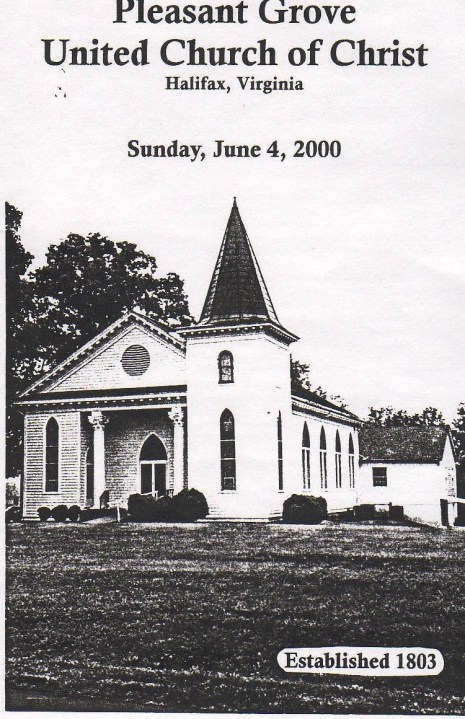

In 1801, the name was changed to “The Christian Church” and in 1803 they founded what is today the Pleasant Grove United Church of Christ in Halifax County, just down the road three and a half miles from where William lived.

William’s Ordination

In 1805, William Moore with James O’Kelly together attended the Conference or General Meeting for their new religion at Shiloh in Halifax County. William Moore served upon the presbytery of ordination at that event and was recorded as having been a minister more than 30 years, which dates his preaching career to before 1775.

We don’t know exactly when William Moore was ordained, but if he did not go to England, then I wonder if his ordination was “made official” at the 1784 Christmas Conference because the next general Methodist conference was not held until 1791 or 1792 and then every 4 years afterward.

William is recorded as having filed a marriage return with the county clerk in 1786 and produced his ordination papers in court in 1789. We know that he was present at the 1784 Christmas Conference where 12 ministers were ordained. If he was ordained earlier, it’s unclear how that could have happened unless he traveled to England for his ordination or was unofficially ordained by the other ministers. If that had happened, then how would he have had ordination papers?

What I wouldn’t give for a copy of those ordination papers submitted to the court or William’s probably threadbare copy of “The Sunday Services of the Methodists in the United States of America,” written by Wesley, typically presented to ministers at the time of their ordination.

The following quote about William Moore from “The Lives of Christian Ministers” hints that he may have been ordained during the Revolutionary War and before the Christmas Conference in 1784. When the War broke out, Asbury stopped circuit riding and took refuge in Delaware in the home of Mr. White and did not return to circuit riding until immediately following the Christmas Conference in 1784.

“Whether dissatisfied with the circuit assigned him, after Mr. Asbury came to the Conference, we know not. He was admitted however while Asbury was under the protection of his friend Mr. White’s roof in the state of Delaware.”

So if not Asbury, then who “admitted” William Moore?

According to Asbury’s transcribed notes, on page 381, in a footnote, he states that in 1778, at Broken Back Church in Leesburg, VA, the following questions were asked:

Ques.: What are our reasons for taking up the administration of the ordinances among us? Ans.: Because our Episcopal Establishment is now dissolved, and, therefore, in almost all our circuits the members are without the ordinances.” Eighteen preachers approved. They were Isham Tatum, Charles Hopkins, Nelson Reed, Reuben Ellis, Philip Gatch, Thomas Morris, James Morris, James Foster, John Major, Andrew Yeargin, Henry Willis, Francis Poythress, John Sigman, Leroy Cole, Carter Cole, James O’Kelly, William Monroe (or Moore, Lednum, op. cit., 280), Samuel Roe. Other questions were: “What form of ordination shall be observed to authorize any preacher to administer? Ans. By that of a presbytery. Ques. Who are the presbytery? Ans. Philip Gatch, Reuben Ellis, James Foster and in case of necessity, Leroy Cole. What power is vested in the presbytery by this choice? First to administer the ordinances themselves; second, to authorize any other preacher or preachers, approved by them, by the form of laying on of hands.

Asbury disproved, but it happened nonetheless.

Was this “approval” William’s ordination? This 1778 date correlates with the information provided in the “Lives of Christian Ministers.” William could have been preaching prior to 1778 before being ordained.

According to the History of Methodism in the US discussing the American Revolution:

Up until this time, with the exception of Strawbridge, none of the missionaries or American preachers was ordained. Consequently, the Methodist people received the sacraments at the hands of ministers from established Anglican churches. Most of the Anglican priests were Loyalists who fled to England, New York or Canada during the war. In the absence of Anglican ordination, a group of native preachers ordained themselves. This caused a split between the Asbury faction and the southern preachers. Asbury mediated the crisis by convincing the southern preachers to wait for Wesley’s response to the sacramental crisis. That response came in 1784.

Was William one of the self-ordained ministers? What the 1784 answer to officially ordain William Moore at the Christmas Conference?

It’s known that William Moore and James O’Kelly were fast friends. In 1786, O’Kelly was assigned to preside over the circuit that included Halifax County.

William Moore produced his ordination papers in court in Halifax County, VA in 1789 and was licensed as one of the 3 “dissenting ministers” allowed to each county after the Revolutionary War. In order to qualify, each minister had to produce their ordination papers and then they were licensed to perform marriages, baptisms and other ministerial functions.

Most importantly, they could register the marriages they performed. We know that William was marrying people in Halifax before this date, at least as early as 1786 when he married Bolling Hamlett and Polly Combes and registered the marriage with the clerk of court, so his ordination was clearly prior to 1786, one way or another.

The Moore Meeting House and Neighborhood

William moved to Halifax County with his father, likely farming part of his father’s land for several years. William and Lucy were married by about 1772, so the marriage likely occurred in Halifax County sometime after William moved there about 1770.

The Revolutionary War and William’s circuit riding likely interrupted plans for land ownership, but in 1797, Ransom Day sold William Moore 100 acres on Polecat and Birches Creeks for 75 pounds, with the “meeting house excluded.” It’s worth noting that Thomas Moore witnessed this purchase, given that Thomas is believed to be one of William’s children, perhaps his eldest. If Thomas Moore was not William’s son, Thomas was probably William’s youngest brother.

William and Lucy owned this tract of land until 1801 when they sold it to Arthur Slaton, again, excepting “where the meeting house stands.” They couldn’t sell what they didn’t own.

Two of William’s daughters married Slayte/Slate men.

In deeds later in the 1800s, the meeting house is referred to as the “Moore Meeting House” even though William never officially owned it.

In 1798, James Moore sold 200 acres for 65 pounds on the Second Fork of Birches Creek to William. Thomas Moore witnessed that transaction too. The Ferguson family, neighbors with whom an alliance from Amelia County is suspected, along with Henderson family members served as witnesses.

William Moore’s 1797 land purchase from Ransom Day, “meeting house excepted,” today includes the land where the Vernon Hill post office is located, a contemporary brick house and probably the white house to the east as well.

William’s property included the land where the Mount Vernon Baptist Church is currently located, directly across the road from the brick house which is the parsonage.

On the map below, the red arrow points to the Mount Vernon Baptist Church which did not exist when William Moore owned this land.

Where star #1 is placed is the original location of the Moore Meeting House, and star #2 marks the location of an old abandoned cemetery, probably permanently lost to time by now.

The person who took me to the old cemetery probably 15 years ago told me that when he was a child, they played in the cemetery, but recently backhoes and bulldozers had all but obliterated what was left. There were at one time “old stones” but none were either there or readable when I visited. True to form, Yucca plants and Periwinkle revealed that this location had once been a burial ground, even though when I visited piles of logging debris were pretty much all that was left.

I doubt this is where William and Lucy are buried, given that this land was sold in 1801. Assuredly, William preached funerals in this forgotten cemetery though as his neighbors were laid to rest.

The cemetery across the road beside the Mt. Vernon Church did not exist in 1909 when the land was split between the heirs of Mrs. I. C. Saterfield who inherited the land from her father, an Anderson. The cemetery was founded in 1936, so William clearly isn’t buried here either. He’s probably buried on the land owned by his father, James, located just to the south.

At one time, pretty much all of this land was owned by James Moore, William Moore or Edward Henderson. Today, the land south of the intersection of Mountain Road (360) and 683 (Oak Level), on the west side of the road is owned by the Henderson family. The old cemetery, probably shared between Edward Henderson and his father-in-law, James Moore is located approximately where star #3 is placed.

We’re fortunate that after William’s death in 1826, Lucy contested William’s 1822 transaction which resulted in him losing their land and sued for her share of the property. She won and the court ordered a survey which was included in the chancery papers.

The acreage doesn’t exactly add up to 200, so clearly either the entire tract does not equal 174 acres, or 25 acres were split earlier and never recorded.

William’s land is probably where the Mount Vernon Baptist Church stands today, given that in 1851, Lucy’s land is referenced as being directly across the road from the Vernon Meeting House. The Vernon Meeting House was originally the Moore Meeting House, located on the north side of the road, probably renamed when the original building was torn down and a “new” one constructed in its place.

Across the street from today’s church where the parsonage stands is where the original Moore meeting house was located, surrounded by William’s 100 acres that he bought from Ransom Day, “excepting the meeting house,” as shown in the photo below on the north side of Mountain Road.

Researching this land further, the deeds explicitly mention the headwaters of Polecat Creek which originates on this piece of land. The deed also mentioned the waters of Birches Creek which is on the south side of the road, so William’s 100 acres spanned the road.

Furthermore, the minister at the Mt. Vernon Baptist Church explained the church’s history, indicating that the “original” church was on the north side of the road in the 1800s, which is confirmed by various deeds.

The headwaters of Polecat Creek are behind the dog house, which sits where the old Moore Meeting House used to be. I can see the church-goers wandering to the stream after the sermon to drink from the gourd dipper shared by all.

Apparently, the “Moore Meeting House,” as it would come to be called, was the predecessor to the “original” Mt. Vernon Baptist Church that was built on the north side of the road and torn down after the church on the south side of the road was built in the early 1900s.

Looking to the east of the original meeting house location today, we see an old house which probably dates to the 1800s, but not from the early 1800s. Those would have been log cabins.

This home with its old barn is beautiful and likely stands on the 100 acres that William once owned.

In 1801, William Moore and his wife Lucy sold this land “except where the meeting house stands.” In deeds as late as 1854 references are made to both the “lines of Lucy Moore” which apparently intersected with this land across the road and where the “old Moore Meeting House” stood.

Buildings in Halifax County aren’t replaced because they are old. They are simply re-appropriated for something else. I surely wish the old Moore Meeting house still existed. It was probably a small log cabin that was built sometime before 1790 was torn down in the 1800s.

I love these old buildings. Many of the original cabins were turned into barns and are still in use.

Driving south on 683, Oak Level Road, William’s land is stunningly beautiful. The land here is gently rolling and occasionally, rocky.

The back side of the Moore land is 663, also known as Carlbrook Road. Although the road is paved, it probably resembles the region when William first settled here and began to clear the trees to farm.

William’s fields. James Moore bought land that had just been patented, so no fields would have existed then. James and William cleared the land for farming. Back-breaking work.

Houses are visible, scattered widely, in the distance. Many structures date from the 1800s and some even earlier. I believe this is the old Henderson property, above.

Historic structures peek at you from fields and woods, whispers from the past.

A misty morning on Oak Level Road, I wonder if William would recognize his land today?

Just down Mountain Road, slightly west of High Point Road, we find a place the locals call Top of the World. Looking north, you can see for 50 miles to the Peaks of Otter in the distance.

All can say is that it’s a good thing that the one lot for sale along Mountain Road didn’t have a very good view, or I might be a Virginia resident today, following in the footsteps of William Moore. I was truly tempted.

Driving down the road, you can see timeless visages of yesteryear. Not much has changed except there are more fields and fewer trees.

What stories these old barns and houses could tell, if they could just speak.

Foundations were made of gathered stones, as were early gravestones.

Who lived here? Did William know them? Are they family?

Pioneers looked to settle on land with a fresh spring, assuring clean water that had not been contaminated by human or animal waste.

Soon the spring formed a little creek, like this one on the old Moore land

There’s every possibility that this log building stood when William lived. Given his role as a minister for half a century, comforting families in times of grief, he was probably in every home in this part of Halifax County at one time or another.

Road Hands

Road hand lists are invaluable sources of information. Episodically, the court would order certain “hands” to labor on the various roads, which of course were dirt and full of ruts at that time. Those lists tell us who the neighbors were. In 1801, we find this court entry:

Jacob Farguson surveyor from Martin’s Fork to County Line, hands James Farrell Jr. and Sr., Josiah Young, Exekiel Foulke, Frederick Ferrell, James Watson, Sherwood Watson, Edward Henderson, John Henderson, Hudson Butler, Arter Slayton, Hudson Farguson, William Moore, Robert Walton, Isac Wilson, William Womack, William Farguson, David Wilson, Richard McGrigor, Bartlett Chaves (listed twice).

Of these surnames, we know that the Fergusons lived in Amelia County when the Moore family did, Edward Henderson is believed to be William’s brother-in-law, Arthur Slayton bought land from William Moore and two of William’s daughters married Slayte men.

The most interesting aspect of this list is that somehow my DNA is connected to the Womack family through the Moore line. Not just once but matching roughly 30 descendants. This means there’s smoke and probably fire if I could just unravel the web.

We don’t know the surname of William Moore’s wife, Lucy, or the identity of 3 of William’s grandparents. Lots of opportunity for a Womack connection. The Womack family is also found in Amelia and Prince Edward Counties interacting with both the Moore family and the Rice’s.

There’s a story there yet to be told!

The Split!

Religion is nothing if not contentious.

The Rev. William Moore was apparently very close to the Rev. James O’Kelly. Both were probably at the Christmas Conference in 1784 where O’Kelly was ordained.

William was destined to split with the Methodist Church, and probably did so when his friend James O’Kelly left the church. William then participated in founding both a new religious sect and a new church.

On August 4, 1794, O’Kelly and his ministerial secessionists from the Methodist church met in Surry County, VA to organize and form their own church.

From the Pleasant Grove Church, a few miles east of the Mt. Vernon Baptist Church, I was provided with the following information:

At the end of the 18th century, and the Christian Church in America was only 6 years old. At this time Reverend James O’Kelly who had broken from the Methodist Church because of a dispute with Francis Asbury came into Halifax County, Va. preaching the Word. Finding a number of people attracted to his preaching and being interested in the new Church movement called “Just Plain Christian,” the Rev. O’Kelly proposed that a Christian Church be organized, and Pleasant Grove Church, just off Mountain Road, was organized by the Rev. O’Kelly in 1803.

In a flyer for their 197th anniversary, Sunday June 4, 2000, they indicate that their church was established in 1803 and that the first two ministers were Rev. James O’Kelly followed by Rev. William Moore. The first building was constructed of logs and stood just south of the present building. Unfortunately, their older church minutes no longer exist, having departed with one of the previous ministers.

The original building stood where the circular driveway is today, with the steps remaining in the center of the circle. In the photos above, they are to the right of the tree and resemble a pile of rocks. When I first visited, I was told that they left the steps so that the ladies could use them to mount horses or climb into wagons or buggies.

Motivation

Information about James O’ Kelly written by J.F. Burnett, Minister in the Christian Church, helps us understand the issues that motivated both O’Kelly and by inference, William Moore, to split with the Methodist Church.

The question as to whether or not preachers should be allowed to administer the communion, baptize candidates, marry people, and bury the dead, always found Mr. O’Kelly on one side, and the rule of the Church on the other. Bishop Asbury’s insistence that the laymen were to “pay, pray and obey” was always objectionable to Mr. O’Kelly and the divergence increased and the chasm widened, and the point of cleavage became more prominent, so that by the time the General Conference met in 1792 a crisis was inevitable. By this time too, Mr. O’Kelly had reached a high place in the favor of the church. He had presided over some of the largest and most important districts within the territory then occupied by the Methodist Church, and only two men out-ranked him in authority. He had, in all probability, accumulated means sufficient to put him above the necessity of salary and most certainly he had reached a well established leadership among his brethren. But it was not these that gave him prestige in the conference. It was his devotion to the right, his indomitable will, and his Christian courage. He would have been impressive had he been clothed in rags, and walking bearfoot. The craven had no place in his makeup, either as a man or a preacher.

On December 1, 1789 James O’Kelly sat in the body of the conference where the bishops proposed that a council of presiding elders be convened and strongly opposed some of the measures. Notwithstanding, Bishop Asbury, who was in favor of them, deemed it wise to call a second, but only 10 elders attended and a third was never held. O’Kelly labored heartily in favor of a general conference and to him the Methodist church owes “that essential and valuable constitutent of its polity.” He wrote letters to Thomas Coke, Wesley’s ambassador securing his cooperation, and in consequence bringing these two fathers of American Methodism to the verge of antagonism. Seeing that a crisis had been reached, which he could not prudently ignore, Asbury sacrificed his personal wishes and consented to the holding of a general conference. It was called for November 1, 1792 and O’Kelly introduced a resolution to modify the bishop’s power of appointment to the extent of allowing any preacher who should feel dissatisfied with the place assigned to him an appeal to the conference. This was rejected by a large majority and O’Kelly sent in his resignation and withdrew. Several of O’Kelly’s adherents also left the conference and he subsequently organized a “Republican Methodist Church,” afterward called the “Christian Church.” In 1829 it included several thousands in its membership, mostly in North Carolina and Virginia. O’Kelly focused his efforts primarily in Virginia where he oversaw the best circuits.

At one point, Thomas Coke reported that he had prevailed upon O’Kelly and “his 36 ministers” to remain within the church, but that was not to be. The split occurred and O’Kelly held conferences in his new group of churches.

William Moore was clearly one of O’Kelly’s band of 36 merry ministers.

The General Meeting for 1805 was held at Shiloh church on the line of Pittsylvania and Halifax counties. The presbytery appointed to ordain Rev. Thomas E. Jeter was composed of the following Elders: James O’Kelly, Clement Nance, Joseph Hackett, William Moore, and Coleman Pendleton.

The General Meeting of the Conference was held at Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1807 and 1808.

The General Meeting in 1809 was held June 4th at Shiloh, in Virginia, where O’Kelly preached at Apple’s chapel and administered the Lord’s Supper. Five other ministers were present. It’s likely that William Moore attended and based on the meeting locations, we can gain insight into what William was doing at that time. He traveled far more than most men of his generation.

In 1810, the General Meeting of the Conference was held at Pine Stake church in Orange County, Virginia. It was there that a division occurred due to a difference of opinion in respect to “the mode and subjects of water baptism, which led to the organization of the North Carolina and Virginia Conference.”

Mr. O’Kelly was a strong effusionist. In his book entitled “The Prospect before Us by Way of Address to the Christian Church,” he says, “But to illustrate the figures still further. The ark may be a figure of Christ’s Church; the family that entered into the ark and were saved so as by water, may answer as a figure of household baptism under the gospel dispensation.”

Translated, this meant that O’Kelly strongly preferred sprinkling as opposed to baptismal immersion, and he felt that the Father, Son and Holy Ghost were three separate literal beings, not one tri-partite Holy Being.

If O’Kelly held those beliefs, it’s likely that William Moore did too, given that they co-founded a new church in Halifax County in 1803.

1811’s Virginia Conference was held in Caroline County. As it pertained to religion, it’s a safe bet that William Moore and O’Kelly were probably at the same conferences as long as both attended.

O’Kelly died in October 1826, the same year as William Moore. It’s a safe bet that those two men reunited on the other side!

O’Kelly published pamphlets and books throughout his life, including a hymnal. Reading O’Kelly’s writings would probably enlighten William Moore’s descendants about his beliefs as well.

Slavery

Another influencing factor in the split from the Methodist Church may have been O’Kelly’s strict opposition to slavery. He was known as a “heroic opposer of slavery and enforced the anti-slavery law of the church.”

Francis Asbury stated in his “Journal,” volume 1, page 384, “Brother O’Kelly let fly at them (about slavery) and they were made mad enough.” In 1789, O’Kelly published his Essay on Negro-Slavery after having manumitted his only slave in 1785.

William Moore did not own slaves, nor did his father nor most of his children. Ironically, his refusal to participate in that wicked institution may have contributed to his financial issues that resulted in losing his property.

I get the sense that William Moore was a very strong, very determined man.

William’s Trail

In 1782 and 1799, one William Moore signed petitions protesting the glebe land provided to the ministers of the Anglican church. I don’t know if my William was the one who signed, but it would make perfect sense that a man who received no benefits from the Anglican church wouldn’t want his tax money to provide a farm for their minister. William certainly didn’t get a farm paid for by the government. In fact, the petition William signed was to sell the glebe land.

It seems that perhaps William Moore’s strength wasn’t paperwork. A loose paper filed in the Clerk’s office in Halifax County shows that William “saved” the records of 5 different couples between August of 1790 and March of 1791, writing a single note to record all 5. The good news is that this is clearly his own handwriting.

William married dozens of people between 1786 and 1797 when the records abruptly stop, which of course suggests that these couples were also dissenters or members of dissenting families. That makes sense, because at least 3 families have connections in some way to the family of John R. Estes who William’s daughter, Ann Moore, known as Nancy, married in 1811.

The marriage records found at the courthouse may have stopped because when William withdrew from the Methodist religion, he also lost his official “blessing” as a dissenting minister. That didn’t stop him from preaching, and I doubt it stopped him from marrying people either. It certainly didn’t stop anyone from being buried or baptized!

As a minister and respected member of the community, William was peripherally involved in many lawsuits and transactions, typically as a witness. I’m sure as a minister, his testimony was fairly unimpeachable. Probably the most interesting of these cases were the ones for hog-stealing and slander where Edward Henderson (probably his brother-in-law) alleged that someone was “drunk and out of humor.”

William didn’t avoid lawsuits entirely though. In 1795, Uzza Pankey sued William Moore for slander and in 1796, William sued Benjamin Huddleston, Usse Pankey and Stephen Pankey. We don’t know the outcomes, but the Pankeys were neighbors and William had performed the marriage of one family member. William Moore and the Pankeys shared a property line, so life must have been interesting during this time.

I’d love to know what the slander suit was about. Looking at William’s 1819 deposition, he didn’t mince words.

No matter the century, there’s always neighborhood drama.

In 1796, the overseers of the poor bound John Chambers, the son of Sarah Chambers to “William Moore, preacher.”

In 1797, William Moore was a witness for Isaac Medley against Bolling Hamlett, whose wedding William had performed. Isaac Medley is an important figure in William’s life, so stay tuned.

In 1813, William Moore, along with Azariah are found with “effects insufficient to pay taxes,” but this William mentioned could be William’s son, William.

In 1812, 1813 and 1814, Azariah and William are deputy sheriffs, but I suspect this record pertains to the younger William Moore.

In 1814, William is sued for debt, twice. Early Virginia was very litigious.

In 1815, William Moore is taxed for his 200 acres on the Second Fork of Birches Creek, so we know how much land he owns.

Drunk or Insane

The most humorous document was an 1819 chancery suit regarding a wedding over which William presided in 1817 where he opined that the groom was either drunk or insane, but let’s look at William’s own words.

Deposition of William Moore in the suit between Isabel Dodson and John Dodson…Reverend William Moore saith that:

“on the 4th day of July 1817 I was sent for to marry a cupple in Milton (NC). There were a number of people collected together about the tavern. I took a seat in the Pizza and asked who was to be married. Some person replied “you’ll see directly” and in a very quick time John F. Dodson led Isabel Baines to the Pizza (probably piazza). I asked him for his license, he said he had them, and some person replied “you have them not” but that Thomas Turner who has them who had gone up to Jack’s Woods Tavern for dinner. I then told Dodson that he might lead back his bride until I got the license and he said so. I saw Thomas Denaho and he delivered me a lawful license. I then walked into the room the noon? and told him I was ready to wait on him, he led up his bride and I married the pair. I then took a seat in the pizza, there was a decanter of spirits setting on the shelf, he asked me if I would take a drink of grog and I told him no, he then took a drink and pulled out a red morocco pocketbook and gave me a dollar. In the time that I was performing the ceremony he said something it set the poeple a laughtin (sic) but I did not hear what it was that he said. I concur him to be in a state of intoxication at the time of the marriage or in a state of insanity. I have been acquainted with him for several years and I always considered him a person of weak intellects.”

Sworn October 19, 1819 William Moore (signed.)

William certainly didn’t pull any punches. I’d wager the entire Dodson family, some of whom also lived on the Second Fork of Birches Creek, were permanently aggravated with William.

Debt

In 1820, there were 2 debt cases, one by and one against William Moore, but we can’t tell based on the little information we have which William Moore was involved.

In 1824, William Moore signed a debt document.

By this time, William’s signature was quite shaky. He would have been on the north side of 70, probably 75.

This signature really makes me wonder. My presumption was that it was shaky because William was elderly, but the signature on an 1825 document looks quite different.

Another debt was incurred by William in 1825 as well and he conveyed to William Minor a deed of trust for 50 acres of his land.

In 1827, “James Young of Halifax County to Isaac Medley of Halifax whereas William Moore by a certain indenture bearing date March 26, 1822 did convey to James Young a tract of 200 acres bounded by the lines of Joseph Dunman, estate of Jacob Farguson, Jane Wilson, James Moore and Edward Henderson Sr. as described in said deed. James Young did expose to sale on November 25, 1825 and sold for $200 to Isaac Medley.”

On March 4th, 1827, William’s land was conveyed by trustee to Isaac Medley.

The conveyance does not say that William is deceased, but we know that by November 1826 William had expired because Lucy’s suit states that “sometime in the current year her husband William Moore disposed of some land to Isaac Medley for debt but that Lucy never conveyed her right of dower. William subsequently died.” The court ordered Lucy’s dower portion surveyed and she received 50 acres that included the mansion house.

Mansion house at that time meant main dwelling. I’ve seen descriptions of mansion houses that were 10X14 or 12X16, so not a mansion as we think of them today.

The Tobacco Lawsuit

A suit filed in Halifax County chancery court in 1825 reached back to 1812. In this suit which is clearly our William, based on both the other witnesses and the fact that he is referred to as the Reverend William Moore, he files suit regarding 1360 pounds of tobacco which was valued at $5 per hundred pounds which would be $68, a lot of money at that time.

The original company went out of business and was purchased by William Baily. William Moore alleges that he was never credited with the amount he was owed which was supposed to have been credited to his account.

In this suit, William appeared before the clerk on October 20, 1825. On March 12, 1825, William Henderson stated that he went to Manchester, VA with Reverend William Moore where the tobacco was inspected at Johnson’s warehouse and the amount of $5 per hundred was offered.

On February 25, 1825, William Moore notified William Bailey of the time and location that William Moore Junior and William Henderson were to be deposed at the homes of Nathaniel Wilson in Dansville, VA and at the house of William Minor, respectively.

William signed this notice, shown below.

I wonder if someone wrote and signed this notification for William. It surely is not the signature of the same person who signed in 1824 with palsied writing.

We have additional signatures of William Moore when he signed for his daughters to marry.

Kids and Marriage

The known children of Rev. William and Lucy Moore:

- Thomas Moore was born between 1771 and 1777, taken from the 1792 personal tax data. This is probably the Thomas who married Polly Baker in 1798 given that his granddaughter’s middle name is Baker. Thomas died in 1801 leaving orphans Rawley and William who were bound by the overseers of the poor to Anderson Moore who had also come from Prince Edward County and bought land from Nimrod Ferguson near James and William Moore. However, the Y DNA of one of Anderson’s Moore descendants doesn’t match the William Moore line DNA. In the 1840 census, Raleigh Moore is living beside Edward Henderson.

Raleigh is buried in a cemetery in a very overgrown clump of trees (above) on his land (below) at Vernon Hill where he also maintained a tavern.

- Elizabeth Moore born between 1770-1780. She apparently winds up with her mother’s land and doesn’t marry.

- Azariah Moore was born in 1783 or before and served in the War of 1812, dying in 1866. He married Letitia Johnson in 1818 in Pittsylvania County, having four daughters and two sons. Letitia’s father left her money but stipulated that Azariah couldn’t touch it, nor could it be used to pay his debts of which there seemed to be many. According to the census, one son apparently died young, but James F. Moore who was born in about 1822 survived. In 1880 we find Letitia S. Moore age 79 living with her son James F. Moore, age 58. It appears that James never married, or he married after his mother’s death sometime after 1880.

- William Moore, born 1775-1785, moved to Pittsylvania County before 1815 and had business dealings with his brother, Azariah. William probably married Sarah (or Sally) and had at least 2 sons and 3 daughters. By 1850 William had died, but his wife Sarah was shown as age 64 (which could be in error) along with Nancy Jenkins age 36 (born about 1814), Sarah Jenkins age 11 (born about 1839) and a son William Moore born about 1820, age 30.

- Ann Moore, known as Nancy, born about 1785 married John R. Estes on November 25, 1811 and moved to Claiborne Co., TN about 1820 where she died between 1860-1870.

- James Moore born about 1785 married Lucy Akin in 1817, lived beside Edward Henderson in the 1820 census and was dead before 1830 with no known children. In 1827 James lost his land by debt to Isaac Medley, the same man who purchased William Moore’s land the same year. By 1831, Lucy Akin Moore, James Moore’s widow, had married James Ives.

- Kitty Moore born about 1788 married Francis Slate in 1805 and lives in Surry Co., NC in 1850.

- Jane Moore born about 1803 married James Blackstock in 1823.

- Rebecca Moore born about 1805 married William G. Slayte (Slate) in 1825.

Note that William Slayte is the same person (or at least the same name) that signed the debt document with William Moore in 1824.

Possible additional children of William Moore:

- Lemuel born before 1791, perhaps as early as 1770-1780, appears in 1812 on the Halifax County tax list. In 1830 we find a Lemuel in Grainger Co. TN beside Mastin Moore, known to be a grandson of William’s brother. Sometimes Lemuel is written as Samuel. Furthermore, a Lemuel Moore married Anna Stubblefield in 1804 in Grainger County and died in 1859 in Laurel County, Kentucky. In 1797, Lemuel Moore is found in Greene County, TN beside Rice Moore, William Moore’s brother. I have DNA matches through 3 of Lemuel’s children at what would be (1) 4C1R, (2) 5C and (4) 5C1R if the Lemuel in Laurel County, KY is indeed William’s son. If that Lemuel is more distantly related, the relationships would be more distant. The connection could also be through the Stubblefield line, which may be connected through either William’s wife, Lucy, or William Moore’s parents.

- Isaac born in 1793 or before, assigned as a road hand in 1814 with James Moore and Samuel (Lemuel?).

- Israel born in 1791 or earlier, appears 1 time on the tax list in 1812 the same day as William.

- Mary Moore born in 1775, found in 1850 census living with William B. Moore (the orphan of Thomas Moore and brother to Raleigh Moore).

Foreclosure

By 1820 William was encountering financial difficulties. He would have been in his 70s by this time and probably less likely to preach. His income while not completely dependent on preaching was probably affected somewhat.

William took a loan using his land as collateral in 1822. He was unable to repay the loan, and his land was deeded to Isaac Medley by trustee in 1827 after he died. Those documents do give us a list of his meager holdings though, one wagon and gear, 4 horses, 3 cattle, 12 hogs, 3 feather beds, furniture, 2 bedsteads, all household and kitchen furniture and plantation tools, which he includes in with the land to secure the debt of $560.58. That would have left his wife, Lucy, with absolutely nothing – not even a pan to cook in, let alone anything else. This is the act of a truly desperate man.

However, Lucy never released her dower when he obtained the fateful loan in 1822.

After William’s death, Lucy sued Isaac Medley, the person who purchased William’s land (or debt) for $200 to obtain her 1/3 share of the dower rights and won. Actually, Isaac agreed to allow her the widow’s dower share. We’ll never know of course whether he did that because it was the right thing to do, or because he knew unquestionably that he would lose the suit if it went to trial.

I do know that hard feelings between the Moore and Medley families continued into the 2000s, but no one seems to remember why. As one Moore descendant in Halifax County says, “maybe that explains why the Moores have always disliked the Medleys,” except his language was stronger.

In addition to the actual documents of the lawsuit, we also have a survey showing William’s initial holdings and the portions with the “mansion house” apportioned to Lucy. She held this land free and clear, not as a life estate and it began right across the road from the old Moore Meeting House.

Given that Lucy didn’t sign, I wonder if Lucy even knew that William had used their property as collateral for the 1822 loan.

While this may have, in part, been due to the lingering 1812 tobacco issue, it surely wasn’t entirely due to that. William owed far more than $68 plus interest would have covered. I can’t help but wonder how he came to owe so much money.

The 1824 debt to William Bailey for $100 as a result of a lawsuit would have complicated William’s financial situation further.

The 1824 document is the only signature of William’s that is shaky. Was he simply that upset? He certainly could have been if they just finished in the courtroom and another $100 issue was added to his already insurmountable debt. Was he an old man who saw the writing on the wall and knew that he was sinking?

My heart aches for William. No one wants to be vulnerable and watch everything you’ve worked for your entire life slip beyond your grasp.

No one wants to leave their elderly spouse of 50+ years unable to receive the basics of food and shelter without having to depend on their children.

William’s other signatures really don’t match each other either, although we don’t know why. It’s possible that his only authentic signature in the last few years of his life was the 1824 debt paper because everyone involved knew how legally critical that signature was.

He could have signed with an X and had the signature witnessed, but William was probably too proud to submit to that indignity on top of the debt indignity he was already suffering.

Y DNA

William Moore had several sons, but his Y DNA signature isn’t found through his sons, but from his brother’s descendants, plus a matching genetic signature from a descendant of Thomas who was probably William’s son.

William’s brother, Mackness Moore (c1766-1829) married Sarah Thompson and moved to Grainger County, Tennessee along with the Thompsons and Stubblefields. Mackness had son Richard, who had son Mastin Moore, shown below.

Mastin, William’s great-nephew, seated, is the closest we’ll ever get to seeing a Moore male. He probably resembled William, at least somewhat.

Viewing the Moore Worldwide Y DNA project at Family Tree DNA, we see that the descendants of James Moore are assigned as Group 19.

In addition to the 3 men who descend from James Moore and the one from Thomas Moore, we see another individual whose ancestor was John L. Moore, born in 1866 in Tennessee and married Lillie Whitaker.

John L. Moore’s death certificate shows that he died on September 14, 1932 in Nashville. He was a farmer and his father is given as Jim Moore.

The 1870 census shows John L. Moore, age 4, with brother Samuel, age 2, sister Amanda J. age 15 and brother William C., age 18, with James Moore, 39, and wife Mary, age 25, living in Putnam County, TN. It’s clear that William and Amanda aren’t Mary’s children, but John and Samuel look to be.

In 1880, James and Mary are living in Morgan County, with James working for the railroad. They now have additional children, Frances, 9, Mary, 7, Lydia 4, and James 1. John’s mother has been attributed as Mary Scott, but the delayed birth certificate for the James Moore whose mother was Mary Scott was born on October 2, 1882 in Sparta, White County, unless the James Moore who was in the 1880 census died.

James Moore, the father was born in 1831 in Tennessee. The name James looks quite familiar, of course. We know that Moore men migrated to Grainger County, but we have no idea if James descends from the Grainger group or whether, if we could simply pierce the brick wall of the identity of James’s parents, we might be able to push William Moore’s brick wall right over too.

After waiting 15 years, in 2018 a new Moore match appeared. The match isn’t exact, but a genetic distance of 3 at 67 markers. That man hails from Scotland, although I don’t know where in Scotland and he has yet to answer.

At least we have a Moore match that reaches back in time before James Moore, which answers unspoken questions about his paternal line.

Questions, so many Questions…

As I review William’s life, I’m left with so many questions.

- How did William and apparently his brothers and father avoid the Revolutionary War? If William was born in 1750, he would have been the perfect age to have served between 1775-1780. The Methodists were not pietists. One William Moore swore an oath of allegiance in Pittsylvania County in 1777. This could have been our William, given how close he lived to the county line, but we don’t know.

- Why did William become exempt from taxes in 1797, and was sporadically exempt for 7 of the 12 years we have records for between 1797-1810?

- Why did William stop returning marriage documents in 1797? Was it related to a disability or the fact that he withdrew from the Methodist Conference? If so, that should have been in 1793, unless William didn’t withdraw when O’Kelly did. However, we know that by 1794, William was involved in the formation of the new religion, and that predates the 1797 discontinuance by 3 years.

My guess is a disability of some sort given the exact correlation with the first tax exemption year. However, we know that William was still attending the annual conference in 1805 and marrying people in 1817, according to his deposition, so the source of his disability might have resulted from an accident of some sort as opposed to dementia, strokes or related diseases.

- Why did William allows the overseers of the poor to bind Thomas’s young children to Anderson Moore after Thomas’s death instead of taking them to raise? Was whatever happened to William in 1797 a factor?

- When William left the Methodist Church, did his new denomination have their own ordination practices? If so, did O’Kelly ordain him again? Was he both twice dissenting and twice ordained?

- How was William, or was he related to the Womacks, Stubblefields and Fergusons? DNA matches suggest strongly that either he was descended from the Womack family. Records of all three of those families are intermixed in Prince Edward and Amelia Counties and earlier.

- The name Azariah is very unusual, yet we find Azariah Baily in 1780 as a witness to a deed with Charles Spradling and Edward Henderson, neighbors of both James and William Moore. Azariah Moore was born between 1780 and 1790. Was Azariah Baily related to William Moore or his wife? DNA shows no apparent matches to the Baily family of Halifax County.

- The name Lemuel isn’t common either. We find a Lemuel Ferguson witnessing a deed with William Moore on Sandy Creek in 1793 when Nimrod Ferguson (Farguson) sells land to Hudson Farguson, his son. Nimrod Farguson appears as early as 1771 on a road list with James Moore. There are several DNA matches to descendants of both Nimrod and Isaac Ferguson, born in the early 1700s, but these matches could be a result of other lines. The name Isaac is possibly found in William Moore’s family but Nimrod doesn’t appear in the children of either James or William.

- I know this is impossible to answer, but I’d surely like to know where William is buried. I’m guessing with his father in the Henderson Cemetery located on private land.

The Reverend William Moore, apparently a tenacious man who dissented not once, but twice, still stubbornly guards his secrets some 200 years later.

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on the link to one of the vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- Family Tree DNA

- MyHeritage DNA only

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload

- AncestryDNA

- 23andMe Ancestry

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists for genealogy research

Well done! My “William Moore(s)” are named “John Bayles” (Bales, Baily, Baly, etc., etc.) I have been researching him for more than 20 years and I do think I know which one John the Immigrant was but, there are still all of those others, some related, some not. The greatest mystery is figuring out which John in England was “my John”. Well, it goes on… Then, of course, there is the nagging question as to who his wife Rebecca was but she seems to have become the 4th wife of William Hallet after the death of John. There are records for that but what became of her and where did she come from and why do some descendants get her confused with her daughter of the same name? These mysteries can be agonizing but also “fun” and they keep me digging and with each turn of the spade, more information arises and more mysteries..

“Turn of the spade.” Love it!!

I must apologize to you. I only just today discovered your replies to several of my posts. I had no idea! From now on, I will check WP for those replies and try to do better at paying attention.

I think there is an option to follow replies, but it might be all replies, not just to your comments.

absolutely no problem! I learn from every one of your posts! Karen Crawford Jennings

I’m sure you won’t remember, it’s bees a year or two since I asked you to look into my husbands Ward family who originated in N or S Carolina about 1817 moved thru Tennessee and settled northwest Arkansas where my husbands grandfathers was born in 1852. At least one other of his other maternal lines also migrated same path. Treadaway,

His DNA now shows 1% Native American, but reading explanation, looks like that could also include Canada and South American ancestors. Is there any particular SNP or STR that is particular to Native American that I should look at … as you can tell, I know much about how to use DNA! Do you do research for others for an hourly rate? Karen Crawford Jennings

Hi Karen. I don’t. I refer people to Legacy Tree Genealogists and if you tell them I referred you, you will receive a $50 coupon. https://www.legacytree.com/dnaexplain

Thanks so much!!! Karen

Hi Roberta! I believe that William Moore might be my 6x gr grandfather,,, how would I take a dna test to prove this?

If your surname is Moore, take a Y DNA test. If your surname isn’t Moore, can you find a male Moore from your line who descends from him through all males? Otherwise, you need to take an autosomal test to see if you match his other descendants.

Wow, Roberta! this is an impressive piece of work! I’ll try to follow your guidance to determine which William Crawfords are not my Wm Crawford’s ancestors!

Aah yes, the Methodists. I’m reminded of the many twists and turns of my research into the life of my ancestor, William Routledge, alleged to have been a Wesleyan minister admitted at the 1801 conference in England. I had corroborating evidence that the family were indeed Wesleyan Methodists, but I never could find evidence of William’s ordination. Eventually I gave up looking, but then my interest was tweaked recently when I discovered him and wife, and two toddlers on a list of Methodist immigrants to Nova Scotia in 1774 (available at Ancestry.com). I was gobsmacked because, until then, I was certain that the family’s entire time was spent in East Riding Yorkshire. Evidently, they returned back to Yorkshire within a short period of time because that is where the rest of William and Sarah’s 10 children were born. Thanks to your informative article I now want to know more about their part in Methodism in Canada during the American Revolution, and any possible connections to the “Loyalists” who left the American colonies during war.

You just never know there those ancestor trails are going to lead you! How interesting.

I have been researching the descendants of the surnames you mentioned for a few years, and so far I have a mess. Some names tend to show up as DNA matches, and others are only linked by genealogy research.. The problem is the DNA and surnames show up in several different lines of my and my husband’s family. Possible descendants of these people have surnames that have married our closer cousins. There might be more than one DNA match to a person. When I get DNA matches, many do not give any information about their family, and do not respond to emails, so I am left to wonder. Researching Moore and other common names is perilous, as you pointed out very well. Your research on Rev. William Moore may help me with research on several of the surnames you mentioned who lived in that area. Thank you for all the work you have done, and for writing about it with clear explanations. It is very appreciated!

Yes, I have the same issues with DNA matches.

Later on, some of my dissenting religious families that moved to Indiana and on to Iowa joined the Church of Christ. Some became Baptists. I had wondered about the Church of Christ.

Where might I find records of dissenting religious families in Virginia?

There is no list. I found what I found in the court records and then the Methodist Church.

“There were at least five, count ‘em, five, William Moores in Halifax County, Virginia in the late 1700s, and at least two James Moores. Of course, every William and James had children named William and James, and Thomas too. Oh yea, there were Thomas Moores in Halifax connected to the Williams and James. By 1800, we had another 3 “disconnected” Williams, probably sons of the other Moore men.

I was pulling my hair out.”

LOL! Right now, I am working on a case from New Netherland and British Colonial America, and I need to identify the records pertaining to the probable father out of all the records pertaining to up to a dozen men of the same name (first name and patronymic), several of whom seem to be from the same generation (no baptismal records in North America since they are immigrants), and others probably from the next generation based on when they got married (whose baptismal records is also in Europe). However, since men have their whole life to procreate, it might even be wrong to assume their age based on their date of marriage.

Several of these men left very few records, which makes it difficult to identify them, and thereby exclude them as candidates. Several others left a huge amount of records since they were well-connected, high-profile individuals.

Since the focus of my research is one of those high-profile individuals, is there a rule of thumb on when to consider these less-documented, and probably less influential individuals as unlikely candidates in situation X or Y? What I’m thinking, right now, is that I’ll have to consider many events as “probable events in the life of Mr. Main Focus” perhaps simply because there isn’t documentation to say that records 1-2-3 DIDN’T pertain to these lower-profile individuals of the same name. A number of these records mention other high-profile individuals who are known associates of my main focus, so it looks like it’s Mr. Main Focus. What is reasonable doubt, and what isn’t? When is it scientifically justifiable to say, for instance, highly probable as opposed to just probable, if you want to be rigorous, but still not unreasonably doubtful in your interpretation of the records?

I have seen that genealogists researching the lower-profile men of the same name attached records to their ancestor, even though these records can be proven to belong to somebody else if one digs deep enough. The biggest problem occurs with the records where the only identifier is that member of the FAN club, who could arguably also know two or three of these men with the same name. One baptismal record is especially tricky for that reason.

Pingback: Lucy Moore (c 1754-1832), Minister’s Wife – 52 Ancestors #246 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

I am most interested in your William Moore who accepted a slave in Payment of his wife’s share of her father’s estate – James Hill. My ancestor William Moore appears to e married to Sarah Hill. Can you share more details or sources? Thanks for any help you ay provide.

Norma

Yes. Where is your William Moore from?

I’m e-mailing you a summary that I put together. If you have a Moore male to Y DNA test, please do.

Thanks again for a great article. You may already know but it was during this time the Methodist ruled to end their part in slavery. I had once thought that it was why my first American father John Follis, who also lived on Birches Creek, sold his three slaves. However, I have yet to find anything to connect him to the Methodist Church although his son and grandsons would be. It was more likely he was with our John Creel and Thomas Dodson, the Baptist pastors. I’m curious now after reading this. Again, thanks for sharing. I love the pictures. I saw Mt. Vernon Baptist Church when I was there in 2014, hoping there was a connection.

Just wanted to let you know that I have some more information on Rev. Moore related to his ministry. I am doing some research on the early Methodist church in America for a book. Your information has been very, very helpful – clearing up a question or two. You Rock!!

Anyway, email me at pmcguireumc@aol.com and I will summarize what I have found for you.

Thank you immensely!

Pingback: Lucy Moore (c 1754-1832), Spunky Plaintiff – 52 Ancestors #248 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: James Moore (c1720-c1798), Life on the Second Fork of Birches Creek, 52 Ancestors #250 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

The early Methodists did not have ordained ministers, because up to 1784, they were members of the Church of England, and used Anglican ordained minsters. They did have local or lay ministers, who preached and did circuit riding – but did not officially offer sacraments. These lay Minsters were licensed or certified. The 1779 self-ordination by the southern minsters is what led to the formation of the Methodist Church in the USA in 1784. Could these minsters of 1779 have ordination papers? Sure, many print shops could have fulfilled that kind of request. I am sure these minsters thought their ordination was legal in the eyes of God.

Pingback: Mary Rice (c 1723 – c 1778/81), Are You Really Your Sister? – 52 Ancestors #251 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

I descend from Thomas Moore who was born May, 1782 in Halifax, Virginia. He died in 1845 in Elbert, Georgia. He married Judith Booth circa 1799 in Georgia.. Does anyone have any idea who his father was? I have done the Y DNA test and I am happy to share my results. My email is alexandermoore42@yahoo.com, if anyone can help me.. Thanks so much!

I would love to know if you match my group of Moores. Recently two Moore project were merged into one so I’m not sure how they are grouped now. Do you match anyone with the James Moore born around 1720 group?

Hey there!

My apologies, I know it’s been a year since I posted here. But, I just saw your reply and wanted to follow up. I went back and looked at the Moore family DNA group and I saw my ancestor, Thomas Moore is in a group by himself! I have zero matches at the 67-marker level.. I am in a group by myself and it has recommended that I upgrade to Big-Y-700.