We know very little about Elisabetha Mehlheimer. Were it not for her daughter’s children’s christening records, we wouldn’t know anything at all.

What do we know? Elisabetha was born probably about 1800, judging from the fact that she had her daughter, Barbara (possibly Maria Barbara), on December 12, 1823. Elisabetha could have been born as early as 1780 or as late as 1810.

We know that Elisabetha lived in Goppsmannbuhl in 1823, because that is where Barbara was born.

We know Elisabetha was dead by 1851.

In the christening record of her daughters second child, born in 1851, Elisabetha is listed as “the former day laborer in Goppsmannsbuhl,” which indicates she is deceased.

We know she was a day laborer. What was a day laborer?

From FamilySearch, we learn the following:

The social hierarchy of a village was determined by the size of farmland and personal property. People with little or no property found themselves at the bottom on the social ranking. These were the sons and daughters of farmers who were not entitled to inherit the farm. The number of people in such predicament grew steadily after the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). They had to work as day laborers or seasonal workers and had to be very creative to make ends meet.

Priests during that timeframe wrote of the deplorable conditions in which day laborers lived. Often, they slept on hay in the corner or loft of a peasant’s home. They have few or no belongings, and lived at only a subsistence level. If they did live in a separate “house,” it was often a poorly made shack on the periphery of the village. Their children left home as quickly as possible to work for themselves or to marry.

There was an entire underclass of day laborers, a significant social notch below peasants who tended to live on and work the same homestead generation after generation. Sometimes day laborers were younger children who stood to inherit nothing. Day laborers often moved from place to place, so can be especially difficult to track genealogically.

Wonderful, just wonderful – Germanic cultural gypsies.

Perhaps Barbara Mehlheimer’s status as a servant was a step up from her mother’s status as a day-laborer. No wonder opportunities in America looked so wonderful.

We know Elisabetha was never married.

In that 1851 christening record, Elisabetha’s surname is listed as Mehlheimerin which indicates she never married and she gave her daughter her maiden name. In German naming practices, the “in” is appended to show a maiden name. Since her daughter’s surname was also Mehlheimer, we know that Elisabetha was not married, at least not when she gave birth to Barbara.

Elisabetha’s daughter, Barbara, was an unmarried servant, so it’s not an unlikely stretch that Elisabetha was in the same social structural class.

The only other clue we have to any possible family connection is that the witnesses to the christenings of Barbara’s two children born in Germany were Barbara Krauss of Windeschenlaiback (today probably Windischeschenbach) and Margaretha Kunnath of Berneck.

Barbara Mehlheimer also was not married at the time she gave birth, so it’s likely that these women were related to her and not to the child’s father. They may have been her sisters, aunts or first cousins. Barbara ultimately immigrated to the US, with both children and did marry the father, George Drechsel (Americanized to Drexler.)

The State Archives in Amberg, Germany, found in a record for the administration of the upper Palatinate that Barbara Mehlheimer of Goppmansbuhl am Berg received permission to emigrate with her two illegitimate children, as well as Georg Drechsler from Speichersdorf, on April 18, 1852.

If Barbara’s mother, Elisabetha, had died, Barbara would have had no reason to remain in Germany when opportunity in the US beckoned.

George Drechsel and Barbara Melhheimer were married shortly after their arrival in the US, on the same say George Drechsel applied for US citizenship. They must have been very happy.

According to the Reverend who found these christening records for me in the church in Wirbenz, Germany, Barbara and George probably had to immigrate to be allowed to marry. He commented on how brave this young couple must have been. In Germany, a young man had to prove he could support his family before he was allowed to marry. Immigrating to America at that time was the social equivalent of eloping. George would have had to work long and hard enough to save enough for both his and her passage, and those of their two children. This was likely their only opportunity, and they seized it, marrying at their first opportunity. Marriage is a right we take for granted today, but one they risked their lives and fortunes to obtain.

This could also explain why Elisabetha never married. Her child’s father couldn’t prove he could support a family.

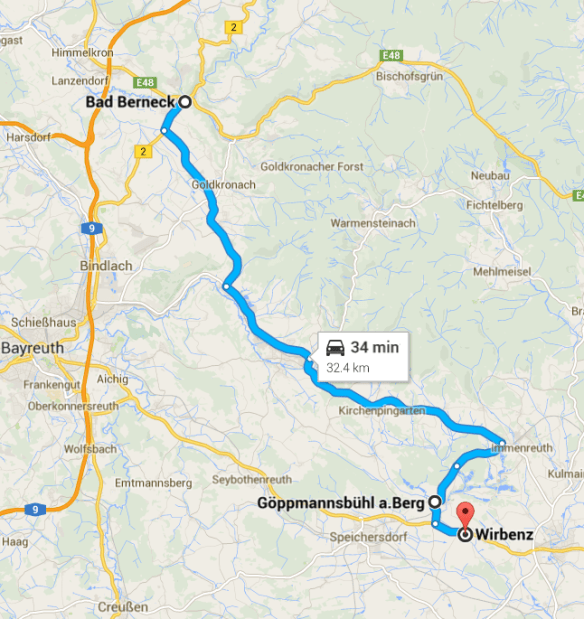

There were no further records pertaining to Elisabetha in the church in Wirbenz where Barbara’s children’s records were found. The church in Wirbenz is the church closest to Goppsmannbuhl.

I was unable to find any record of either Barbara Krauss or Margaretha Kunnath, but I was able to find both locations mentioned. They seem to be about equidistant in either opposite directions from Goppmansbuhl.

You can also see Speichersdorf, located just beneath the Goppmansbuhl label.

Here is the little village of Goppmansbuhl, today, via satellite and thanks to Google Maps.

In the image below, Goppmansbuhl is at the top, and the little village of Wirbenz, about a mile away, is at the lower right. To put things in perspective, the village of Wirbenz is only about 1000 feet from side to side.

Here is the church in Wirbenz where Barbara’s children were baptized.

Photo by grafuse. http://www.panoramio.com/photo/1769873

Did Elisabetha’s view of the church look something like this?

Photo by G. Zapf http://www.panoramio.com/photo/99865838

These are slim pickings for an ancestor – very slim pickings. Perhaps as more records are digitized and transcribed, more information will emerge. We’re dead ended right now, as the church records in Wirbenz don’t provide us with any direction further back in time.

Mitochondrial DNA

The only other thing we know about Elizabetha Mehlheimer is her mitochondrial DNA. Fittingly, it’s just as elusive.

I carry Elisabetha’s mitochondrial DNA, through my mother, and through all females between Elisabetha and me. My children also carry her mitochondrial DNA, but my son’s children carry his wife’s mtDNA and my daughter’s children would continue the line of Elisabetha.

We know that our full haplogroup is J1c2f. We know that haplogroup J, Jasmine, was born in the Middle East some 30,000 to 50,000 years ago. Jasmine’s descendants traveled from the Middle East about the age of the spread of agriculture – and over time, that 4 distinct subgroups, J1, J1c, J1c2 and finally, J1c2f emerged. Dr. Doroh Behar in his paper “A ‘Copernican’ Reassessment of the Human Mitochondrial DNA Tree from its Root,” places the age of J1c2f at about 1900 years plus or minus 3000 years. In reality, that means that anything between relatively recently and about 5000 years ago.

This map shows the grouping in the haplogroup J project of J1c (and subgroup) participants. You can see that there are a few in the Middle East, but very few, so most of J1c and her descendants look to be in Europe today.

My own full sequence matches tell a bit of a different story.

My two exact matches aren’t in Germany, they are in Norway. My matches that are one mutation different are found in Sweden, the Czech Republic and Russia. My two mutation match is found in Sweden.

This is confusing. What happened? What is going on?

In total, I have 9 full sequence matches, although not all of them provided the geographical location of their most distant matrilineal ancestor. One individual does not have e-mail, so I can’t exactly ask them.

Of these matches, 3 are exact, 4 have one mutation difference and 2 have two mutations difference. I’m very curious to know which mutations we don’t share. I have to wonder if there is a mappable pattern to the mutations that would infer sublines. I wrote to my mito-cousins and asked if they would share their mutation information. Two responded, the rest did not. Frustrating. This means that I can’t work from the mutation mapping angle.

Time to find a different approach.

Let’s Go Fishing!

There has to be some type of historic connection between Germany and Norway, or the Scandinavian region. Normally, when dealing with Y DNA, we think of warfare. We look at the history of wars and invasions, because soldiers did leave their DNA sprinkled around the countryside where they visited – if they didn’t outright settle there. But mtDNA is different. Women aren’t soldiers and one can’t just leave mtDNA scattered in quite the same way that Y DNA gets left behind. Mitochondrial DNA is passed from the women to all of her children, and is only passed on by the female children. So, generally, where you find the children, you also find the mother – they don’t deposit their DNA and then go back home.

So, let’s poke around and utilize Google and Wiki, our friends. In other words, let’s go fishing and see what we catch.

Bayern aka Bavaria

Bayern, also known as Bavaria, comprises the entire southeast portion of Germany. It borders The Czech Republic, Austria and Switzerland along with 4 other German states. Bavaria is divided into 7 regions. Bavaria is one of the oldest continuously existing states in Europe; it was established as a stem duchy in the year 907.

The Bavarians as a people emerged in a region north of the Alps, originally inhabited by the Celts, which had been part of the Roman provinces of Raetia and Noricum.

The Bavarians spoke Old High German but, unlike other Germanic groups, probably did not migrate from elsewhere. Rather, they seem to have coalesced out of other groups left behind by Roman withdrawal late in the 5th century. These peoples may have included the Celtic Boii, some remaining Romans, Marcomanni, Allemanni, Quadi, Thuringians, Goths, Scirians, Rugians, Heruli. The name “Bavarian” (“Baiuvarii”) means “Men of Baia” which may indicate Bohemia, the homeland of the Celtic Boii and later of the Marcomanni. They first appear in written sources circa 520. Saint Boniface completed the people’s conversion to Christianity in the early-8th century. Bavaria was, for the most part, unaffected by the Protestant Reformation that happened centuries later.

Wirbenz, Goppmansbuhl and surrounding areas are located in Upper Franconia whose capital is Bayreuth. Upper Franconia was annexed to Bavaria in 1815 and borders the Czech Republic and the German states of Saxony and Thuringia. With more than 200 independent breweries which brew approximately 1000 different types of beer, Upper Franconia has the world’s highest brewery-density per capita. A special Franconian beer route (Fränkische Brauereistraße) leads along popular breweries.

Bavarians tend to place a great value on food and drink. In addition to their renowned dishes, Bavarians also consume many items of food and drink which are unusual elsewhere in Germany; for example Weißwurst (“white sausage”) or in some instances a variety of entrails. Oh yum…

At folk festivals and in many beer gardens, beer is traditionally served by the litre in a Maß, a glass beer mug that holds exactly one litre.

Bavarians are particularly proud of the traditional Reinheitsgebot, or purity law, initially established by the Duke of Bavaria for the City of Munich in 1487 and the duchy in 1516. According to this law, only three ingredients were allowed in beer: water, barley, and hops. Bavarians are also known as some of the world’s most beer-loving people with an average annual consumption of 170 litres per person, although figures have been declining in recent years.

Ok, so now we know that Bavarians aren’t migrants, but the original people of the region and they not only love beer, they are very good brewmeisters.

Bayern is part of Upper Franconia, so…

Who were the Franconians?

Franconia is named after the Franks, a Germanic tribe who conquered most of Western Europe by the middle of the 8th century. Though one might assume that Franconia was the homeland of the Franks (indeed in German, Franken is used for both modern day Franconians and the historic Franks), this is not the case. Until the 6th century AD, the region of today’s Franconia was probably dominated by Alamanni and Thuringians. After the Frankish triumphs over both tribes around 507 and 529–534, most parts were occupied by the Franks.

Ok, so Franconians could be Alamanni, Thuringians or Franks.

The Frankish Empire (at its greatest extent around the year 800) included most of modern Franconia, which was situated at its easternmost borders. The vast majority of ethnic Franks, divided between Salians and Ripuarians, were confined respectively to the Low Countries, the northeastern tip of modern France and the Rhine river banks all the way down to near the Main and Hesse areas. However, there was a Frankish elite which was dispersed all across the empire, and it is from this elite that Franconia derives its name.

Hmmm, I wonder where else they might have been dispersed to…

Around the 9th century Frankish identity gradually changed from an ethnic identity to a national identity. The original ethnic Franks ceased to be called by others and themselves Franks, whereas certain groups of people who were not Franks but were mostly ruled by Frankish nobility now began to use it as a term to describe their respective land and people. At the beginning of the 10th century a Duchy of Franconia (German Herzogtum Franken) was established within East Francia, which comprised modern Hesse, Palatinate, parts of Baden-Württemberg and most of today’s Franconia. These areas had been dominated and settled by the Burgundians and the Alemanni before being removed and resettled much further south around Switzerland. The vacuum left may have been resettled then by some Frankish nobles with some more or less numerous retainers from their original core area.

A vacuum? I wonder who actually did settle there. This is an opportunity and possibility for how Elisabetha’s mtDNA got to Germany.

While Old Bavaria is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, Franconia is a mixed area. Lower Franconia and the western half of Upper Franconia (Bamberg, Lichtenfels, Kronach) is predominantly Catholic, while most of Middle and the eastern half of Upper Franconia (Bayreuth, Hof, Kulmbach) are predominantly Protestant (Evangelical Church in Germany).

Elisabetha’s records were found in a Protestant church.

Now we know more about this region of Germany, and there does seem to be some opportunity for resettlement here around the year 1000, and we also see that some Franks were settled elsewhere, in particular, the elite. But still, that doesn’t connect us to Scandinavia.

Let’s look at this from the perspective of historical Scandinavia, in particular, the locations where my mtDNA matches are found.

Loten, Norway

There has been traffic from east to west through Løten, throughout all recorded periods of history and archeological evidence supports earlier trade along this route.

When King Christian IV of Denmark prohibited the importation of German beer in the early 17th Century, distillation began in Norway. In 1624, distilled alcohol was prohibited at weddings, and by 1638 King Christian forbade the clergy the right to distill in their own homes. The corn-growing districts of Løten, Vang (the former municipality in Hedmark), and Romedal all became famous for their distilleries.

Within Løten lies the “border” between cultivated farmland and the winderness. It begins with the wheat fields of the lower eastern Norway, continues around and south of lake Mjøsa, and borders the taiga, the boreal coniferous forests that stretches from eastern Norway until Siberia. The moorland Hedmarksvidda lies in the north.

So, Loten was a trade route, and Norway imported beer until in the 1600s. This timeframe would have been during the 30 Years War in Germany. Now that beer connection is quite interesting, because it tells us that trade between the two locations was indeed healthy and prosperous, at least until 1624. And we already know that Bayern was the heart of beer production in Germany.

Let’s look at Christian IV, King of Denmark.

Christian IV – King of Denmark

Christian IV was King of Denmark-Norway from 1588 until his death in 1648.

He was quite interested in the Thirty Years’ War in Germany where his objectives were twofold: first, to obtain control of the great German rivers— the Elbe and the Weser— as a means of securing his dominion of the northern seas; and secondly, to acquire the secularized German Archdiocese of Bremen and Prince-Bishopric of Verden as appanages for his younger sons. He skillfully took advantage of the alarm of the German Protestants after the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, to secure coadjutorship of the See of Bremen for his son Frederick (September 1621). A similar arrangement was reached in November at Verden. Hamburg was also induced to acknowledge the Danish overlordship of Holstein by the compact of Steinburg in July 1621.

Interesting, but this all took place in the northern part of Germany, so probably not relevant to Bavaria which is located in the southwest quadrant of Germany.

Sweden

Sweden, however, was another matter. In 1631, Sweden invaded Bavaria. Over the following months, they decimated Germany, destroying up to 2000 castles, 18,000 villages and 1,500 towns. That’s equivalent to one third of all German settlements. While this was a horrific development, it doesn’t explain how Scandinavian mtDNA might have arrived in Germany. There is no record that the soldiers brought any women with them. It did however, prove extremely disruptive to the region and may have opened the door for new settlers in some locations.

Let’s take a look at the next location where a full sequence match is located.

Inderoy, Norway

The municipality is primarily an agricultural community, but also has some industry.

The municipality is named Inderøy which comes from the Old Norse form of the name: Eynni iðri, meaning is “the inner island”, probably referring to the peninsula which sticks out into the fjord.

During the Middle Ages Inderøy was called Eynni iðri, meaning the inner island, which is still the meaning of the word Inderøy. Saurshaug (now Sakshaug) was an important political centre until the 20th century. In the Middle Ages it was the centre of the county

During the late Middle Ages and until the breakup of the union between Sweden and Norway Inderøy was the seat of the Governor, Judge, and Tax Collector of Nordre Trondhjems amt, thus it was the county capital of what now is known as Nord-Trøndelag. The Trondhjems, shown below in red, is an area that abuts Sweden and divides Norway in half, north to south. It was important prior to and in the Viking age, but was almost entirely depopulated during the 1300s. The Sami people and others repopulated this region over the next two centuries. All of my Scandinavian matches, except one, are in proximity to this region.

Just as this article was ready to go to press, I received another full sequence match and it is also found in this region, in Nesna, just above the red area, in the fjords, on an island. This is just beneath the Arctic Circle.

We know that haplogroup J1c2f is not Sami, so this is not the source of our ancestors.

Let’s take a look at the areas in Sweden where my matches are found.

Strand, Strom, Sweden (Stronsund)

Strand is a very small village in Sweden whose claim to fame is that it has the largest population of black bears.

Laxsjo, where my second Swedish match’s ancestors are located is too small to even be called a village. Both are located in Jämtland, which was originally an autonomous peasant republic, its own nation with its own law, currency and parliament. However, Jämtland lacked a public administration and is thus best regarded as an anarchy, in its true meaning.

Jämtland was conquered by Norway in 1178 and stayed Norwegian for over 450 years until it was ceded to Sweden in 1645. The province has since been Swedish for roughly 350 years, though the population did not gain Swedish citizenship until 1699.

Historically, socially and politically Jämtland has been a special territory between Norway and Sweden. This in itself is symbolized in the province’s coat of arms where Jämtland, the silver moose, is threatened from the east and from the west. During the unrest period in Jämtland’s history (1563–1677) it shifted alignment between the two states no less than 13 times. These historical and cultural bonds to Trøndelag and Härjedalen have expressed themselves in the name Øst-Trøndelag, in addition to the fact that the Jamts historically never considered themselves to be Swedish Norrlanders.

Jämtland’s name derives from its inhabitants, the Jamts. The name can be traced back to Europe’s northernmost runestone, the Frösö Runestone from the 11th century. The root of Jamt (Old West Norse: jamti), and thus Jämtland, derives from the Proto-Germanic word stem emat- meaning persistent, efficient, enduring and hardworking.

Aha, so the work Jamtland has a Germanic origin.

A Jamtish Neolithic culture emerged during late Roman Iron Age (about the year 400) in Storsjöbygden, although the hunter-gatherers had come in contact with this lifestyle long before they settled down themselves. Since the hunts were rich and successful in Jämtland, it took a long time before a change occurred.

During the Viking age, the settlement in the province grew. This confirms the sagas written by Snorri Sturluson, where he narrates about the Vikings who fled from Harald Fairhair and Norway in about the year 900 and took residence in Jämtland, just like many Norwegians at the same time fled and colonized Iceland.

This makes me wonder if some of them fled into Germany as well.

Religiously the Jamts had abandoned the indigenous Germanic tribal religion in favour of the Norse faith. Aha, so apparently the Jamts themselves were descendants of Germanic tribes.

As the population continued to grow, the Jamts established an Thing (assembly), just like other Germanic tribes. Jamtamót, the assembly of Jamtland, came into existence shortly after the world’s oldest parliament, the Icelandic Althing, which was instituted in 930 CE.

Norse religion is a subset of Germanic paganism, which was practiced in the lands inhabited by the Germanic tribes across most of Northern and Central Europe.

Knowledge of Norse religion is mostly drawn from the results of archaeological field work, etymology and early written materials.

The literary sources that reference Norse paganism were written after the religion had declined and Christianity had taken hold, so it wasn’t painted in a positive way. The vast majority of this came from 13th century Iceland, where Christianity had taken longest to gain hold because of its remote location.

Many other ideographic and iconographic motifs which may portray the religious beliefs of the Pre-Viking and Viking Norse are depicted on runestones, which were usually erected as markers or memorial stones. These memorial stones usually were not placed in proximity to a body, and many times there is an epitaph written in runes to memorialize a deceased relative. This practice continued well into the process of Christianization. Most, but not all of the runestones are found in Sweden. Many runestones tell of the demise of an individual in England, probably on raids.

Like most pre-modern peoples, Norse society was divided into several classes and the early Norse practiced slavery in earnest.

Slavery – I wonder if a female slave could have been brought from Germany at some point.

One of the first things Tacitus mentions in his work Germania is that the Germanic people treasure their animals above all else. Tacitus also concludes that the Germanic people found cultivation repulsive. Instead, he states, the Germanic people devote themselves to food and sleep and besides that they prefer to remain idle. All of this, to certain extents, applied to Jämtland. When the people of Jämtland settled down they relied mostly on pastoralism. Their animals were the source of wealth and they were therefore loved by their owners.

It looks like the original people of this region were Germanic. However, my closest matches aren’t in Germany, where Elisabetha was found, but in Scandinavia.

Did the Vikings later raid and perhaps settle in the Bayern region of Germany?

The Vikings

The Vikings seem to be everyplace in Europe – and they were – so long as there were rivers. This part of Germany seems to have escaped most of the Viking’s wrath – so it’s unlikely that the mtDNA in Germany is a result of a Viking excursion.

Conversely, it’s certainly possible that a Viking took a shine to one of his prisoners and took a nice German girl as a slave or wife – and back to Scandinavia with him.

It appears the Vikings are an un likely migration source relative to Bavaria/Bayern/Franconia.

So, if the Scandinavians were Germanic people, who were the Germanic peoples?

Germanic Peoples

The Germanic peoples (also called Teutonic, Suebian or Gothic in older literature) are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group of Northern European origin, identified by their use of the Germanic languages which diversified out of Proto-Germanic starting during the Pre-Roman Iron Age.

The term “Germanic” originated in classical times, when groups of tribes were referred to using this term by Roman authors. For them, the term was not necessarily based upon language, but rather referred to tribal groups and alliances who were considered less civilized, and more physically hardened, than the Celtic Gauls living in the region of modern France. Tribes referred to as Germanic in that period lived generally to the north and east of the Gauls.

In modern times the term occasionally has been used to refer to ethnic groups who speak a Germanic language and claim ancestral and cultural connections to ancient Germanic people. Within this context, modern Germanic peoples include the Norwegians, Swedes, Danes, Icelanders, Germans, Austrians, English, Dutch, Afrikaners, Flemish, Frisians and others.

This confirms that Scandinavians are considered Germanic.

Prior to the Middle Ages, Germanic peoples followed what is now referred to as Germanic paganism: “a system of interlocking and closely interrelated religious worldviews and practices rather than as one indivisible religion” and as such consisted of “individual worshippers, family traditions and regional cults within a broadly consistent framework. It was polytheistic in nature, with some underlying similarities to other Indo-Germanic traditions.

Many of the deities found in Germanic paganism appeared under similar names across the Germanic peoples, most notably the god known to the Germans as Wodan or Wotan, to the Anglo-Saxons as Woden, and to the Norse as Óðinn, as well as the god Thor – known to the Germans as Donar, to the Anglo-Saxons as Þunor and to the Norse as Þórr.

While the Germanic peoples were slowly converted to Christianity by varying means, many elements of the pre-Christian culture and indigenous beliefs remained firmly in place after the conversion process, particularly in the more rural and distant regions.

In Scandinavia, Germanic paganism continued to dominate until the 11th century in the form of Norse paganism, when it was gradually replaced by Christianity.

Gamla Uppsala, the center of Norse worship in Sweden, with three “royal” mounds representing the three Gods, Thor, Odin and Feyr, is shown below.

Below, the same mounds are shown about 1700.

Towards the end of the 3rd millennium BC, Proto-Indo-European speaking Battle-Axe peoples migrated to Norway bringing domesticated horses, agriculture, cattle and wheel technology to the region.

During the Viking age, Harald Fairhair unified the Norse petty kingdoms after being victorious at the The Battle of Hafrsfjord in the 880s. Two centuries of Viking expansion tapered off following the decline of Norse paganism with the adoption of Christianity in the 11th century. During The Black Death, approximately 60% of the population died and in 1397 Norway entered a union with Denmark.

This may be our answer, but was there back immigration into Germany? Exact matches should indicate a common ancestor in a time frame closer than 5000 years ago, according to the haplogroup age estimates of Dr. Behar.

Norway and The Netherlands

During the 17th and 18th centuries, many Norwegians emigrated to the Netherlands, particularly Amsterdam. The Netherlands was the second most popular destination for Norwegian emigrants after Denmark.

Loosely estimated, some 10% of the population may have emigrated, in a period when the entire Norwegian population consisted of some 800,000 people.

The Norwegians left with the Dutch trade ships that when in Norway traded for timber, hides, herring and stockfish (dried codfish). Young women took employment as maids in Amsterdam.

Barbara Melhleimer was a servant in the mid-1800s where her children were baptized.

Young men took employment as sailors. Large parts of the Dutch merchant fleet and navy came to consist of Norwegians and Danes. They took Dutch names, so no trace of Norwegian names can be found in the Dutch population of today.

The emigration to the Netherlands was so devastating to the homelands that the Danish-Norwegian king issued penalties of death for emigration, but repeatedly had to issue amnesties for those willing to return, announced by posters in the streets of Amsterdam. Increasingly, Dutchmen who search their genealogical roots turn to Norway. Many Norwegians who emigrated to the Netherlands, and often were employed in the Dutch merchant fleet, emigrated further to the many Dutch colonies such as New Amsterdam (New York).

Genetics

According to the paper, “Different Genetic Components in the Norwegian population revealed by the analysis of mtDNA and Y Chromosome Polymorphisms” by Passarino (2002), both mtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms showed a noticeable genetic affinity between the Norwegian population and other ethnic groups in Northern and Central Europe, particularly with the Germans. This is due to a history of at least a thousand years of large-scale migration both in and out of Norway. Norwegian and Swedish Y and mtDNA is closer to Germans than any other European region. The authors expressed the following opinion relative to haplogroup J.

Haplogroup J, possibly brought to Europe by Neolithic farmers coming from the Near East is found at a frequency of 10% in our sample. It has also been reported elsewhere at 7% in Norway. Given its frequency in Northern and Central Europe, it is likely it has been brought by the Germanic migrations to Norway. As previously noted, the distribution of this haplogroup throughout Northern Europe indicates that during the spread of agriculture women moved throughout Europe, crossing group and cultural barriers more so than men. In addition, any asymmetric cultural factors that reduce the effective population size of men relative to women would influence the geographic patterns of mtDNA lineages relative to Y haplotypes.

Positive selection is also a possible influence. The presence of mtDNA haplogroup J in our sample, and elsewhere in Northern Europe shows that its frequency in Norway is even higher than in those areas from where it probably arrived. It would be intriguing, although very speculative, to hypothesise that the climate of Northern Europe may have played a selective pressure where the uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation and the consequent higher production of heat in J individuals may have led to an advantage, as previously suggested for the European groups during the glaciations.

Glory be, hot flashes might have been good for something after all!

In Summary

I compared the raw results in the Passarino paper with my own results. Of the mutations included in that paper, which did not include any coding region mutations, I carry only two, 16069 and 16126. These were reported in every haplogroup J result, where the other 9 mutations were only found in a maximum of two participants each.

It looks very likely, barring new evidence, such as church records that say that Elisabetha Mehlheimer, or her mother, were from Scandinavia and immigrated in the 1600s or 1700s, that we’re going to have to assume the common ancestor of Elisabetha Mehlheimer and my matches lived in Germanic Europe. Given the match below, she may have even lived in Russia, between the Black and Caspian Seas, and her descendants may have migrated to the region now known as Germany, with a subgroup moving further north into Scandinavia.

If this is the case, that means that there have been no mutations in this ancestral line since that migration occurred, at least in the case of the two exact matches in Norway, as long as 5000 years ago.

While this does indeed sound unlikely, I have seen this phenomenon in client’s DNA before.

A second possibility is that someone from Norway returned during the migration of the 1600s and 1700s, adopted a Germany surname, and we are none the wiser today. Given that my only exact matches are in Scandinavia, this seems the most likely scenario.

We may never know for sure. In fact, we’re not likely to know. However, on the KISS scale, where the simplest, easiest, least complex answer is likely to be the right one, the population migration to Norway scenario comes out on top with the remigration in the 1600-1700s second. Both of those events had many opportunities for people to move, and we know for certain that many did. Other scenarios, such as the beer trade, are certainly still a possibility, but on a much smaller scale. Of course, that doesn’t mean they didn’t happen. We can only deal here with history as we know it, possibilities and probabilities.

Elisabetha Mehlheimer’s ancestry and her Scandinavian mitochondrial matches may forever remain shrouded in mystery. However, I at least understand the possibilities. It’s no wonder that those fjords in Norway brought me such joy.

Part of me seems to be there.

Hmmm…I think I’ll go and have one of those nice German beers and ponder the situation.

______________________________________________________________

Disclosure

I receive a small contribution when you click on some of the links to vendors in my articles. This does NOT increase the price you pay but helps me to keep the lights on and this informational blog free for everyone. Please click on the links in the articles or to the vendors below if you are purchasing products or DNA testing.

Thank you so much.

DNA Purchases and Free Transfers

- Family Tree DNA

- MyHeritage DNA only

- MyHeritage DNA plus Health

- MyHeritage FREE DNA file upload

- AncestryDNA

- 23andMe Ancestry

- 23andMe Ancestry Plus Health

- LivingDNA

Genealogy Services

Genealogy Research

- Legacy Tree Genealogists for genealogy research

Being a J1C2, I enjoyed reading this article probably because the migration patterns and terms were familiar to me. Jane Picking born in S. C., USA 1791 is as far back as I have traced my mtDNA strand.

A beautiful essay that makes sense of all those migrations. Thank you.

Agree! also on my family.

FYI, the German word for France is still Frankreich – the realm of the Franks. So the French are really Germans. 🙂

Don’t tell them that. I don’t think they’d like it:)

THANKS Roberta, that’s quite a romp through European history, and a challenging conundrum to figure out. I’m still waiting for my mtDNA results to come back from FTDNA and hope I don’t have such a complex story.

Personally I’m not to sure about the beer trade idea. Germany has a strong beer producing culture all over the country and Bavaria is (mostly) on the wrong side of the European Watershed which would make shipping hard. I would have thought it more-likely that the German beer to Scandinavia came from the cities of the Hanseatic league up north. I wouldn’t dismiss the idea that your mtDNA came to/moved from Scandinavia via warfare. If I understand it correctly most armies had quite large groups of camp followers (the WAGs of the day) see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tross as an example.

Best Wishes

Phil

PS. I think at one point you’ve mixed up your terminology on beer. Beer is fermented, distilling makes the hard stuff (vodka, korn etc)

I enjoyed your article. My grandmother’s aunt Nicolene Johnsson is buried

In the yard of the old church in Inderoy Norway. It is a sublimely

beautiful place. Many years ago I instructed my children to have my

ashes scattered there.

Mark

Roberta, you skipped over the obvious source of mtDNA, which was the 30 Years War. Gustav II Adoph was related to the Polish kings of the time-cousins-he took his army into northern Europe in defense of Protestantism which was under attack from Catholic Germany. His army would have consisted of about equal number soldiers and baggage train, the various trades necessary to keep an army in the field, like blacksmiths, vets, nurses, cooks etc. At least half of that baggage train would have been women.I am sure you have heard of Bertolt Brecht’s play Mother Courage and her Children, which is about that war and that situation. Mother Courage was a subtler from Dalarna in Sweden.

I also have a group of Swedes at genetic distance=0 in my mtDNA matches, with Swedes, Finns and Norwegians, and the odd Russian and Pole at greater distance. My mtDNA haplogroup is K1b2a1. My known distant maternal ancestor was born in Silesia, Gruneberg, in 1803. The only explanation I can find that suits the circumstance is nothing to do with Romans, but a lot to do with Swedish activities in central Europe in the early 17th century. I suspect my maternal ancestor was in Gustav’s baggage train and got left behind, or, quite possibly, when the war was over Sweden held a long piece of the southern Baltic shore-Pomerania etc, and controlled the river mouths which were the keys to inland trade. She may have been living there and fell for some bloke who had come up from the bush to trade wheat or flat pack furniture, and went back down the rivers to Silesia. 200 years later her female descendants left Germany in 1838 as part of an evangelical Lutheran emigration to South Australia.

As for Celtic history, the Romans fought the Gauls who were Celts- Julius Caesar and his ‘history’ of the Gallic wars is interesting, though he was fighting in an environment which was civilised when Rome was a collection of shacks on the Tiber. Celtic Europe stretched from what is now Portugal into the deep dark forests of central Europe along what became the Roman frontier. After Rome had conquered Gaul and Britannia, and established that frontier, the moment it was breached various peoples flooded over the landscape. The Vandals and Visigoths, who some believe hailed from Sweden, and the Franks. The Frankish empire’s most famous king was Charles the Great, Charlemagne, the grandson of Charles Martel, or Charles the Hammer, who defeated Moorish invasions of France at Poitiers. His capital was not Paris but Aachen in what is now Germany, and his empire and its dependencies stretched from the border with Spain east to the Oder river and down the Danube to what is now Serbia, most of what we now call western Europe, and what one might reasonably say was the old Celtic Europe with a few additional bits, mainly in the north.

Actually, I hadn’t heard of Mother Courage, but you can bet I’m searching now. Thank you.

Pingback: Haplogroup Projects | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Tenth Annual Family Tree DNA Conference Wrapup | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: In Anticipation of Ancestry’s Better Mousetrap | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Proving Your Tree | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Mother’s Day – Tracking the Mitochondrial DNA Line | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Visiting Mom at Family Tree DNA | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Giving the Gift of Memories | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: We Match…But Are We Related? | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Barbara Drechsel (1848-1930), The Kirsch House, Turtle Soup and Lace, 52 Ancestors #110 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Ethnicity Testing – A Conundrum | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Barbara Mehlheimer (1823-1906), Floods, Flames and Celebrations, 52 Ancestors #112 | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Concepts – Genetic Distance | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Writing Ancestor Articles in 12 Easy Steps | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Building Your Personal Mitochondrial Tree | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

Pingback: Family Tree DNA Holiday Coupons and Mitochondrial DNA, The Forgotten Test | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy

I know that it has been years since you wrote this, but there is one part of your research you got sort of wrong. The “no documented women in the Swedish army in the 30 year war”.

There were women and children following the army. The wives and families of the soldiers followed their husbands and fathers. They are the ones that cooked, cleaned etc. There is even a proclamation from 1621 that whores are not allowed near the army, but a soldiers wife is welcome.

This link is in swedish, but it might give you something to work with?

http://militarhistoria.se/artiklar/kvinnor-i-krig

Thank you very much for this information.

Pingback: Conferences: Different Flavors – How They Work & What to Expect as an Attendee or Speaker | DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy