Thomas Day. Even his name brings a chill to my bones…now that I know who he is and what he very probably did to Elizabeth, his wife. Thomas and Elizabeth Day are my 7 times great grandparents. Thomas very probably murdered Elizabeth, in 1699, in their home in Essex County, Virginia.

Thomas Day was probably born about 1651, probably in old, now extinct, Rappahannock County, Virginia and died in 1706 in Essex County, VA. Old Rappahannock County was incorporated into Essex County when it was formed in 1692. If Thomas was not the original immigrant, then his parents likely were, as Jamestown was only settled in 1607 – so we aren’t far from the original settlers.

I recently found these early immigrants in the book “Lists of Emigrants to America 1600-1700”. Thomas’s father has been reported to be another Thomas, but I have never found any documentation for that. If anyone has more information about these lines, in particular, the immigrant Thomas, I’d be very grateful.

The names Day and Daye are impossible to tell apart so I’m listing them all.

- Anthony – age 22 to VA on the Ship Pauli July 1635

- Dorothy – age 17 same as above

- Hanna – servant age 20 to New England on the Ship Elizabeth and Ann May 1635

- James – Commander of ship Thomas and Sara, Sept. 18, 1679

- (3 similar entries for James above)

- John – age 16 to Bermados (Bermuda or Barbados?) Sept 1635 ship Dors

- John – living in VA Feb. 16, 1623 at College Land

- John and his wife – in 1620 on the ship London Merchant – also on the Hogg Doland muster

- John – in the Sumner Islands

- Robert – age 30, April 3, 1635 to New England on the ship Hopewell

- Samuel – listed in index but could not find entry

- Thomas – listed as “Poor” in Barbados

- Thomas Dayes – age 20, 1634 to Barbados

- Mary – age 28, see Robert

- Richard – age 32, to VA May 1635 ship Plaine Joan

- Robert – age 30, April 1634 to Ipswich on the ship Elizabeth

In 1676, Thomas Day married widow Dorothy Young Hudson in Old Rappahannock County, Virginia. Dorothy was the daughter of Robert and Anne Parry Young. Dorothy (born circa 1646, died before 1698) was the widow of Edward Hudson with whom she had three children: Serania/Lurana, Anne, and William. The following is reported to be the marriage contract between Thomas Day and Dorothy Young Hudson:

“Know all men by these presents that I Thomas Day of Rappa Planter doe upon consideration of a marriage with Dorothy Hudson as alsoe for and in consideration of a horse received of the said Dorothy hereby engage myselfe my heirs and assigns to buy a mare filly of a yeare old the same to be bought within two years and what female increase comes of the said mare to be equally divided between Laurana, Anne and William Hudson and Mary Bartlet and I do hereby engage that the first two calfes that fall [ends.]”

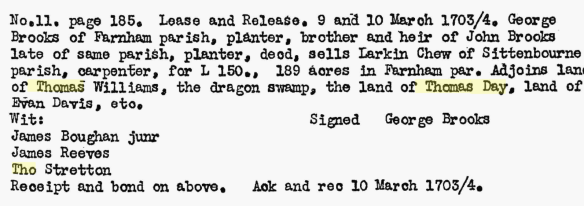

Early records show that Thomas Day purchased land from William Hudson and wife Rebecca Woodnut Hudson located in Essex County, Virginia in 1687. He also purchased 189 acres in Essex County, Virginia from a John Brookes in 1693.

This 1703 transaction gives us at least a waterway in Essex County.

We find his land on the map below, in the area in gray, in essence between the two orange balloons in Essex County, on Dragon Swamp, also known as Dragon Run. This was an area where the Indians used to hide.

The Mitchell map, below, drawn in 1751 shows Dragon Swamp.

We know very little about Thomas Day, but we do know what was going on in the region where he lived.

In 1676, the same year that Thomas Day married Dorothy Hudson, Bacon’s Rebellion broke out in this part of Virginia, in fact, Virginia had its own mini-Civil war. While this sounds “cute,” it was anything but. Everyone had to choose sides.

In 1676, Nathaniel Bacon and many settlers rebelled against the governor, attacking Native Americans, and eventually burning Jamestown.

You either declared “for” the renegades, or they ransacked your home and maybe worse.

In part, Bacon’s Rebellion was fueled by Bacon’s compulsive, unwielding position that all Indians needed to be attacked and killed. In addition, the landed class did not like the fact that the governor had signed into law sweeping reforms passed by the House of Burgesses allowing unlanded freemen the right to vote. Did that apply to Thomas Day?

After passage of these laws, Bacon arrived with 500 followers in Jamestown to demand a commission to lead militia against the Native Americans. The governor, however, refused to yield to the pressure. When Bacon had his men take aim at Berkeley, he responded by “baring his breast” to Bacon and told Bacon to shoot him himself. Seeing that the Governor would not be moved, Bacon then had his men take aim at the assembled burgesses, who quickly granted Bacon his commission. Bacon had earlier been promised a commission before he retired to his estate if he could only be on “good” behavior for two weeks. While Bacon was at Jamestown with his small army, eight colonists were killed on the frontier in Henrico County (where he marched from) due to a lack of manpower on the frontier.

On July 30, 1676, Bacon and his army issued the “Declaration of the People of Virginia“. The declaration criticized Berkeley’s administration in detail. It accused him of levying unfair taxes, appointing friends to high positions, and failing to protect frontier settlers from Indian attack.

Bacon and his men attacked the innocent (and friendly) Pamunkey Indians. The tribe had remained allies of the English throughout other Native American raids. They were supplying warriors to aid the English when Bacon took power.

When Governor Sir William Berkeley refused to march against the Native Americans, farmers gathered around at the report of a new raiding party. Nathaniel Bacon arrived with a quantity of brandy; after it was distributed, he was elected leader. Against Berkeley’s orders, the group struck south until they came to the Occaneechi tribe. After getting the Occaneechi to attack the Susquehannock, Bacon and his men followed by slaughtering most of the men, women, and children at the village.

After months of conflict, Bacon’s forces, numbering 300-500 men, moved to Jamestown. They burned the colonial capital to the ground on September 19, 1676, pictured in the 18th century drawing, below. Outnumbered, Berkeley retreated across the river.

Eventually, the governor prevailed, but that was not the sure and certain outcome for much of the rebellion and probably would not have been had Bacon not died.

Before an English naval squadron could arrive to aid Berkeley and his forces, Bacon died from dysentery on October 26, 1676. John Ingram took over leadership of the rebellion, but many followers drifted away. The Rebellion did not last long after that. Berkeley launched a series of successful amphibious attacks across the Chesapeake Bay and defeated the rebels. His forces defeated the small pockets of insurgents spread across the Tidewater. Thomas Grantham, a Captain of a ship cruising the York River, used cunning and force to disarm the rebels. He tricked his way into the garrison of the rebellion, and promised to pardon everyone involved once they got back onto the ship. However, once they were safely ensconced in the hold, he trained the ship’s guns on them, and disarmed the rebellion. Through various other tactics, the other rebel garrisons were likewise overcome

The 71-year-old governor Berkeley returned to the burned capital and a looted home at the end of January 1677. His wife described Green Spring in a letter to her cousin:

“It looked like one of those the boys pull down at Shrovetide, and was almost as much to repair as if it had been new to build, and no sign that ever there had been a fence around it…”

Bacon’s wealthy landowning followers returned their loyalty to the Virginia Government after Bacon’s death. Governor Berkeley returned to power. He seized the property of several rebels for the colony and executed 23 men by hanging, including the former governor of the Albemarle Sound colony, William Drummond.

After an investigative committee returned its report to King Charles II, Berkeley was relieved of the governorship, and recalled to England. “The fear of civil war among whites frightened Virginia’s ruling elite, who took steps to consolidate power and improve their image: for example, restoration of property qualifications for voting, reducing taxes and adoption of a more aggressive Indian policy.” Charles II was reported to have commented, “That old fool has put to death more people in that naked country than I did here for the murder of my father.” No record of the king’s comments have been found; the origin of the story appears to have been colonial myth that arose at least 30 years after the events.

Indentured servants both black and white joined the frontier rebellion. Seeing them united in a cause alarmed the ruling class. Historians believe the rebellion hastened the hardening of racial lines associated with slavery, as a way for planters and the colony to control some of the poor.

We don’t know what Thomas Day did or his sentiments during Bacon’s Rebellion, but there wasn’t such a thing in that time and place as someone who was uncommitted or ambivalent. You were on one side or the other, and if you didn’t decide for yourself, someone would be deciding on your behalf.

Before 1698, Thomas married second to Elizabeth. We don’t know Elizabeth’s surname, nor do we know when she was born, nor where, although probably in Virginia. We don’t know exactly when she married Thomas Day, but it was sometime after 1687 and before 1698. She had one child before her death in early 1699. It’s her death that we know the most about. Elizabeth was murdered, horrifically murdered, beaten to death, very likely at the hands of her husband, Thomas Day. And we only discovered this terrible fact, some 314 years after it happened. Talk about a well-kept family secret. You would think if any oral history would survive, this juicy piece would. Maybe the family was ashamed and didn’t speak of it. Or maybe it was just too painful.

Elizabeth Mary Angelica Day, believed to be the only child of Thomas and Elizabeth, per his will, born between 1687-1698 (probably closer to the 1698 date), married George Shepherd about 1725. They lived in Spotsylvania County, Virginia. Their son, Robert would marry Sarah Rash and they would settle in Wilkes County, beginning the Shepherd line in western NC.

Indicted for Murder

Thomas Day was indicted for the murder of his wife, Elizabeth, in 1699. Exactly what transpired concerning this event is not completely clear – but the depositions from the neighbors are pretty damning.

According to recorded testimony, it appears that a neighbor, Mary Hodges, visited the Day home and found Elizabeth Day’s dead body lying on a bed. She had been severely beaten, and Thomas Day also had wounds on his face. Thomas Day said his wife died about two hours before sunrise, but he did not know what had happened to her. He told Hodges that his facial wounds resulted from hitting his head over a “potrack.” A jury indicted Day for the murder of his wife, but he was acquitted. A man named John Smith was later found guilty of Elizabeth’s murder and was executed.

Nothing is recorded concerning Smith’s relation to the Day’s or his motive–only that he was found guilty and executed (presumably hanged).

Testimony concerning this case follows:

Essex Co., VA Deeds and Wills BK 10, Part 1, 1699-1702; page 31A; 10 Feb 1699;

The deposition of Judith Davy aged 27 years or thereabout, being Examd and swoorn saith that upon ye 9th of this instant and going to ye house of Tho. Days of Ffarnham in ye Essex County at ye request of Mary Hodge, her neighbour and seeing ye Days wife lying dead upon ye bed in a most horrod and barborey mannor all gored in blood this depo. asked him how his wife cam to be in that condition who mad answer he know not. Thy Depot. further asked him if he and his wife had been quarrelling who replyed that he and his wife had not had an angry word this many a day also they Depot further asked him if anybody had been lately thoto who answered nither did he see anhbody also they Depot. asked him how he burned his eyes who replyed again ye pott rack and being asked a little while after by this depot. how he hurt himself he answered the Lord Knows, I know not and this Depot. saith furthor that ye Sd. Tho. Day had then and at the same time his face and eyes most greviously bruised and further saith not.

Judith Davy

Sworne before me ye Day and yeare above written; Rich’d. Covington

The deposition of Elizabeth Aeres, aged thirty-eight years or thereabout, being Examined and Sworne saith that upon the ninth of this instant that going to the house of Tho. Daye of Ffarnham parrish in Essex County at the request of Mary Hodge, he neighbour and seeing the sd. Days wife lying dead upon the bed in a most horrod and barboriy mannor all Gored in Blood thy deponent asked him how his wife came to lie in that condition who made answer he knew not this Depo’t further asked him if he and his wife had been quarrelling who replyed that he and his wife had not had an angry word this many day also thy depont. further asked him if anybody had been lately there who answered no neither did he see anybody also this dDepont. asked him how he hurt his Eyes who replyed against the potrack and being asked a little while after by thy depont’ how he hurt himself he answered the Lord knows I know not and thy Depont saith further if the sd. Thomas Daye had then at the same time his face and eyes most greviously brused with severall wound and bruses upon his head and further saith not.

Elizabeth Aeres

Sworn before me the day and yeare above written By me Rich’d Covington in ye Place of A Coroner

The Deposition of Mary Hodges aged seaventy five yeares or thereabouts being Examined and Sworne saith that upon the ninth of this Instant coming from the house of Mr. Tho. Covingtons and going to Tho. Days of Ffarnham Parish in Essex County seeing the sd. Day setting upon a counch by the fire seemed melancholy asked him how he did who answered he did not know his face and eyes being most greviously brused he presently after tould me that his wife was dead. Your Depot asked him how she came to die who presently replyed she died about two houres before day of morning. Your depot further asked him how his face came to be in that condition who tould me he cut it against the potrack that was over the fire upon which I went to the woman, his wife as she lay on the bed and found her dead your depont. seeing her lying in a most horrod and barborous manor all gored in blood upon….Your depont. took Days wife by one of her shoose which was upon her foot and found her legg to be somewhat limber and the sd. Day requesting her to strip her dead body I told him I may not able of myself to perform it and further told him I would goe for more assistance and call of Judith Davy my daughter in law and Elizabeth Aeres which accordingly I did and ye depont. further saith not.

Mary Hodges

Sworn before me the day and yeare above written. Rich’d Covington in Place of Coronor.

The Inquisition

An Inquisition….taken at ye house of Thomas Dayes in Ffarnham Parish in Essex County ye 10 day of February in ye yeare 1699 before me. Rich’d Covington one of his Majesties Justices of ye Peace for ye County of Essex upon view of the body of Elizabeth day ye wife of Thomas Day….then and there lying dead and ye Jurors being good and lawfull men and Sworne to trye and inquire in ye behalfe of our Sovereigne Lord & King how and in what manner ye Eliza Day came by her death and they upon their oath say that ye Elizabeth Day was much beaten and bruised with both her eyes exstreem black with many other bruses on her face and bruise on her right eare and a hole underneath ye smae eare and we of the juror say..ye cause of ye sd. Eliza Days death and wee of ye Jurors further say that Tho. Day at ye same time was much brused and beaten having both his Eyes Extreemly brused and black several cuts in his head and further upon his Examination would not confess anything how Elizabeth his wife came by them blows and wounds now how he came to be soo beaten himself so we Jurors say that in ye parish and county aforsd and on the eight or ninth of this instant to wit: in ye dwelling house of ye sd. Tho. Day that ye Sd. Eliza. Day was barbarously murdered and by all manner of Circumstances we can find or gather that ye aforesaid Thom. Day is Guilty of ye murdering ye said Elizabeth Day. In Reffereance to ye Same I Rich’d Covington as afforsd togeather with the jurory aforsd: have put our hands and seales ye day and date above written.

Richard Covington in ye Place of Coronor

Sam. Farry, Tho. Ewell, Henry Perkins, Richd. Taylor, Tho. Crants, Tho. Johnsone, Tho. Greene, Wm. Price, Sam. Coates, John Brooks, Tho. Cooper, Henry Geare, Jeffrey Dyer, Tho. Williamson February 10, 1699.

Thomas Day of Essex Co., VA was charged with murdering his wife Elizabeth Day. Surprisingly, he was acquitted in the Aprill Generall Court 1700. I wish desperately that we had those detailed court notes.

Subsequently, John Smith was found guilty of murdering Elizabeth Day and was executed. October Generall Court 1700.

I’m not lawyer, but I’m going to play prosecutor. Questioning might have gone something like this, based on the information from the depositions and inquisition:

Q – Thomas Day, were you in the house all night the night your wife died.

A – Yes.

Q – Did you know she was dead?

A – Yes.

Q – When did she die?

A – Two hours before sunrise.

Q – How did she die?

A – I don’t know.

Q – Who killed her?

A – I don’t know.

Q – You were in the house and someone murdered your wife by beating her to death, and you don’t know who was there?

A – No.

Q – How did your wife come to be “lying dead upon ye bed in a most horrod and barborey mannor all gored in blood?”

A – I don’t know.

Q – Why was your face so bruised? How did that happen?

A – I hit my head over a potrack.

Q – Your face and eyes were terribly bruised and you did that by hitting your head on a potrack?

A – Lord knows.

Q – What did you do after your wife died?

A – Sat by the fireplace.

Q – So someone killed your wife while you were at home, but you don’t know who. You didn’t come to her assistance and defend her. You didn’t call anyone or go for help. You knew she was dead, but simply sat by the fireplace until your neighbor came to your house. You changed your story about how your face was wounded and bruised from hitting your head on the potrack to “Lord knows.” Gentleman of the jury (ladies couldn’t serve on juries at that time)…..I submit to you that Thomas Day killed his wife, Elizabeth, by brutally beating her to death and watched as she lay dying in a pool of her own blood. What other explanation for his condition and behavior can there possibly be?

However, today’s prosecutor would have an easier job, or the defense attorney one….because we would have DNA evidence. It would be impossible for someone to brutally beat Elizabeth in the fashion described without leaving some of their DNA on her. She obviously fought back and would have likely had the murderer’s blood on her body and their skin under her fingernails.

So today, DNA would have convicted Thomas or removed all doubt, one way or the other. I wish I had a time machine.

Thomas Day’s Death

Thomas Day didn’t live long himself. He was ill when he made his will. It’s unclear who his daughter lived with after his wife’s death and after his death as well. It’s presumed that he had only the one child because no other children are known or mentioned in the will.

Thomas Day died between December 5, 1705 (the date of his will) and February 11, 1706 (when his will was probated), ironicly, possibly 7 years to the day after his wife’s death. At the writing of his will, an ailing Thomas Day had placed himself and his daughter Elizabeth (still a minor) in the care of John Fargason.

The will of Thomas Day from “Fleets Colonial Abstracts” – Essex County, VA Vol 29, page 81, No 12, page 181

“To all to who these presents shall come Greting know yee that I thomas Day of the parish of South Farnham in the County of Essex in Virginia being in a sickly weake and low condition and noe(ways) waies Capable to tke care of, or provide for myself and that little Estate it hath pleased God to bestow upon me (it chiefly lying in Perishable Creatures) have and by these presents doe Bargain Sell Bind and firmly make over unto Jn’o Fargason of the parish and County aforsaid planter all and singular my said Estate”, etc. In consideration Fargason “to maintain and keep me the said Day During my naturall life with sufficient accomodation of victuals Cloathes washing and lodging and give to Eliza a Mary Angillica Day my Daughter when she arrive to the age of Eighteen or when married one Cowe and Calfe.”

5 Dec 1705 signed Tho x Day Wit: John Fargason Wm. aylett Adam Denning Ack and rec 11 Feb 1705/6

On additional piece of information we obtain about Thomas is that he lived in Farnham Parish in Essex County.

When the North Farnham Parish Register opens (1663-1814), there was no such Parish. It was simply Farnham Parish and covered both sides of the Rappahannock River in Old Rappahannock County, Virginia. In 1684 Farnham Parish was subdivided into North Farnham Parish and the Rappahannock River as the natural boundary. Then, in 1692 Old Rappahannock County was abolished and became the parent of two new counties, South Farnham Parish fell into Essex County and North Farnham Parish Fell into Richmond County.

In Essex County, South Farnham was simply called Farnham Parish. The first church was built in 1737, long after Thomas Day was dead. Bishop Meade refers to an earlier church there as “Piscataway.” Given Elizabeth’s demise, I find it hard to believe that Thomas attended church any more often than was required by law, at that time.

There are no Day(e) entries in the parish register.

We don’t know where Thomas Day is buried, but I’d hazard a guess that it’s not in the churchyard.

Reflecting

I can’t even begin to imagine how or why Thomas Day was acquitted of his wife’s murder. Looking at the depositions, some 300+ years removed, it appears obvious and nearly conclusive that Thomas murdered Elizabeth. Perhaps research into the life and social standing of Thomas Day might reveal more information and shed light on this situation. Records in the Virginia archives might contain more information as well, although there are no chancery suits.

I find it extremely hard to believe that Thomas did not murder his wife. In fact, how could he NOT have been the murderer, given the circumstances? The description of her wounds, the severity and the continuous beating that had to have occurred in order to inflict those grave wounds would have been unlikely to have been inflicted by someone simply wanting to get her out of the way, like for a robbery. Those are wounds of passion, of anger, and it looks like she put up a fight as well. Thomas had obviously been in a fight as his own face and eyes were bruised, with wounds, according to the indictment. This was a crime of passion. Added to that was the fact that Thomas’s wife had died in the night, and he had not sought assistance from anyone. He was found sitting by the fireplace. If he had found her bloody and beaten, he would have gone for help, but he didn’t. Instead, he watched her die and left her lying on the bed in a pool of her own blood for the neighbor to find in the morning, stating that he didn’t know what happened.

Even if Thomas didn’t directly murder Elizabeth, meaning that a stranger broke in, beat them both, killed Elizabeth but not Thomas, and left the house – Thomas still has some culpability for Elizabeth’s death, since he was clearly conscious and knew when she died, according to what he told 3 separate witnesses. So he wasn’t asleep or unaware, yet he did nothing before she died to try to help her. He clearly knew she was badly injured. Had she survived, she surely would have named him as the person who beat her. Nor was Thomas distraught by her death. He wasn’t found sobbing at her bedside.

So Thomas Day not only killed his wife, he is also responsible for the death of John Smith in 1700 who was hung for Elizabeth’s murder. In essence, if Thomas murdered Elizabeth, he murdered John Smith too. I hope that if John Smith’s family finds out that he was hung in Essex County, Virginia, as a murdered, that they google and find this article.

All of this makes me wonder how his first wife died, assuming that his first marriage ended with the wife’s death.

Chances are that Thomas and Elizabeth’s child, Elizabeth Mary Angelica Day never knew her mother, for whom she was named, or was too small to remember her. She may well have been in the house when her father murdered her mother, and depending on her age at the time, might well remember the event. She could also have been an infant. If she was, then she likely didn’t remember either her mother or her father very well as he died just a few years later, in 1706, as an invalid. Somehow Thomas’s death not long after Elizabeth’s seems like karmic justice. If he did in fact murder Elizabeth, we can wish him a long and miserable death, dreading and fearing his own passing, knowing that he would face sure and certain retribution for his actions in the court of ultimate truth. There is no other justice to be wrought for Elizabeth – none.

As she grew up, Elizabeth the daughter would have known that her mother was murdered, and even though her father was acquitted, she surely would have known about the circumstances surrounding her mother’s death. When she married George Shepherd about 1727, she may have been all too happy to leave the area and settle in Spotsylvania County, striking out for a new location where she could leave the past behind. In essence, she had been raised an orphan under the storm cloud of her mother’s terrible death and her father’s inferred guilt.

How her mother’s death must have haunted her. To lose your mother is bad enough, but to know she died horrifically, and possibly, or probably, at the hands of your own father, is an unspeakable burden for anyone, let alone a child. How could she embrace the memory of her father who took her mother from her? In essence, she lost both parents when her mother died, and her father again at his own death. Of course, it’s also possible that whoever raised her shielded her from the truth, and perhaps that is why this story never descended through the family. Maybe Elizabeth never knew the extent of her father’s involvement. Let’s hope not, for her sake and let’s hope Thomas wasn’t abusive to Elizabeth as well.

Of course, since there were no known sons of Thomas Day, we can’t retrieve his Y DNA. We don’t know who his parents were, so we don’t know if he had male siblings, or who they were, so that avenue is closed to us as well.

There is a Day DNA project, but unfortunately, it is not hosted at Family Tree DNA and the site doesn’t provide any ancestral information, so it’s entirely useless in terms of trying to find a specific line or even a geographic location. The genealogy site it connects to is no longer being maintained, so a double strike-out.

I think this is one ancestor I’m just as happy to leave among the dead. I pray that I didn’t inherit very much DNA from him, or any traits. From now on, I’ll blame my temper on him. He has to be good for something. As my mother used to say, if all else fails, you can always serve as a bad example.

The research about the murder of Elizabeth Day compiled by a cousin at http://www.danielprophecy.com/daye.html.

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- Family Tree DNA

- MyHeritage DNA only

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload

- AncestryDNA

- 23andMe Ancestry

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists for genealogy research

Pingback: Unwelcome Discoveries and Light at the End of the Tunnel, 52 Ancestors #156 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Thankfulness Recipe | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

I’d love to read details of the trial & conviction of John Smith. I’m curious how there was evidence to convict him and how he did not have an alibi.

You and me both.

This is a fascinating article which I found when I was searching for my Hudson ancestors. Also, Roberta, I think you and I are related through the Estes line. Just a comment. 🙂

Roberta, I descend from Elizabeth May Angelick DAY. As I research this episode, I can’t get my head around the relationships of Thomas DAY and his wives (I found the danielprohecy detail on archives.org.)

Dorothy YOUNG had three children by Edward HUDSON in the span of 4 years. Then when she marries Thomas DAY. They are married for nearly 25 years but have no children. This seems unlikely.

Then Thomas DAY marries Elizabeth ~1698 and has Elizabeth May Angelick DAY within just a year.

It’s a quick turnaround from 25 years no children, to less than a year newly married with a child.

Consider this theory:

1.) We have no death date for Dorothy YOUNG.

2.) We have no marriage date for Elizabeth

3.) familysearch has comments that Dorothy YOUNG may have been known as Elizabeth.

4.) Dorothy YOUNG was fertile.

5.) Thomas DAY never in 25 years appears to have fathered a child. So he appears sterile.

Theory:

Elizabeth is, in fact, Dorothy Elizabeth YOUNG.

She is married to Thomas DAY for 25 years and never has a child due to him being sterile.

Suddenly in 1698 she is pregnant. Proving she has been unfaithful.

This could be motive for Thomas DAY to murder his wife of 25 years.

We’re at the edge or what atDNA might be able to prove, but might matches between Elizabeth May Angelick DAY descendants and Edward HUDSON descendants at least prove whether or not Elizabeth was also Dorothy YOUNG?

Thanks for reading. Love you work.